What's inside Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks?

Packed with intricate sketches and detailed notes, Leonardo's personal diaries reveal his countless passions—from the structures of human anatomy to the possibilities of human flight.

Leonardo da Vinci may be best remembered as an artist, with his enigmatic “Mona Lisa” and his fresco “The Last Supper” ranking among the world’s most famous paintings. But, going by the numbers, art may be the least of his contributions to the world: He has only 22 paintings on display around the world and a few hundred other personal drawings. Instead this true-to-form Renaissance man, who lived at the height of the Italian Renaissance—the late 15th and early 16th centuries when art and architecture flourished—excelled at a whopping number of subjects, from architecture to science to mathematics to engineering.

(Lost Leonardo da Vinci Mural Behind False Wall?)

His notebooks are filled with original scientific observations, speculations, and hypotheses, most of which would be born out and supported by independent researchers in the coming centuries. He sketched designs for countless engines and machines, many of which would later make an actual appearance in the world. The seeds of Western science and technology, which germinated and flowered in the scientific revolution, were planted in the Italian Renaissance, and no one sowed more of those seeds than Leonardo.

Here is a peek into some of the genius’s notebooks, showcasing his forward-thinking insights, observations, and discoveries.

(Why Leonardo da Vinci’s brilliance endures, 500 years after his death.)

