New York’s arts scene remains shut down indefinitely—can it evolve and survive?

From theater and dance to comedy and concerts, a world of culture tries to digitally reinvent itself.

New York is a city of secular churches—and for three months the pews have been empty.

Yes, the city is home to famous sanctuaries like Riverside Church, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and Église St-Jean-Baptiste. But more than any other city in the world, New York is known for its thousands of theaters, museums, galleries, studios, concert halls, bars, and hole-in-the-wall performance spaces that create a cultural mecca for both artists and patrons alike.

Sure, Paris has the Louvre. London has the West End. Sydney boasts a world-famous concert hall, and Rio de Janeiro has the Theatro Municipal.

But New York—New York has everything. It’s got Carnegie Hall, and miles of subway platforms where buskers cut their teeth while harboring visions of grander stages. It’s home to the Apollo Theater and the Knitting Factory, the Metropolitan Opera and the Comedy Cellar, Madison Square Garden and the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Plus Rockefeller Center, the Museum of Modern Art, the high school that inspired Fame, New York Fashion Week and the New York Review of Books. It is the nexus and heartbeat of the attention economy, the place that makes and decides what’s cool, what’s news, what’s worth celebrating, what’s worth reading.

But since COVID-19 arrived, many of the elements that define New York have been obliterated. A concrete landscape of omnipresent crowds, fast walking and faster talking, has morphed into a ghost town. The throngs of people who gummed up the thoroughfares of the theater district have been replaced with long stretches of emptiness and eerie quiet. The live drums of BAM’s annual DanceAfrica bacchanal have been silenced. And a newly redesigned MoMA, which would normally be a huge draw as spring and summer temperatures climb, sits empty. The first Monday in May passed without the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual gala celebrating fashion, history, and social climbing.

Before coronavirus forced New Yorkers into their apartments and separated us from each other, millions of people came here in search of community, or, in churchspeak, fellowship. They sought the possibility of transcendence, or at the very least, a good time. That magical, mysterious moment when one wanders out onto the street wondering, How did they do that?, after having congregated with a bunch of strangers bearing witness to a play about abortion set inside a womb, a lavish production of La traviata, or a drag show featuring Arab queens. Broadway alone provided 96,900 jobs and $14.7 billion to the city’s economy in 2019. According to the Mayor's Office of Media and Entertainment, film, TV, theater, music, advertising, publishing, and digital content in New York provide 305,000 jobs, and an annual economic output of $104 billion.

What happens when the very things that bring so many people to New York are forced to shut down? When we’re banned from congregating in sanctuaries of art, drama, dance, comedy, literature, and music, where does the culture go? It adapts to the new reality.

“What is it they like to say?” said comedian Roy Wood Jr., a regular on The Daily Show, which films in Manhattan. “Church isn’t a place—it’s a people.”

And right now, the people—and therefore church—are online.

