This U.S. governor was impeached—for cracking down on the KKK

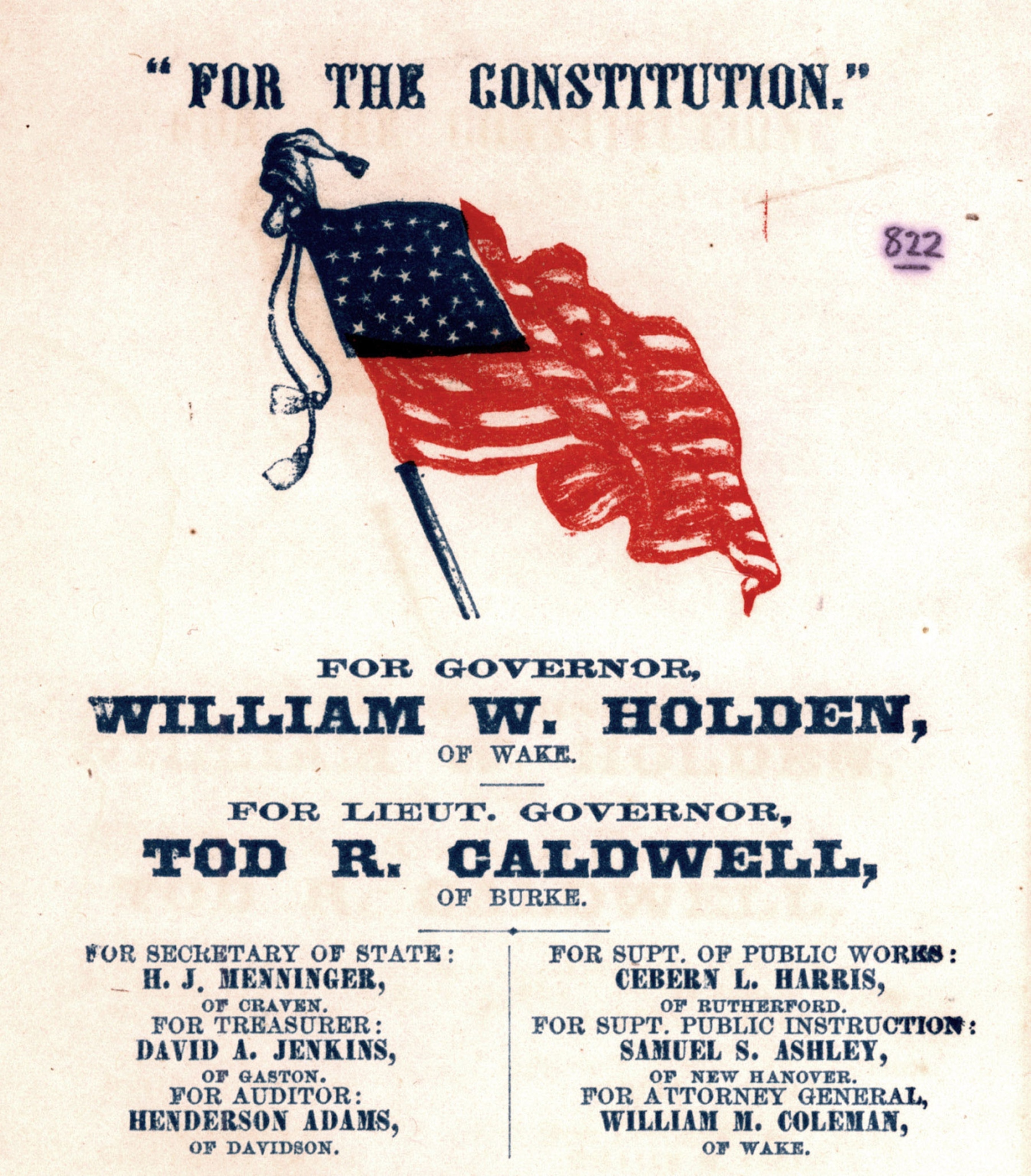

150 years ago, North Carolina Governor William Woods Holden suppressed a white supremacist insurrection—and lost his job as a result.

A century and a half ago, North Carolina’s Ku Klux Klan was ascendant. Fueled by backlash to Reconstruction, groups of masked men roamed the state, terrorizing and murdering Black citizens and government officials opposed to the Klan violence. Governor William W. Holden, a Republican who supported Black suffrage (despite opposing it prior to the Civil War), attempted to stop the lawlessness by appealing to local officials and members of the rival Conservative-Democratic Party, a coalition of opponents to Reconstruction. But the outrages mounted, culminating in a string of high-profile assassinations.

In May 1869, a group of men shot and killed “carpetbagger” Sheriff O.R. Colgrove of Jones County. Soon after, M.L. Shepard, the county’s Justice of the Peace, was gunned down, and several of his men wounded. In February 1870, town councilman Wyatt Outlaw, the leading Black leader in Alamance County, was lynched by about 60 members of the White Brotherhood, outside the courthouse in the town of Graham. The assassins left a note on the Republican mayor’s door that he’d be next.

Conservative newspapers downplayed the violence or claimed it was the work of Union League members in disguise. If charges were brought, the suspects walked free thanks to fake alibis, witness intimidation, or rigged juries.

