Who was Jack the Ripper?

Facing down a hundred-year-old mystery, relentless detectives continue to search for the identity of the infamous killer, who terrorized the women of Whitechapel in autumn 1888.

At the end of the 19th century a foreign traveler only had to spend a day sightseeing in London to feel stirred by England’s power. At Westminster the Houses of Parliament proudly proclaimed British global domination, while at Buckingham Palace Queen Victoria crowned the nation’s golden age. All along the Thames to the sea, lined with ship after ship of merchants and the Royal Navy, visitors could see for themselves the formidable maritime might of the largest empire the world had ever known.

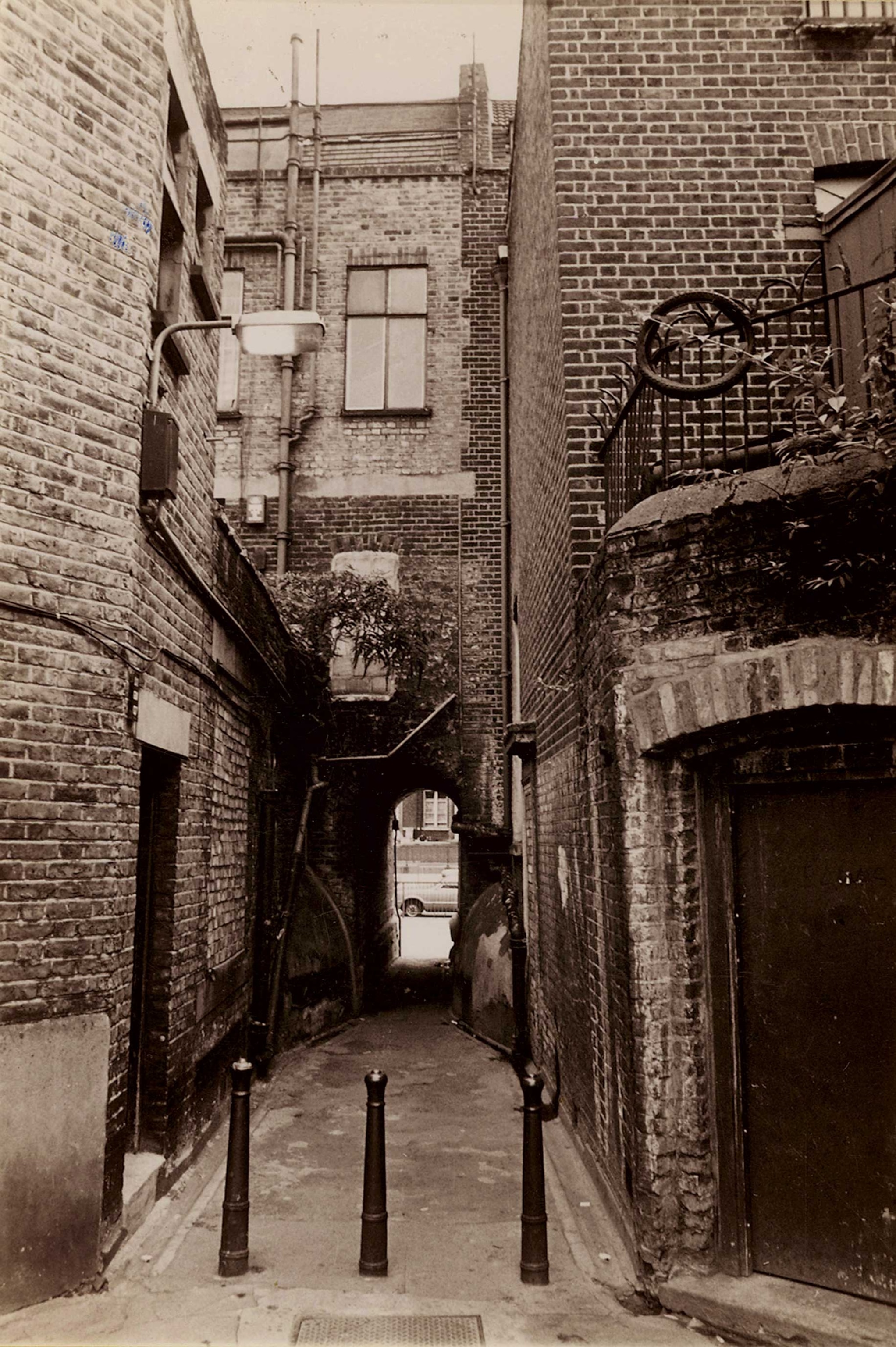

But all was not well with London. Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novel, Heart of Darkness, describes London as “one of the dark places of the earth.” To the theatergoers and shoppers thronging the well-lit, opulent streets of the West End, this description might have seemed out of place, but just three miles to the east, in the neighborhood of Whitechapel, disease, alcoholism, and poverty ravaged the lives of thousands of souls. It was a place that was, as the Diocese of London reported, “as unexplored as Timbuktu.”

