Here's why Veterans Day was originally called Armistice Day

The U.S. holiday began as a celebration of the end of WWI. But in the wake of even deadlier conflicts, November 11 became a day to honor all military veterans.

Parades, ceremonies, and a much-needed day off—Veterans Day, observed on November 11 each year, is one of the nation’s 12 Congressionally designated federal holidays. The holiday is distinct from Memorial Day, which grew out of the Civil War-era tradition of decorating the graves of deceased soldiers. While Memorial Day honors those who died in military service, Veterans Day celebrates the living and the dead.

But Veterans Day didn’t always celebrate all military veterans. Once known as Armistice Day, it has roots in one of the most destructive conflicts in history. Here’s how the holiday evolved from a day of postwar mourning to a celebration of all those who have served in the U.S. Armed Forces.

The first Armistice Day

The holiday’s beginnings can be traced to the late days of 1918, when a weary world began to look toward the end of what was commonly called the “Great War.” Over four long years, World War I had obliterated European landscapes, ushered in the use of deadly new technologies such as poison gas, and entangled more than 30 nations. Revolutions had upended the governments of many of the combatant countries, and an influenza pandemic was sweeping the world.

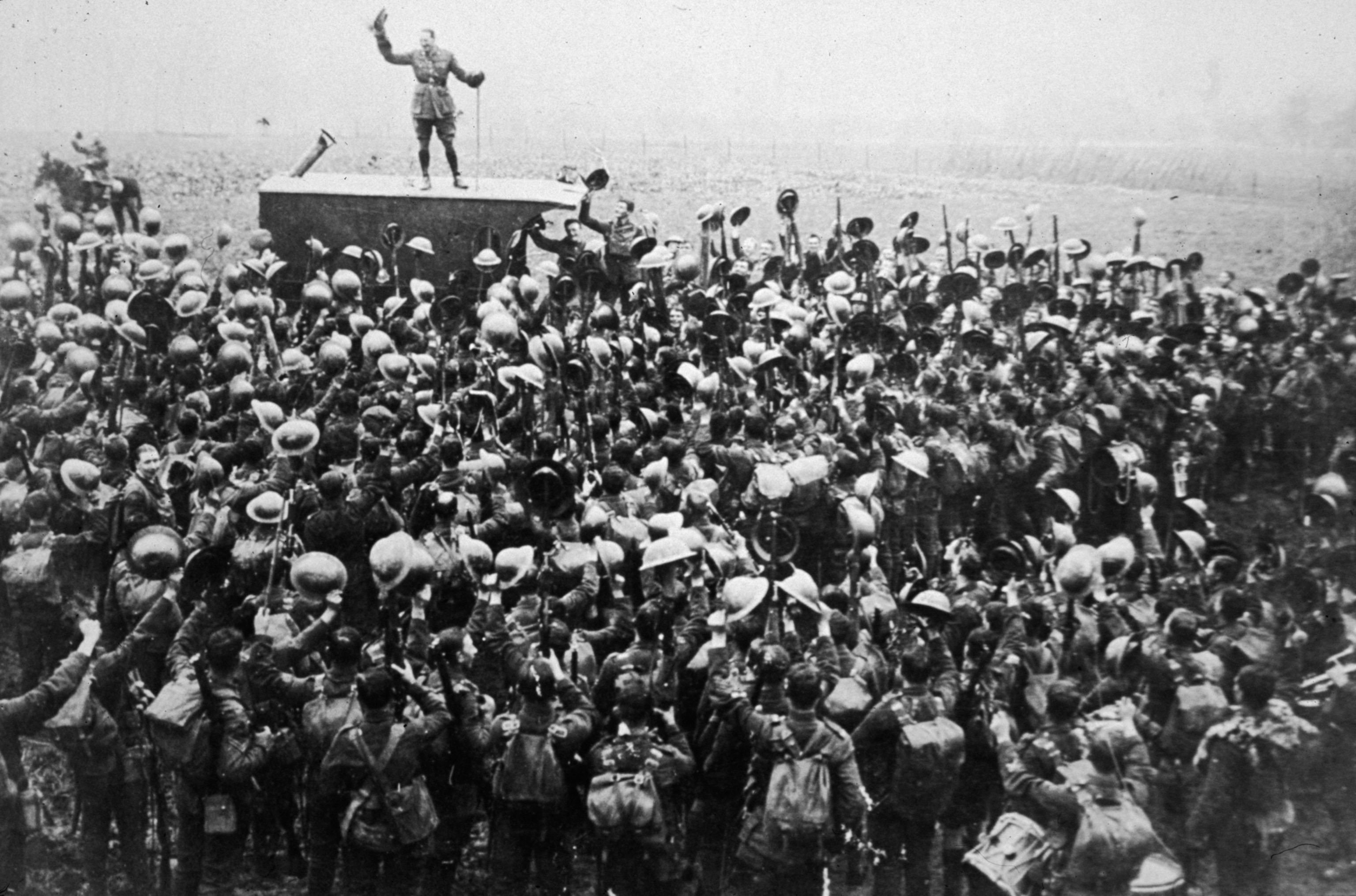

After a long stalemate, the United States entered the war, and the Allied forces launched an offensive that would prove decisive. The Allies’ terms were tough, but Germany was in no position to argue. Finally, on November 11 at 11:00 a.m. Paris time, an armistice came into effect.

World War I was over, but the world reeled from its losses. A total of about 10 million men were killed in action, and another 20 million were wounded worldwide. The U.S. had only joined the conflict in 1917, but it alone had lost over 116,000 lives and seen about 320,000 other casualties. Those losses were bitterly felt, especially among those whose loved ones had been buried in over 2,300 temporary cemeteries on European soil.

A year after the armistice, Americans made plans to observe the anniversary nationwide. Multiple governors declared legal holidays. Veterans’ associations and groups around the country made plans to commemorate the occasion with ceremonies, religious ceremonies, and fundraising for the American Red Cross. On November 11, 1919, the New York Times noted that people around the world would hold moments of silence at 11:00 a.m.

President Woodrow Wilson issued a message in commemoration of the anniversary. “To us in America,” he wrote, “the reflections of Armistice Day will be filled with solemn pride in the heroism of those who died in the country’s service, and with gratitude for the victory.”

The evolution of Armistice Day

The ceremonies became an annual observance among many who wanted to keep the memory of the war alive, and by 1926 the U.S. Congress had adopted a resolution urging President Calvin Coolidge to issue annual Armistice Day proclamations. In 1938, November 11 was designated Armistice Day nationwide by act of Congress, which said that the day should be “dedicated to the cause of world peace.”