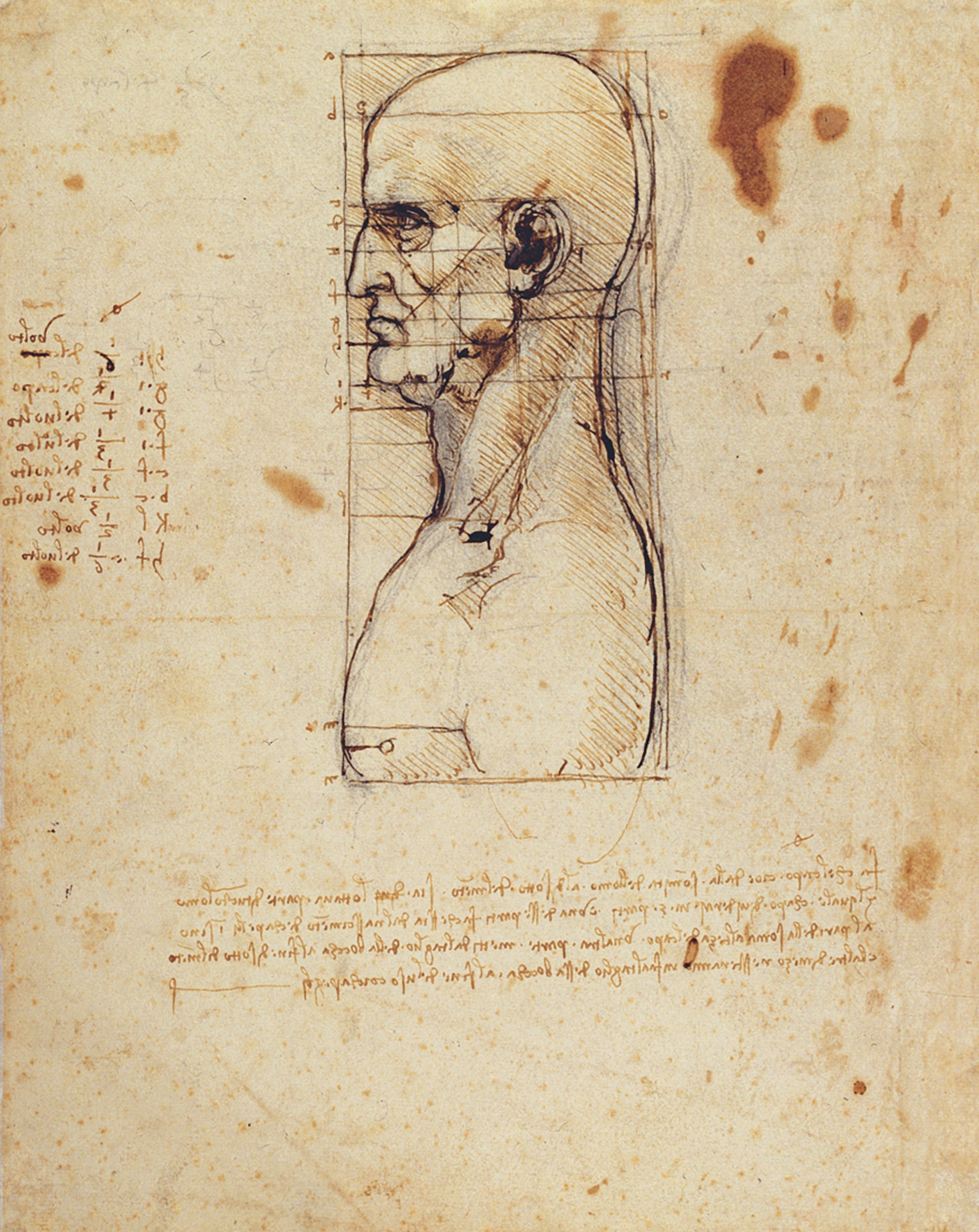

Mathematician

Obsessed with geometry, Leonardo made measurements in nature, seeking connections and patterns, and expressing them mathematically. He was especially fascinated by the proportions of the human body. Based on Roman architect Vitruvius’s work, Leonardo’s pen-and-ink “Vitruvius Man” (ca 1487), depicting a male figure in two superimposed positions with extended arms and legs within a circle and a square, explores the geometry of perfect proportions.

Leonardo sums up in backward-written text on the drawing how every part of the body is mathematically in proportion with the others: “Four fingers equal one palm; four palms equal one foot; … 24 palms equal one man.” This drawing also conveys Leonardo’s belief that the workings of the human body are analogous to the workings of the universe. “Man is the model of the world,” he wrote.

Leonardo also was familiar with the golden mean, a mathematical ratio that creates aesthetically pleasing compositions. Defined by a length-to-width ratio of 1:1.618… (a number designated by the Greek letter phi), it is associated with “divine proportion.” In his unfinished “St. Jerome,” for example, the figure of the ascetic is framed exactly by the superimposed golden rectangle. He also imbued the portraits of young women, including the “Mona Lisa,” with elements of the mathematics of aesthetics.

(See where Leonardo da Vinci still walks the streets.)

