How Europe went cuckoo for cocoa

Sacred to the Maya in the New World, cocoa took on a new life when it hit the shores of the Old World. Lauded by royalty, denounced by the church, and embraced in the kitchen, chocolate became the most fashionable drink in all of Europe.

In May 1502, Christopher Columbus set out on his fourth voyage to the New World. From this trip, he brought back many things to Europe: gold, silver, and a plain-looking cargo of beans. The Spaniards weren’t impressed and largely overlooked them. At that time no one could have predicted just how much these unassuming beans would end up transforming Spanish and European cuisine.

Two short centuries later, the capital of the Spanish Empire was overrun by chocolate and consuming more than five tons every year. According to contemporary records, there was not a street in Madrid where chocolate could not be bought and drunk. How did the humble cacao seed of a South American tree become the latest craze in Europe?

Chocolate and Chili

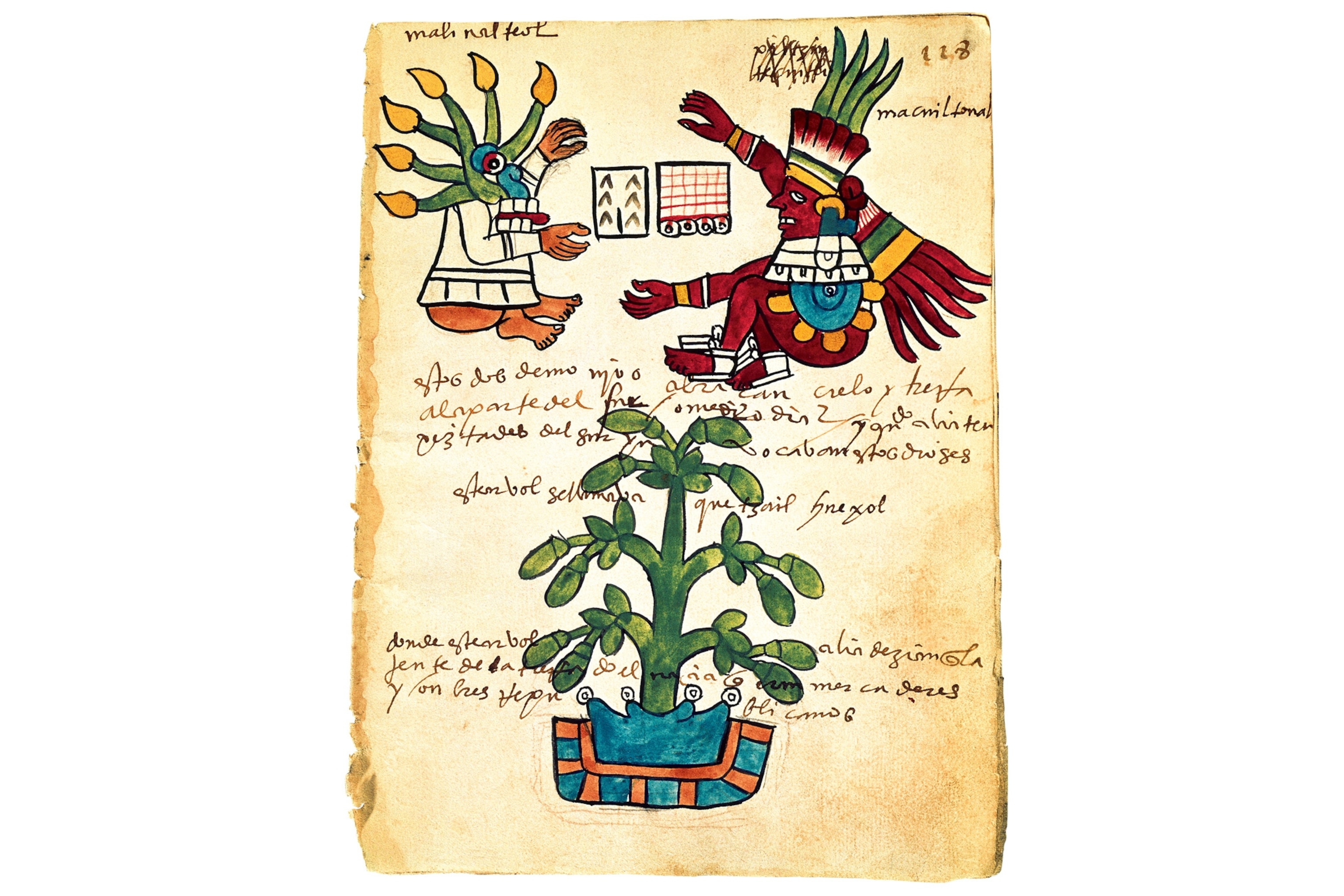

The Maya were among the first to fall under chocolate’s spell. The Madrid Codex, preserved in the Museum of the Americas in Madrid, Spain, contains the first written records of its consumption. The codex confirms that the Aztec believed that cacao beans were divine and seen as no less than a physical manifestation of Quetzalcoatl, god of wisdom. (See also: Chocolate gets its sweet history rewritten.)

As Spanish rule extended through the New World, the importance of cacao to the peoples they colonized became impossible to ignore. Cacao was valued so highly by the Aztec that it formed part of their monetary system. In order to understand the commercial transactions of the Aztec world, the Spaniards even created tables to show the trading value of specific amounts of cacao beans. (See also: Rare Aztec Map Reveals a Glimpse of 1500s Mexico.)

Health Food? Chocolate and Cake

In the first half of the 18th century, the French traveler and clergyman Jean-Baptiste Labat journeyed extensively through the New World. In his reports, he wrote of the importance of chocolate to colonizers and colonized alike: “The Spaniards and other nations that imitate them, make slices of sponge cake or bread which they dip into the chocolate and eat before drinking the rest. This seems a sensible approach: the impurities found in the stomach stick to this bread and chocolate and so pass through the body more quickly.” Labat also described how in the parts of the New World through which he had traveled, chocolate “was used to make small tablets as well as a type of jam or spread. It would be most desirable for the use of this excellent foodstuff to be established here in France, as it is in Spain and throughout America.”