But world peace proved elusive. Though World War I had been dubbed “the war to end all wars,” the world plunged back into conflict. In 1941, the U.S. entered World War II—which would become what is still known as the world’s deadliest conflict. Over 291,000 American soldiers died in battle, and another 670,000 were wounded. The Korean War followed in 1950, leading to the deaths of nearly 34,000 American soldiers and another 103,000 wounded.

(75 years after the Nazis surrendered, all sides agree: War is hell.)

By that time, Armistice Day had begun to seem outdated, as most veterans had been born after World War I ended. In 1953, Alvin J. King, an Emporia, Kansas, cobbler who had lost a nephew during World War II, petitioned the city to rename the holiday to honor all who had served. That year, the city celebrated Veterans Day on November 11 instead.

Emporia’s U.S. congressman, Edward H. Rees, took up the cause and proposed a federal name change. “Armistice Day unfortunately is not being observed the way it ought to be observed,” Rees said during a Congressional hearing on the matter. The holiday would “give recognition to the fact that before and since World War I, millions of United States men have fought and died under the flag of the United States in the furtherance of world peace.”

Congress agreed, and the name change became official in 1954.

The Uniform Monday Holiday Act

In 1968, Congress passed a law that moved four federal holidays, including Veterans Day, to Monday, bowing to pressure from a coalition of travel and tourism groups that argued more three-day weekends would stimulate the economy. In a statement upon signing the bill, President Lyndon B. Johnson said the law would “help Americans enjoy more fully the country that is their magnificent heritage,” visit their families, and travel farther.

The move enraged veterans’ groups. “We look at this as a legislative distortion of history,” American Legion commander William C. Doyle told the Associated Press, “an…accommodation to our economic system—the almighty dollar, if you will—at the expense of historical fact.”

When the change went into effect in 1971, pressure mounted and most states changed their observances of the holiday back to November 11. In the face of growing confusion, in 1975 Congress held hearings on whether it should change the federal holiday back.

Legislators weighed everything from weather to the number of times November 11 would fall on a Monday, and heard testimony on both sides of the issue. “The emotion and feeling in the hearts of our World War I veterans and citizens of that era who recall the impact of the ceasefire on the 11th month, the 11th day, and the 11th hour in 1918 should serve as the cornerstone as this generation attempts to build a permanent framework for peace throughout the world,” said Kansas Representative Keith G. Sebelius.

Ultimately, the veterans won the day and Congress moved Veterans Day back to November 11. The change went into effect in 1978, and the federal holiday has been celebrated on the 11th ever since.