Coca: A Blessing and a Curse

South Americans have cultivated coca plants for about 8,000 years. Valuing the leaves as highly as gold, the Inca treasured coca not only for its myriad medicinal properties, but also for the integral part it played in their sacred rites and rituals.

A legend from the Andes tells the tale of Kuka, a woman of such extraor dinary beauty that none in the entire empire could resist her. Aware of her power, Kuka used her charms to take advantage of men until word of her misdeeds reached the Great Inca’s ears. He ordered that she be sacrificed, cut in half, and buried. From her grave a miraculous plant sprouted. It gave strength and vigor and alleviated pain and suffering. The people called it coca, in honor of that beautiful and irresistible woman.

This myth acknowledges the great importance that coca leaves had, and continue to have, in the culture and history of the people of the Andes. Despite gaining notoriety in modern times for being the source material for the highly addictive drug cocaine, coca continues to be a large part of Andean culture today. Unprocessed leaves from the plant can be enjoyed by chewing them or by brewing them into a tea. Locals still use coca today to combat altitude sickness, and to relieve pain and hunger. Some still believe that its leaves can be read to tell the future.

Scientific studies of coca’s medicinal properties have found that its leaves contain a powerful alkaloid that acts as a stimulant. Its effects include raised heart rate, increased energy, and even suppression of hunger and thirst.

Other benefits include muscle relaxation, which can help with menstrual cramps. This effect also helps to treat altitude sickness by opening up the respiratory tract and relieving the feeling of shortness of breath and tightness in the chest. Coca is highly useful for its antibacterial and analgesic properties, in addition to aiding in digestion and in preventing constipation. Coca itself is rich in iron, and vitamins B and C.

Consumption of coca dates back to the very earliest of ancient South American societies. There is evidence it was consumed in cultures located in modern-day Ecuador from as early as the ninth millennium B.C. It was during the Inca Empire, however, a little before the arrival of the Spanish, that coca attained particular religious and socio-economic significance.

Coca Culture

The first Incas date to A.D. 1200. The civilization rose to prominence in 1438 when the emperor Pachacutec, whose name means “he who remakes the earth,” began conquering lands surrounding Cusco, the imperial capital, located in modern-day Peru. The Inca language, religion, and trade network dominated the Andes.

Vast amounts of coca, regarded as sacred by the Inca, were used in religious ceremonies. Cristóbal de Molina, a Spanish priest who lived in Cusco around 1565 and observed Inca traditions, described how the Inca burned leaves and blew coca fumes toward the sun—their main deity—and other gods, as part of a ritual to heal the sick. The plant was also revered for its divinatory powers, and some priests were specialists at reading its leaves. Coca was also buried with the dead, included among their grave goods to accompany them into the afterlife.

Some religious rituals involved human sacrifice, and coca played a role as well. Three mummies of sacrificial victims discovered in 1999 revealed high consumption of coca in the months preceding their deaths. Consuming the leaves was believed to induce holy trances and altered states while also disorienting the victims, making them easier to subdue.

As the powerful controlled production and distribution, access to coca was, at first, limited to the Inca elites.

