Black America’s Story, Told Like Never Before

A new museum in Washington shows the personal side of African Americans' suffering, perseverance, and triumphs.

If not for a chance encounter with a soldier in fatigues at a Mercedes-Benz dealership, just outside Sacramento, California, Gina McVey might never have known that her grandfather had an esteemed role in American history.

While making small talk in the waiting room, McVey mentioned that her grandfather had served in the First World War. The questions that followed were almost reflexive: “What did he do? Where did he serve?” McVey had few answers.

Lawrence Leslie McVey, Sr., was a faintly drawn branch on the family tree. He’d lived on the other side of the country, in New York City, and died when she was just 10. She’d met him only twice. McVey, a risk consultant for Wells Fargo, did know one detail that was family lore: Her paternal grandfather had received a fancy medal from the French government, but she couldn’t recall the name of the honor.

“The look on his face when I mentioned the medal was priceless. He asked if my grandfather was a black man,” McVey says. It was a reasonable assumption since she is an African-American woman with chestnut skin and dark eyes.

“That’s when he said the name of it,” she continues. Croix de Guerre. “I may be saying it all wrong, but he wanted to know if my grandfather had received that specific medal.”

McVey recalls what he said next. “Do you know what you have? You have history.”

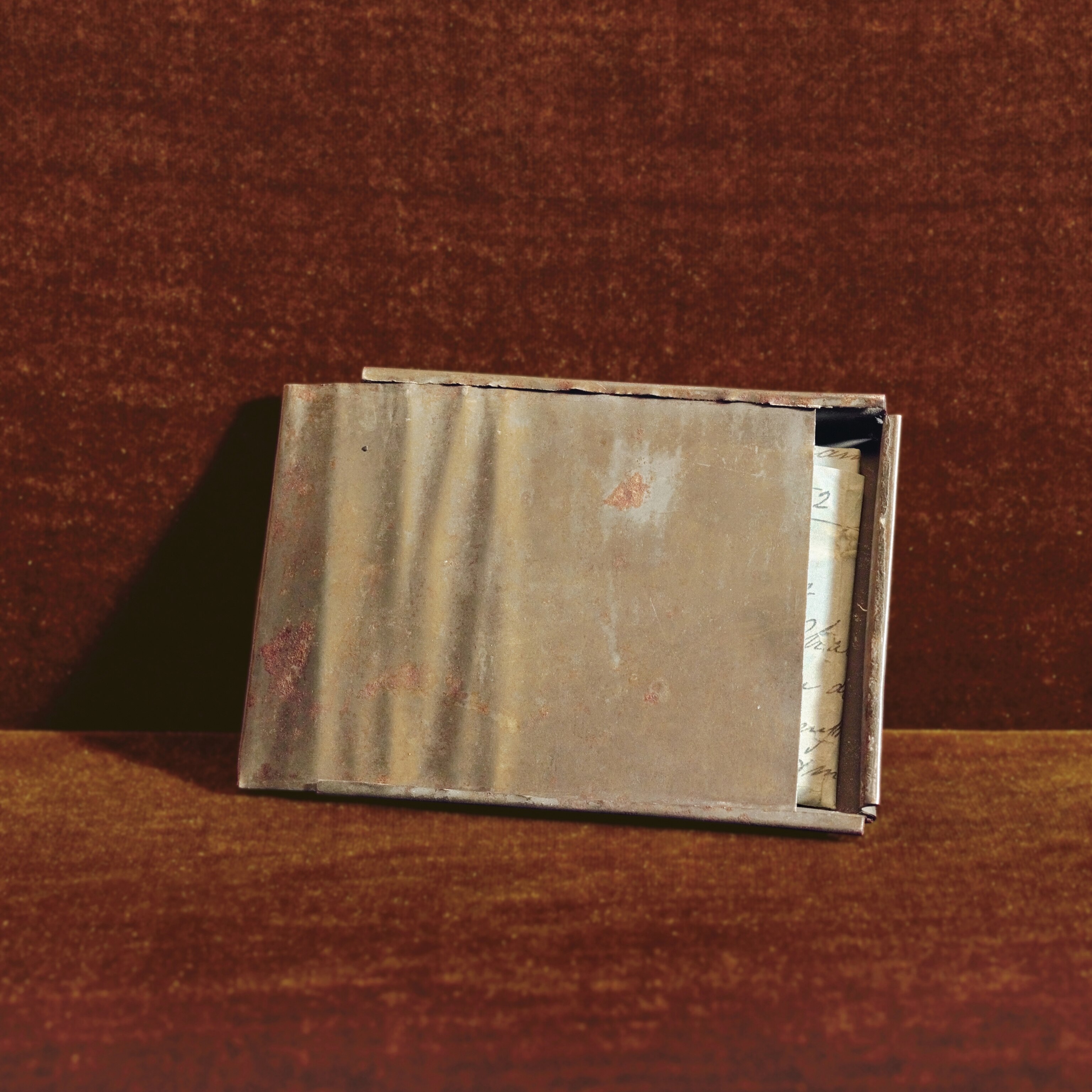

Those words, coming from a man in uniform, felt like a command. Within an hour she was researching World War I’s black soldiers on her computer. Within four weeks she was at her mother’s Los Angeles home, combing through a metal box that had been stuffed in a bedroom chest since 1968—the year her grandfather died. And within four months Gina McVey was in Washington, D.C., delivering the contents to curators at the new National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“They were floored by what they saw,” McVey says. What they saw was a trove of military medals, commendations, photographs, and newspaper clips that detailed her grandfather’s service in the 369th Infantry—an all-black regiment so fierce that it came to be known as the Harlem Hellfighters. Barred from serving in combat alongside white soldiers, the black soldiers were assigned roles as cooks and stevedores, but eventually redeployed to replenish depleted French forces. Their heroism, now little remembered, was once known around the world.

