What the archaeologists of the future will discover about us

Earth is covered with technofossils, or man-made materials, that will last for centuries and maybe even longer.

For less than two dollars, you can purchase a 10-pack of the bestselling pen in the world. Since being introduced in the 1950s, almost 150 billion Bic Cristals have been made. The pen is an exceedingly ordinary item found in most schools and workplaces across the globe. But it harbors a tiny secret. Inside the tip sits a one-millimeter-diameter perfect sphere made of tungsten carbide. It’s this minuscule ball that gives the pen its name and allows it to draw smoothly across a sheet of paper.

The compound tungsten carbide doesn’t exist in nature; it was engineered to be nearly as tough as diamonds and is likely as long-lasting. Highly resistant to wear, heat, impact, and corrosion, tungsten carbide isn’t found just in pens. Trekking poles, guitar slides, armor-piercing shells, and fishing weights all use it too. Millions of years from now, fragments of these items will remain deep in the earth. They will never degrade, serving as a geological time stamp to mark humanity’s presence on the planet.

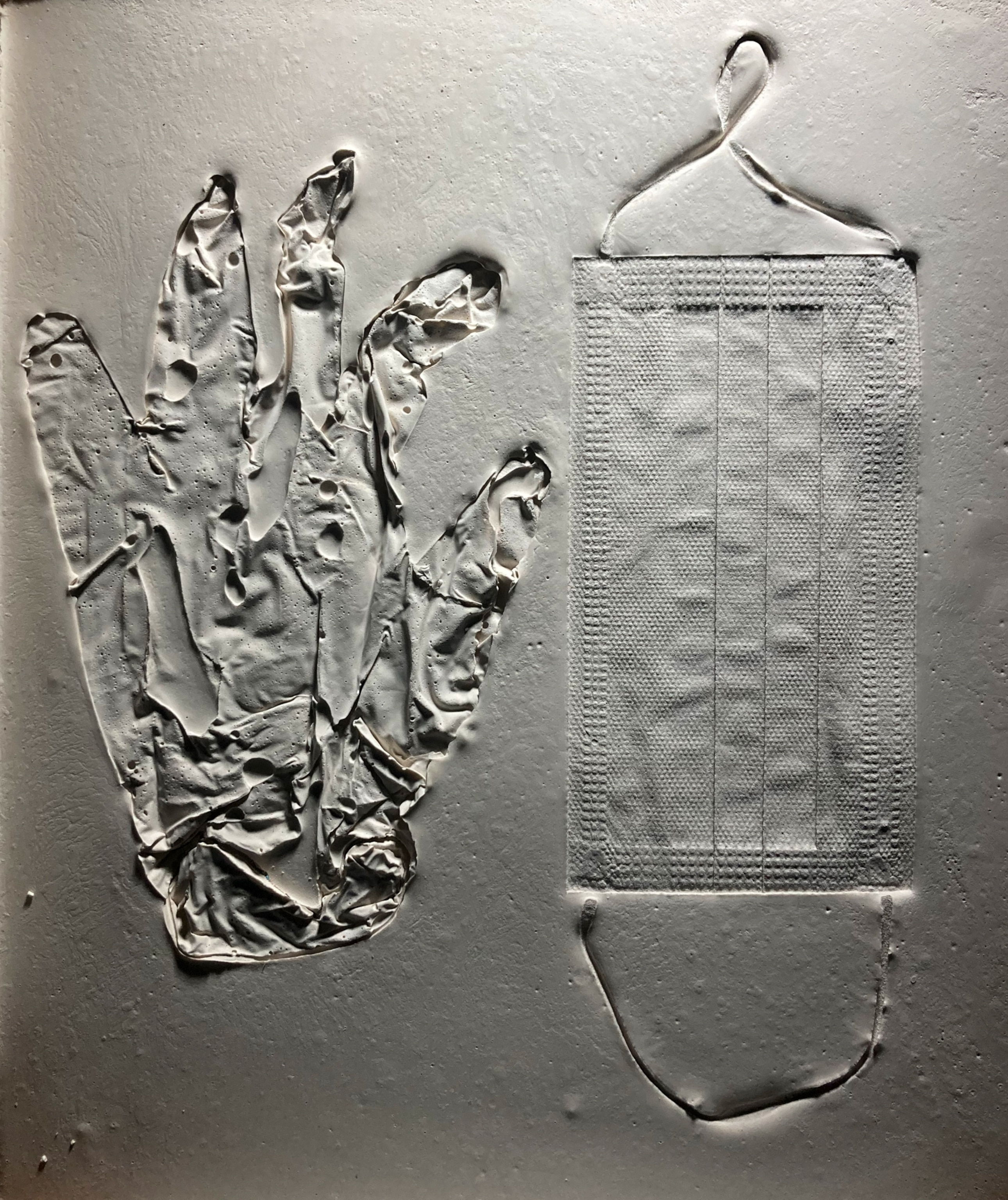

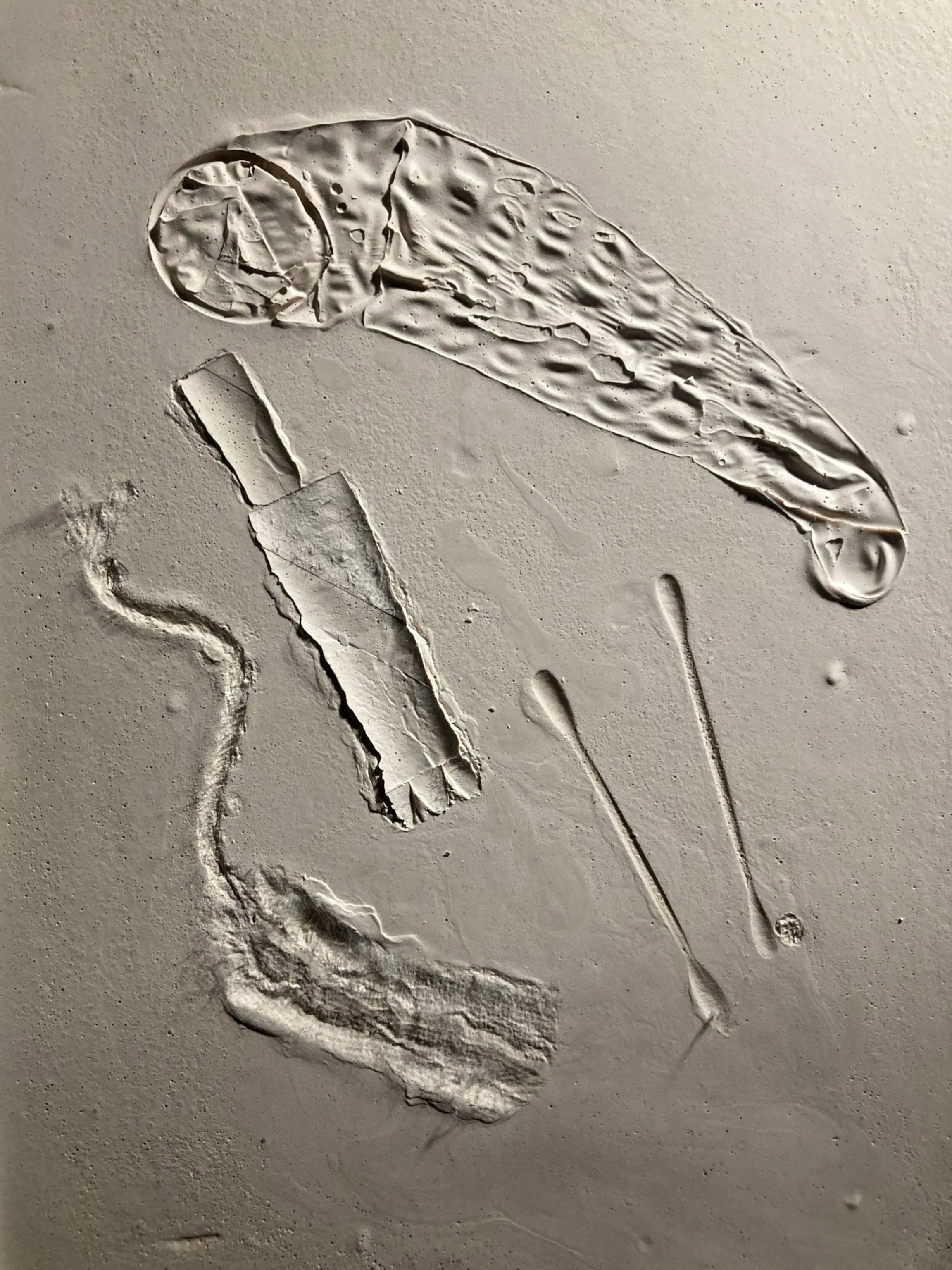

A ballpoint pen is a technofossil, just like a cellphone, its charger, leather shoes, and plastic-laced tea bags. Paleontologist Sarah Gabbott explains that a technofossil is “anything that is man-made, including all the new materials that we’ve made.” Gabbott and geologist Jan Zalasiewicz, colleagues at the University of Leicester, examine technofossils and their impact on Earth in their recent book, Discarded: How Technofossils Will Be Our Ultimate Legacy. Technofossils can be as small as a single radioactive particle, carried on the wind from a testing site, or they can be as large as an entire city, slumping into the sea after decades of climate change. What defines technofossils is their human element. They are unique to our species and terrifically specific to our current time.

In our unprecedented era of human-made stuff, Gabbott and Zalasiewicz ask a provocative question: Where will it all go? “At the heart of this book is a description of the world we’re making, how long it will last, and how long it will be dangerous,” Zalasiewicz says.

