On a hilltop in northeastern Tanzania, high up in the Usambara Mountains, memories are tangible things. Modernist buildings litter the lush jungle. European trees and medicinal plants, affixed with Latin labels, mingle with local species. Scientific instruments and a fully stocked library are poised for use.

This is what’s left of the Amani Hill Research Station—a past vision of the future, suspended in time. It’s also what brought Siberian photographer Evgenia Arbugaeva to East Africa two years ago. Her aim? To document the nostalgia that lingers here and create images that “bring back the atmosphere of this dark, magical place.”

Arbugaeva worked closely with Wenzel Geissler, an anthropologist at the University of Oslo. For the past several years, he and his team—an international consortium of scientists, historians, and artists—have been studying old research stations in the tropics. Their project examines the memories, perceptions, and expectations of those who used to live and work at these postcolonial scientific sites.

Yet Amani is not a ruin. A staff of 34—elderly watchmen and maintenance workers, a librarian, a few lab attendants—still lives there in the shells of houses, many without water or electricity. Some say they’re waiting for the site to be revived.

“Amani stands for the dreams of science and progress bequeathed upon colonial populations,” says Geissler. “When funding dried up here in the early 1980s, dreams did too. But hypothetically it’s all there to be switched on again. In these buildings—in these people’s memories and dreams—the idea of a potential future lives on.”

Amani was founded in the late 19th century as a German botanical garden and coffee plantation. After World War II it became a British malaria research institute. Since 1979 it’s been operated by Tanzania’s National Institute for Medical Research, which pays the current staff to maintain the site for future use.

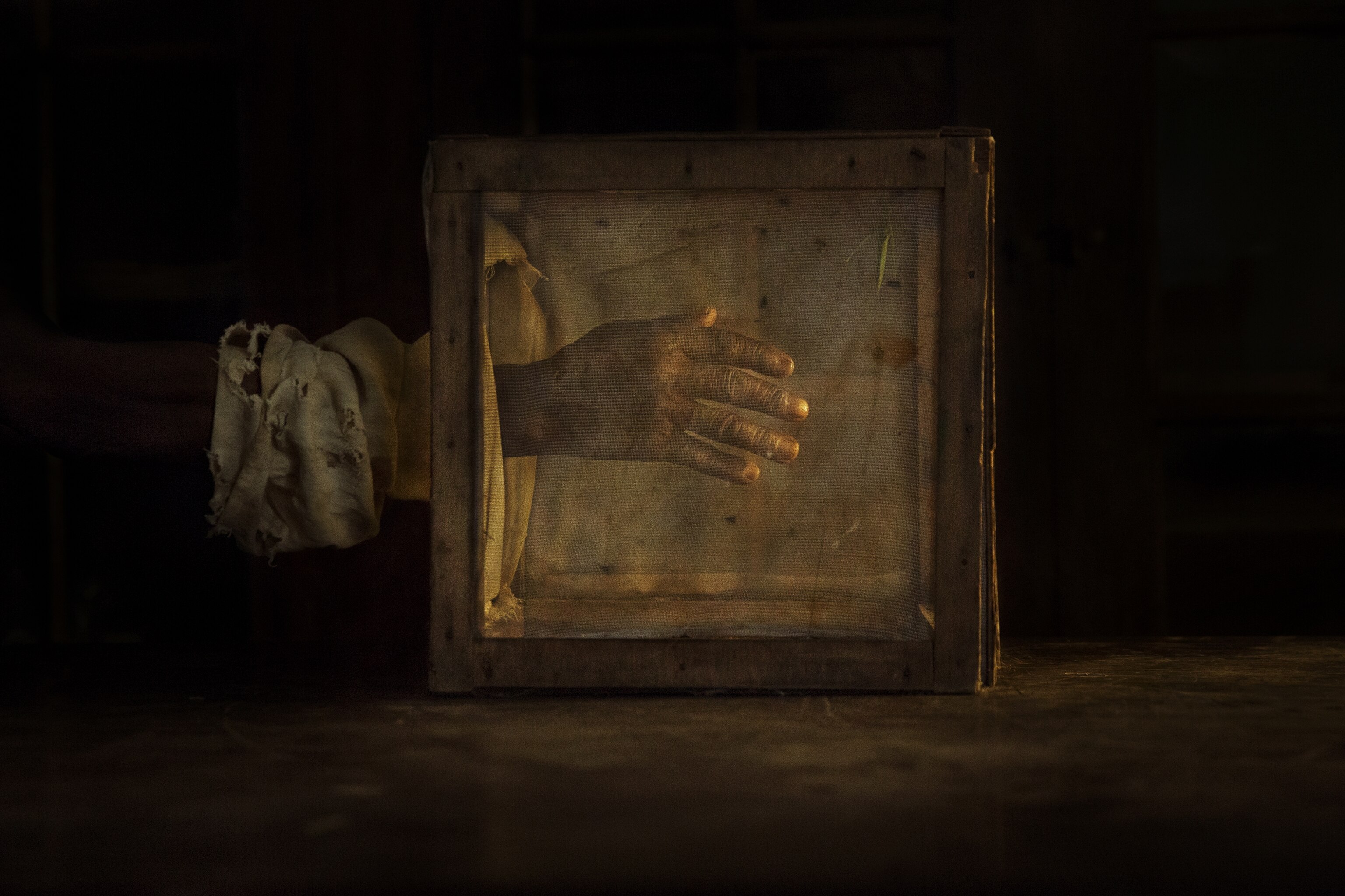

To “channel the spirit, motion, and beauty of the place” as it stands today, Arbugaeva spent a lot of time in the past—“in the library, amid all the dusty old books on natural history and diseases, reading by candlelight.” She also shadowed John Mganga, a retired lab assistant.

“He loved to tell me stories,” she says. “And to dream—to imagine what the people who used to work there are doing. He loves the idea of being part of something bigger, part of science. He’s still connected to Amani. And he still misses it.”

Geissler says collaborating with Arbugaeva was invaluable because she was able to turn workers’ memories of old routines and rituals into images. “That helps us read the traces of a once ordered past—this idea of progress in a landscape that seems like it’s only ruins and loss,” he says. Her photos capture a sense of “shared nostalgia for … a modernity we never quite reached.”

Arbugaeva agrees. “I want people to see what I saw: a hidden world that existed before and that still exists in memories. Somebody’s still dreaming about it. I want to bring people there.”