“I never learned any of this in school,” McVey says. “It’s been sitting there waiting for someone to say, ‘This is important. We need to share it.’ ”

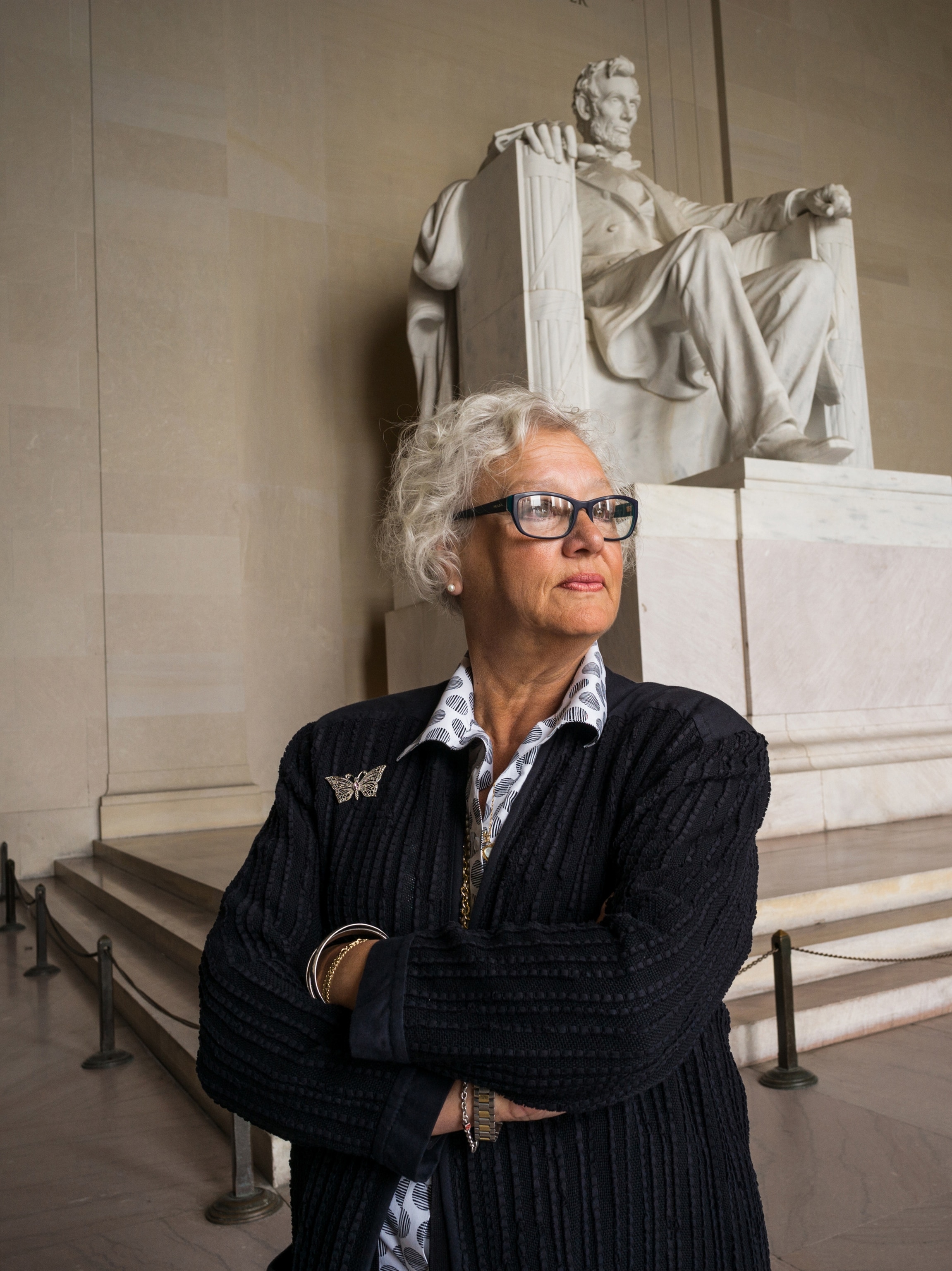

The Smithsonian Institution's museums are where the world comes to learn what it means to be American. This September the newest museum joins that pantheon with a distinct mission: to reframe American history through an African-American lens. It is, says Lonnie Bunch, the founding director, “a clarion call to remember.”

Whether it’s the hymnal carried by abolitionist Harriet Tubman, the Cadillac driven by rock-and-roll legend Chuck Berry, the inkwell used by writer James Baldwin, the dress sewn by civil rights icon Rosa Parks, the Jim Crow–era segregated railroad car, or the guard tower from Louisiana’s notorious prison in Angola, each object in the museum will highlight a chapter in a historical narrative that includes bondage, oppression, liberty, and perseverance.

Visitors—expected to top five million a year—will also be able to see Lawrence Leslie McVey’s Croix de Guerre and learn about the valor of the 369th, as well as the prejudice that was U.S. Army policy. That ugly truth was clearly spelled out in a secret 1918 military memo explaining that “although a citizen of the United States, the black man is regarded by the white American as an inferior being.” The memo advised French officers to avoid eating or shaking hands with black soldiers or even praising them, to keep “from ‘spoiling’ the Negroes.”