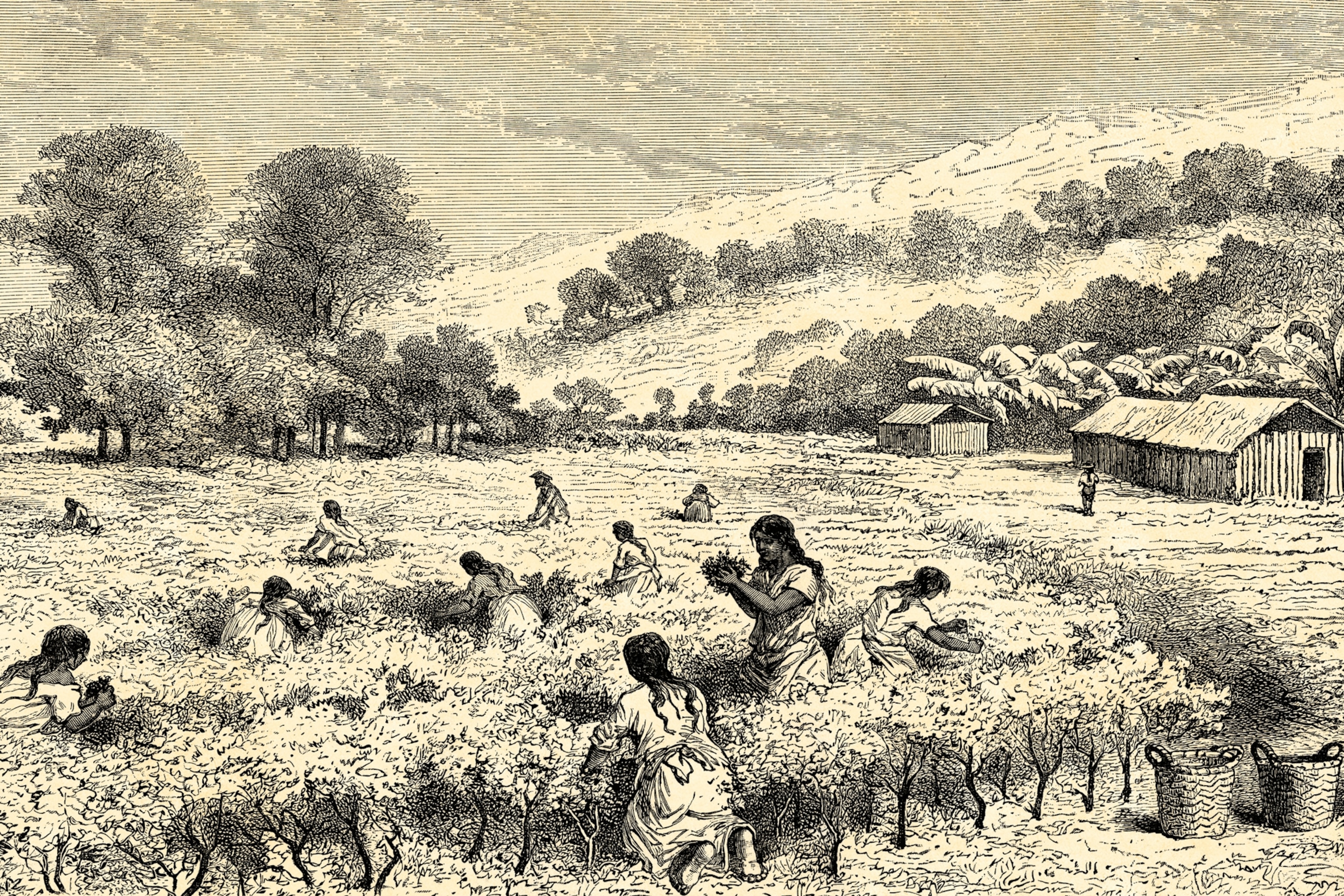

Cultivating the Crop

The Inca system for growing and harvesting coca leaves involved many steps. The plants were grown in clear-cut fields in warm, wet regions. When ready for harvesting, the leaves would tear when folded. They were picked and then laid out in thin layers to dry in the sun. Imperfectly colored leaves were rejected. Coca leaves are very fragile, and although meticulous efforts were made to ensure they kept their flat shape and uniform color, a large part of the harvest was lost during drying. The entire process required particular care to maintain as many leaves as possible.

Because of their high value, coca leaves could serve both as a commodity and a currency. Public officials and regional or local lords were paid for their services to the empire in precious metals, fine textiles, and baskets of coca leaves. The Sapa Inca—the “only Inca,” or the king—rewarded loyalty with baskets of coca leaves. They were also given out to soldiers at feasts to celebrate victories. Of all prestigious Inca goods, coca was the most highly valued. Garcilaso de la Vega, who was of Spanish-Inca parentage, wrote: “[The Inca] place it before gold and silver and precious stones.”

Because of its high value, coca was largely consumed by the imperial Inca elites. During the last days of the Inca Empire, a relaxation of restrictions on coca consumption began. Some researchers argue that this change could be due to the fact that—unlike during the empire’s earlier stages—the state could no longer guarantee the food supply for the entire population. Coca started to be used to dull hunger in lean times. Nevertheless, its association with food for the elite prevailed until the Inca Empire was conquered by the Spanish in 1532.

In the early days of the conquest, Spanish chroniclers from the 16th and 17th centuries noted how the wealthy had a monopoly on coca. Juan de Matienzo wrote that leaves “were a delicacy for lords and chiefs and not for the common people.”

After the conquest coca consumption spread among the indigenous population, as recorded by many Spanish colonists who exploited the Inca as slave labor. The Spanish authorities discovered how coca increased productivity, and encouraged the enslaved people to consume it. In time the crop became a lucrative business for Spanish landowners, who raised production to meet increased demand. The missionary Father Bernabé Cobo wrote: “It is the most profitable product in the Indies [sic] and has made many Spaniards rich.”

An Acquired Taste

The Spaniards often mocked indigenous people for their belief in the power of coca. But skepticism started to give way to interest in the strange leaf. In 1653 Father Cobo wrote that the Indians “say that [coca] gives them strength, and they feel neither thirst, hunger nor tiredness. I think it is mostly superstition, but one cannot deny that it gives them strength and breath, as they work twice as hard with it.”

Garcilaso de la Vega recorded the following conversation between two Spaniards, a gentleman and a farmhand near Cusco. The first asked, “Why do you eat coca, like the Indians do, when Spaniards find it so disgusting and detestable?” The other, who was carrying his two-year-old daughter on his back, replied. “In truth, sir, I detest it no less than anyone, but need forced me to imitate the Indians and chew it. Without it I would not be able to bear the burden. With it I have strength and vigor to be able to undertake my labors.”

Today coca leaves are harvested as an essential ingredient of the illegal, but highly lucrative, production of cocaine. Despite the plant’s role in so much violence and political instability across the Americas, its traditional use is still invoked by Andean societies as a symbol of their enduring culture.