Discarded is part paleontological study and part call to arms. In the past 70 years, humanity has manufactured so many objects that our human-made output now outweighs the mass of the living world and, according to some metrics, far surpasses it in terms of diversity. Although some of our stuff will decay—natural-fiber clothing, for instance, has a very small chance of surviving millions of years into the future—many of the things we purchase will not disintegrate, instead entering fossil records of the future.

Our homes could stand for centuries; remnants of our metro tunnels could last for a millennium. Plastic take-out containers won’t be metabolized by bacteria into healthy soil; our chemically complex piles of e-waste will continue to circulate around the globe, leaching lead and arsenic; and nonstick pans may poison living organisms for millions of years. This is what will be left of our century of mass consumption, buried deep in the fossil record, millions of years after those who bought it and built it are gone.

“It’s a very sobering realization,” says Zalasiewicz.

Humanity’s most durable creation

On a geological time span, plastic is vanishingly new.

Since the 1950s, people have produced around nine billion tons of it—and we don’t know how it will degrade. But we’re not flying totally in the dark. “Plastic is just another organic material,” says Gabbott. “Only it’s a man-made organic material.” Formed from the remnants of living matter (decomposed prehistoric organisms), plastic is, like all life on Earth, made primarily of carbon.

To figure out how modern plastic might decay, Gabbott and Zalasiewicz looked at its ancient chemical relative, kerogen, a complex biomacromolecule found in sedimentary rocks, likely created by the compression of organic material. It’s practically indistinguishable from certain modern plastics. Some kerogen has an estimated age of 50 million years, which means its human-made counterpart plastic could last at least that long, under the right circumstances—say, at the bottom of the ocean floor.