In some ways the new museum is a cultural measuring stick. A country that refused to offer respect or even basic humanity to African Americans is honoring black history in an extraordinary way. Everything about the new museum is bold—the mission, the collection, the $540 million building inspired by ancient African art and principally designed by David Adjaye, a British architect born in Tanzania to Ghanaian parents.

To say the museum stands out is an understatement. It sits on prime real estate, steps from the White House and across the street from the rolling green that surrounds the Washington Monument. The building is faced with a deep brown metal latticework similar to the intricate designs that African-American metalsmiths crafted for the ornate gates and balconies of New Orleans. Bunch explains: “I wanted a building that spoke of resiliency, uplift, spirituality, but I wanted a building that had a dark presence.”

It is also angular and aesthetically aggressive, an homage to the wonderfully flamboyant style African Americans often assert to convey confidence and cultural urgency. Church hats. Zoot suits. Cornrows. Bling. Situated at the gateway to the rows of stately Smithsonian buildings on either side of the National Mall, it’s as if Beyoncé, in one of her bejeweled costumes, strutted into a Wall Street meeting filled with gray suits.

I pass the building often, and I feel a little emotional jolt every time. The first time I took a tour, I saw something that put words to what I felt so viscerally. Everything about the building screams, “I, too, am America.”

Those words, in huge bronze letters on the wall in one of the museum’s exhibit spaces, are the final line from the poem Langston Hughes titled simply, “I, Too.” Written while Hughes was in Europe and denied passage on a ship home because of his race, the poem speaks of “the darker brother” forced to eat in the kitchen, who nonetheless eats well and grows strong with the certainty that one day he will be “at the table when company comes.”

“Besides,” Hughes writes, “They’ll see how beautiful I am. And be ashamed. ”

At their best, museums help us understand and interpret our complex world by illuminating history and influencing attitudes. That becomes a challenge when we must examine our darkest episodes. Any society scarred by war, genocide, famine, displacement, or slavery must decide what to remember and how to remember. Individual memory is one thing, but collective memory stretches across generations and helps define a nation’s character.

Museums play a critical role in constructing collective memory—in this case turning the country’s gaze toward a history it might otherwise choose to forget. Slavery, sanctioned by law in America for more than two centuries, has shaped almost every aspect of American life, and yet it doesn’t hold a place of primacy in America’s historical canon. From slavery to segregation to soaring victories, this new museum takes an unflinching look at the travails and triumphs of African Americans.

Discoveries like Gina McVey’s are a particular thrill to the museum’s curators. They began their work a decade ago believing that many of the artifacts, documents, and treasures that would reveal the story of African Americans were secreted in basements, attics, garages, and storage trunks. Items with high monetary value might be in the hands of collectors, but the curators had a hunch that many with great significance were still undiscovered, because many museums have overlooked black history.

But there was another realization that led curators to believe so much black history was still buried. Black families in many cases have been unwilling to excavate their own past because it is soaked through with so much pain. African Americans are still joined at family tables by those old enough to have lived through a period of second-class citizenship, when laws dictated where they could eat, live, work, or educate their children. And yet many who survived the dehumanizing and degrading system of segregation decided that the best way to move forward was to avoid dwelling on the past. Their focus was fixed forward. Onward. Upward.

In my own childhood, my father and his five brothers would talk all the time about “traveling light.” When someone asked, “How’re you doing?” the answer was, “Traveling light.” I was well into adulthood before I realized they weren’t talking about the kind of baggage that has handles. They were from Birmingham, Alabama, and they all had moved north, looking for a better life and a place where their children might take flight.

To move skyward, certain things were simply locked away. Besides the Croix de Guerre, the metal box of military keepsakes that McVey found included her grandfather’s Purple Heart, a sharpshooter medal, a thank-you letter from the French government, and photos of her grandfather in the uniform of the U.S. Army. “On one of the pictures my grandmother wrote at the top, ‘hero.’ That just touched my heart,” she says. “I just knew he won a medal. I just sat there and cried.”

How does a family forget all that?

The Harlem Hellfighters returned to a hero’s welcome in New York City, showered with cigarettes, chocolate, and coins that jingled off their steel helmets. But when the parade was over, the soldiers were back in a country that did not see them as equals. In 1919, the year they returned, hundreds of African Americans were killed by white mobs across the country as racial tensions erupted in what was called the Red Summer.

“The more I learned about not just my grandfather’s service but the world he walked back into, the more I understood why this whole history just got lost,” McVey says. “It was hard. Too hard.”

To Rex Ellis, the museum’s associate director for curatorial affairs, the charge is to tell the whole story, “not a part of the story, not the portion that some people are most comfortable with.” This mission is not without controversy, as Ellis learned when he uncovered the history hidden in plain view in his hometown.

Ellis grew up in Williamsburg, a former capital of Virginia. Colonial Williamsburg, the sprawling living history museum where actors wear period costume, is the center of modern-day civic life for the city’s residents. Yet when Ellis was a boy, he was never allowed to visit. One day he asked his father why, and the elder Ellis shot back: “Because that’s something that points to slavery, and that’s something we don’t need to know about.”

More than a decade later, Ellis was teaching theater history at Hampton University in Virginia when a representative from Colonial Williamsburg visited the campus looking for actors to play the parts of slaves. Telling the story, Ellis rolls his eyes. “You don’t go to a predominantly black college and make a statement like that unless your cause is just or you’re ‘touched,’ as my grandmother used to say,” he explains. “He said he wanted to begin talking about the other half of the population in Williamsburg during the 18th century, and he wanted us to help him do that.”