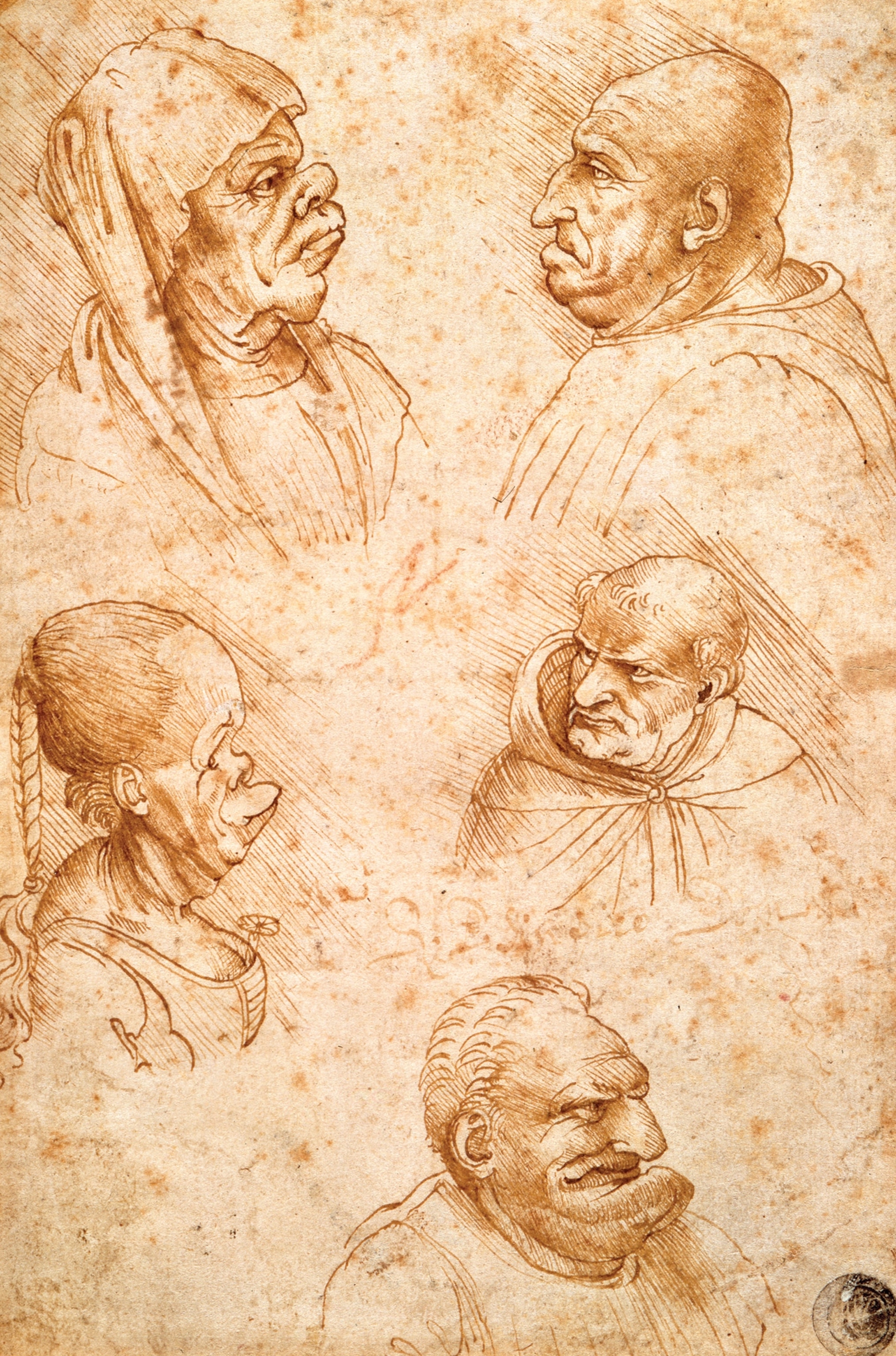

The grotesques

Architect

Drawings and plans for buildings fill Leonardo’s notebooks. He was fascinated by the problem of architectural aesthetics (as related to proportion) as well as the acoustics of church buildings.

He was determined to discover a structural combination that enabled the preacher’s voice to reach the most distant corner of the building. He invented the teatro da predicare—a lecture hall in the shape of an amphitheater.

He was officially appointed premier architect (and artist and mechanic) to the King Francis I of France in 1515. He designed military fortifications that took into account the increased use of artillery, creating sloped walls with a broadened base to prevent undermining by continuous bombardment.

In 1502 Ottoman ruler Sultan Bayezid II requested designs for a bridge, and Leonardo submitted a plan. The bridge had to span more than 900 feet across the Golden Horn at Istanbul, with an arch high enough for ships to pass beneath. Thinking Leonardo's bridge was not technically feasible, the Sultan turned down his submission, but modern architects proved the Sultan wrong in 2001, when they used da Vinci’s design to construct his bridge over a highway in Norway.

(What a 23-year excavation into the life of Leonardo da Vinci revealed.)

