Machetes and sketchbooks introduced the Maya to the world

In the 1840s, John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood studied Maya civilization with the best technology the 19th century had to offer: compelling words and captivating artwork captured during a jungle expedition.

Today's archaeologists have amazing technology to guide their work in the search for the past, but in the 1830s, explorers had to rely on different methods of collecting data. Despite ruling an empire that included swathes of Central America, King Philip II of Spain never crossed the Atlantic. His insights into his New World realms came to him in the form of detailed reports, such as one penned in 1576 by Diego García de Palacio, a senior official in Yucatán:

The first place in the province of Honduras [is] called Copán; there are ruins there, with vestiges of what had once been a great population, and of magnificent buildings [including] mounds that seem to have been made by hand, and in them many things to note. Before reaching them, there is a large figure of an eagle in stone . . . containing certain letters of a language unknown.

In 1839 two archaeologists, John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood, carefully pored over these words to Philip to help them in their journey to Copán. Although it, and other sites, were not exactly “lost,” a fog of ignorance still obscured European and American notions of Mesoamerican culture. Some early 19th-century authors—guided by racist assumptions about the indigenous inhabitants of the area—even argued the monumental ruined cities of Central America must have been built by Egyptians. Aided by the scant documentation on the site, including García de Palacio’s letter, Stephens and Catherwood set out to change these opinions and reawaken interest in these ceremonial centers, now swallowed by the jungle. (See also: Exclusive: Laser Scans Reveal Maya "Megalopolis" Below Guatemalan Jungle)

