Why 'close-call' presidential elections are happening more often

Although the country has historically seen some incredibly tight elections—including a literal tie in 1800—polarization is making such victories increasingly likely.

In U.S. presidential elections, it’s rare that the race is so close that the nation goes to bed on election night not knowing who won. Yet that’s what America woke up to on the day after—a contest between Democrat Joe Biden and incumbent Republican President Donald Trump that remains too close to call, even with a record-shattering voter turnout.

Votes are still being counted, but in an unprecedented election night declaration, Trump claimed victory in the wee hours and called for vote-counting to halt as he made allegations of fraud despite lack of evidence. The vote-counting continues, as it does in every election, as absentee and mail-in ballots are tallied. Amid the pandemic, a record-breaking number of these ballots were used to vote this year.

“No president in history has ever stood up on election night and declared himself the winner and attempted to call off the vote count,” says Eric Alterman, a historian and writer who teaches at Brooklyn College in New York.

Modern polarization

The 2020 race is the third presidential election of the last six that’s gone down to the wire. In the end, the winning margin in the Electoral College may not be close. Or, the 2020 election could displace the 2000 election between Republican George W. Bush and Democrat Al Gore as the most contentious election of the group.

“Given the polarization of our electorate today, we’re never going to see a 60 percent landslide or a 20 percent margin in the popular vote,” says Bruce Schulman, an American history professor at Boston University. Americans are just so closely divided along party lines that wide margins of victory are becoming rarer.

The outcome of the Bush-Gore race remained unresolved for more than a month after Election Day. Ballot irregularities—including the famed “hanging chads”—prompted a recount in several Florida counties and set in motion a series of lawsuits, with appeals up to the U.S. Supreme Court. On December 12, the high court ordered the recount to end. Bush led Gore in the Florida count by 537 votes and thus won the state’s 25 electoral votes. It was enough to give him a narrow victory in the Electoral College—271 votes to Gore’s 266—even though Gore had won the popular vote nationwide by more than 500,000 ballots.

In 2016, Trump lost the popular vote to Democrat Hillary Clinton by 2.9 million votes, but carried the Electoral College with 304 votes to Clinton’s 227. Trump eked out a victory by narrowly winning three Rust Belt states—Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—by less than one percent of the vote in each. Combining vote totals in all three states, he bested Clinton by fewer than 80,000 votes. Clinton lost Michigan by a mere 10,704 votes. In all, nearly 139 million votes were cast nationally.

In 2020, the race will be decided once again in those Rust Belt states. But the 2020 election stands out because pundits had predicted two opposing scenarios right up to Election Day—it could be either a landslide or very close. In the case of a close election, the pundits also foresaw legal combat that could arise out of Trump’s repeated claims of fraud that date to his first campaign in 2016.

During that campaign, then-candidate Trump regularly raised questions about potential election rigging. And during his first week in office in 2017, Alterman notes the president asserted, without evidence, that three million non-citizen immigrants had voted illegally, and set up a commission to search for voter fraud. No fraud was found and the commission was disbanded. Voter fraud in the United States has occurred in isolated and infrequent instances; multiple investigations have never substantiated claims of widespread cheating.

Voter fraud “is vanishingly rare, and does not happen on a scale even close to that necessary to ‘rig’ an election," writes Justin Levitt, counsel for the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law. In a 2007 analysis, the center found incident rates of between .0003 and .0025 percent, meaning a voter had a higher likelihood of being struck by lightning, or by a car on the way to the polling place.

Still, as this election approached, Trump suggested at rallies that some version of fraud could exist in mail-in and absentee ballots. He also declared that voting should stop on election day, and Republican lawyers went into court in several states, including Pennsylvania, where they unsuccessfully argued that ballots arriving after election day not be counted. The Supreme Court allowed state officials to count mail-in ballots received up to three days after the election.

That runup set the stage for post-election chaos in swing states with large numbers of mail-in and absentee ballots that could stretch on for weeks.

Historical nail-biters

In modern presidential elections, the closest popular vote tally remains the 1960 race between Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy, a Democrat, and Richard Nixon, who was then serving as vice president to Republican President Dwight Eisenhower. Neither man claimed a majority of the vote; Kennedy won 49.7 percent, and Nixon won 49.5 percent, separated by fewer than 113,000 votes. (Kennedy carried the race with 303 electoral votes, far outstripping Nixon’s 219; the remaining electors supported Harry Byrd, a segregationist Democrat senator from Virginia who was also on the ballot.)

The race was won in Texas and Illinois—for different reasons. Kennedy’s running mate Lyndon B. Johnson helped secure his home state of Texas, while Chicago Mayor Richard Daley turned out enough Democratic voters in Cook County to offset southern Illinois where Nixon ran ahead. Republicans later claimed that Daley stole Cook County, in what has since become one of the most enduring, if unproven, allegations of widespread election shenanigans. The myth goes, Schulman says, that “all Cook County residents, living and dead, voted early and often.”

In fact, the demographics of Cook County were favorable to the Democrat. “You don’t need fraud to explain how Kennedy got the numbers that he did,” writes Paul von Hippel, a public policy and data science professor at the University of Texas, in The Washington Post.

Yet the fact is, Schulman says, that a shift in votes by less than one percent in Texas or Illinois “could have made a difference.”

One of the closest elections that rarely gets mentioned is the cliff-hanger in 1880 between Republican James Garfield and Democrat Winfield Hancock. Although Garfield won 214 electoral votes to Hancock’s 155, Garfield only defeated Hancock in the popular vote by 7,368 votes—one of the smallest margins ever recorded.

“If you look at the Electoral College, it seems like a pretty decisive victory,” Schulman says. “But he won less than one-tenth of one percent of the popular vote.”