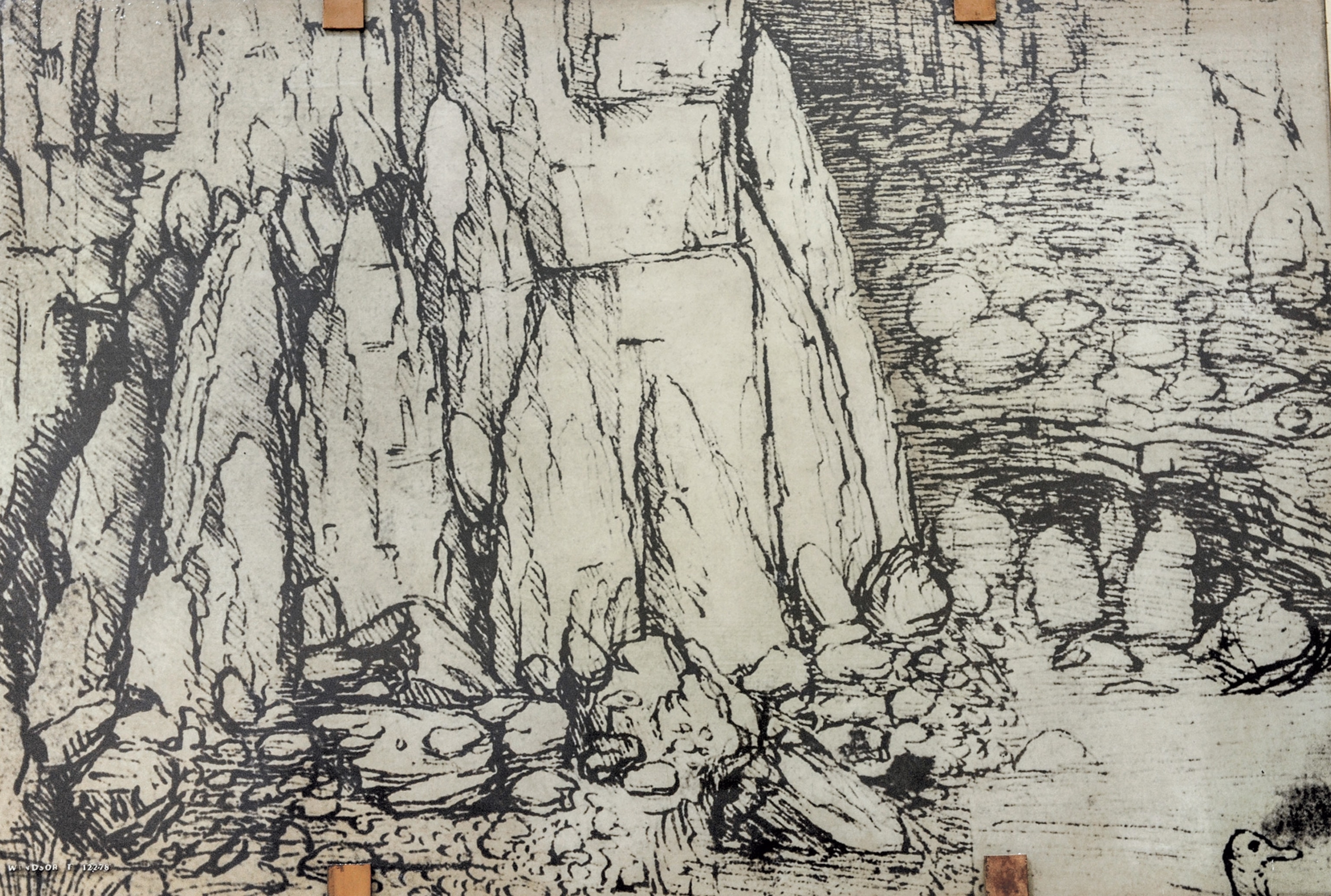

Naturalist

In the early 1490s, Leonardo twice headed north into the Italian Alps. There he jotted down observations and made sketches. Plants, animals, and, as always, birds were carefully described and recorded. These treks resulted in some remarkable drawings of thunderstorms that accurately depict the direction and force of the downdrafts known as wind shear.

He also examined fossils and land formations, and he made some of the first modern scientific speculations about geology and natural history. His drawings of cliffs show clearly the strata from different geological epochs. And most dramatically, he speculated about a much older origin for the Earth than the conventional view.