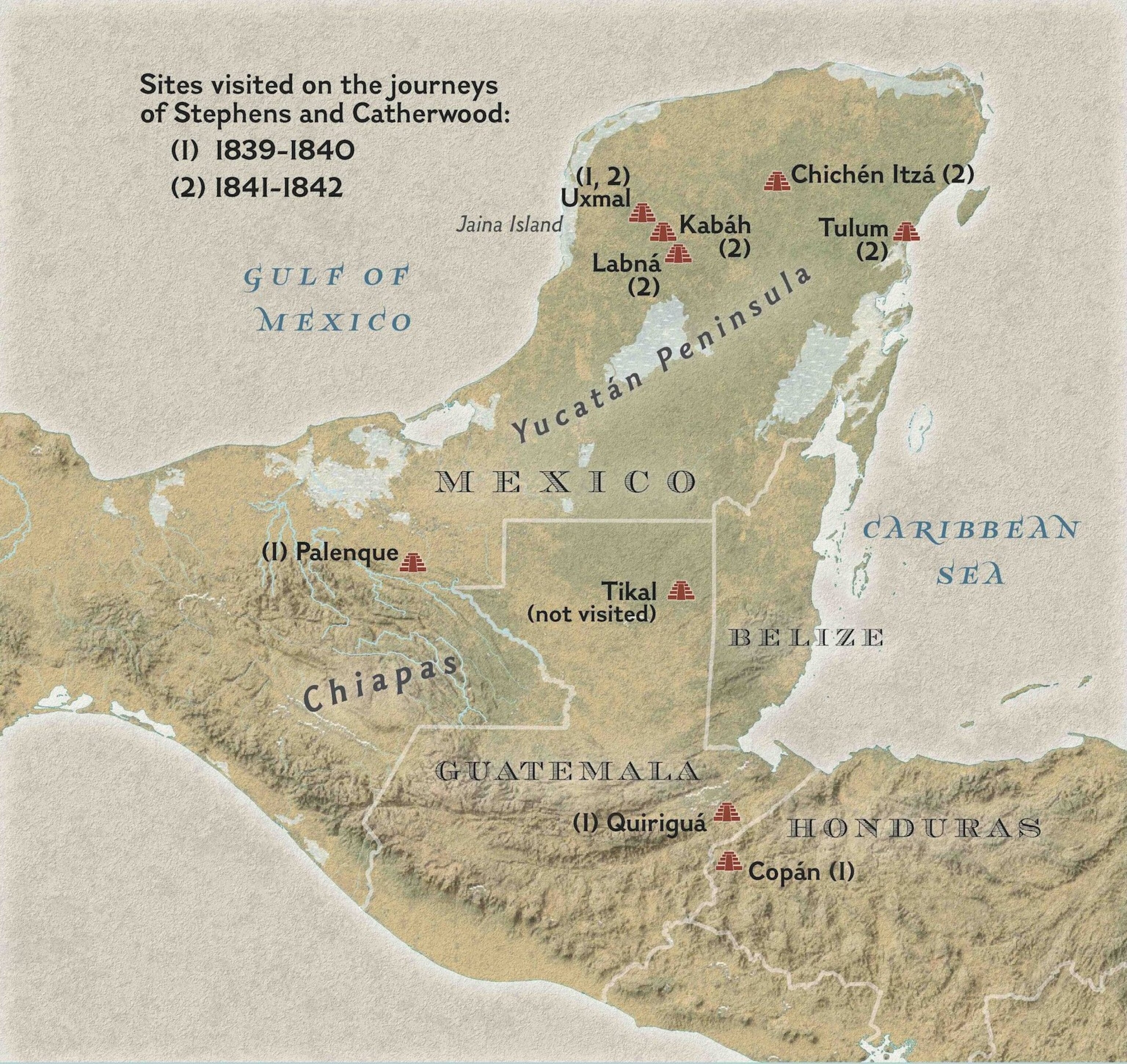

Equipped with basic surveying gear and machetes, they embarked on two adventure-filled tours of Central America between 1839 and 1842 that provided the first in-depth surveys of the sites. Lavishly illustrated by Catherwood, their books revealed to the world the scope and complexity of the Maya’s ceremonial centers, which flourished in that culture’s classical age, between the third and 10th centuries A.D.

Perfect Partnership

John Lloyd Stephens grew up in New York. After studying law, he entered the ranks of the Democratic Party, and looked set on a career in politics. But his life took a radical turn when his doctor recommended that a trip to Europe might help him recover from a respiratory condition. Not content with the usual sightseeing in Italy and Greece, he ventured into Turkey.

In November 1835, unable to secure a return passage to the United States, Stephens took advantage of the delay in returning to explore the Middle East. Adopting the pseudonym Abdel Hassis, and paying the sheik of the region, he was granted access to visit the Nabataean city of Petra. Befriending those in power would set Stephens in good stead for much of his traveling career: In Egypt he took in the key sites thanks to the safe passage afforded him by Mehmet Ali, the Ottoman governor of Egypt.

Stephens also knew how to turn his experiences into good copy, relating his wanderings in the Middle East and Europe in two volumes in 1837 and 1838. At around the time he was writing these works—which proved to be a major commercial success—Stephens got to know Frederick Catherwood in London. A gifted linguist, who spoke and read Arabic, Italian, Greek, and Hebrew perfectly, Catherwood was also a talented architect, artist, and draftsman, and had already taken part in several archaeological expeditions. The two men formed an instant bond, and went on to become inseparable intellectual and traveling companions.

On his return home, Stephens was appointed by President Martin Van Buren as ambassador to the Federal Republic of Central America. Comprising modern-day Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, this short-lived republic was fragmenting due to a civil war. In an era that took a more relaxed attitude to official duties than today, Stephens had no intention of totally giving himself over to his diplomatic duties. Fascinated for many years by Mesoamerican culture, he planned to use his position to investigate the archaeological remains in the region.

This was not entirely virgin territory. The great German anthropologist Alexander von Humboldt had written on ruined Central American cities following his expeditions in the early 1800s. The soldier and explorer Juan Galindo had examined and drawn Palenque and Copán in the 1830s. As a result of this study, Galindo had drawn tentative conclusions as to their both forming part of a shared culture.

Stephens avidly read these, and as many other sources on the sites, as he could. Flush with funds from his books on the Middle East, and realizing that Catherwood’s visual skills would add luster to his chronicles, Stephens brought his British friend on board as illustrator. In October 1839 the pair left New York by ship for Belize.