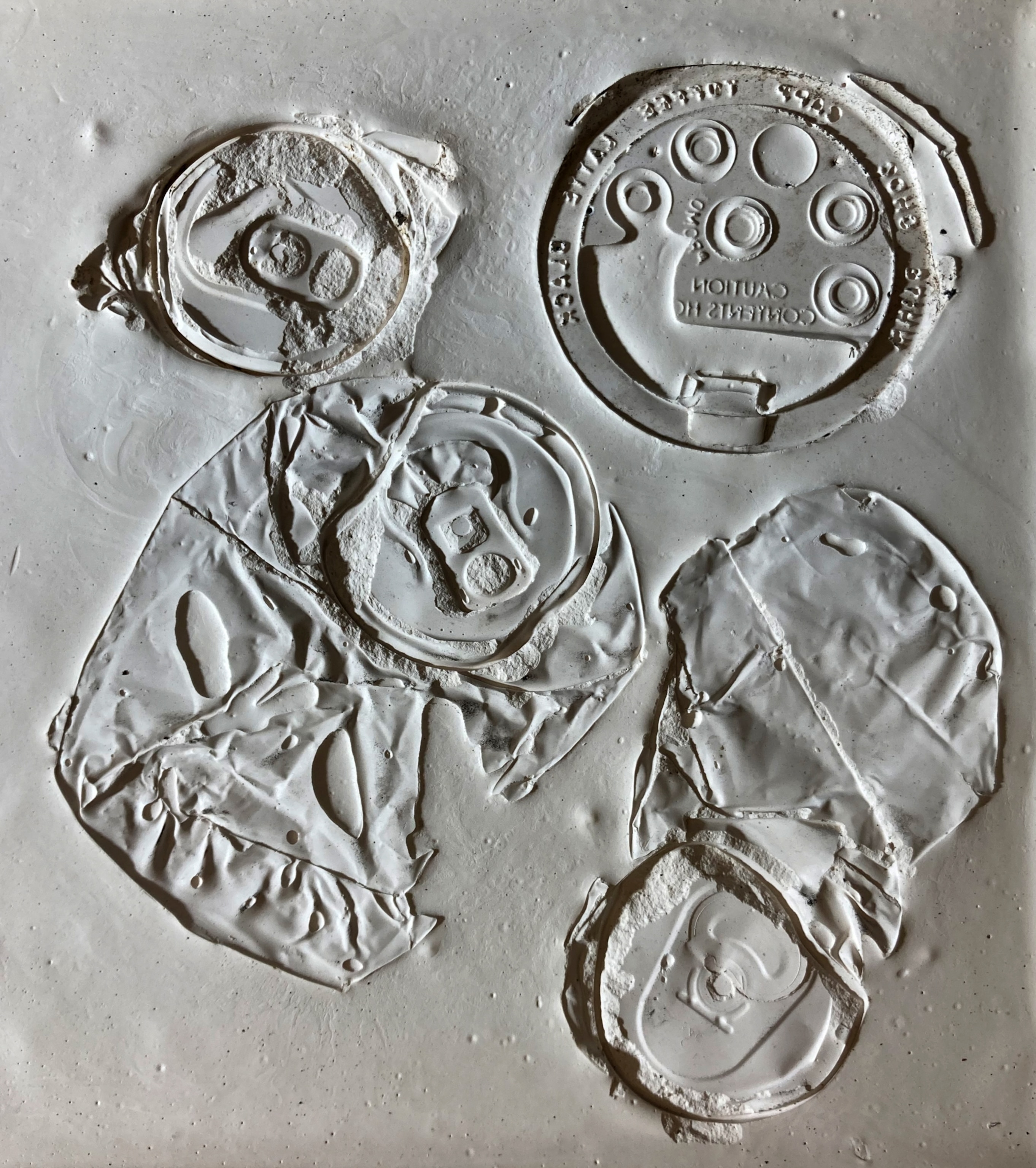

The deep seafloor is littered with plastic like bags, buoys, and bottles. Most of it has broken down and turned into specks of microplastic. These particles come from a variety of unexpected sources. Flakes of latex paint, for example, make up just over half the microplastics in the ocean. While some of this plastic remains on the surface of the water, amassing into huge floating garbage islands, most of it has filtered down to the depths, where it becomes part of the immense plastic stratum that circles our planet.

At the bottom of the ocean, plastics are turned into a “plastiglomerate,” a new type of rock made from plastic fused with small stones and sand or compressed into a black, opaque layer of sediment.

Not all plastics will be transformed over time; some may survive in their present shape long enough for the paleontologists of the future to discover. The densely packed, relatively dry conditions of most landfills ensure that many of the items within won’t degrade. Sandwiched between layers of construction debris, crushed glass bottles, stacks of durable treated papers, and plenty of single-use plastics, even food waste and grass clippings rot at a far slower rate than they would otherwise.

In landfills across the world, our discarded clothes stand a chance of being immortalized in the fossil record. “We make 100 billion garments a year at the moment, which is mind-bending,” says Zalasiewicz. “Sixty percent of those are plastic, and they will survive.”

(Microplastics are in our bodies. How much do they harm us?)

Concrete’s long life

In addition to generating the plastic stratum, humans have developed another geological phenomenon, large enough to encircle the Earth with a two-millimeter-thick shell: concrete. The mix of cement and sand used to pave our sidewalks and parking lots and build our houses may prove as durable as plastic.

Concrete is “the classic rock of modernity,” Zalasiewicz says, and like its naturally forming mineral relatives, concrete is inert. Even when it breaks down, it doesn’t chemically change the surrounding environment. When it comes to toxicity, Zalasiewiczranks concrete as a “smaller problem” than “the plastics, the toxins, and the radioactive stuff.” (He notes that it does take a significant amount of energy to make concrete, so most of the environmental risk happens in the creation, not the degradation.)

Unlike the concrete of antiquity found across the Roman Empire and Syria, modern concrete doesn’t have a long lifespan, but the sheer amount of concrete we’ve used will ensure that some of it remains. From sidewalks to skyscrapers, the main material in most cityscapes is concrete. Within decades of being abandoned, buildings will begin to crumble, but even the pebbles will have to go somewhere. Some will travel along streambeds, making their way slowly to the ocean. And some will likely settle in place, creating a new layer of dense, geologically distinctive aggregate. There they will stay, huge heaps of heavy gray sand, for millions of years.