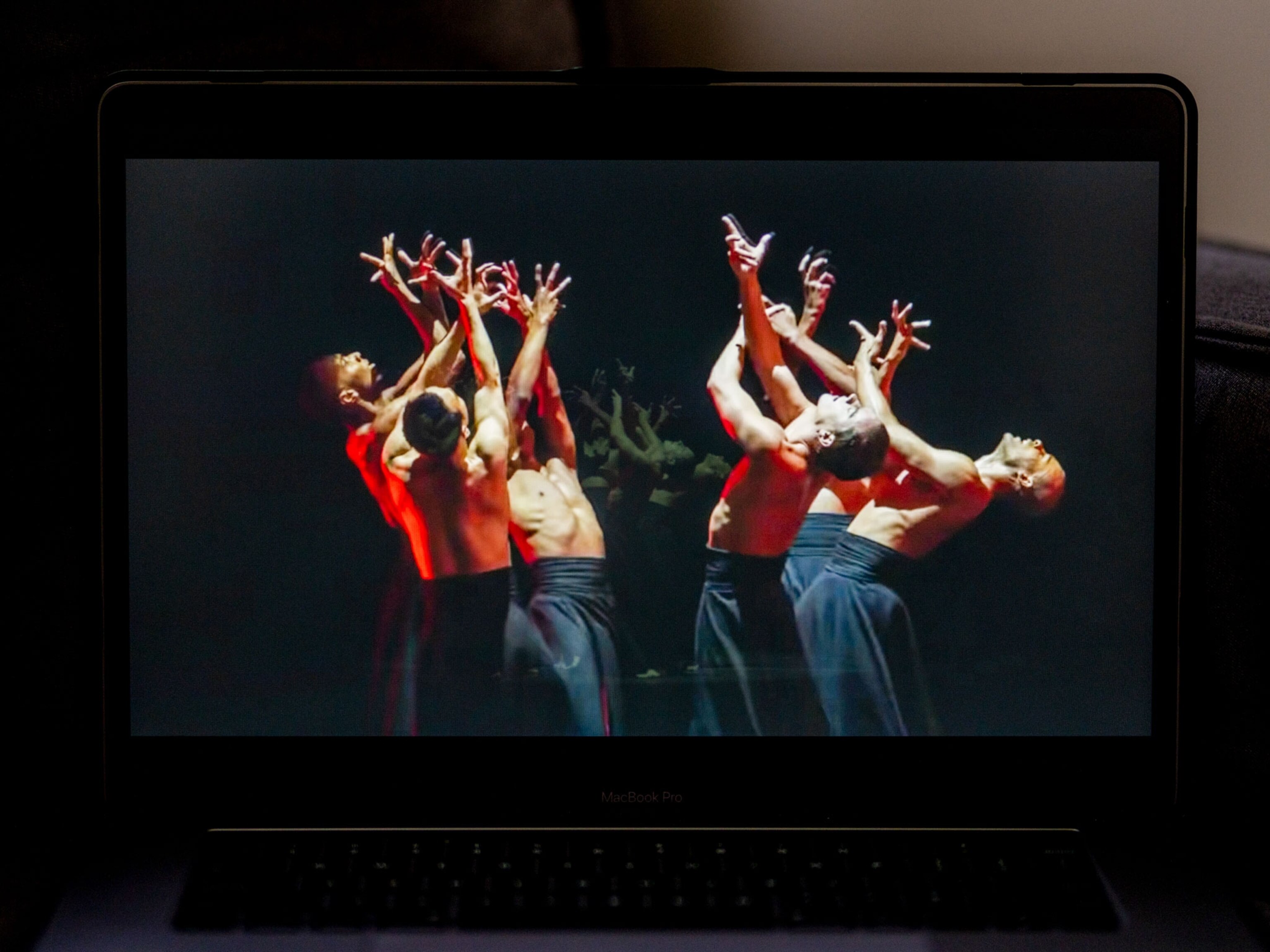

On March 16, five days after New York Mayor Bill de Blasio declared a state of emergency and live productions across the city shuttered, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater published a video on Instagram. It showed company members dancing to a snippet of the spiritual “I Been Buked” from Revelations, Ailey’s most recognizable work, which premiered in 1960 and has been a mainstay of the company’s repertoire ever since.

The dancers stretch their arms heavenward in “unison” from various socially-distanced locales: cramped apartments, a backyard with three curious dogs circling about their dancing human, a small balcony, an alley. The motions aren’t complicated—in fact, before coronavirus, the company used to teach Revelations to the public at Lincoln Center. But even disaggregated from the trappings of professionalism—lights, a vast stage, fine-tuned acoustics that send the bass notes of “‘Buked” rumbling through the soul—Revelations was still Revelations. Ailey famously described African-American cultural heritage as “sometimes sorrowful, sometimes jubilant, but always hopeful,” and every one of those elements was present in the 87 seconds offered in the video, including the hope that someday Revelations would be performed again as Ailey conceptualized it.

Ailey formed his dance company in 1958 to create opportunity for himself and other black dancers who had been excluded from the city’s existing ballet companies. Their initial home, like so many New York residences, was a rental: The 92nd Street Y on the Upper East Side provided a base, and the company embarked on “station-wagon tours” around the country to make money.

Since then, the Ailey company has blossomed from seven dancers to 32, and crisscrosses the globe spreading the gospel of inclusive dance. In the age of coronavirus, it has become a model of evolution and adaptation. Ailey embraced its internet-only existence with Ailey All-Access, its venue for streaming performances. The company’s dancers, artistic director Robert Battle said, have needled him for new choreography as they experiment with the best way to bring the liberation of movement to a population that craves it.

Ailey started the company “on the brink of the civil rights movement at a moment of discord because we didn't have a seat fully at the table,” Battle said. “And so, in a way it already had to do with our DNA being about access, about it being a right, not just a sort of polite thing to do.