Jewels of the Rain Forest

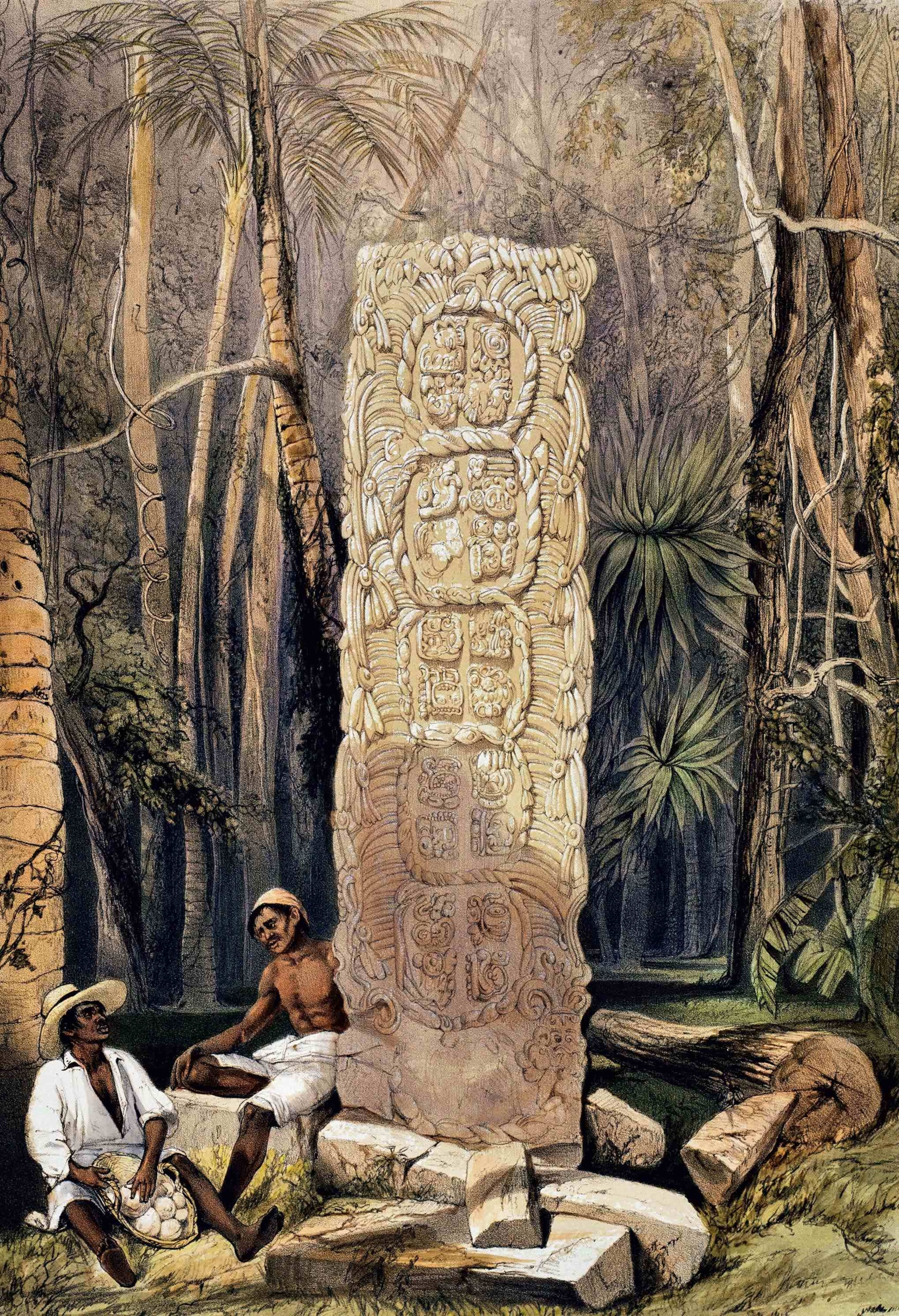

To arrive at their first site, Copán in modern-day Honduras, they had to slog through large mud patches and endure high humidity, searing heat, and biting insects as they hacked their way through the dense vegetation with machetes. When they at last reached Copán and glimpsed its magnificent pyramids, so different from those they had seen in Egypt, they were ecstatic. They found intricate stelae and engravings that convinced them the city had been home to an advanced indigenous civilization.

At first the owner of the land wanted them to leave. But Stephens donned his ambassador’s coat “with a profusion of large eagle buttons,” and used his credentials to convince the owner to give them permission to draw and study the ruins for $50. The two men got to work, Stephens directing the excavation. Catherwood, equipped with his theodolite—an instrument for measuring angles—drew up a plan of the city. He made extraordinarily detailed drawings, aided by a camera lucida, an early 19th-century invention that projects highly detailed images of objects onto a flat surface, which can then be traced.