Not every city will meet this fate. A few of our cultural hubs run the risk of becoming “future mega fossils,” says Zalasiewicz. “Places like New Orleans and Amsterdam will continue to sink,” he says. “Cities that are on deltas are already going down,” adds Gabbott. “And because there’s a lot of sediment to be deposited, they stand a good chance of being fossilized rather than just breaking down into pieces.”

One day, a millennium from now, New Orleans may exist only as a jumble of roadways and buildings, buried deep under layers of compressed silt waiting for archaeologists to discover it.

The legacy of e-waste

A potential quandary for future paleontologists could be the sudden explosion of pure silicon. Although the element makes up 27 percent of the Earth’s crust, silicon on its own is exceedingly rare to find. It’s usually bound up with oxygen to form silicate minerals, like quartz, feldspar, or granite. But in the mid-20th century, metallurgists found a way to extract silicon from a sand made of high-quality, finely ground quartz, paving the way for our digital age.

Silicon chips are tiny but mighty. They power smartphones, laptops, data centers, automated cars, satellites, and spaceships. Compared with other human-made materials, their footprint will be minute. Only around 30,000 tons of silicon is mined each year, far less than the 4.2 billion tons of concrete produced. But silicon chips are widespread, scattered across the surface of the globe, used by billions of people worldwide. Encased in metal and plastic, silicon wafers stand a chance of surviving into the far future.