Black people had always worked in costume at Williamsburg, as blacksmiths, scullery maids, bookbinders, and carpenters, but they were silent. Ellis introduced a new paradigm: Slave interpreters would describe in scholarly detail how they worked, lived, found fleeting dignity in private rituals, and endured a life of bondage and brutality. Ellis is a trained actor with a voice like cognac and a way of using his whole body to punctuate words, much like a conductor in front of a symphony. So he was able to poignantly portray a slave who would face severe punishment for attempting to learn the alphabet—and then break character to stand erect and deliver a rousing history lesson. It was a hit with tourists, but it made Ellis a pariah in Williamsburg’s black community.

“It was very, very, very controversial,” says Ellis. “Those first two or three years were very, very difficult years. I mean, when you have black employees who come to see what you’re doing, and they turn around and walk away, and you have people walking up to you and, when they see you in costume and they see you talking, they start whistling ‘Dixie,’ it can get hurtful.”

His father never came to see his work as a slave interpreter. “In the end I think he understood that I was not just giving us back our history, I was giving people back the dignity they deserve in their history. The dignity,” he says, repeating the word for emphasis. His father did not live to see the museum, but Ellis keeps him in mind when thinking about its goals. “You have to convince some people of the importance of this work. It helps me understand that we have to work hard and work carefully to bring people along.”

The museum's culturally diverse team of curators has spent the past decade making the case that examining the black experience is key to understanding America. It’s a high-stakes approach, particularly within the Smithsonian’s conflict-averse culture.

In 1995 the National Museum of American History installed an exhibit featuring a section of a Woolworth’s lunch counter from Greensboro, North Carolina, where four black students in 1960 protested whites-only service by launching a sit-in that spread nationwide. Some vocal North Carolinians feared that it would create a black eye for Greensboro on the National Mall. Woolworth officials worried it could hurt their brand. Some African Americans objected that it was Disneyesque, emphasizing the nobility of the students rather than the racism they were fighting. All that conflict about a single exhibit. Now imagine a collection of nearly 40,000 objects.

