How Reyhaneh Maktoufi transforms science through story

Her research is helping build pathways between science and society.

Reyhaneh Maktoufi loves a good story. She uses it to make sense of the world.

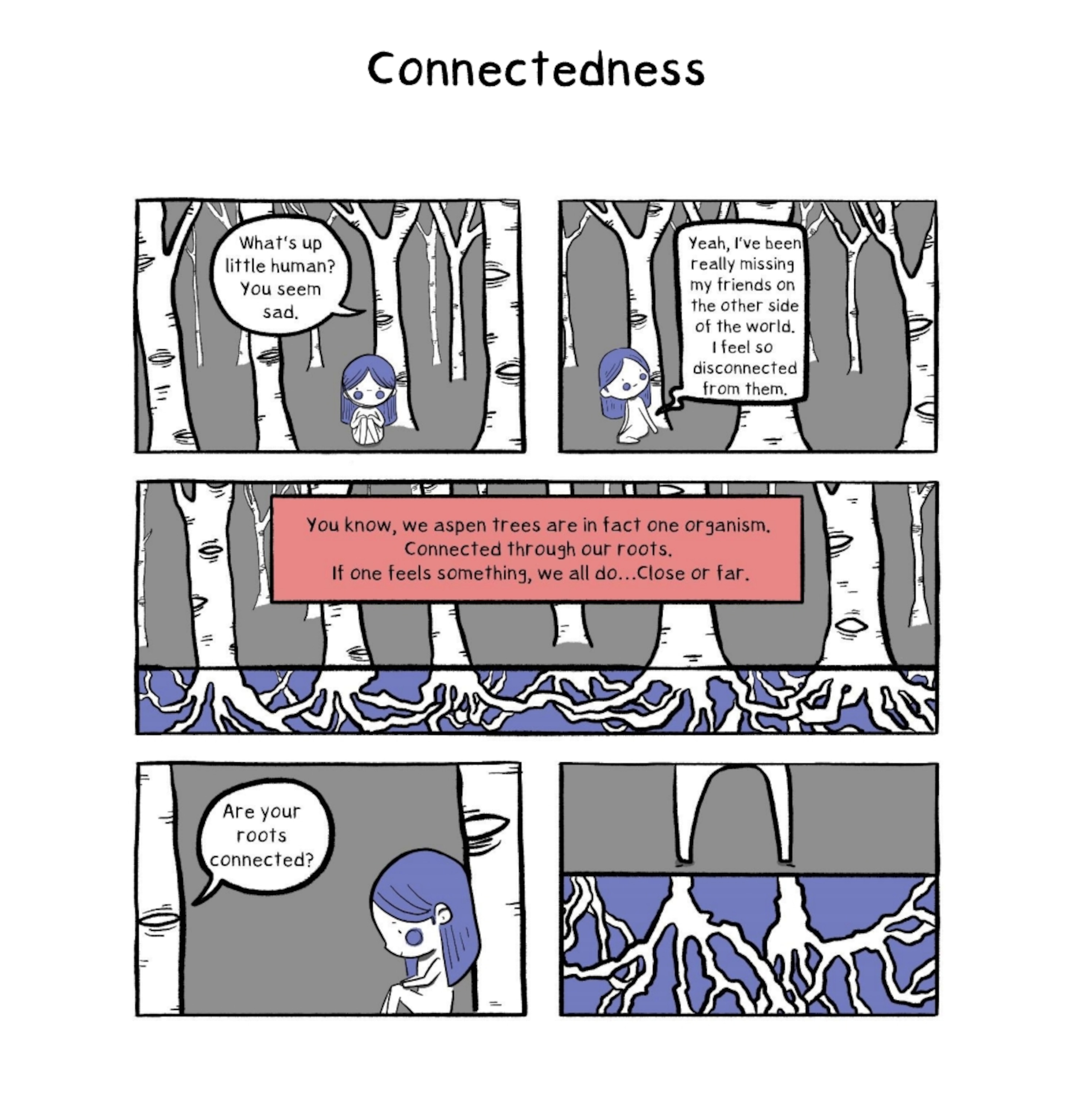

Her own storytelling style leans into humor. “As most people who are artists will tell you, I often scribbled in a notebook, doodling. Eventually, I saw that my bad drawings resonated with people,” she says. Sometimes the stories she tells are visual — comics and animations that break down complex concepts into digestible and entertaining narratives. Other times she’s a writer and orator.