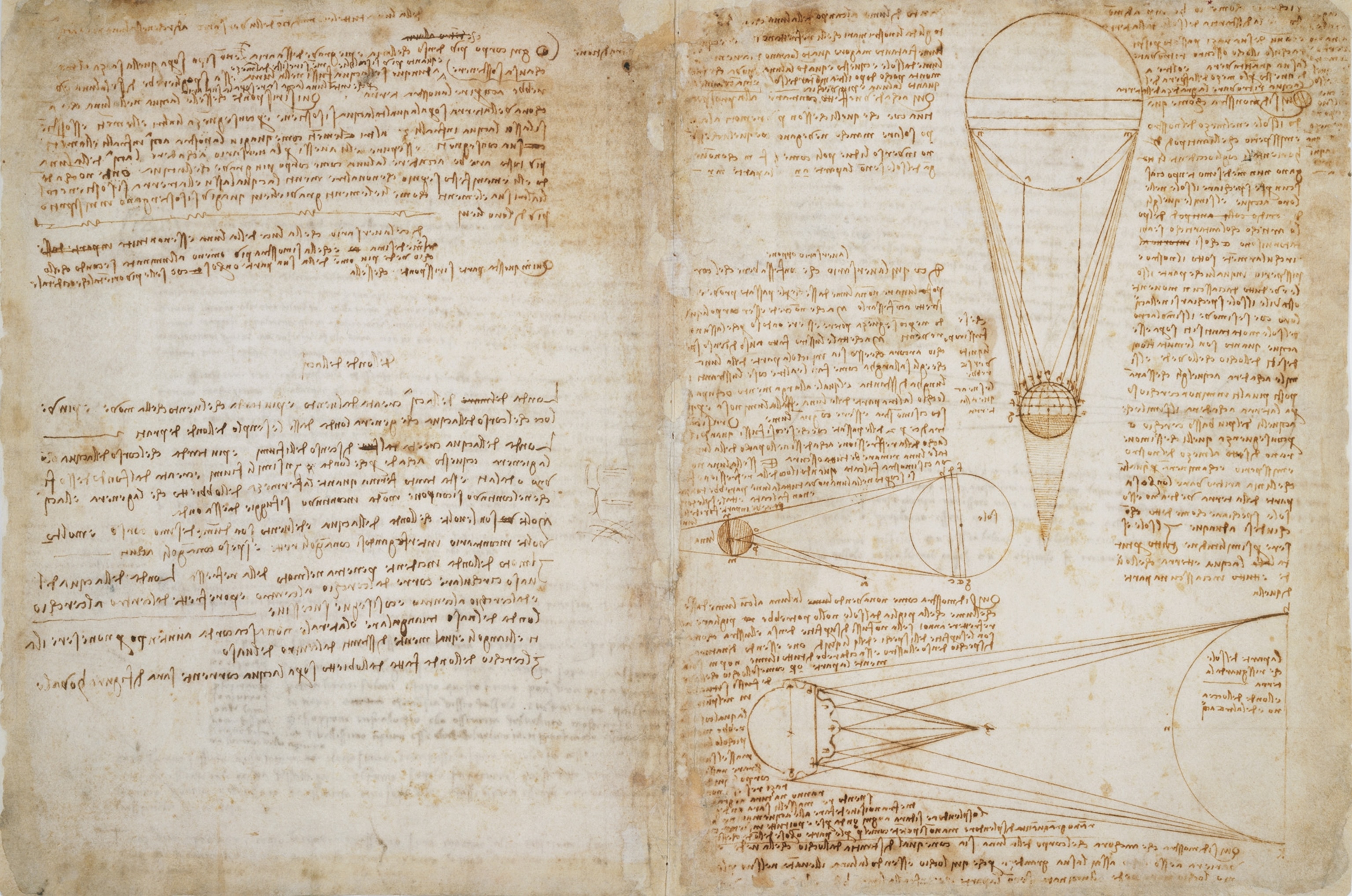

Leonardo’s fascination with nature took a deliberate and organized turn toward careful research and observation in the late 1400s, when he was living in Milan. He began a notebook devoted almost exclusively to a single line of scientific inquiry: optics, or the behavior of light. Careful and neat throughout, the drawings are meticulous, and they incorporate his knowledge of geometry. These are tantamount to modern lab books.

(Leonardo da Vinci transformed mapping from art to science.)

Inventor

Many say there are few modern inventions that weren’t inspired by Leonardo, including the parachute, the mirror-grinding machine, a pair of scissors, portable bridges, the mitre lock (still used on canals), and the spring drive (mostly used in toys). Some say he even designed the first robot.

He’s probably most recognized in the field of flight, long before the concept of a practical flying machine became reality. The genius produced over 35,000 words and 500 sketches on flying machines, along with birds in flight—birds, he wrote, are flying machines.