The mystery of Jack the Ripper began on August 31, 1888, when the body of a dead woman was found in a Whitechapel street. Her throat had been cut and her abdomen gouged open. Three months later, when what became known as the “Autumn of Terror” had ended, four more women had undergone the same grisly fate.

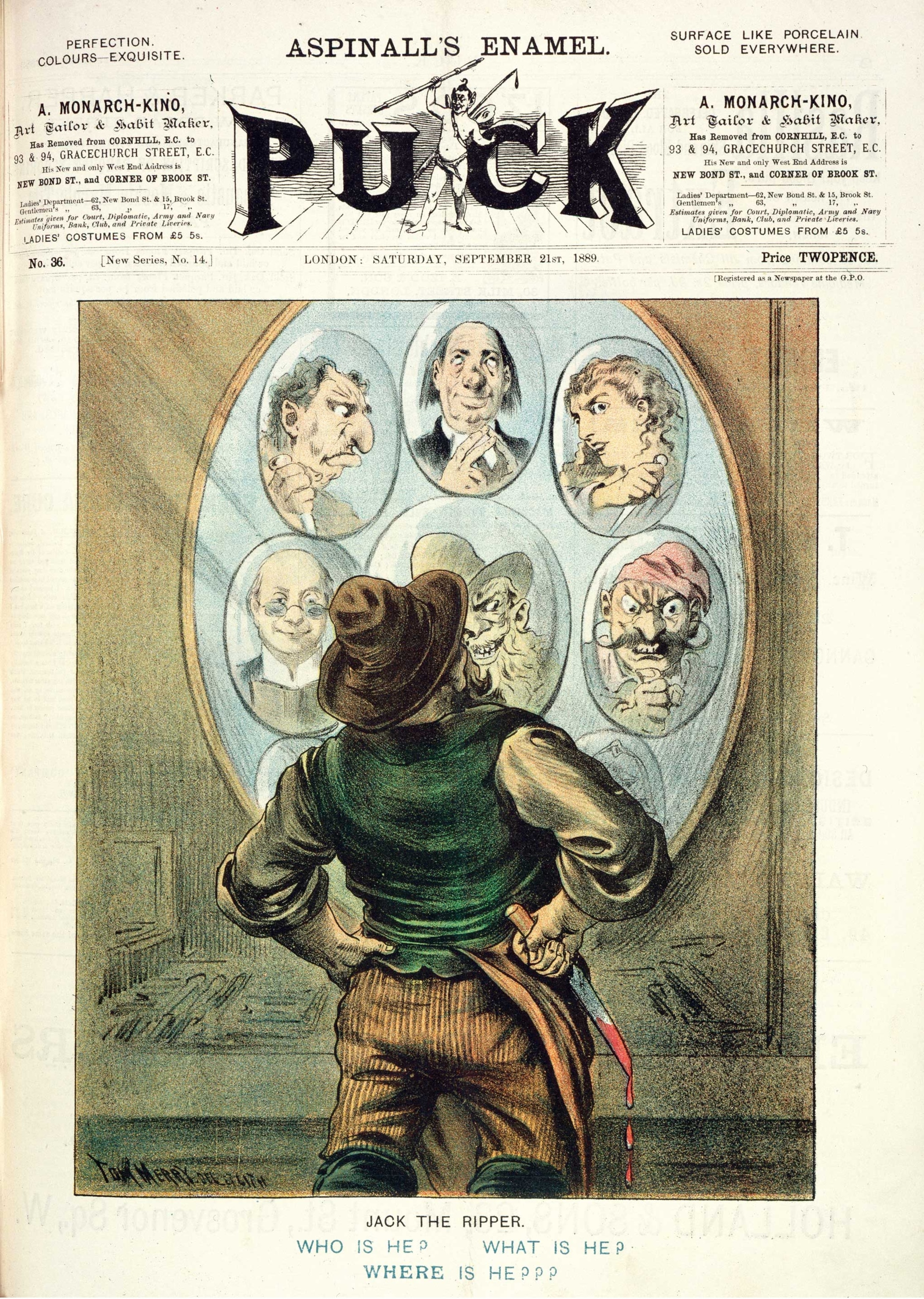

The killings electrified England. Wealthy Londoners were suddenly forced to take notice of a dangerous world located at home in their midst. As the hunt for the unidentified killer dragged on, well-to-do Victorian society, from Queen Victoria down, grew obsessed by the case. In the city Jack the Ripper became a stand-in for the prejudices and fears of London society. Anti-Semites used the murderer to defame the Jews of the East End; the poor blamed the rich and the rich blamed the poor; the terrible fate of the five dead women became fodder for the burgeoning sensationalist press, while social activists seized on the case to clamor for relief from urban poverty.

Above all, the Ripper case laid bare an uncomfortable irony: At the heart of a city that prided itself on spreading Pax Britannica around the world, a murderer walked free—and none of the authorities could stop him.

When the murders abruptly ceased in November 1888, the mystery only deepened and grew. Nearly 140 years later, Jack the Ripper has become arguably the most infamous and most mythologized serial killer. (See also: The World's Oldest Murder Mystery was 430,000 Years in the Making.)