“I am an alien,” she declared in Maktoufi fashion from the TEDx stage in 2017, then turning a technical glitch with her slides into an impromptu reflection on her life as an immigrant. In front of the live audience she improvised that the glitch was attributable to her extraterrestrial “powers,” and used the moment to explore how her Iranian-American identity shapes her work bridging scientific communities and the public.

Maktoufi is a science communication specialist, social science researcher and National Geographic Explorer who obtained her doctorate in media, technology and society with a focus on science.

Her start in bridging the gap between scientific and common language seven years ago at the Adler Planetarium Space Visualization Lab was, as she puts it, “the perfect environment for an alien,” surrounded by space images, moon rocks and in a place “not obsessed with national boundaries,” she explains. Here, she began a journey of investigating a deceptively simple question: What makes people curious about science?

She aims to make scientific knowledge more accessible by humanizing important and often complex work. “Numbers matter a lot, but we have to make them imaginable and tangible.”

Stories that connect

As a multimedia science communicator, Maktoufi has been the co-producer, host and illustrator of PBS NOVA’s “Sciencing Out” — a digital mini-series exploring how women in history communicated their scientific discoveries. She has worked as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute fellow to develop curricula and training for science communicators, and has been a producer for the podcast “The Story Collider”.

Science communication can bring people together and we need a mutual language for science and society to talk to each other