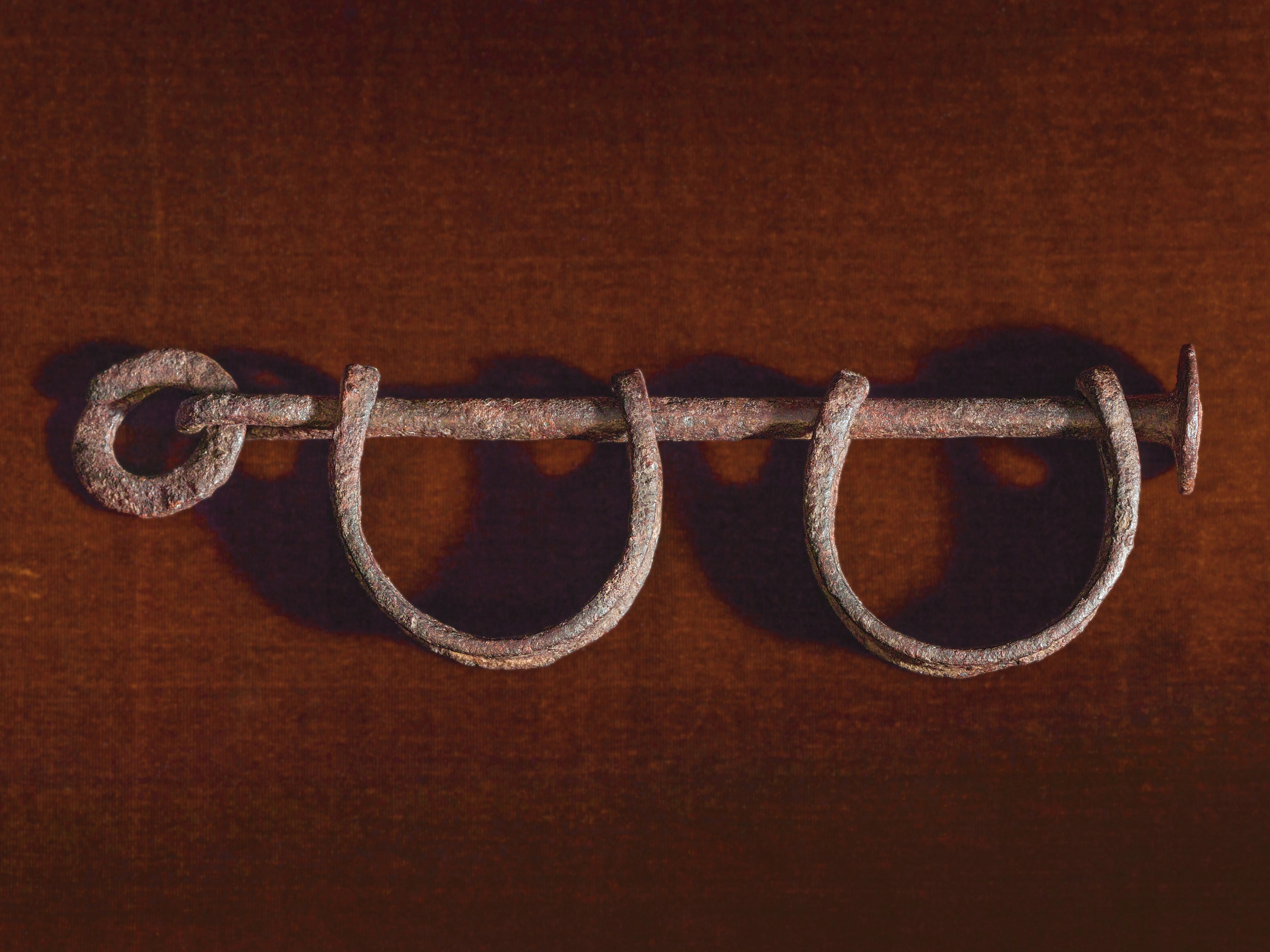

The exhibits have a strong point of view but are based on rigorous scholarship. And even though the museum speaks primarily with a black voice, the approach is meant to draw in visitors of all backgrounds. The experience begins underground—a bit of choreography that evokes the National Association of Colored Women’s motto, “Lifting as We Climb.” Visitors learn about a new nation struggling to establish the rule of law and wrestling with the “paradox of liberty.” Nowhere does it explicitly say slavery was an abomination or segregation was evil, but through carefully designed exhibitions, visitors are encouraged to examine political, economic, or moral issues from a very personal vantage. The idea is that learning about a slave shackle might prompt a visitor to contemplate what it would be like to wear the iron cuffs or clamp them on someone else’s ankles.

“You will see yourself in this exhibit, regardless of your race,” says Mary Elliott, who helped create the Slavery and Freedom exhibition, which presents the contradiction personified by the nation’s third president: the framer of the Declaration of Independence and a slaveholder. “We humanize this story, so if you are a man, if you are a woman, if you are a child, you look at Thomas Jefferson and say: What would I do? How would I have justified it?’ ”

Some who donated artifacts say that was part of the attraction. For the musician Chuck D, emcee of the politically confrontational rap group Public Enemy, the museum is in keeping with his group’s 1989 number one single, “Fight the Power,” in which he laments that “most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps.”

“First, the fact that they wanted to include hip-hop and rap in the history of African Americans in America was impressive,” says Chuck D, whose real name is Carlton Douglas Ridenhour. “Add to that they wanted to confront America, to ask America to confront itself, and look at all of its people and all of its history. That’s power.”

Chuck D and his bandmates gave the museum a boom box used in their 2010 tour that’s so large it could serve as a coffee table.

For Olympic medalist Carl Lewis, the appeal of the museum is that it offers a kind of immortality for his accomplishments and his story. Lewis idolizes the track star Jesse Owens, who won four gold medals at the 1936 Olympics, but marvels at how many young people don’t know Owens’s story. Lewis said part of his motivation was to make sure people remember not just his medals but also the story behind them. Nine of his 10 medals are at the Smithsonian—all but the one he placed in his father’s casket. “I’ll just be honest,” Lewis says. “You know it’s just weird that in maybe a hundred years it’s still going to be there. I’m going to be part of American history. I mean, that’s my selfish part. It’s really that this little goofy kid from Willingboro, New Jersey, that people laughed at, is in the Smithsonian.”

