Seeking the Hidden Temples of Cambodia

Angkor Wat—one of the most important archaeological sites of Southeast Asia—lay undercover for centuries, swallowed up by the jungle after the mighty Khmer Empire declined.

Pools of water reflect the harmony and majesty of Angkor Wat’s structures, while its five soaring towers resemble the lush forms of the green trees surrounding them. The most recognizable landmark at the Unesco World Heritage site of Angkor, the temple is regarded by many as the pinnacle of the dazzling, inventive culture that flourished in medieval Cambodia.

Built during the heyday of the Khmer dynasty in the 12th century, this extraordinary complex of Hindu and Buddhist monuments remained hidden and unknown, especially to European missionaries. It was only in 1601 that a Spanish monk, Marcelo de Ribadeneyra, compiled the experiences of missionaries, whose zeal had pushed them south from Siam (modern-day Thailand) into the thick jungle areas around the Mekong River. From there they brought back intriguing reports of “a great city in the kingdom of Cambodia” with “curiously carved walls” and huge buildings that had fallen into ruin.

These ruins were mentioned by other writers, including Gabriel Quiroga de San Antonio, who in 1604 became the first European to name one of the most distinctive of the monuments, which he referred to as “a temple with five towers called Angor [sic].”

1860

Henri Mohout writes extensively on Angkor, as France begins its colonial expansion into Cambodia.

1866

Louis Delaporte’s sketches of the Angkor temples trigger public interest in Cambodia back in France.

1878

The Exposition Universelle is held in paris. Khmer artworks exhibited there cause a sensation.

1881-82

Delaporte returns to angkor. Back in Paris, he finds a home for his collection in the Trocadéro Museum.

Lost Glory

Under constant attack by its neighbors, the Kingdom of Cambodia was in a weakened state by the 17th century. With little knowledge of the region’s history, the missionaries assumed that Angkor must have been built by another civilization.

In fact, it is now believed Cambodia was once a major world power. A 2015 survey of the site has confirmed that colossal cities once lay near Angkor, and that Cambodia could well have been the largest empire on Earth in the 12th century.

From the ninth century, under the Khmer dynasty, Cambodia built up an empire that covered swaths of what is now Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos. When the Khmer king Suryavarman II built the Angkor Wat temples in the 1100s, the empire was at the peak of its power. Angkor Wat, meaning “capital temple,” was sacred to the Hindu god Vishnu, and the complex’s architecture was greatly influenced by Indian style. In a sign of the region’s shifting religious loyalties, it was later adapted for Buddhist worship.

In the 1400s, the empire declined. The city was partly abandoned and rapidly swallowed by vegetation. Hundreds of years later, its mystery gave rise to outlandish myths among the first Europeans who saw it: Spanish missionaries attributed it to leaders like Alexander the Great, while others theorized it had been built by Jews who had passed through the region before settling in China.

The French Arrive

At first, the ruins attracted some interest among the Europeans, but they were more concerned with trade and spreading Christianity than studying the rich religious history of the region.

In the mid-19th century, French colonial expansion into the area helped spark renewed interest in the history of Cambodia, and especially in finding the “lost” temple city of Angkor. In January 1860, French naturalist Henri Mouhot reached Angkor Wat, an experience that profoundly moved him: “a rival to that of Solomon,” he wrote, “and erected by some ancient Michael Angelo [sic] ... [it] is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome.”

A year later, the explorer died prematurely in Luang Prabang in Laos, but his passion for Angkor—devoid of the Eurocentrism and prejudice of the time—fueled a growing curiosity in Cambodian culture.

Shortly after Mouhot’s death, France made Cambodia a protectorate. It was decided to open up a route to the Chinese region of Yunnan along the Mekong River, and an expedition set forth to map it.

After the French exploratory team left Saigon in 1866, it did take a detour to explore Angkor. The French spent a week mapping the buildings and documenting the ruins. Louis Delaporte, a young artist, made a set of engravings in a bid to capture the deep impression the site’s beauty made on him: “I admired the bold and grandiose design of these monuments no less than the perfect harmony of all their parts,” he wrote. “Khmer art ... is the most beautiful expression of human genius in this vast part of Asia.”

At first, Delaporte’s attempts to promote Khmer art in France were shunned. The Louvre Museum rejected the 102 crates of Cambodian antiquities. Despite this official disdain, Delaporte’s patience paid off. The display of Khmer artifacts at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878 made a powerful impression on the public; soon after, Delaporte’s collection was given a home at the Trocadéro Museum in Paris. Thanks to these displays, Khmer art became known to the rest of the Western world and inspired artists such as Paul Gauguin.

