A new beetle species found in Triassic feces, and more breakthroughs

Surprising discoveries in fossilized droppings, shrew brains, and a coffee-coated rainforest

Scat scan discovery

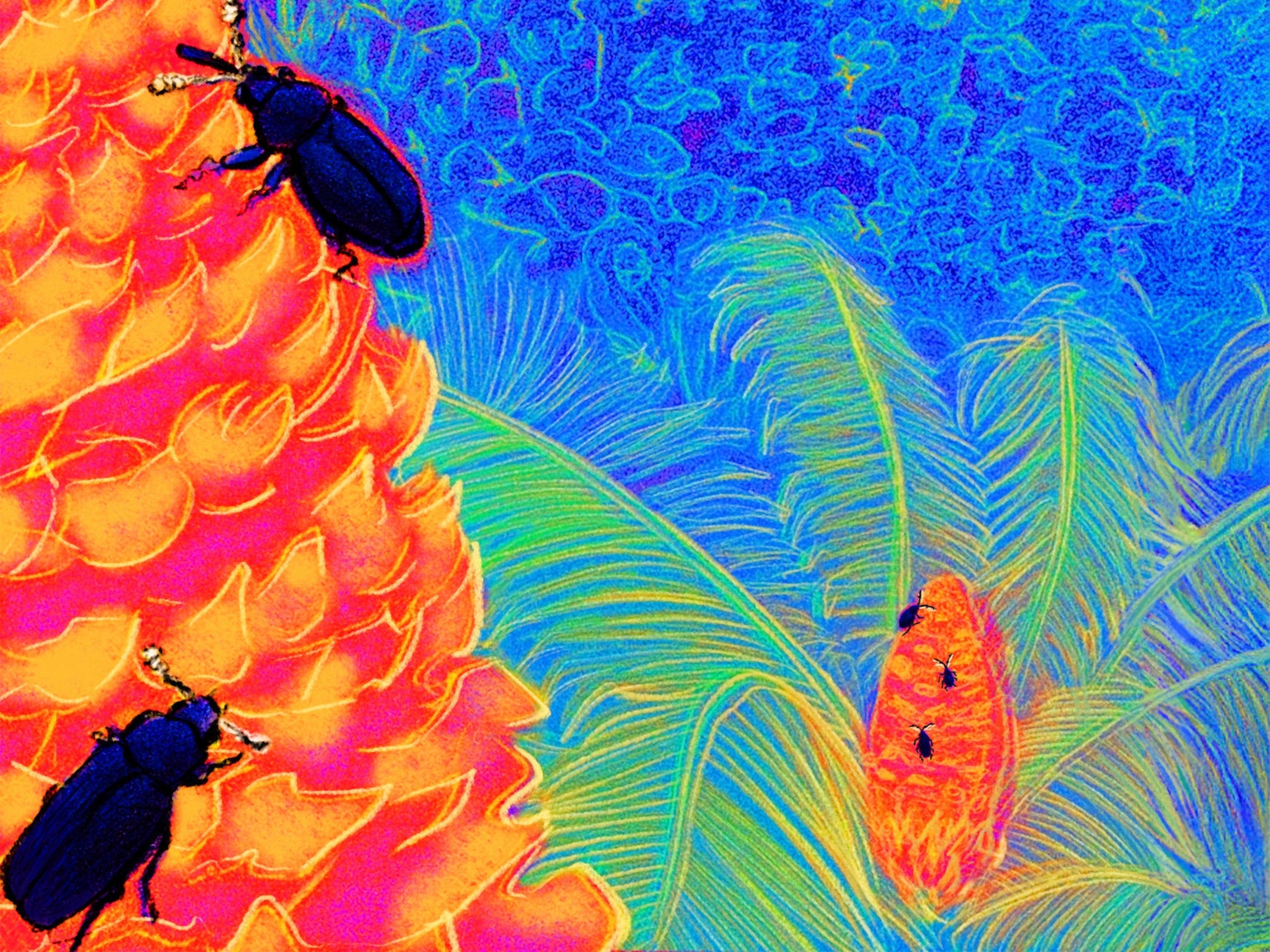

Some very old objects come in exquisite containers—gilded sarcophagi, carved chests—and others, in less appealing packages. The newfound beetle Triamyxa coprolithica is among the latter. A team of scientists reported discovering the species in a coprolite, aka fossilized feces. The team used synchrotron microtomography, a powerful x-ray technique, to scan an ancient dropping that the scientists had unearthed in Poland. Inside the 230-million-year-old scat, nickel size in diameter, were partial and whole specimens of the tiny beetle (above). Study lead author Martin Qvarnström says that to see 3D scans of the bugs, “it’s like they’re becoming alive in front of you.” With even some of the delicate legs and antennae intact, the remains were preserved well enough to identify the beetles as a previously unknown, now extinct species—the first time an insect species has been described from a coprolite. The researchers theorized that the dung came from Silesaurus opolensis—a dinosaur relative up to eight feet long—and hope their discovery will encourage more stool sampling by paleontologists. —Hicks Wogan

The saving of the shrew

Unlike seasonal hibernators, the Etruscan shrew—one of Earth’s smallest mammals—must eat heartily year-round to stay alive. But the insectivore may have a different way to conserve energy in winter: It shrinks a section of its brain by more than 25 percent. The lost cells regrow by summertime. —HW

New forests benefit from coffee’s jolt

Just like us, forests move a bit faster when there’s coffee on hand. An experiment in a Costa Rican rainforest covered deforested land with pulp that’s a by-product of the coffeemaking process, to see how it affected forest regrowth. After two years, the pulp-covered forest plots were doing much better than untreated ones—giving coffee producers a new, sustainable alternative to dumping their waste. —Sarah Gibbens

This story appears in the February 2022 issue of National Geographic magazine.