The Murders

In the late 19th century, life for lower-class women in London was difficult. Many of them worked for meager wages as domestic servants or in sweatshops. Their daily wages often meant they would have a place to sleep at night: Three or four pence would buy a bed in one of Whitechapel’s many lodging houses. In desperation, women could turn to prostitution, and certain streets of London’s East End became notorious destinations for the sex trade, of which the Ripper’s victims had all been working at the time of their deaths.

When Jack the Ripper was terrorizing Whitechapel, other killers were at work as well. Collectively known as the “Whitechapel Murders,” the violent deaths of 11 women revealed the dangers facing lower-class women at the time. Of these murders, most experts agree that Jack the Ripper was responsible for the five that occurred from August through November 1888.

Discovered in the early morning hours of August 31, Mary Ann Nichols, also known as Polly, was a 43-year-old mother of five and the first confirmed victim of Jack the Ripper. The daughter of a blacksmith, she spent much of her youth in various poorhouses of the capital. Abandoned by her husband, she earned a living through workhouses, prostitution, and petty theft. Like many women of her class, her name might have been lost to time—had she not been murdered that August night.

One week later, Annie Chapman, a 47-year-old widow and mother, was discovered on September 8 shortly before 6 a.m. in a yard on Hanbury Street. Her injuries appeared similar to Nichols’s, but she was missing some of her internal organs. At the end of the month, the killer would claim two more lives in one night: Elizabeth Stride, age 45, and Catherine Eddowes, age 46. The last official victim met her death on November 9, 1888: The body of 25-year-old Mary Jane Kelly was discovered brutally mutilated in a lodging house in Miller’s Court. All residents of Whitechapel, these women lived in poverty, which left them vulnerable to the predator prowling the streets.

The Investigation

From the beginning of the investigation, Scotland Yard was flummoxed. The only thing known for sure about Jack the Ripper—assuming, as most theorists do, that he acted alone—is that he killed women. According to Edmund Reid, one of the detectives assigned to investigate the case, these were the only facts: The five women were all active or former prostitutes; all of the victims were from the lower class; all lived no more than a quarter of a mile from one another; and all the murders were committed after pub closing time.

To Reid’s key facts can be added another salient detail: No one ever heard a single scream or cry for help, unusual for such a densely populated neighborhood. None of the bodies exhibited defense wounds, such as slashes or bruising on the hands and forearms. The one solid, reported sighting of the killer was on the early morning of September 8, 1888, when a woman saw Annie Chapman, accompanied by a “foreigner” of medium height, wrapped in a dark cloak. They are believed to have met just after 5:30 a.m., and her body was found half an hour later. Like all of his other victims, there were no signs of resistance, and no one heard her cry out.

The other aspect that all the cases had in common was, of course, the killer’s use of a knife and his customary pattern of not only killing the women but defiling their dead bodies. At least three of his victims were found with internal organs removed, a detail that drove the sensationalist press of the day into a frenzy. A wave of panic spread across the whole East End of London.

Public fascination spiked after September 27, 1888, when both the Central News Agency and the police received a letter claiming to be from the killer. He taunted them for pursuing false leads and vowed in a broad London English: “I am down on whores and I shan’t quit ripping them till I do get buckled.” Three days later, the mutilated bodies of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes were found.