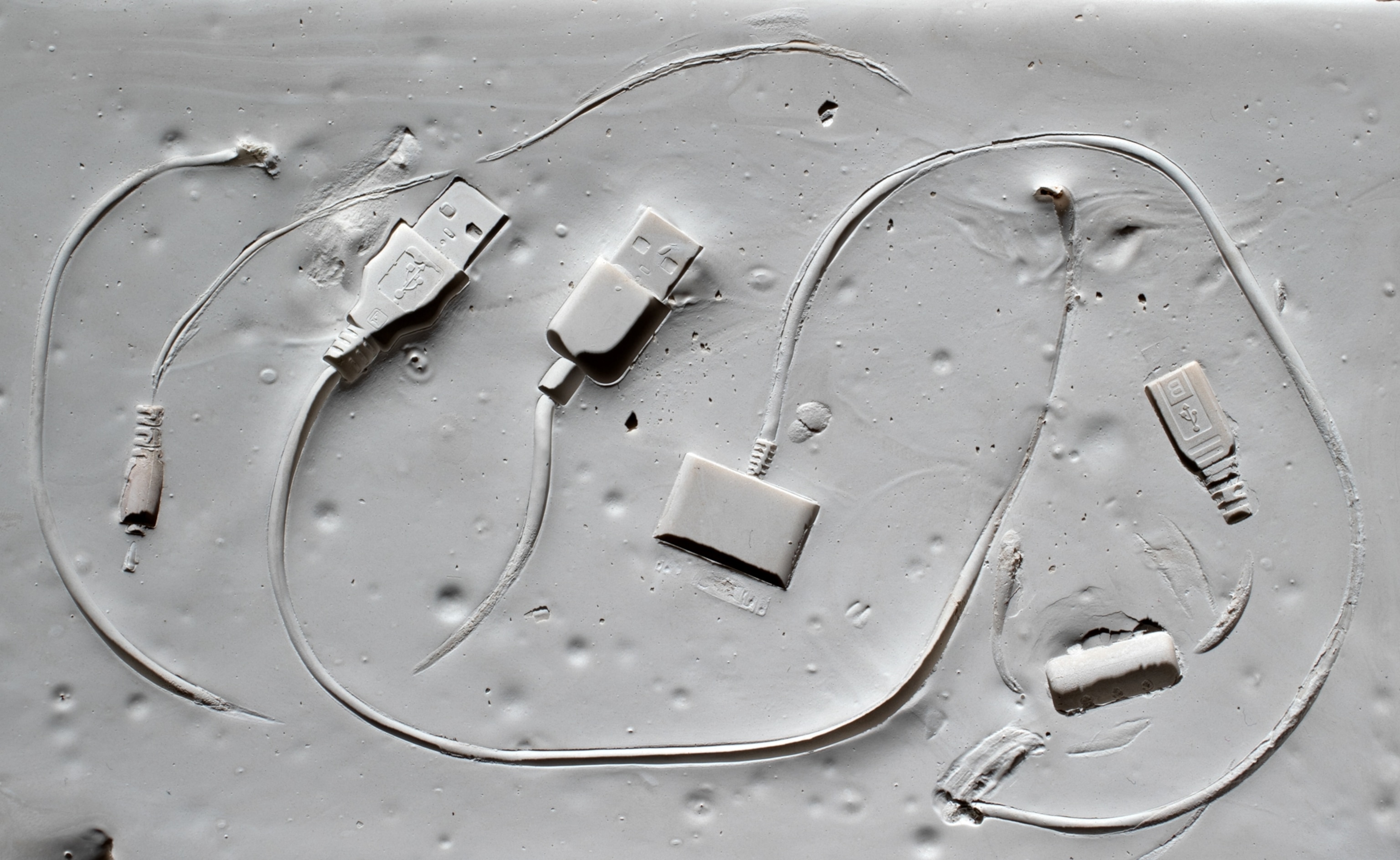

Even without their silicon hearts, computing devices will be recognizable as unique objects by the paleontologists of the future. They will be part of our legacy of e-waste, a rapidly growing category of trash. In 2022, humanity produced more than 62 million tons of e-waste, objects laden with materials both precious and poisonous, from lead to cobalt to gold. Although some e-waste is recyclable, around 80 percent of it ends up in landfills, where it will likely remain for thousands of years.

In thinking about how our e-waste could be interpreted thousands of years in the future, Gabbott and Zalasiewicz landed on one device that will appear repeatedly in the fossil record: the keyboard. They imagined our distant successors unearthing hundreds of similarly shaped, regularly textured objects, etched or printed with symbols. If these paleontologists operate as we do, they’ll begin by looking for patterns in their fossils and attempting to trace where one subspecies of object branched off from its predecessor.

“If you found a bunch of smartphones in isolation, it would be virtually impossible to tell what they were,” Gabbott says. “But if you find a typewriter first, you’ll see the keys and the patterns on it. A laptop will be similar but with a big screen taking up half the device.” From there, it wouldn’t be impossible to deduce that a smartphone was a further evolution of technology, a refinement of the idea.

“Of course, interpreting all of it would depend on whether [our descendants] developed their own technology or not,” Zalasiewicz adds.

(Human-made materials now equal weight of all life on Earth.)

The forever of forever chemicals

Not all our technofossils will be so legible. Some of our most dangerous innovations are undetectable by the naked eye. There are over 350,000 chemicals registered for industrial use, many of which are currently settling into the soil or sloshing around in the groundwater. Some are highly toxic. Pesticides easily bind with tiny particles of sediment, which then make their way into the atmosphere. Rainfall brings these chemicals