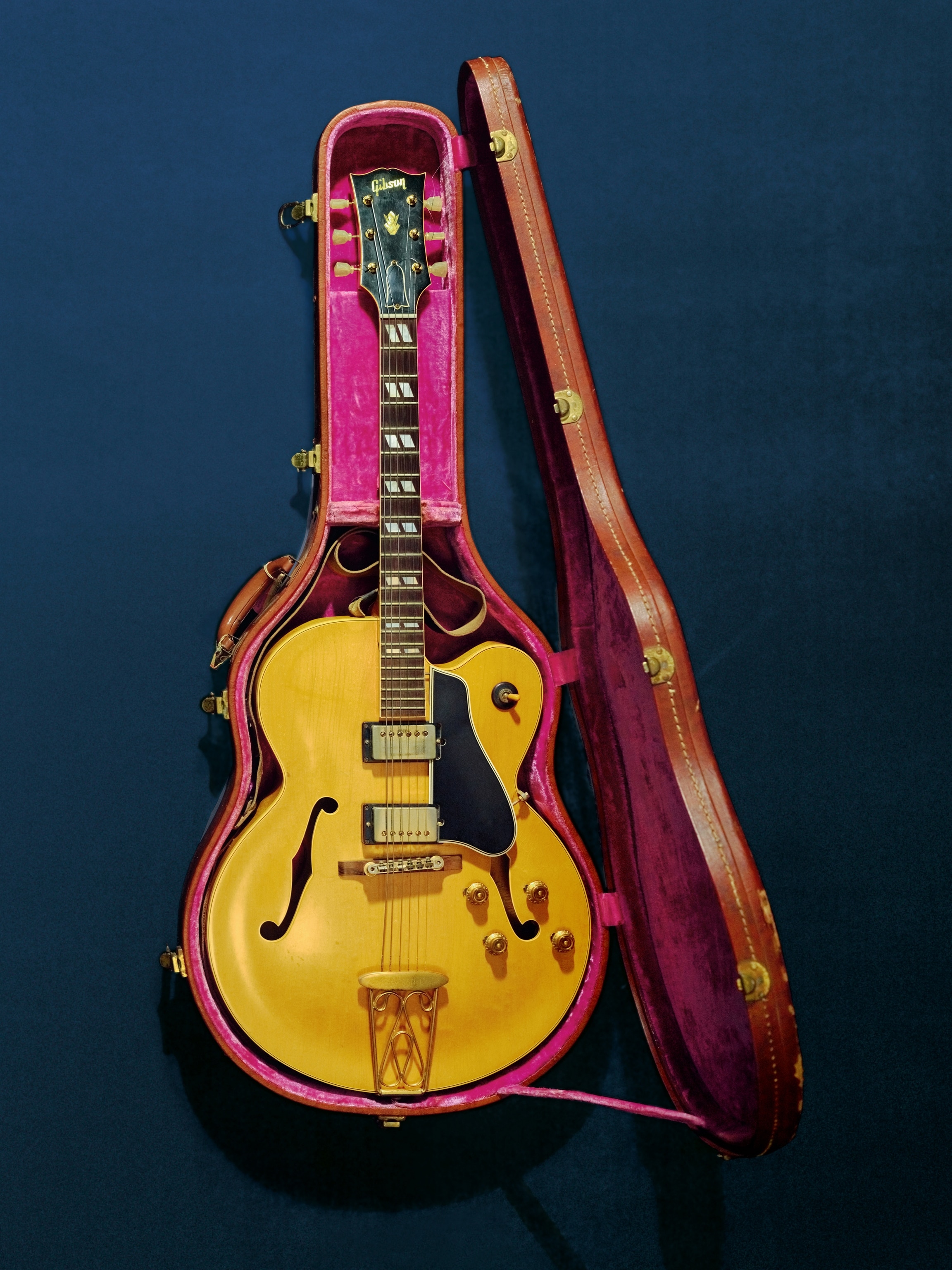

Even objects that represent triumph have the contextual backdrop of overcoming daunting barriers. Take, for example, Chuck Berry’s 1973 convertible Cadillac Eldorado. It is a stunner of a car. Lipstick red with whitewall wheels and a hood ornament that gleams like a chandelier. Even as it screams of self-determination, there’s a backstory of denigration. During filming for the documentary Chuck Berry: Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll, Berry, who was about to turn 60, drove that car across the stage of the Fox Theatre in St. Louis—the same theater that had refused him entry when he was a boy. In the museum Berry will be remembered as a pioneering guitarist whose music appealed to black and white teenagers, setting the sonic template for future legends, including Keith Richards, Pete Townshend, and Dave Grohl.

From the outset the goal was to create a new collection rather than poach what little other museums had. The museum’s temporary offices were filled with whiteboards and yellow sheets listing people, milestones, events, and themes: abolition, the Civil War, dance, sports, black newspapers, transportation, incarceration, protest movements, business districts, agriculture, maritime work, hair, comedy, family life.