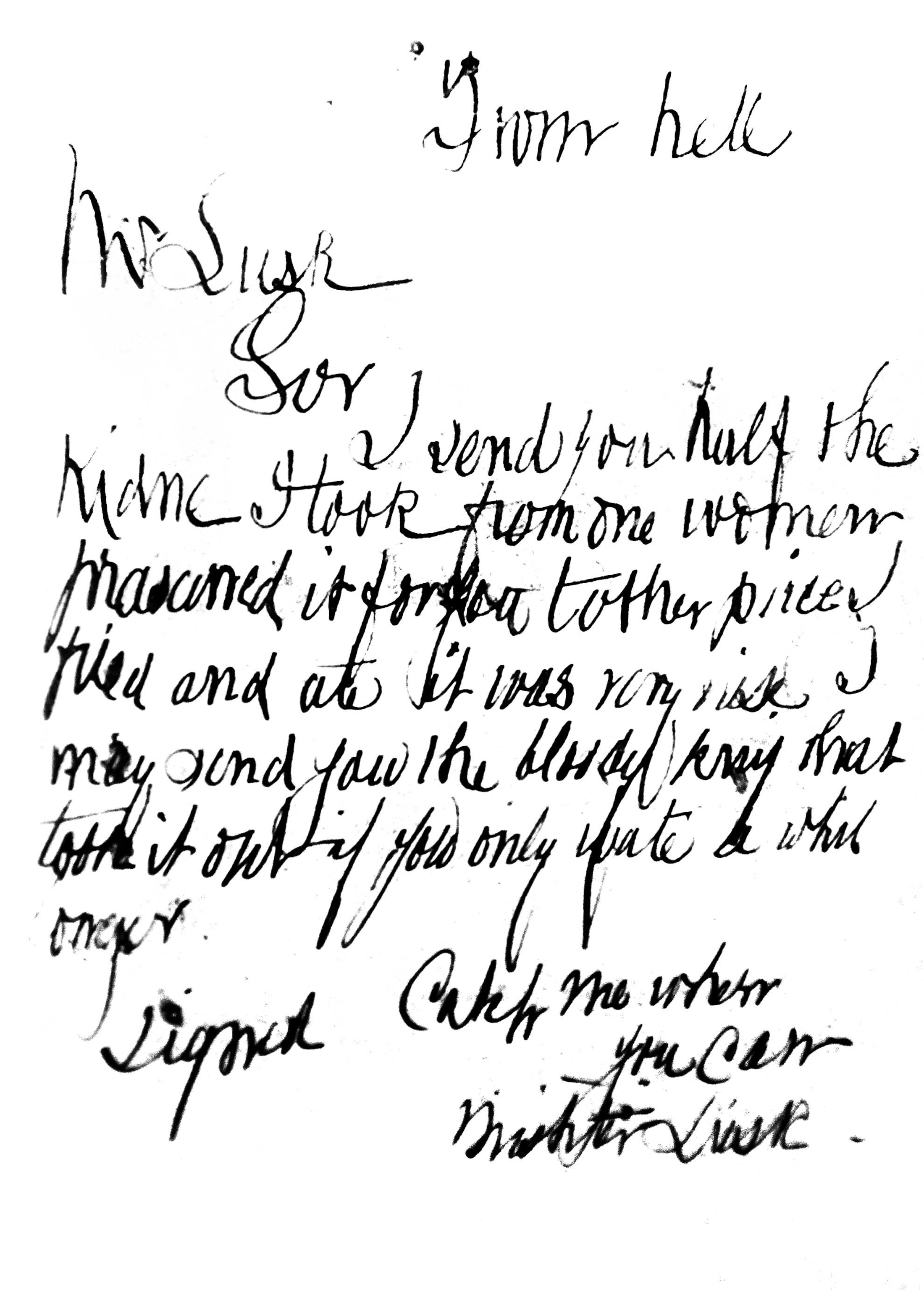

Many believe this letter is a hoax, but its signature, “Jack the Ripper,” gave the unknown killer his moniker. Hundreds of other letters followed, most of which were confirmed hoaxes. A few seemed genuine, including an October missive—datelined “from hell”—with which was enclosed a human kidney, supposedly from one of the victims.

Following the discovery of the body of Mary Jane Kelly in November, physician Thomas Bond was invited to perform an autopsy on her remains. His report makes for stomach-churning reading, even today. In the course of his grim task, Bond noted similarities with the four previous deaths. The murderer slashed the victim’s throat from one side to the other and then cut open the abdominal cavity. A theory mulled by the police was that the Ripper was a physician or even a surgeon, but Bond—who knew a thing or two about incisions—dismissed this: True to his nickname, the murderer was no precise cutter, and lacked “even the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer.”

Bond also attempted to understand the psychology of the killer, an early exercise in criminal profiling. It was not enough for the Ripper to kill, he deduced: He also had to inflict excessive violence to the bodies afterward: “The murderer must have been a man of physical strength and of great coolness and daring.” Even so, he concluded, he “is quite likely to be a quiet, inoffensive looking man probably middle-aged and neatly and respectably dressed.”

