Return to the Arkansas Delta

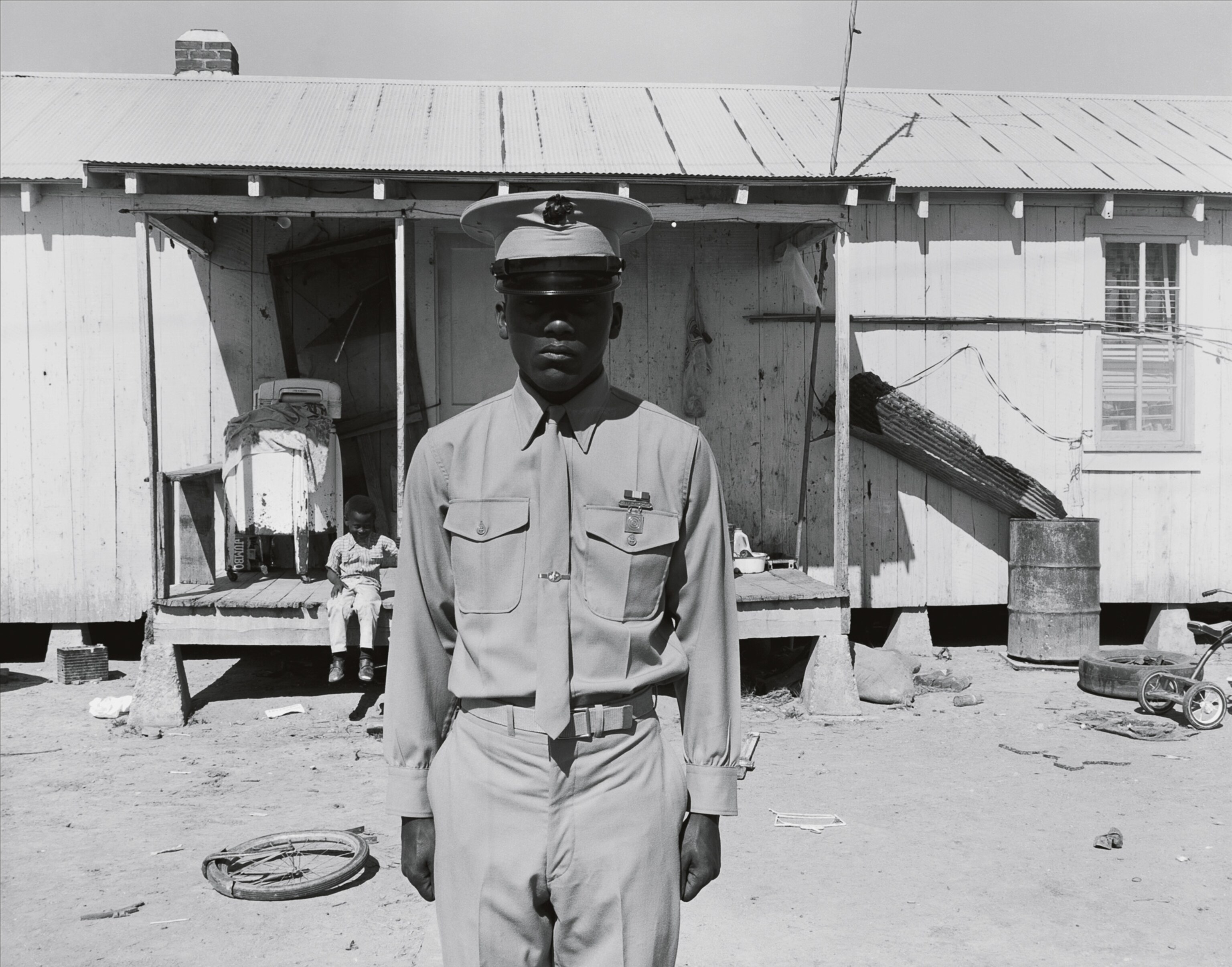

The delta west of the Mississippi River was once a place where sharecroppers lived in segregation and poverty yet forged a vibrant community. Industrial farming has erased their culture, leaving behind endless sky and few people. Eugene Richards documented their world four decades ago. Now he returns to where his pictures began.

A flashback strikes, and the photographer is once again walking across the field as our car drives down the two-lane road in the Arkansas Delta. “It had to have happened close to here,” he says, and looks out the car window with sad eyes. Beyond the plowed ground are the remains of a sharecropper’s shack that has been made irrelevant by the mechanical revolution of the past 70 years. “I’m walking with Dorothea across a plowed field to visit some people who lived in that shack,” he says in his soft voice. “And then a crop duster sees me, sweeps down, and empties his tank of chemicals on us. She really gets drenched.”

He stops. The woman who was with him at that moment became his wife. She later got breast cancer, and he always wondered if that shower of chemicals had something to do with it. The sun is bright, wisteria gone wild is climbing roadside trees, its lavender flowers hanging 40 feet in the air. The air is fresh with April, a hint of rain, and the stands of forest roar with spring. At dawn low clouds scud over the land, then the sun comes on, and the world begins again.

“That’s it. That’s all I can remember about that day.”

The photographer is a white man who had come from Boston to the small town of Augusta during the civil rights era of the late sixties, and he now believes it was the most important time of his life. He was with VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), working in a day-care center for black and white kids, and it wasn’t long before his presence seemed to unsettle the white population of the town. His name is Eugene Richards, and because of an incident one night all those years ago, much about those days and nights is beyond his reach.

Memory comes and goes here on the delta, mainly goes.