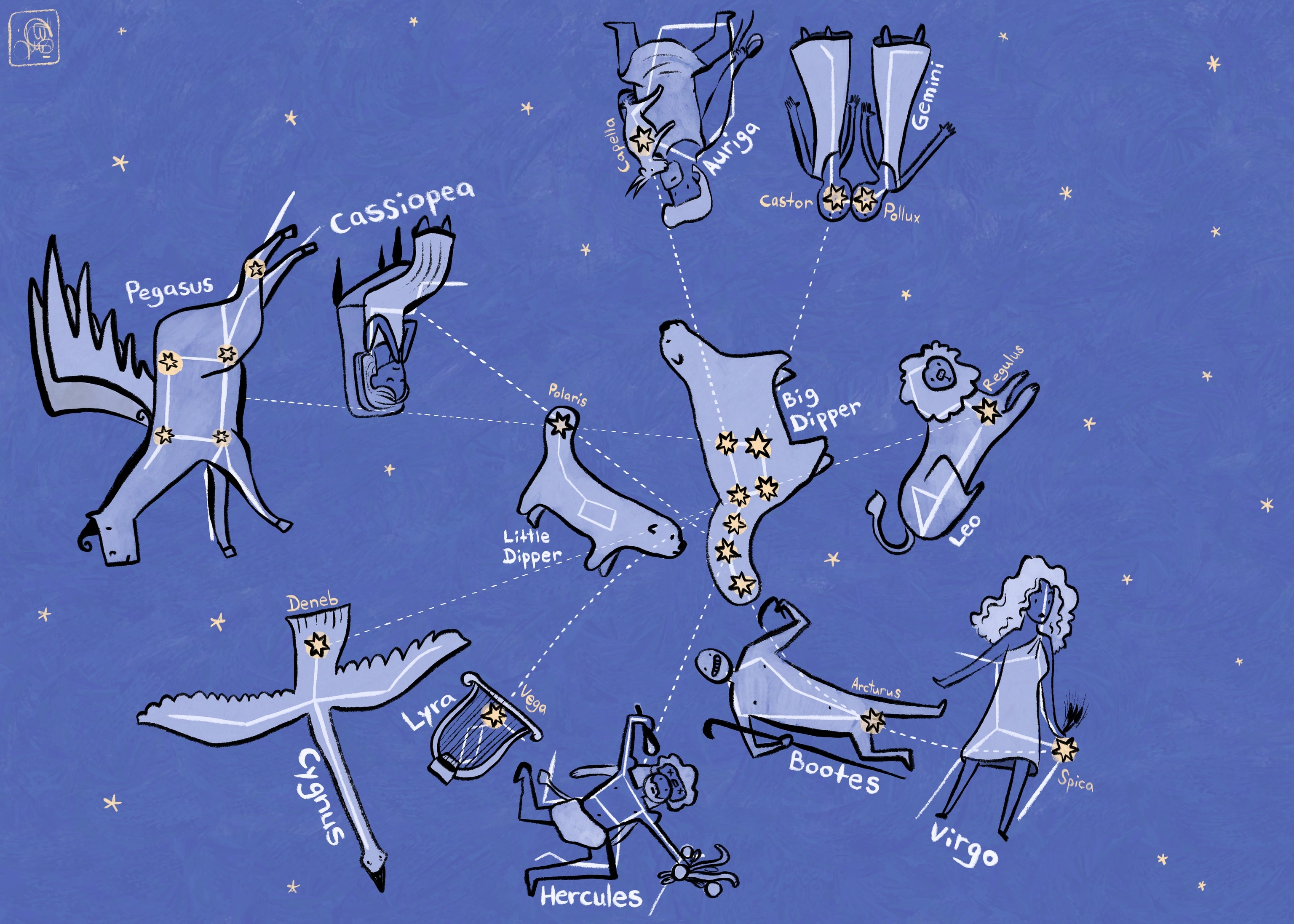

Growing up she inherited her brothers’ book interests. She mostly leaned into Greek mythology, which helped her understand the stars. Constellations disguised as celestial dramas of war and romance dramas helped her make sense of the immensity and mystery of the night sky.

“Ancient civilizations used stories to make sense of the universe. What are constellations but some stars scattered in the sky?” She muses. “But they gave them life. They turned them into lovers, siblings, parents … and sometimes, all of them all at once. Thank you Greek mythology,” she laughs.

Her curiosity and early appreciation for narratives became important when she began working as a physical therapist in Iran.

During long treatment sessions, patients naturally opened up to Maktoufi. “You just spend hours talking to people. And I noticed people kept coming back just to continue telling me their stories.” When she transitioned to working in pediatric hospitals, she experimented with reframing medical stories in a way that resonated with children. Empathy oozes out of her.

“Instead of discussions about lungs and secretions,” she explains, she spun tales about “caves filled with water” to help children understand what was going on in their bodies through digestible analogies, softened by humor.

“It really changes the feelings people have,” Maktoufi stresses. She integrated play and art therapy in her work with children facing terminal illnesses and through grief facilitation in hospice care. Her capacity for empathetic communication and information synthesis proved highly transferable across the sciences.

When she later became a visiting researcher at Chicago’s Adler Planetarium, Maktoufi bore witness to science communications’ community-building function in a different form. Facilitating communications workshops and keenly observing public-scientist interactions for hours, she noticed how scientists engaged with observers. “They might use a variety of ways to start the conversation or get people to ask questions. Things like surprising statements — that gets people asking questions. Silence, it’s awkward, it gets people asking questions. Or visual difficulty.” Here she observed something counterintuitive about effective science communication: Confusion can be an asset.

“If something is slightly confusing, it sparks intrigue,” Maktoufi says. “But it can’t be too confusing because then you lose people. Some degree of visual difficulty actually draws people in, and creates enough friction necessary for deeper engagement.” It makes people curious, it prompts more questions, and creates proximity. “And hopefully empathy.”