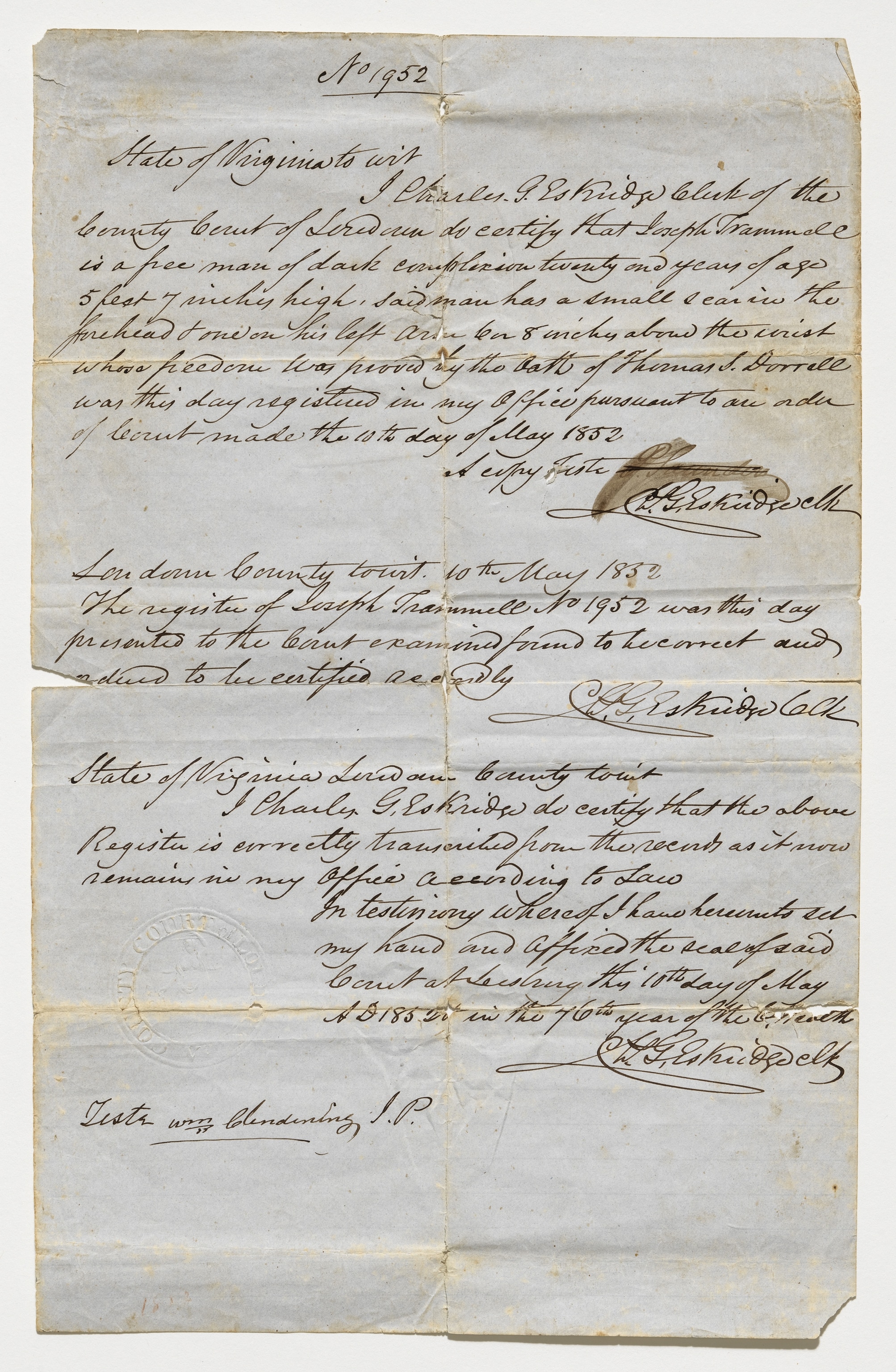

The curators wanted artifacts that represented historic milestones but would reveal those stories in a personal way. Ordinary items to tell extraordinary stories. They found a great many. Marian Anderson’s outfit with the flame orange jacket, which she chose for her performance at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939, after she had been barred by the Daughters of the American Revolution from singing at Constitution Hall because she was black. A slim handmade tin box that protected the freedom papers carried by Joseph Trammell, a former slave emancipated in the 1850s. Shards of stained glass found by civil rights activist Joan Mulholland in the gutter outside the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, after it was bombed in 1963 by white supremacists. A racket used by tennis champion Althea Gibson, who in the early 1950s was the first African American to compete in the U.S. Nationals and Wimbledon. Tiny shackles made to be worn by a slave child.

The curators say their job will never be done. They continue to collect items attached to history as it happens, from the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri, after a white police officer killed an unarmed black man, to the eventual end of President Barack Obama’s two terms.

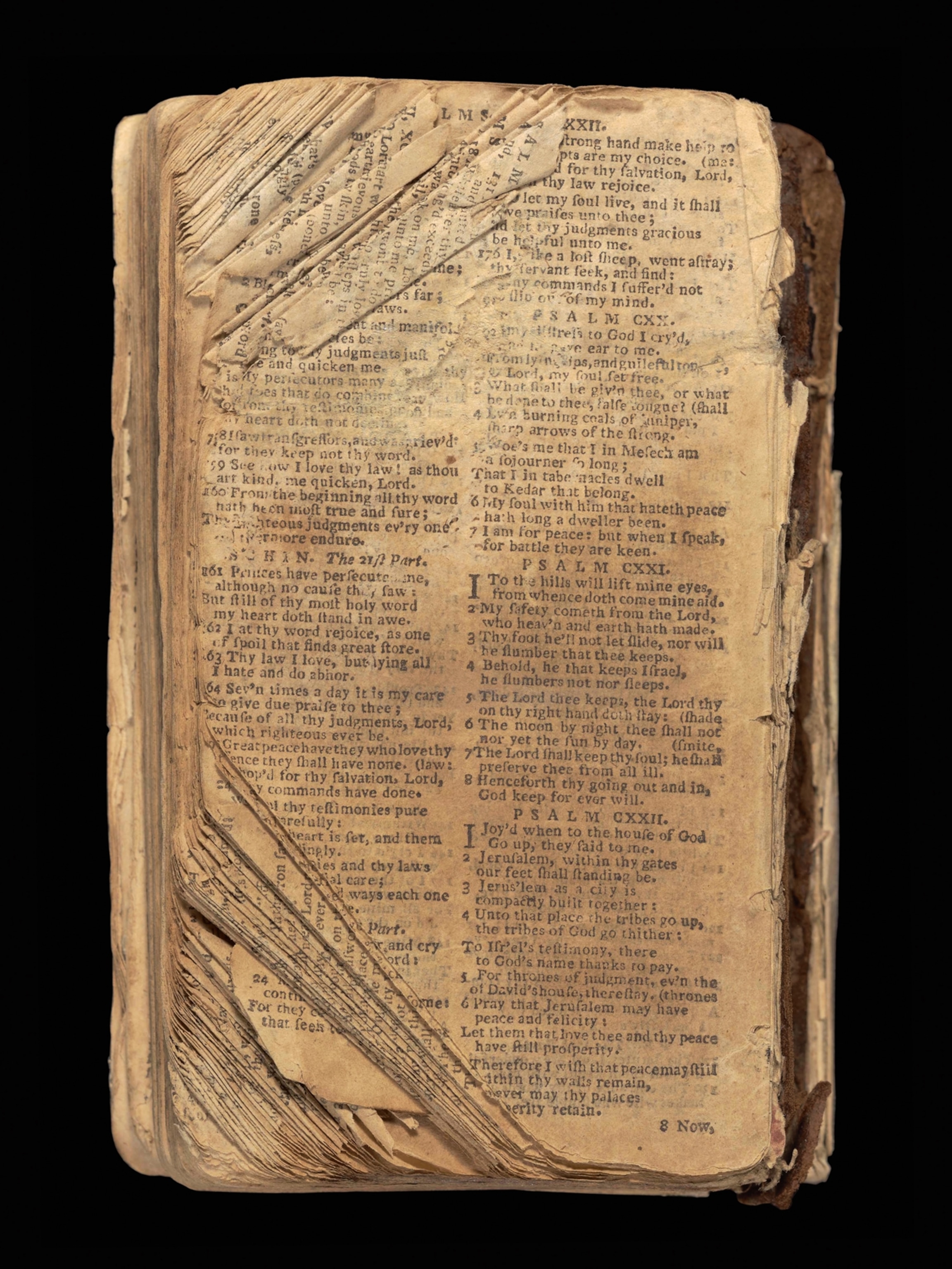

One of the most extraordinary ordinary items has a direct link to the dark chapter when blacks were bought and sold as property. It also is a reminder of how enslaved blacks desperately clung to the hope for freedom.