“So when you look at where we are today, and our sense of populism—we were kind of suited to be able to address this moment, the lack of accessibility that we’re sort of going through right now because he said it: the best dance comes from the people and should always be delivered back to the people. So I feel that even now he's giving us the guidance of how to meet this moment.”

Is it even possible to bottle that and share it with the world via fiber optic cable and a language of ones and zeroes? Perhaps. It’s early days yet, even though quarantine makes the passage of time feel like an endless abyss of sameness.

There is something inspiring about the way artists have quickly adjusted to the limitations of quarantine, particularly because so much about the creation and consumption of art is communal. Coronavirus has forced everyone to find ways to form connections when physical closeness is now inherently dangerous.

“It’s not the same as standup, but people have gotten so creative,” said comedian Rebecca O’Neal of the online workarounds that have emerged where live performance once ruled. “The urge to be creative and the urge to share doesn’t stop, so people are finding ways to get around it, like water through a maze.”

“Restrictions do force your creativity, you know?” O’Neal said. “Because what else are we gon’ do?”

And so arts organizations such as the Metropolitan Opera, Ailey, La Mama (a respected experimental theater company), Lincoln Center Theater, the Apollo, and the Public Theater (a renowned Off-Broadway theater best known as the birthplace of Hamilton), are trying new things. They are providing some of their past works online, often live-streaming at a set time to mimic a curtain time, rather than simply making theater available on-demand, like television. Those that are financially able are commissioning new work intended for online consumption. Others are retrofitting existing work like Buyer and Cellar, a one-man show from playwright Jonathan Tollins about an actor who works in a fake mall in Barbra Streisand’s basement. Michael Urie performs the entire show in one room, in front of two cameras, like an extended YouTube kvetching session.

“A lot of this new work — that I’ve seen, at least — ends up being this hybrid live film/theatre experience,” Martyna Majok, a Pulitzer-winning playwright whose latest work, Sanctuary City, was shut down before it could even open because of coronavirus, said by email. “You do feel the ‘liveness’ and ‘in-the-momentness’ of some of them — like when there’s technical difficulties, which I often love because I love watching artists create and problem solve in the moment, whether it’s on stage and there’s a prop they accidentally dropped or forgot to bring on, or whether it’s on Zoom and their cat walks into the frame, or they can’t turn on their mic. I’ve found that those kinds of ‘live’ moments can bond an audience to the story and the performer. You feel it ‘happening’ and being made for you. So there’s a little taste of live theatre in them. But you don’t feel it being made with you, necessarily. There isn’t necessarily that energy exchange, that exciting, alive reaching out by performer and response by audience that’s born out of sharing space.”

One of the best examples of this hybrid form is Mama Got A Cough, which has been billed as a short film, but functions more like a Zoom play. Written by Ain’t No Mo’ playwright and actor Jordan E. Cooper, Mama Got A Cough takes place entirely during a Zoom call for one family that’s convened to try to convince their mother to go to the hospital. It was released on YouTube May 18, about two months into New York’s lockdown.

It stars Danielle Brooks and Da’Vine Joy Randolph in a 15-minute slice of socially distanced life, and is filled with easy, pleasurable laughs. Even during a pandemic, brothers and sisters will rib each other’s flighty relationships and drinking habits, and their mother will lay on a thick helping of guilt because her brood doesn’t visit as often as she’d like.

“I think a lot of us are thinking these hybrid live film/theatre experiences are temporary, so if they do let us down, if they can’t replicate that live theatre experience, we comfort ourselves by thinking that someday ‘We’ll be back,’” Majok said. “But what if they’re not? What if we’re not able to assemble in the same way as before for a very long time, if ever? I think we adapt. We’ll always tell stories... in whatever form we’re able.”

It’s not just arts organizations that have had to retool their work—so has television. Take, for example, the late night shows, which are typically hosted by comedians in the company of a studio audience. Small armies of production staffers—camera operators, hair and makeup artists, wardrobe specialists, set designers, editors, graphic designers, writers, directors, lighting designers, audio specialists, musicians, producers and others—would muster in midtown Manhattan to give the shows the glossy finish that broadcasting in high-definition demands. Audiences for The Late Show with Stephen Colbert would congregate outside the Ed Sullivan Theater on Broadway. Similar lines for The Daily Show or The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon would brave snowstorms, rain, or oppressive heat (eliciting that famous New York aroma of urine and rotting garbage)—for a chance to laugh and get a peek at the celebrity guests.