Having visited Quiriguá, another Maya site nearby, and seen its important collection of stelae, the explorers set off for Palenque. On the way, they noted the stunning beauty of the landscape of Guatemala, and finally reached the border of the Mexican state of Chiapas.

There, they discovered that General Santa Anna, president of Mexico, had ordered that nobody visit the city. Ignoring the prohibition, the pair continued their arduous journey and finally reached their goal. Soaked after crossing the water course that divided the settlement, and eaten alive by mosquitoes, they first saw the ruins poking out above the canopy of trees. Despite the prohibition to enter, they set up camp, installing themselves inside one of the buildings known as the Palace. One of their first tasks was to strip the vegetation from the site’s structures.

The great stone bas-reliefs of Palenque’s main courtyard were immortalized in Catherwood’s meticulous drawings. He also made engravings of the Temple of the Foliated Cross, the Temple of the Sun, and the Temple of the Inscriptions. It was in the latter a century later that the tomb of Pacal the Great, Lord of Palenque, would be located, whose reign coincided with the city’s seventh-century golden age. Stephens documented common features between this and the other Maya sites he had seen, and argued that many of the reliefs they had found bore what he believed to be complex hieroglyphics forming part of a narrative. Stephens’s hieroglyphs theory was based only on intuition at that stage, as breakthroughs in deciphering Maya writing did not come until the late 20th century.

Not all of Stephens’s methods would be considered so praiseworthy by today’s standards. He tried, for instance, to buy Palenque outright. Mexican law, however, did not permit a foreigner to own land unless he was married to a Mexican—a step Stephens was not prepared to take. His grandiose ambition had been to transfer the monuments of Palenque, and other sites, stone by stone, and re-create them in New York in a museum dedicated to Maya culture. He no doubt considered his aims honorable, but such an act would today be unthinkable.

After almost two months of work, the two men struck camp, setting off for the Gulf of Mexico, determined to explore the ancient city of Uxmal, whose magnificent Pyramid of the Magician is regarded as one of the jewels of the Puuc style of Classic Maya architecture. By the time they arrived there, on June 24, 1840, Catherwood was gravely ill with malaria, and soon after, they returned to New York so that he could recover.

Adventurers and Authors

Despite its hardships and its conclusion in illness, this first trip was deemed a great success. In New York Stephens put all his notes in order and published a new book, entitled Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán, which would also prove to be another publishing hit. In it, detailed archaeological accounts rub shoulders with descriptions of a country torn apart by war and instability, with tales of bandits roaming the country. Amid the turmoil and discomfort, Stephens found time to sketch the people he met, and revels in quirky, colorful details, such as detailing the clutter of a priest’s room, encumbered with: “a cruet of mustard and another of oil . . . cups, plates, a sauce-boat, a large lump of sugar, skulls, bones, books, cheese, and manuscripts.”

Once Catherwood had recovered, the pair planned for another journey to Yucatán. Despite his air of a flamboyant adventurer, Stephens was a meticulous organizer, and prepared for the second trip in minute detail. Leaving in October 1841, they were accompanied by the naturalist Samuel Cabot, who wanted to study the local fauna. Among other sites, the team explored the cities of Kabáh, Chichén Itzá, and Labná, and revisited sites from their earlier visit, including Uxmal. A second book, entitled Incidents of Travel in Yucatán, containing 120 engravings by Catherwood, was published in two volumes in New York in 1843. A year later, Catherwood published a stand-alone work containing a selection of his color lithographs of the sites.

The two men never traveled together again. Stephens joined the board of the Ocean Steam Navigation Company, and in 1850 he was offered a chance to participate in the construction of the Panama railway. Although he died in 1852 in New York, a romantic legend emerged that he had met his end in Panama in the shade of a ceiba tree, sacred to the Maya. In 1947 Maya hieroglyphs were added to his gravestone, recognizing his contribution to the study of Maya civilization.

Frederick Catherwood died under tragic circumstances in September 1854, when the paddle steamer on which he was traveling was wrecked, and he perished alongside some 350 others. The death of the man whose artwork had immortalized the rediscovered Maya cities passed almost unnoticed by public opinion of the time.

Isabel Bueno is an honorary member of the Vicente Lombardo Toledano Center in Mexico, on whose culture and history she has written extensively.