The Suspects

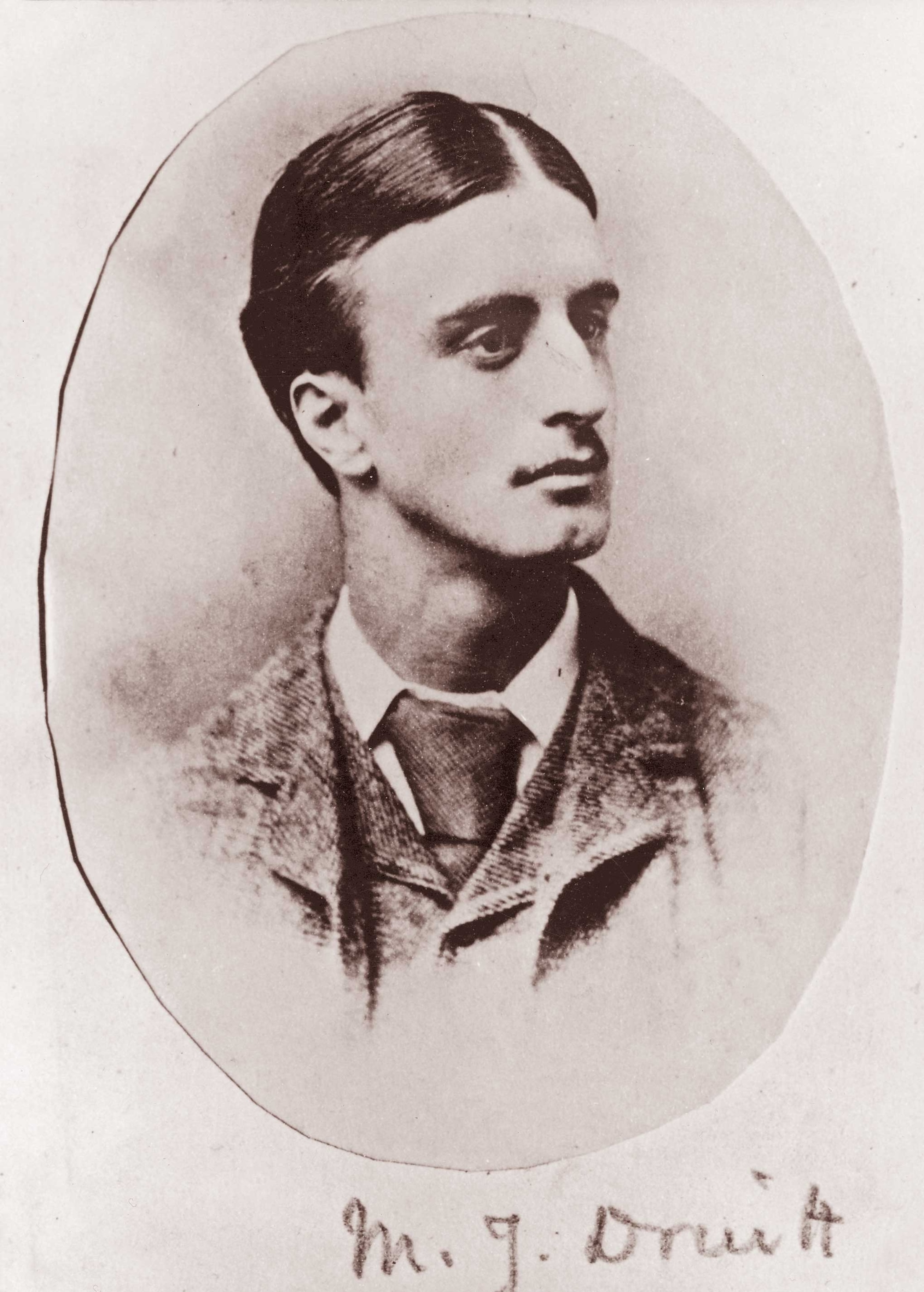

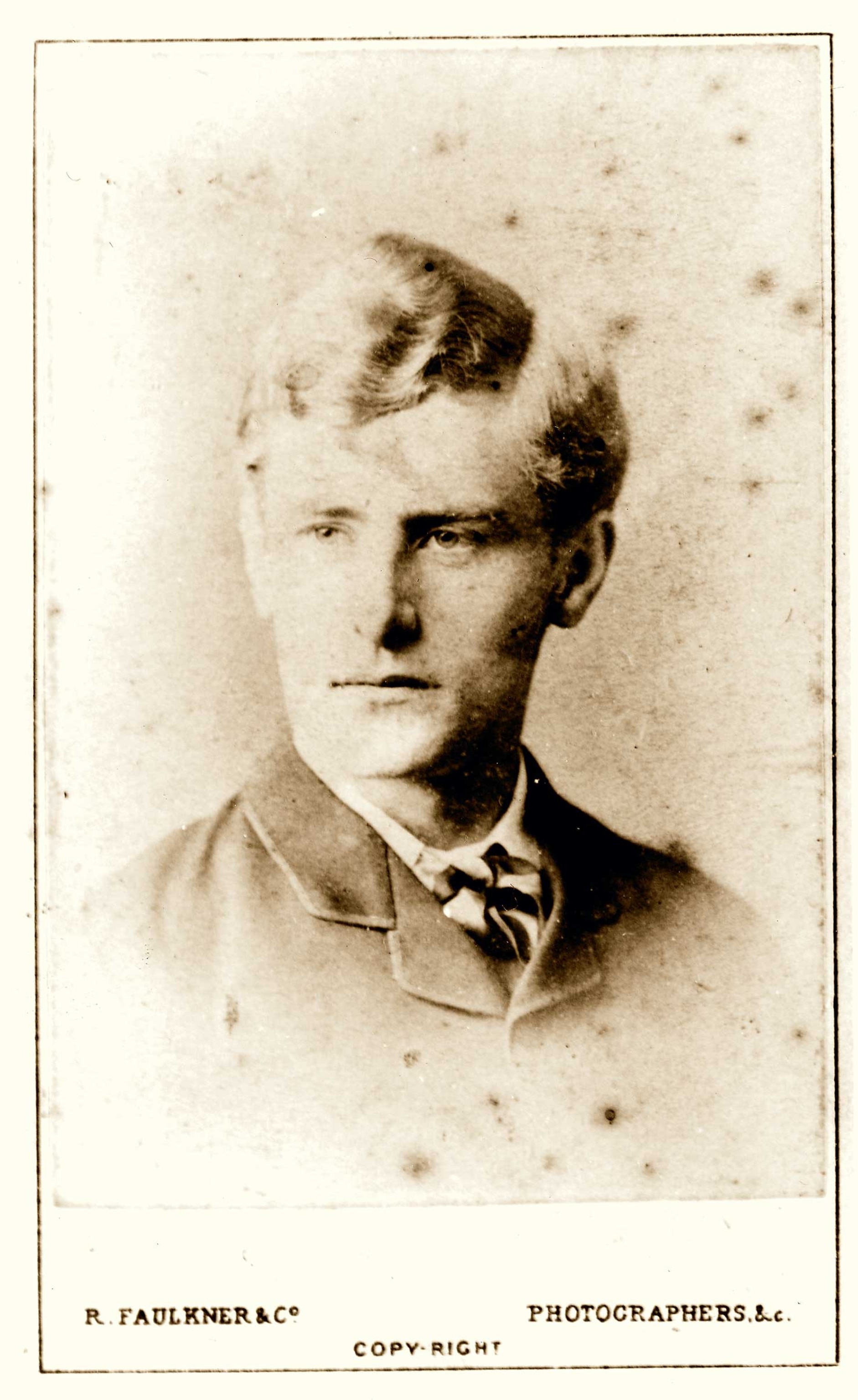

Whitechapel’s closeness to the London docks led the police to think the killer might have been a sailor passing through or perhaps a stevedore. At the time of the murders, the police investigation centered on local characters. Among these were Aaron Kosminski and John “Jack” Pizer, both working-class men. Francis Tumblety was an American-born quack doctor who possessed a collection of human organs and, it was reported, detested prostitutes. Montague John Druitt, who was from a wealthy background but had fallen on hard times, was regarded as sexually deviant. Seweryn Klosowski was a known poisoner, but not, so far as anyone knew, a stabber and mutilator. Unrelated to this police inquiry was the career of another poisoner, Thomas Neill Cream, who killed young prostitutes in the nearby borough of Lambeth by giving them strychnine-laced drinks. On being hung, he is said to have cried out, “I am Jack the—” This is highly unlikely, as at the time of the Ripper murders, Cream was in the United States, being held near Chicago in a Joliet jail.

The savagery of the killings prompted conclusions that only the feared “other” could perpetrate such wickedness, leading to a slew of prejudiced accusations against people of different ethnicities and traditions. The fact that Whitechapel was home to many Jews—and that two of the early suspects, Pizer and Kosminski, were Jews—fueled anti-Semitic feelings at the time. Pizer was suspected of being an unidentified and malevolent prowler, nicknamed Leather Apron by the press. The media characterized this figure as Jewish, with one article noting that local women “are united in the belief that he is a Jew or of Jewish parentage.”

Following the murder of Catherine Eddowes on September 30, police found a message scrawled in chalk above where her bloodstained apron was found. There are various versions recorded by the police as to what exactly was written there. One of the variants was: “The Juwes [sic] are the men that Will not be Blamed for nothing.” Many theories have been put forward to explain these words, but no photograph of them exists—the police erased the message soon after discovering it, so as to prevent anti-Semitic riots.