At first, the conquistadores kept their distance from chocolate. As the chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo complained, the lips appear stained with blood after drinking it. The Aztec often mixed it with chili, a flavor alien to the Spanish palate. “Chocolate seemed more like a drink for pigs than something for human consumption,” wrote Girolamo Benzoni in his history of the New World. (See also: Prehistoric Americans Traded Chocolate for Turquoise?)

But attitudes changed rapidly when Hernán Cortés returned to Spain from his bloody conquest of Mexico in 1521. He presented the Aztec drink made from cacao beans to King Charles V. Adjustments to the recipe were made, sugar was added, and chocolate soon became popular among the higher echelons of Spanish society. A new fad had been born.

Chocolate and Theology

In Spain, the laborious task of grinding cacao beans fell to the molendero. This itinerant figure would crisscross the country with a curved grindstone strapped to his back. Kneeling in front of his grindstone, he used a mortar to crush the tough coating of the beans. Little by little, and through enormous physical effort, the crushed beans would cohere into a smooth wet substance known as cocoa paste. In one of his poems, the late 18th-century Valencian writer Marcos Antonio Orellana invokes a sense of reverence toward the production of chocolate that the Maya might identify with: “Oh, divine chocolate / kneeling they grind thee / with hands praying they stir thee / and with eyes raised to heaven they drink thee!"

Cups, Saucers, and Pastries

During a tour of Spain at the end of the 17th century, Madame d’Aulnoy attended a tea party held by the Duchess of Terranova in her palace. Chocolate was served in porcelain cups. The saucers were made of agate decorated with gold, and there was a sugar bowl to match. The chocolate was drunk either cold, hot, with milk or with eggs, and accompanied with specially made little pieces of toast or sponge cake. Some people drank as many as six cups of chocolate, one after the other, two or three times in the course of a day.