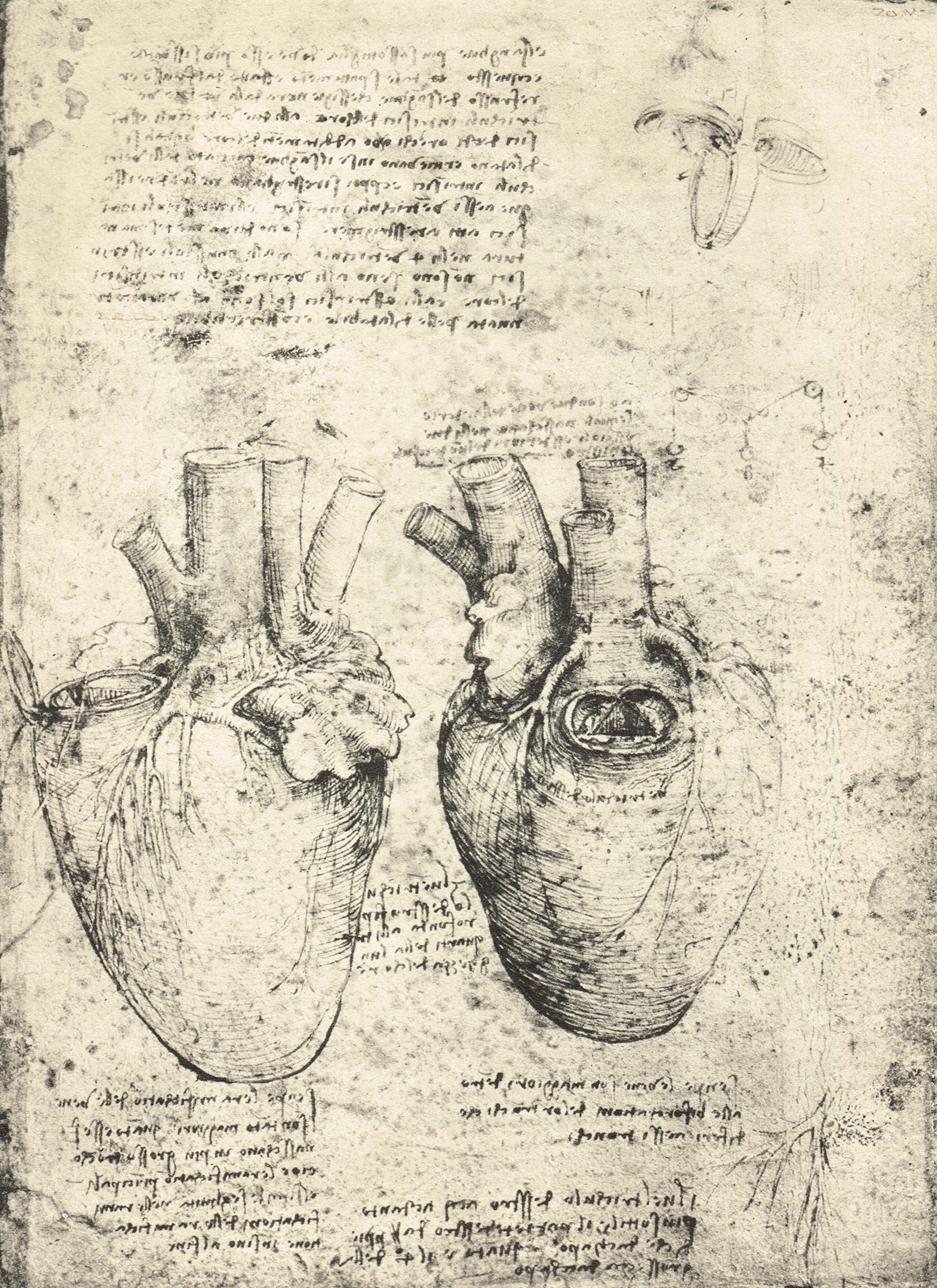

Anatomist

Leonardo recorded his studies of human anatomy in drawings and accompanying notes that revealed details never before described. Two human dissections proved particularly significant. The first on an old man described atherosclerosis—hardening resulting from plaque formation on a blood vessel’s interior walls—and arterial obstruction, a diagnosis of heart disease made hundreds of years before physicians recognized the symptoms. Around the same time, Leonardo performed an autopsy on a child and found the same vessels to be clear of obstruction and the vessel walls supple, a sign of the body before the ravages of age set in.

In Leonardo’s drawings, he also found a way to show features from as many as eight different angles, in cross section and in multiple cutaway views that peel back layers of muscle and tissue to reveal the levels of structure.

It was the human eye, though, that especially fascinated Leonardo, and he studied its structure, its connections to other organs, and its precise operation. In order to understand the eye, Leonardo devised a technique to carry out dissections by immersing the eye in egg white and hard-boiling it in order to make it firmer and easier to handle. Debunking the prevailing view of the eye as an organ that sends out invisible rays, he proposed that the eye is a receptive organ that “sees” by means of reflected light.