Close elections don’t get much stranger than the election of 1800, when Thomas Jefferson defeated incumbent President John Adams, but tied with his own running mate, Aaron Burr, since presidents and vice presidents were not listed separately on the ballot at the time. The tie forced the election into the House of Representatives, where neither man won on the first 35 ballots. After negotiations convinced several Federalist congressmen to switch their allegiances from Burr, Jefferson won on the 36th ballot.

The election of 1876 also was decided by the House of Representatives when Republican Rutherford B. Hayes ran against Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, governor of New York. The campaign was deeply divisive in ways not seen in national elections of that era. Tilden won the popular vote, but 19 Electoral College votes were in dispute, leading to allegations of fraud. Congress set up a commission to determine the winner. Just two days before the inauguration was to be held, Hayes was declared the winner by a single vote on the 36th ballot.

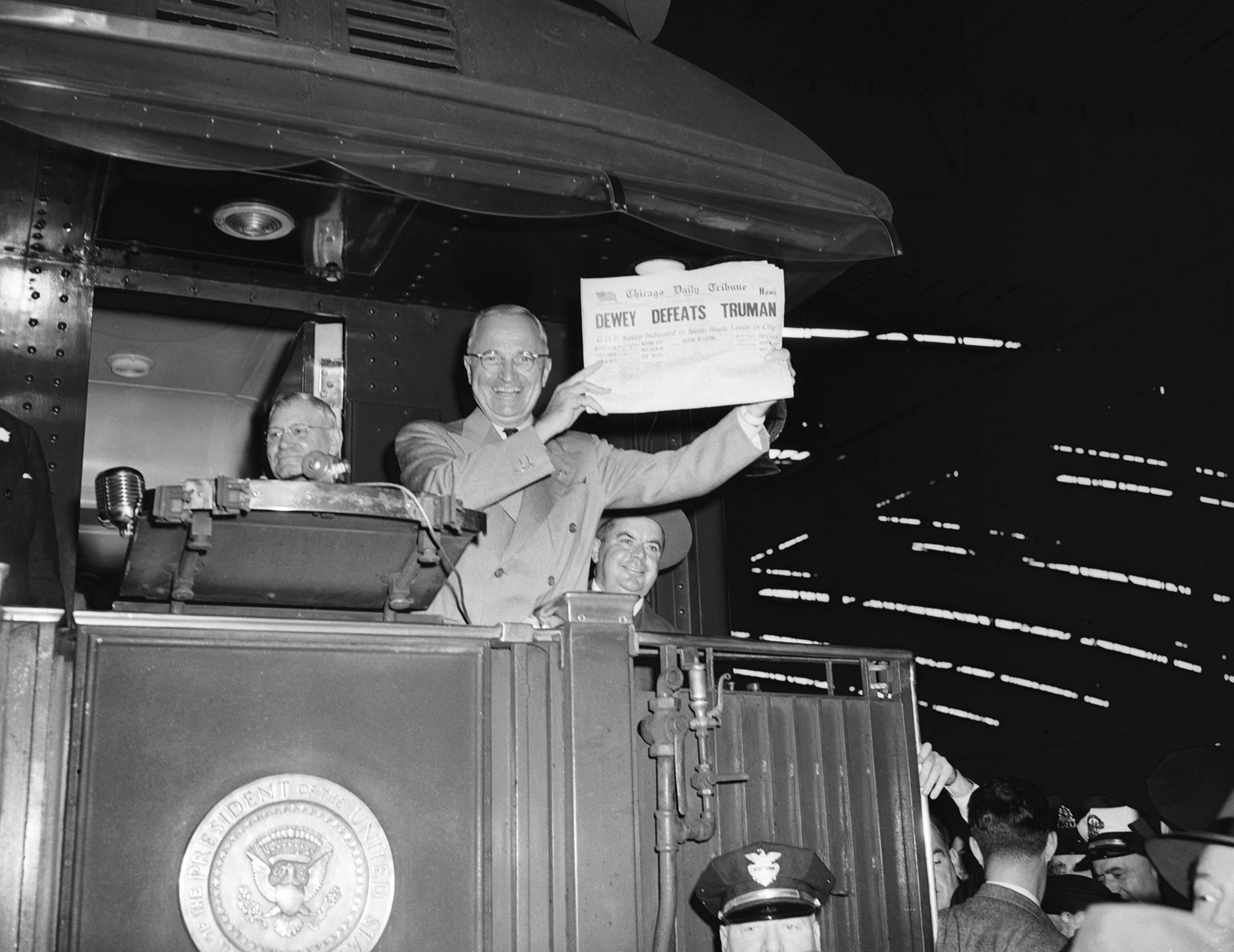

A big reminder of the perils of announcing close elections came in 1948, when President Harry Truman was predicted to lose. Truman, who had succeeded President Franklin D. Roosevelt after he died in office, faced a strong challenge from Thomas Dewey, a Republican governor from New York. On election night, the Chicago Daily Tribune declared Dewey the winner in what the Tribune still refers to as the most famous wrong call in electoral history: A massive headline that declared, “Dewey Defeats Truman.”

It was yet another election in which neither candidate won 50 percent of the vote. Truman tallied 49.6 percent to Dewey’s 45.1 percent, with the remaining 2.4 percent going to a spoiler candidate, Strom Thurmond, then governor of South Carolina who ran as a “Dixiecrat.” Truman carried the Electoral College by a wide margin—303 to Dewey’s 189 and Thurmond’s 39. But it is that black-and-white photograph of him, wearing a broad grin and holding up the Tribune’s front page, that lives on in infamy. To this day, it serves as the best caution to modern prognosticators: Don’t get ahead of the final count.