That too, had to evolve.

In the early days of the quarantine, the gleaming aesthetics of expensive sets were supplanted by something more akin to hostage videos: a single camera in a room that had been converted into a makeshift set, with hosts using iPads as teleprompters and their family members as a makeshift crew.

Two months in, there are recognizable tropes of corona productions: the ubiquity of AirPods and “ring light eyes,” especially in episodes of SNL at Home. The green screen is this era's MVP, introducing some visual versatility into productions. Television audiences have witnessed the trial-and-error progression of these setups. Colbert graduated to a high-definition camera parked in his study. Eagle-eyed viewers can see which books surround Seth Myers in his attic. And Desus Nice, one half of Desus & Mero, relies on an ever-changing background of color-coordinated sneakers to keep things visually interesting as he and The Kid Mero chop it up, socially-distanced-style, over Zoom.

“I have a totally newfound appreciation for everybody on the staff, from the [production assistant] that’s like, ‘Hey do you want a water?’ to the camera operator to the lighting, to the P.A. who's holding a little white board under it to get the light balance right,” Mero said.

“If you woulda asked me what a C-stand was two weeks ago, I woulda been like, ‘I don't know what the f--- you talking about!’ Now I know the ‘C’ stands for camera. I built the C-stand by myself—wrong—three times, and I finally got it right and now I’m using it to hang wardrobe because I can’t get the light to stick into it the right way! It just takes so much stuff that I was like, ‘Yo, shout-out to everybody on the Showtime staff times two because there is no job that’s not important.”

O’Neal, who moved from Chicago to New York in 2018 to pursue a career in standup, said comics are adapting to the new, screen-based reality. She’d been doing five standup shows per week prior to the shutdown and was among the first to participate in Comedy Central’s slate of at-home specials. Standup is tricky without an audience since the process of revising a routine relies on seeing which bits get laughs and which do not.

“There’s been a learning curve,” O’Neal said. “Week one, people realized we cannot gather in groups, which is the entire purpose of standup comedy. People started moving to Zoom. They were a little difficult at first because the structure is based on audience interaction and immediate feedback. Is this funny? If no one’s laughing, how do I know? That was interesting the first couple weeks as people compiled best practices and got their s--- together because three weeks later, all of these shows are running great. … A show that’s based in Brooklyn can now book comedians that are in L.A. and Chicago and London, wherever. We’ve never been able to do that.”

Cabaret and drag acts, like those that used to take place at Joe’s Pub or at Hell’s Kitchen staples like Industry and Therapy, face similar challenges. What happens when a queen can’t scurry about in towering heels to collect cash tips? For now, they have migrated to Instagram and Facebook, with performers sharing their Venmo names so that viewers can still tip, even if they can’t stuff a bunch of wrinkled bills into the cleavage of a silicone breast plate.

Bob The Drag Queen, winner of the eighth season of RuPaul’s Drag Race and star of the new HBO docuseries We’re Here, found that performing at home allowed him to pull out costumes too big and unwieldy to take on the road.

“I did a drag show in my living room, which felt really odd ... But I mean, is there anything about this whole situation that doesn't feel odd?” Bob said. “At first I was like, ‘Oh my God this is just a mess! This is sad-looking.’ But then after a while I was like, ‘No it's actually really exciting,’ and I did three shows in one day.

“And a lot of people were telling me they got a chance to see my show and they could never see it before—because they don't have the money, because they can't travel. Going to a drag show is not just the tickets for the show. You have to get to the show. Some people have to take off work, all that extra stuff. Some people have anxiety, some people have physical disabilities.”

The finished products that appear on stages, runways, movie theater and television screens, and gallery walls are the most visible aspects of art and culture in New York. But that work is due in large part to the city’s role as a giant fellowship hall for creative adults. It’s a place where people routinely meet others who become lifelong collaborators and influencers, the way Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lee Quiñones, Keith Haring, Sara Driver, Fab 5 Freddy, Al Diaz, and Jim Jarmusch became part of each other’s orbits in the ‘70s and ‘80s, or how James Baldwin, Anne Spencer, Richard Wright, Lorraine Hansberry, Langston Hughes, Eubie Blake, and Noble Sissle drove the discourse during the Harlem Renaissance, and Dorothy Parker, Alexander Woolcott and Robert Benchley formed the Algonquin Round Table.