Rex Ellis remembers the day he was walking down a hall and overheard a colleague casually mention that a persistent woman kept calling to say she had Nat Turner’s Bible. Ellis stopped so quickly he spilled the soft drink in his hand. “Give me the number,” he said. He called her immediately but was leery. The curators were getting used to dead ends and people looking for a payday or instant attention.

The swampy stretch of Southampton County, Virginia, where Turner led a bloody slave revolt in 1831 was a short drive from where Ellis grew up. He had heard rumors about Turner memorabilia handed down among white families. A hat. A sword. A coin purse allegedly made from Turner’s skin after he was hanged.

The Bible, if it truly existed, would be central to Nat Turner history. Turner had been a widely sought after preacher and a deeply religious man who believed he had visions and received signs from God. He had taught himself to read and carried a Bible when he delivered sermons or baptized enslaved men and women. He may have carried it as his slave posse went from plantation to plantation, freeing slaves and killing at least 55 white people, including women and children.

The museum wanted artifacts that represented historic milestones but would reveal those stories in a personal way.

The persistent caller was Wendy Creekmore Porter, an adjunct women’s studies professor at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia. The Bible belonged to her stepfather, Maurice Person, a great-grandson of Lavinia Francis, who survived the raid when the family’s slaves hid her from Turner’s band.

Ellis overheard that conversation just as Porter was growing tired of “pestering.” “I was starting to think they were not interested,” she says.

When Ellis arrived at Porter’s home in Virginia Beach, the Bible was sitting on the dining room table, wrapped in an old dishcloth. Missing both its covers, with fragile, dog-eared pages, it was about the size of a dime novel. “It was so small,” Ellis says, “and that’s when I knew this could be real because Nat Turner kept his Bible close to his person, in a pocket.”

The Bible has made an incredible journey. It sat in a courthouse evidence drawer for more than 80 years until 1912, when it was given to Lavinia Francis’s grandson, Person’s father. It spent decades displayed on a family piano. Eventually it was wrapped in the dishcloth and tucked in a closet and later placed in a safe-deposit box. Porter carried the Bible to a fifth-grade classroom for show-and-tell and, in 2009, to PBS’s Antiques Roadshow in Raleigh, North Carolina, where experts were unimpressed.

“It didn’t deserve to be in the house. It deserved to be in a much greater space to tell the story,” Porter says. “A place where people can see it. A place to heal.”

Nat Turner’s great-great-great-grandson, Bruce Turner, believes the Bible’s travels have ended in the right place. “The more people can see the Bible,” he says, “the more the Nat Turner story would be spread out.”

Placing any object within the walls of the Smithsonian amplifies its significance. It is a cultural imprimatur, a way of saying: This matters. It is fitting that the National Museum of African American History and Culture is opening when the phrase “Black Lives Matter” has burst into the American lexicon. The essence of the museum’s mission is to help all visitors who walk through its doors understand that black lives and black history do matter.

It’s a message meant for all of us, particularly those who don’t know their own history. Five decades passed before Gina McVey learned about her grandfather’s military service. When he died in 1968, he was found alone on a park bench in New York City. He had been beaten. Now millions will learn about the heroic role he had in American history.

The African-American story has been treated as an afterthought, an asterisk, relegated to one month a year—and the shortest month at that. But as the nation continues to debate its core values, this history has potent lessons to teach us.

Bunch, the museum’s director, has been making this case since he first joined the Smithsonian in 1978. “If one wants to understand the notion of American resilience, optimism, or spirituality, where better than the black experience? If one wants to understand the impact and tensions that accompany the changing demographics of our cities, where better than the literature and music of the African-American community?” he says. “African-American culture has the power and complexity needed to illuminate all the dark corners of American life, and the power to illuminate all the possibility and ambiguities of American life.”

There is nothing about the new museum that suggests an afterthought. The asterisk has become an exclamation point.

A Hundred Years in the Making

1915 The Committee of Colored Citizens forms to assist black veterans visiting Washington to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Civil War. Its mission later expands to create a permanent commemoration in the capital—“a beautiful building suitable to depict the Negro’s contribution to America.”

1929 President Herbert Hoover appoints black leaders to plan a “National Memorial Building,” but no money is ever appropriated.

1967 The Smithsonian opens a museum of black history and culture in Anacostia, a storied African-American community in Washington.

1968 Jackie Robinson, who broke baseball’s color line, and writer James Baldwin ask Congress for a “commission on Negro history and culture.”

1981 Congress authorizes the National Afro-American Museum in Ohio, which runs without federal funds.

1986 Tom Mack, a black Washington tour bus operator, launches a campaign for a museum on the mall.

1988 Congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis introduces a bill for a museum. He does so every legislative session until it finally passes in 2003.

1990 To develop a plan, the Smithsonian sets up the National African-American Museum Project.

1994 Senator Jesse Helms kills Lewis’s bill: “Every other minority will give thought to asking the taxpayers to pony up for a special museum for them.”

2001 Congressman J. C. Watts, Jr., and Senator Sam Brownback, both Republicans, join Lewis, a Democrat, to help push the legislation. Watts, an African American, had worked with Lewis before. Brownback says the idea to support a museum came to him in church as “divine intervention.”

2003 President George W. Bush signs legislation to establish the museum.

2006 A site near the Washington Monument is selected.

2008 The museum begins collecting “African-American treasures” across the U.S.

2012 At the groundbreaking President Barack Obama says the museum “should stand as proof that the most important things in life rarely come quickly.”

2016 The National Museum of African American History and Culture moves into its striking new building.