down to Earth, polluting seemingly pristine bodies of water. Around the world, lake beds are now marred with layers of these technofossils. If the soil layers are disturbed, they can be released again into the water, where they can make their way back into the food chain. A million years from now, these forever chemicals could reemerge to poison whatever creatures come next.

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are both a here-and-now problem and a future issue, since these human-made chemicals are highly stable, breaking down only under conditions of extreme heat. Teflon, a substance commonly used to coat nonstick pans, is perhaps the most famous type of PFAS. This material is so chemically resilient that it’s likely to outlast its metal undergirding, existing indefinitely as a thin, flexible, round layer of film. It will not rot or degrade, though it can shed pieces of itself into the surrounding environment almost without limits.

“I used to have this idea that these persistent organic pollutants would go into the ground for a few hundred or a few thousand years, and they would decay,” says Zalasiewicz. “That clearly doesn’t happen.” Instead, they’re building up in soils, waters, and in our fat layers.

“That’s very sobering, you know,” he says. “It’s worrying.”

The persistence of things is undeniable. It was by design—originally, we created objects to be long-lasting so we wouldn’t have to replace them. We made our possessions strong so that we could hold on to them. This is, perhaps, the central argument of Discarded: Disposability is a myth. Each item that leaves our lives goes on a journey. These things do not simply disappear. They have already left an indelible mark on the planet, but what happens next isn’t set in stone.

“I think back to the milk bottles of my childhood,” says Zalasiewicz. He remembers how, each week, the empty bottles were collected from his doorstep and reused. They weren’t thrown out; for as long as they were intact, they had use. “We’ve lost that world,” he says. Our patterns of consumption aren’t ancient or immutable. What changed once could change again.