Monasteries were amongthe major consumers of chocolate, buying the drink in large quantities. The Cistercian monastery of Piedra, in Aragon, is said to be the first place in Spain where chocolate was prepared, and became a firm favorite among the monks there—but not all religious orders approved. The Jesuits believed that it went against the precepts of mortification of the flesh and poverty.

The question as to whether such a rich beverage should be drunk during periods of fasting sparked a theological debate between defenders and detractors of the chocolate habit. The 17th-century theologian Cardinal Francesco Maria Brancaccio gave a definitive answer to the vexed question in his now famous decree: “Liquidum non frangit jejunum—Liquid does not break the fast.”

Chocolate Etiquette

Publicized as an exotic drink from the Indies, the consumption of chocolate spread across Spain throughout the 17th century. The habit became so widespread that aristocratic women took to drinking it to keep themselves awake through long church sermons—a practice that ended with it being banned from churches by the bishops.

Among the nobility of that period, no afternoon reception would have been complete without the ritual of serving a cup of hot chocolate, accompanied by fingers of sponge cake or cookies for dunking. In winter, the beverage was enjoyed at firesides among soft cushions and colorful tapestries. Chocolate drunk at a summer reception was often served with ice.

The 17th-century version of the drink was much thicker than the kind of hot chocolate mostly drunk now. Spillages could often stain clothes and upholstery. Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, viceroy of Peru and first Marquis of Mancera, came up with a solution to that problem in 1640. He suggested making a small tray with a central clamp to which the chocolate pot—the jícara—would be fixed, so as to prevent its being knocked over or leaving messy drips. In honor of its inventor, the tray was called a mancerina. Depending on the social standing of the host, mancerinas could be made of silver, porcelain, or pottery.

Fading Fad

The rest of Europe, and especially France, soon fell under the spell of the cacao bean, thanks in great part to Anne of Austria, the daughter of Philip III of Spain. When she married Louis XIII of France, she brought with her the royal Spanish custom of drinking chocolate at breakfast time. Later, the wife of Louis XIV, Marie-Thérèse—another chocolate-loving Spanish princess—consolidated the supremacy of chocolate in the French court.

When the Bourbon dynasty was installed in Spain, its members became chocolate connoisseurs too, especially Philip V and his son Charles III. In his zeal to develop Spain through trade and industry, Charles III saw the potential economic value of cacao beans and allowed a monopoly on their trade between Madrid and Venezuela.

As a result, chocolate soon began reaching the tables of Spain’s wider social classes. Grocery shops specializing in products from the Spanish colonies catered to newly acquired exotic tastes. The habit of drinking chocolate became attainable for many people.

From the beginning of the 19th century, however, new industrial methods allowed even higher consumption at a much lower cost. Soon chocolate was replacing tea and coffee as the drink of choice. In Europe, at least, cocoa had become an everyday commodity, a world away from the holiness and mystery of its South American origins.

Oddly enough, culinary uses for chocolate were slower to take hold. It was only in the 18th century that it began being used in desserts and cakes. In his 1747 book, The Art of Confectionary, Juan de la Mata included recipes for sweets made with chocolate, among which was a novelty. De la Mata called it “foam”—the prototype to chocolate mousse. Chocolate candy bars first began to appear in the 19th century, creating a solid way for the world to go crazy for chocolate.

The Proper Steps

1. Building Blocks

After roasting, the cacao bean is ground and blended with vanilla, cinnamon, and sugar to make a fine paste. This is then formed into blocks.

2. Melting Down

The blocks are heated in a copper urn. A long stirring implement is passed through a hole in the lid to mix the melting chocolate.

3. Pouring Out

The chocolate drink is then poured into a serving pot made of porcelain or silver with a hinged lid and handle.

4. Drinking Up

The chocolate is drunk hot from little cups called jícaras or pocillos, which are served on the specially designed trays known as mancerinas.