“Being in love with New York, it’s like being in love with a musician,” said playwright Celine Song, whose play Endlings, which is set in both South Korea and New York, premiered in February. “Like someone who’s a volatile artist. It's hot when it's hot, it’s mean when it’s mean. It’s brutal sometimes, and then sometimes you're just crying because you love it so much.”

The city was instrumental in the career of Terence Nance, a multidisciplinary artist best known for work such as Random Acts of Flyness and An Oversimplification of Her Beauty.

“You go [to New York] because that’s where all the energy is,” Nance said.

The Dallas native moved here in 2005 to attend graduate school at New York University. He came with his friend, collaborator, and producer James Bartlett. The two, who were roommates in Bed-Stuy at the time, would sell t-shirts at Brooklyn’s African Street Festival, at BAM’s DanceAfrica, and at Union Square as they tried to scratch out a living. Nance made films, but he also busked on the street, designed web sites and business cards, and installed computer RAM to pay the rent.

Nance and Bartlett met Blitz Bazawule, also known as Blitz the Ambassador, a multidisciplinary artist who wrote a 2011 short film called Native Son (not an adaptation of the Richard Wright novel), which Nance directed, after meeting in a chance encounter in the city. Bazawule was selling CDs of his music. Bartlett and Nance liked the cover art. So they traded one of their t-shirts for one of his CDs. A similar run-in on the subway led to a career-long relationship with cinematographer Shawn Peters, who went on to photograph An Oversimplification, Random Acts, and other Nance projects.

“He was like, ‘I just got a camera if you ever want to shoot anything,” Nance said. “I didn’t have a camera at the time. I was like, ‘then let’s do it.’”

“There’s some spirit moving through there that’s assertive of a certain kind of insurgent immigration,” said Nance. “Like I imagine myself here, free and making a lot of money and y’all can’t do nothin’ about it. Even if it’s just a tone, a vibe, and not an economic reality, there’s something in that.”

The people who live and work in New York pride themselves on being unimpressed when they recognize a famous face on the street. It’s where an active film or TV set can temporarily ensnare a pedestrian the way the presidential motorcade becomes a common and unremarked interruption for those who live in Washington, D.C. More than anything, it is a place where the bulk of life takes place outside its undersized, overpriced apartments—well, it was. Until a couple of months ago.

“It’s very weird. Being born and raised here, I’ve never seen New York like this,” Desus said. “I think the best description—I think it was a tweet that said coronavirus turned New York into a suburb in New Jersey. I still have to leave the house to walk my dog. But even on that, like walking around the block, there's no people, there's hardly any traffic sometimes. If you do see someone you have to basically run across the street from them if they don't have a mask on.

“As a New Yorker, for the first time in my life I miss Times Square. I don't think any New Yorker has ever said that.”

For Morgan Jerkins, author of the forthcoming book Wandering in Strange Lands: A Daughter of the Great Migration Reclaims Her Roots, all of these factors influenced her decision to make a home in Harlem. Jerkins, who grew up in southern New Jersey, wanted to immerse herself in the history, culture, and environs of the Harlem Renaissance.

“There was something spiritually purposeful for me to walk around and amongst the avenues and the streets and to know that those who came before me did the same,” Jerkins said. “There is something magical about even tweeting about history in Harlem, or going to a famous church where in the basement there’s the first mental health center in the city for black people. Even Ralph Ellison wrote about it. Stuff like that you can't get in every single place."

The conditions that make New York a sanctuary for artists, patrons, and looky-loos of all stripes, with the spire of the Empire State building functioning as its most recognizable steeple, are also the source of its biggest weakness and strength. As much as the city is a beacon—for freedom, for refuge, for being a place where there’s an existing warren of every type of oddball imaginable—it’s also increasingly divided by income inequality and gentrification.

The gulf between rich and poor here existed long before coronavirus showed up. But it is being exacerbated by the economic destruction that accompanied the pandemic. The artists who are here are debating how their work can help reimagine a post-pandemic New York that expands the ability of struggling artists to remain. (COVID-19 and systemic racism are killing people of color in New York. Will anything change?)