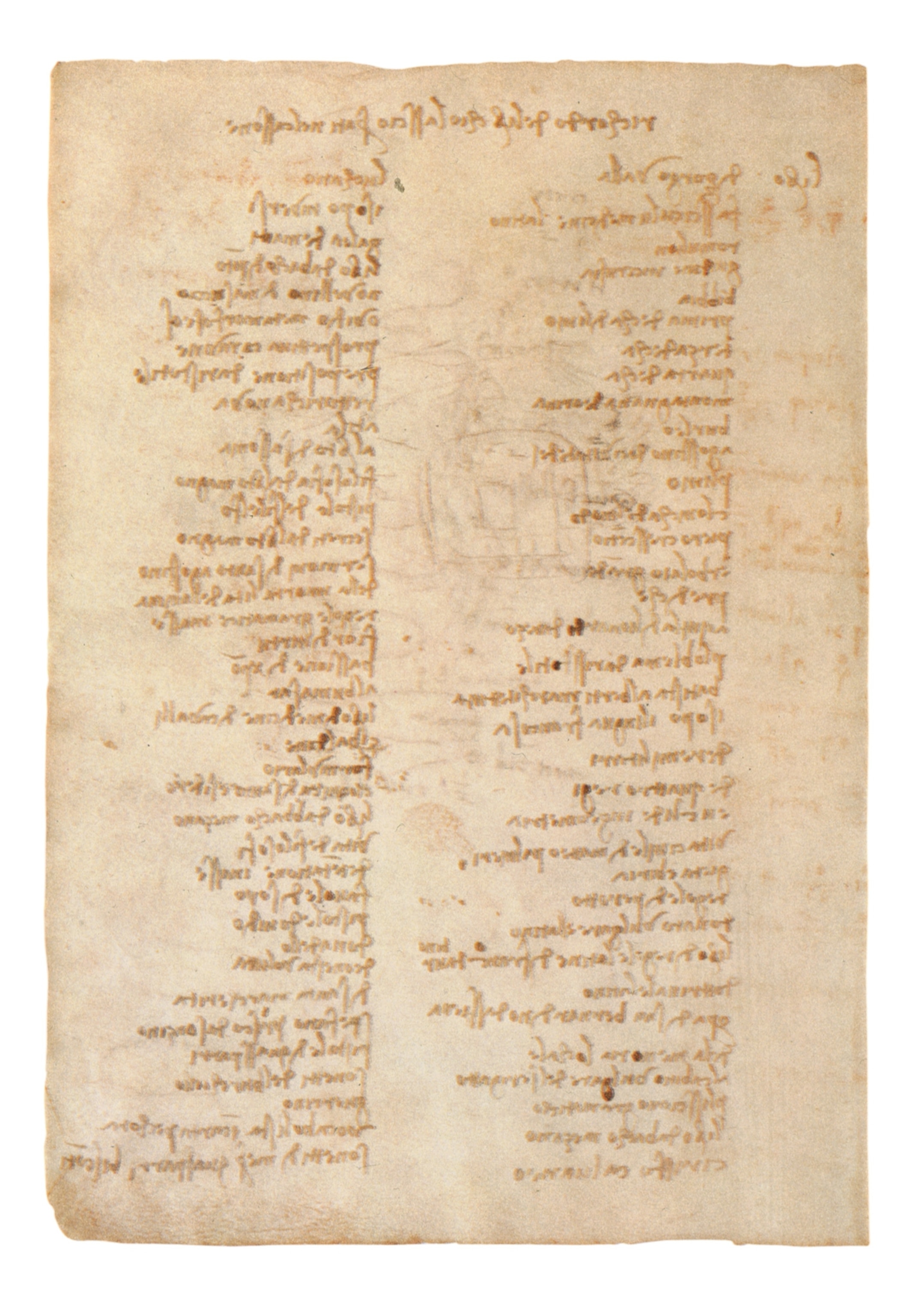

Leonardo's library

In the fall of 1504, Leonardo recorded another catalog of his books. The list had grown to 116 volumes—a very respectable number for his time—including some manuscripts written on vellum, which would have been expensive, testifying to his seriousness as a book collector. The new list included Alberti’s treatise on architecture, On the Art of Building, and the Summa de Arithmetica, a synthesis of the mathematical knowledge of the time written by mathematician Luca Pacioli, Leonardo’s close friend. By then, Leonardo had also expanded his collection of popular literature to include chivalric romances, satires, dramas, and even erotic and bawdy poems for leisurely consumption.

(The Renaissance 'Prince of Painters' made a big impact in his short life.)

To learn more, check out Leonardo da Vinci. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.