The science of science communication

Maktoufi’s opinion is that her communications findings may seem obvious at first. “People love stories, warmth and humor, that is clear. But when you look deeper, the story has to be good. And it has to be in the right context.”

Her approach to telling stories and understanding how people respond to them is experimental. She’s often testing the boundaries of how a message might land.

“Today I’m going to tell you a bad boyfriend story,” she once opened with during a presentation, drawing connections between the importance of a kind and competent support group through the breakup process to the qualities that make effective science communicators. On another occasion she engaged an audience with her contemplation of how farts are connected to the science of science communication. “I think they are surprising, and they get people curious and engaged and asking questions,” she disclosed.

%20.jpg)

She once asked grief workshop participants to channel their emotions into an elaborate origami. Then, she tore them in front of the participants and disposed of them in the trash. She asked them to describe their grief process. “People bargained with me, or hid them, or took pictures.” One person took Maktoufi’s origami and angrily destroyed it in front of her.

“I was like, ‘Oh, this impacted people. They are having emotions.’” The following workshop she hosted she took the paper creations away, but returned them at the end, intact. “Push boundaries,” she insists. In science communication and any field of exploration “you will mess up and then you will make it better,” she says.

In her trust-building workshops, Maktoufi fosters vulnerability by having participants share something that has made them nervous before the session, and they reflect on how it felt to be heard at the conclusion. Maktoufi participates too. “Usually we discuss how vulnerability helps us feel closer to each other, feel more positive about each other, and eventually it helps us in the trust process.”

Or, when she teaches about audience strategy, she challenges participants to consider how to convince “exaggerated audiences,” — like cats, zombies, time travelers from the past, or even aliens looking for an inhabited planet — to “plant more fish-faced flowers.” The bloom is, “a made up flower,” Maktoufi clarifies. The idea, she explains, is that “participants have fun, but also think carefully about their audience and how the strategy they come up with has to really fit those exaggerated audiences.”

%20.jpg)

Much of what Maktoufi is doing is helping scientists first understand who they’re talking to, then develop the best approach to doing it. “It is the science of science communication,” says Maktoufi, and it works backwards.

Practically, this looks like conducting surveys to identify audiences’ values, then considering how to deliver the message.

“There are many ways to say the same thing. Sometimes what you’re trying to say is true and valid but you’re not speaking the audience's language, so you have to pivot." The same conservation message, for instance, might emphasize rewilding when directed at hunting communities, while highlighting “environmental justice concerns” for activist audiences.

In 2024 Maktoufi was named one of 15 recipients of the Wayfinder Award presented by Kia, for their local and global boundary-pushing contributions. Since, she’s helped launch Story Craft with Science Communication Lab, an initiative that hosts events connecting science communication and social science researchers with each other and National Geographic Explorers.

In addition, Maktoufi and fellow Explorer and documentary filmmaker Sonya Lee are planning a collaboration — a joint investigation of science communication as applied to ocean and food systems.

“It sounds cheesy,” Maktoufi calculates, but ultimately she wants her work to build empathy.

“As human beings with all of our differences we share a greater mutual ground. The same sun that shines on us every day and the same night sky that puts us to sleep, the laws of physics are our mutual ground,” she explains to an audience from the stage.

Maktoufi recognizes the human impulse to make meaning from mystery. Her work demonstrates that effective science communication doesn’t eliminate complexity, but it transforms it into curiosity.

“Science communication can bring people together and we need a mutual language for science and society to talk to each other,” she concludes. “We need stories to make sense of the uncertainty of the universe.”

ABOUT THE WRITER

For the National Geographic Society: Natalie Hutchison is a Digital Content Producer for the Society. She believes authentic storytelling wields power to connect people over the shared human experience. In her free time she turns to her paintbrush to create visual snapshots she hopes will inspire hope and empathy.