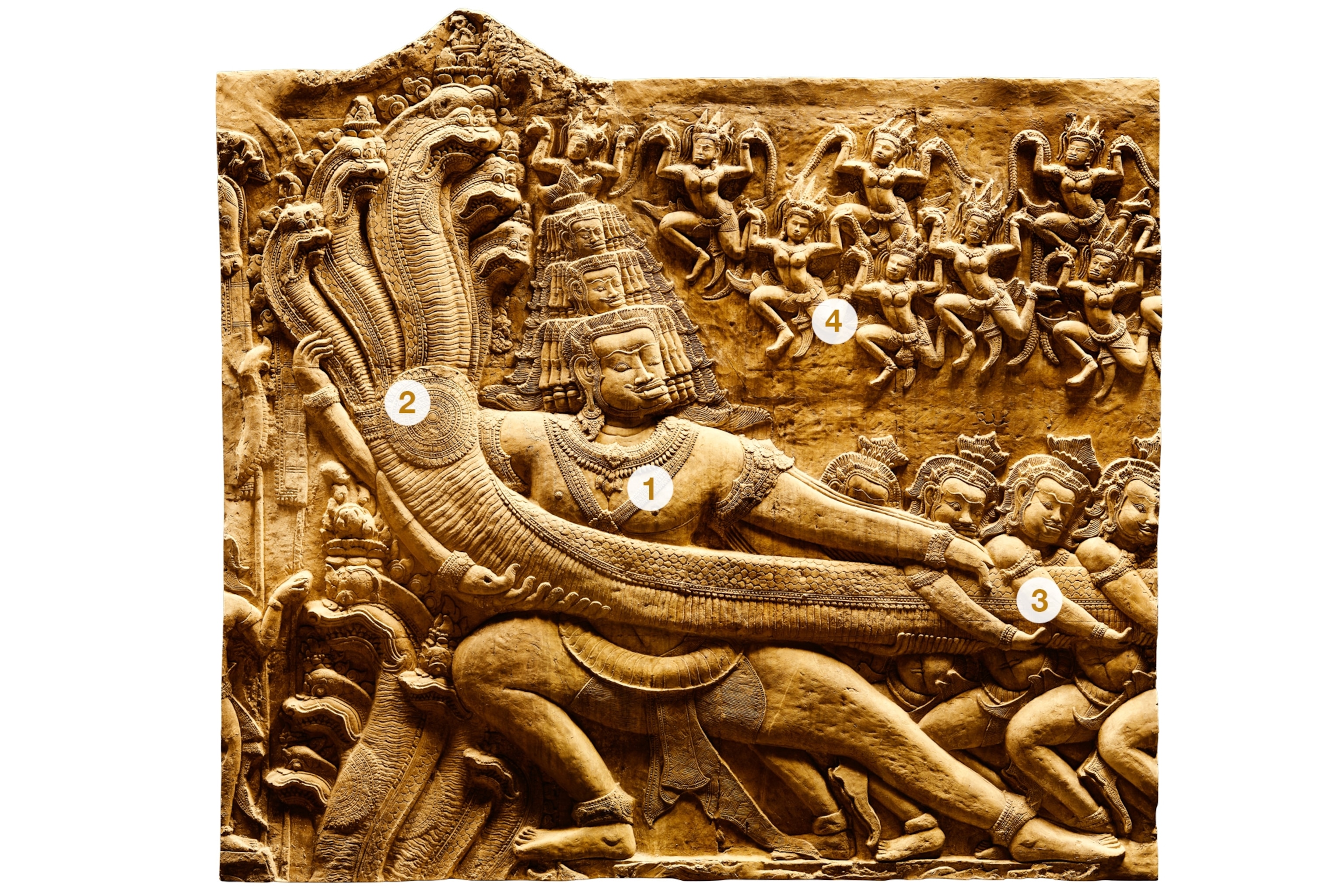

The Elixir of Life

1. Bali Maharaja, king of the demons

This detail shows the churning of the ocean of milk, in which both gods and demons must combine forces to churn up the elixir of life. At the center, Bali Maharaja directs the demons.

2. Vasuki, the five-headed snake

Elsewhere in the relief, Vishnu orders the five-headed snake to wrap itself around Mount Mandara (not shown here). Vasuki turns the mountain to churn the ocean.

3. Demon helpers

A row of Hindu demons hold Vasuki in place, under the guidance of their leader, Bali. Far to the right of this relief (not shown) the gods are also restraining Vasuki’s writhing body.

4. The divine apsaras

After thousands of years, the churning creates the nectar of immortality, the sun, the moon, and the apsaras, or celestial nymphs, whose beauty gets the better of the demons.