“The cost and therefore the exclusivity that makes it so difficult for lower income artists to break into theatre—or to keep going within it—has been a problem for a long time,” Majok said. “If it now becomes even more costly and even more exclusive, then it kills something vital in our cultural conversation. It kills certain stories and perspectives. A lot of artists I know were already wondering whether they can keep going—to keep writing or making or pursuing—because of how much this city costs just to live in.”

Before coronavirus, Oskar Eustis, who has been the artistic director of the Public Theater since 2005, was trying to give voice to the frustrations of an economically splintered New York while also probing questions of how to reshape democracy. It was evident in the theater’s 2019-2020 programming, which included Luis Alfaro’s Mojada, a story of immigration set in Queens told using the frame of the Greek tragedy of Medea, and Tony Kushner’s A Bright Room Called Day, an illustration of encroaching German totalitarianism on the eve of World War II.

“We aren’t able to do most of the things that make us happy to live in New York. For me, that means I'm holding the platonic ideal of New York in my head, and it may have gotten a little dirty over the last 15 years, and so I'm polishing it,” Eustis said. “I'm sort of reminding myself of What is it that I love about this place? And can I separate that from all of the hassle and stress and difficulties in economic inequality that I struggle with every day?”

Eustis was clear-eyed about what he sees as the serious threats that lie ahead. And just like the younger version of himself who came to New York in 1974 from Minnesota, Eustis believes that theater has a role to play in reshaping society. A jobs program for artists, like the Works Progress Administration, the New Deal program that enabled the documentary photography work of people such as Gordon Parks and Dorothea Lange, is a vital part of the recovery, Eustis said, especially given the months, and possibly years, it will take for audiences to safely convene. Recovery won’t be as simple as reopening theaters and mandating 50 percent occupancy. Such a move would not be financially feasible for most theater companies. Perhaps the answer is a hybrid of streaming revenue and in-person tickets. We just don’t know.

“When we are allowed to do our jobs again, when we are allowed to organize and bring people together in socially intimate ways instead of socially distanced ways, it's going to be our job to very quickly and boldly demonstrate what's so important about the theater, what matters about the theater. And I think we're gonna have to demonstrate it to way more people than believed it before we went down. I think resources are going to be really limited. I think we are going to be in economic trouble, and that one of the things that theater has to do is prove its worth—is demonstrate to people that their lives are better because of theater.”

Now is the time for arts organizations to innovate, artists say—to upend and rethink their business models. They must do the difficult work of orienting themselves around something other than season ticket subscriptions and the tastes of mostly white benefactors. And they must adjust to the reality that gathering together in small, dark, packed rooms will be impossible for months, and possibly well into 2021, unless there’s a coronavirus vaccine, or a rigorous program of testing, contact-tracing, and isolation for those who are infected.

Comedian Wyatt Cenac worried that the city’s culture of creation will be even more gentrified than it was before.

“I think whatever bounce back that happens, that bounce back is probably going to benefit wealthy white people before it starts to benefit everybody else,” Cenac said. “That production of Hello, Dolly! may get back on its feet faster than theater made by a creator of color who’s doing a play that is a thought-provoking examination of race and class and culture. That may struggle and that's where I wonder, as things bounce back, if the bounce back centers a more homogenized view of what we consider art and creativity.

“What are the plays, what are the musicians, what are the comedians, what are the movies, the TV shows that people think of as sure bets? And you know history has told us that people unfortunately have a very racist view of what a sure bet is.”

We know that New York won’t evaporate and neither will art. What we can’t know are the ways the pandemic and its aftereffects will continue to reverberate—how new theatermakers will fold themes of isolation and frustration into work that has yet to be birthed.

New York’s venerable black arts organizations may provide the models for a sustainable future for arts as a whole. Both the Apollo and Alvin Ailey have endured difficult periods before. The Apollo filed for bankruptcy in 1981 but reemerged, its famed stump of the Tree of Hope still providing good juju for performers. The Ailey company nearly went bankrupt in 1989, but now will likely weather coronavirus with the aid of a $50 million endowment. Like Riverside Church, the famed Harlem sanctuary where Rev. Martin Luther King once preached, the dance company is energized by a mission that prioritizes access and is deeply influenced by the civil rights movement. When it comes to imagining a future for New York’s secular houses of worship once coronavirus has passed, someone who leads one of the city’s religious churches has some advice:

“You can’t throw your hands up,” said Riverside’s executive minister Michael Livingston. “You can’t give up. You can’t disappear. You’ve got to keep at it in new ways.”