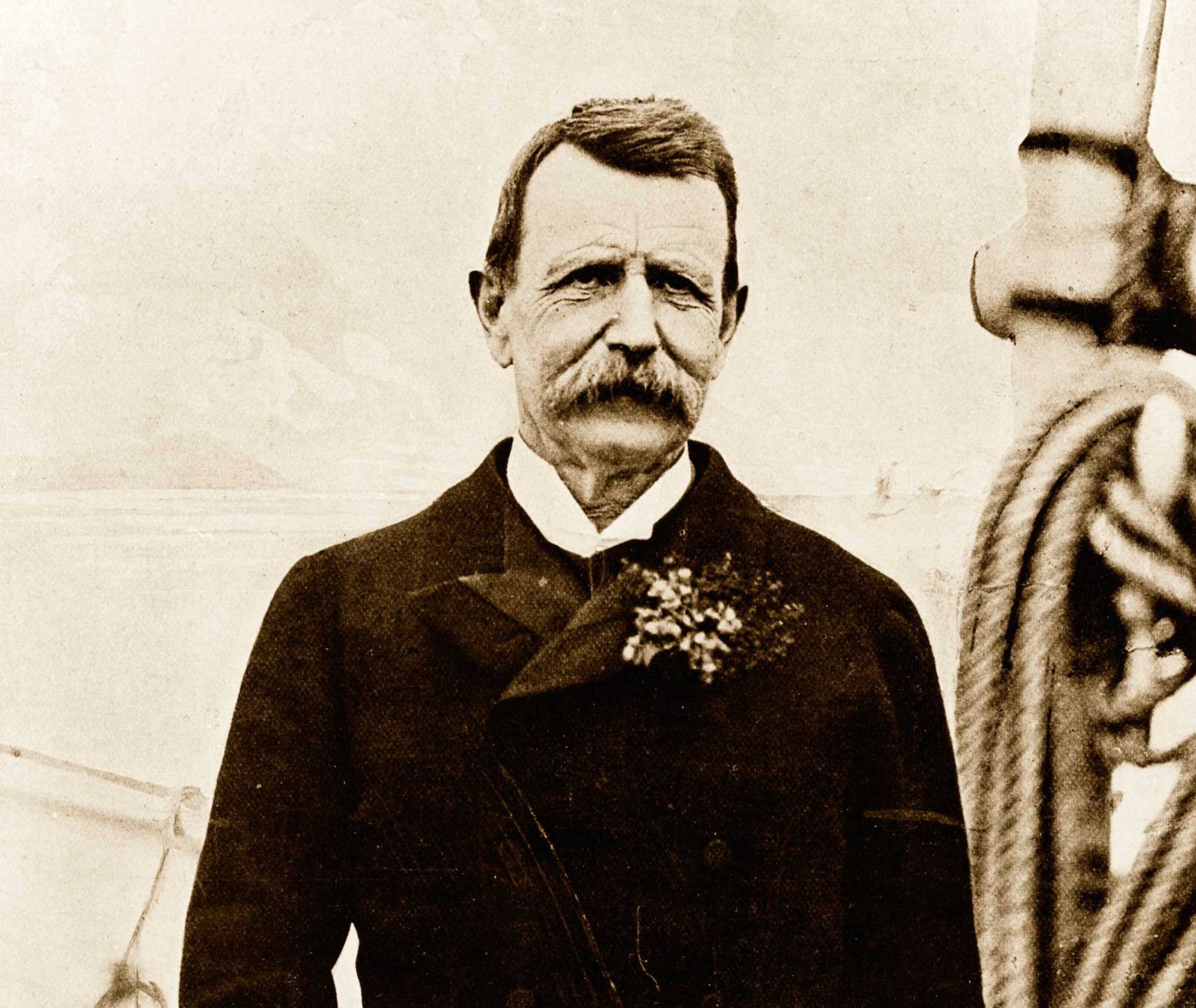

The cases against the early suspects fell apart, either because of a lack of evidence or because suspects had solid alibis. The police force came under increasing attack in the press, eventually leading to the resignation of the Scotland Yard chief, Sir Charles Warren. The new lead investigator, Melville Macnaghten, was popular with the public, but even he did not solve the crime.