The final straw was the shocking murder of Republican State Senator John W. “Chicken” Stephens. The senator was ambushed at the Caswell County courthouse, where he was attacked and murdered by a group of Klansmen. When the body was discovered, the authorities took little action to uncover the culprits (it was later revealed the man who lured Stephens to his death was the county’s former sheriff).

“In Caswell and Alamance, the Klan pretty much overthrew the government,” says William C. Harris, a historian based in North Carolina and the author of a biography of Holden. “Stephens’ killing was the thing that got Republicans to move.”

Holden and the state’s Republicans determined that military intervention was the only solution. The governor proclaimed Alamance and Caswell to be in a state of insurrection and declared martial law. Holden then asked President Ulysses Grant to intervene, but the sluggish federal response led the governor to instead muster a state militia. (Reconstruction offered a glimpse of equality for Black Americans. Why did it fail?)

The Kirk-Holden War

Holden enlisted the help of George Washington Kirk, a colonel who’d commanded a group of Union troops in the region during the Civil War. Kirk was notorious among the state’s Conservatives as “a guerilla bandit from East Tennessee” as one paper called him, who seized the property of Confederate supporters in the Western North Carolina mountains.

“Kirk was not the best choice as far as settling things down,” says Harris.

Kirk assembled more than 600 soldiers, and over a few weeks in July 1870, the army rounded up more than 100 Klan members suspected of violence—including many respected figures—and Holden attempted to try them in military courts. Despite public concerns that the operation could turn violent, little blood was shed during the Kirk-Holden War, as it became known. But the backlash to the operation was fierce.

Holden’s critics saw the campaign as an outrageous act of tyranny or, at best, a voter intimidation tactic ahead of the August state congressional election. Even the New York Times, largely supportive of a Klan crackdown, criticized how “the Executive of a reconstructed State may usurp functions not contemplated by the Constitution under which he was elected, and may become the despotic master of a people whom he is supposed to serve.”

Holden lifted martial law shortly after the election and revoked the insurrection proclamations on November 10, but his rivals were not interested in reconciliation.

When the new legislature met, the lawmakers voted 60 to 46 to impeach Holden. Eight articles of impeachment were brought against the governor, including the unlawful declaration of insurrection and the denial of procedural rights of those arrested. (Here's the history of presidential impeachment.)

Governor Holden on trial

The state Senate began Holden’s trial in January 1871. The prosecutors, a prestigious team that included two former North Carolina governors, brought 61 witnesses and portrayed Caswell and Alamance as places of peace, making actions taken by Holden unconstitutional.

The defense presented the reverse, bringing 113 witnesses, including former Klansmen, who testified to numerous atrocities and the failure of local authorities to take action. The gruesome descriptions of the terrorizing and murder of Black citizens and their white supporters made it clear these efforts were an attempt to overthrow the law itself.

As for the constitutionality of Holden’s actions, his defense team argued that the Shoffner Act, passed the year before, permitted the governor’s use of the state militia (although it didn’t permit the use of military tribunals).

In the closing days of his trial, the governor rushed to Washington to plead his case.

“Holden met with Republicans in Congress,” says Harris. “He met with President Grant, who was beginning to change his mind that there was a problem, that there was a wide-scale insurrection, as all this evidence was coming out about the Klan violence in North Carolina and other Southern states.”

But the support came too late. On March 22, 1871, 44 days after the trial began, the Senate rendered its verdict. On the six articles charging him with raising an illegal military force and violating the rights of those arrested, he was found guilty, with several Republicans joining with the Conservatives on the charges. He was found not guilty on the two charges that he’d unlawfully proclaimed Alamance and Caswell counties in a state of insurrection, with six Conservatives joining the Republican minority. But with 36 Conservatives and 14 Republicans in the Senate, voting broke largely along party lines.

With that verdict, Holden became the first U.S. governor in history to be convicted and removed from office. He was immediately removed from the governorship and prohibited from ever again holding statewide office.

The legacy of Holden’s impeachment

Holden’s impeachment had a lasting impact. Just six days after the governor’s conviction, Congress introduced the Third Force Act, giving the president permission to intervene when states tried to deny “any person or any class of persons of the equal protection of the laws, or of equal privileges or immunities under the laws.”

Key to passing the Third Force Act were the details from Holden’s trial.

“The testimony from North Carolina was central to demonstrating that there was a widespread effort or conspiracy of violence that the local authorities could not or would not put down,” says Harris. “That affected all of the South, and it did for a time suppress that kind of violence.”

Though the “scalawag governor” served as a favorite villain of North Carolina Conservatives for decades after his impeachment, Holden’s reputation began to be reevaluated following the Civil Rights Movement.

In 2011, the North Carolina State Senate retroactively pardoned the governor for his crackdown on the Klan. The effort aimed to formally repudiate the 140-year-old decision and restore Holden’s reputation.

“He was someone who was really trying to bring the South together during that period of Reconstruction,” says Floyd McKissick, Jr., a former North Carolina State Senator who helped pass the pardon. “It required a certain amount of political courage to stand up to that, and he paid the price for being on the right side of history.”