The Sixth Victim

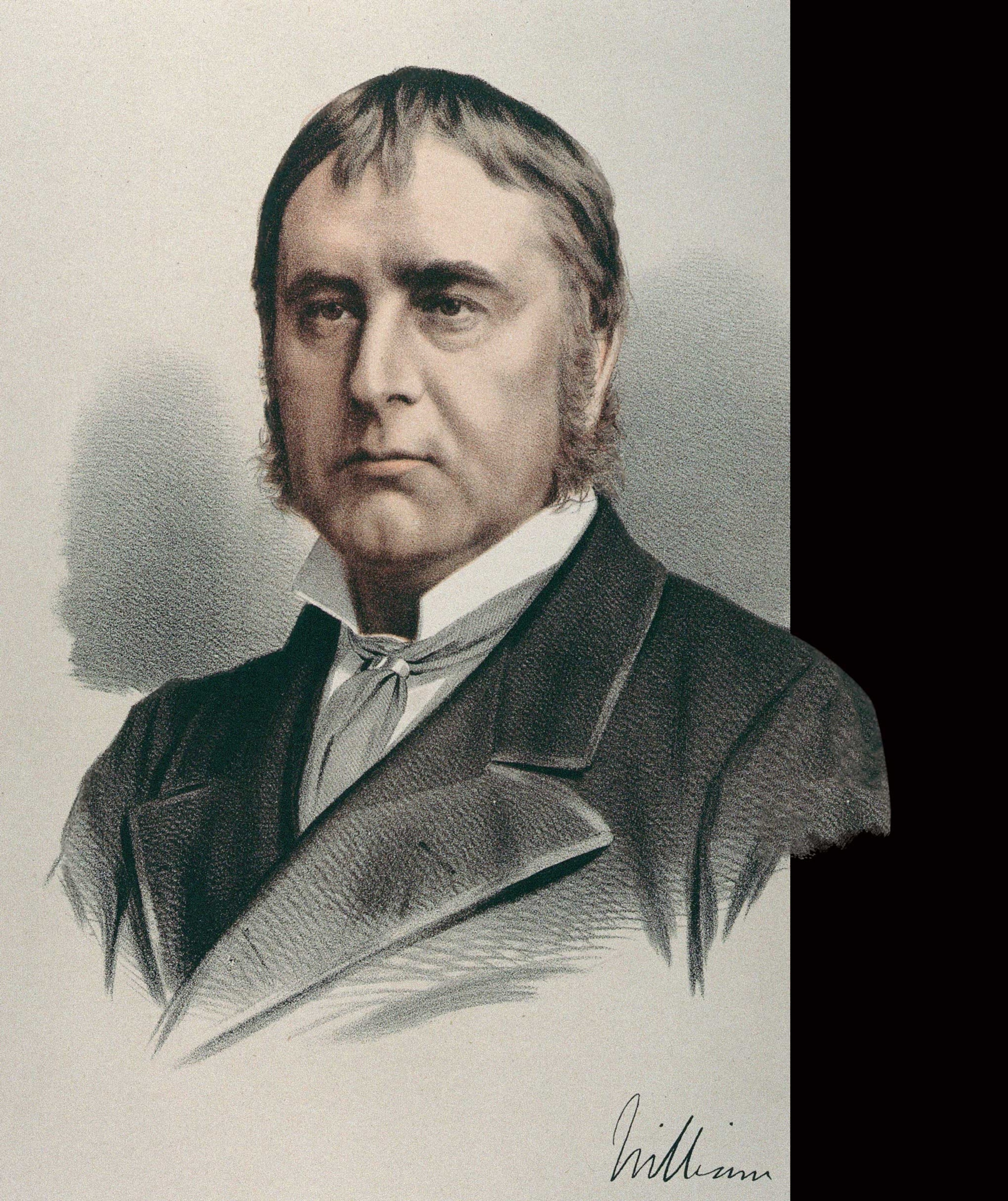

It is the stuff of movie plots, and every police chief’s nightmare: A killer is on the loose, panic is spreading, and the killer appears to be mocking his pursuers. Captained by Sir Charles Warren (above), London’s Metropolitan Police struggled from the moment Mary Ann Nichols’s body was found on August 31, 1888. As the murders mounted, and the cases against suspects fell apart, the press picked over the police’s perceived failures: They were slow to react to the murders; they took too few photographs; they destroyed evidence. Today sympathetic historians highlight the challenge of even basic policing in the East End, as well as the flow of misinformation, and suspected hoax letters, produced by the press. But the media were merciless: In October 1888 the Cork Examiner reported “people are asking whether Warren is a criminal or an imbecile?” In November, one day before the murder of Mary Ann Kelly, Warren resigned, a decision greeted by cheers in the House of Commons.

Theories and Notions

As the Ripper case remained open, an industry sprung up around it. Jack the Ripper has been the subject of more than a hundred nonfiction books, dozens of novels, several television series, and more than 20 films. The mystery has even given birth to an entire discipline known as “Ripperology,” which specializes in exhaustive research about the case and theories behind the murders.

Ripperologists have assembled a varied line-up of suspects, which seems to keep growing. Ranging from members of the royal family to the humblest Whitechapel resident, the variety of suspects is staggering: William Gladstone, British prime minister; a relative of Winston Churchill; and the English painter Walter Sickert—even though no credible evidence has ever been produced to substantiate these claims.

Another theory, adapting the plot of Edgar Allan Poe’s seminal 1841 short story, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” postulated that the Ripper was not a man but an ape who had escaped from the zoo. Perhaps one of the most outlandish ideas points the finger at Charles Dodgson, better known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll and author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. A 1996 book claimed that unscrambled anagrams in his books revealed the killings, an argument that has since been dismantled by historians.

Some have suggested wealthy doctors as suspects, including Sir William W. Gull, Queen Victoria’s personal physician. Others point to Alexander Pedachenko, an agent of Russia’s tzarist secret police, who supposedly committed the crimes to stain Scotland Yard’s reputation. The plot is detailed in a later document, now lost, written by none other than Rasputin. More recent suspects include American serial killer H. H. Holmes. Notorious for several gruesome murders during the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, it is also claimed he was Jack the Ripper. The only thing these diverse hypotheses have in common is this: None have been convincing enough to achieve the consensus necessary to close the case for good. (See also: London's "Horror Hotel" Inspired by H. H. Holmes.)

Rich and Poor

The carnage of the Ripper murders did result in some positive social change. Contempt for the lower classes was ingrained in upper-class thinking. Instead of seeing prostitution as a consequence of poverty, many better-off Londoners saw these women’s decisions as a question of morality and not a question of survival. They subscribed to a prevailing idea that many at the bottom of the social heap lived the way they did because of bad character. By the time of the Ripper murders, social Darwinism—the application of Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection to human groups—reinforced this idea.

Little by little, however, the consensus shifted toward tackling the roots of poverty. Founded in Whitechapel in the 1860s, the Salvation Army was already helping prostitutes, and attempting to wean people off the alcohol that had so blighted the lives of the Ripper’s victims. Shaken by the conditions exposed by the Whitechapel murders, conservatives also started calling for reform, motivated partly by enlightened self-interest: Improving conditions would lessen the chances of social revolt.

The murders also prompted socialists to call for meaningful reform. One memorably fiery response to the Ripper case was penned by George Bernard Shaw, who later shot to fame for his satirical play Pygmalion, the basis for the hit musical My Fair Lady. In September 1888 Shaw wrote in the Star newspaper that the Whitechapel murders had forced the wealthy to admit their mistreatment of the poor. With a sardonic twist, Shaw opined that the murderer was doing more to advance the cause of reform than years of political agitation had: “Allow me to make a comment on the success of the Whitechapel murderer in calling attention for a moment to the social question . . . The one argument that touches your lady and gentleman, is the knife.”