The Arkansas Delta is a series of river basins that empty into the Mississippi from the west: the St. Francis, the White, and the Arkansas. Various agricultural systems have been tried here—slavery, sharecropping, industrial farming—all producing wealth for a handful amid widespread poverty. The ancient forests have been cut, many towns have dwindled into ghosts, and yet there is this one thing: The place still beckons, captures the heart, and persists like the blues songs that grew out of the pain and the rough-edged Saturday nights.

There are soft reasons for hope on the delta: the sentimental tug of the light at dawn, the scent of violent growth in the remaining woods, the lazy movement of the rivers across the pan of dirt. But none of this makes up for a hard history of poverty, lynchings, and an out-migration into cities because of a rejection by the delta itself.

The delta is the soul of the South, a place always becoming a New South and yet always shrouded in its past, a place that gave the nation the blues and harbored the Ku Klux Klan and in the sixties was a cauldron of social change that boiled up in young black people and spilled over to young white people all across the country. Now it is a vast agricultural machine that has swept clean the land, that seems to hardly need people or towns.

Eugene Richards falls silent. We drive on. The flashback fades, the land remains, the place of the great river and the phantom chords of American memory.

The soil here is some of the most fertile in the world, but that has not been enough. Sixty million years ago the Gulf of Mexico extended all the way to Missouri. As the sea gradually withdrew, multiple rivers remained, including the Mississippi and its tributaries, which laid down deposits of deep soil, richer than dreams. Some 12,000 years ago the Ice Age ended, the glaciers melted, the rivers rose, and then came flood after flood, blanketing the delta of the mighty Mississippi. Annual flooding continued to build up the region’s loamy, alluvial deposits, which measure a hundred feet deep in places.

American settlers arrived in the Arkansas Delta around 1800 and confronted a place of forbidding forests amid swamps, a different landscape from what you see today. A few decades later, as forests were cleared and swamps drained, the delta became a promised land. The plantation system took hold, though Arkansas generally lacks the big Greek Revival mansions of the movies. There simply wasn’t enough time: The big plantation houses were just getting built here when the Civil War changed everything.

This chapter of Arkansas Delta history is written on the streets of Cotton Plant, a town of 649 people. In 1846 a man named William Lynch came over from Mississippi, threw up a house and store, and tried growing something relatively new for these parts. King Cotton began its reign. By then the Arkansas Delta was experiencing a period of dramatic growth. Steamboats on the Arkansas rivers could easily transport cotton to markets down in New Orleans. The state’s estimated annual per capita income was $68—three dollars more than the national average. Slavery is what made the growth possible. By the outbreak of the Civil War some delta counties had more blacks than whites.

Today on Cotton Plant’s main street the old Presbyterian church melts like wax in the sun. In front of the police station are two public benches, both chained. Old men sit in the shade by the dead downtown. “There used to be a veneer plant, and it ran 24 hours a day,” one old man told me. “Now everyone that works has to go somewhere else.”

I am searching for the site of the Elaine massacre, an event that began in a hamlet called Hoop Spur, three miles from the town of Elaine. In late September 1919 black sharecroppers held a meeting at a church in Hoop Spur to discuss how to get better prices for their cotton. The emancipation of slaves had destroyed the plantations’ source of free labor and replaced it with the sharecropper system. After the Civil War newly freed slaves thought they could work as tenant farmers here and escape the repression of Dixie. That worked for a while.

There was gunfire at the sharecropper meeting, and when it ended, a deputy sheriff was wounded and a railroad security officer was dead. For days afterward mobs of whites roamed with guns and hunted blacks in the thickets. U.S. Army troops were called in and may also have done some killing. Whites called it a black insurrection; blacks called it a massacre by whites. No one agrees on the tallies. Perhaps five whites were killed. Estimates run from 20 into the hundreds of black men, women, and children dead. The bottom line: This is one of the largest race killings of blacks in U.S. history, but most people today have never heard of it. I stand in a field where Hoop Spur used to be. There are only plowed ground and rows of plants. Nothing in the fringe of trees tells tales of those days.

Maybe that is best. Things move on. Or maybe the past can be forgotten but not erased.

The slaughter of the forests on the Arkansas side of the Mississippi River lagged behind the felling of ancient hardwoods on the east side. Not until the early 20th century did lumbering turn the delta into a moonscape of level fields. The towns along the lower White River and its tributaries beckoned sawmills and a fistful of woodworking factories. The town of Helena was a factory floor for lumber and wood veneer in the 1920s. It was an early booster of the dream of an industrialized New South that never came to pass.

In the 1940s and ’50s, thanks to the King Biscuit Time radio show, Helena became the broadcast center for blues drifting across the delta. Juke joints boomed on Walnut Street, and whites secretly listened to the blues of Muddy Waters, Robert Nighthawk, and James Cotton on the radio. Then came the civil rights victories, and whites pulled their kids from integrated schools.

Now Helena-West Helena is a collapsed place—the final blow came on July 9, 1979, when Mohawk Rubber closed and took the last fat payroll with it. But there is an effort to make the town a cultural center, a shrine to the blues. Abandoned buildings say the place is over. The blues festival says it may come back. The morning light, the passing people who all say hello, the green vines that seem to devour all the work of human beings, the Mississippi River that licks the levees—these things insist that life goes on.

The photographer is not sure what happened. Eugene Richards was at his boardinghouse. There may have been a beating, he thinks. Maybe it was because two of his black female co-workers lived in the same boardinghouse he did. The only thing he knows for sure is that he ended up with seizures, possibly from a blow to the head, and was sent to a psychiatric hospital in Texas. When he spoke to his white landlady years later, she said she had caught someone pinning Ku Klux Klan crosses to the boardinghouse’s gate but hadn’t wanted to worry him.

There were other incidents: his dog, Mange, shot to death; lug nuts removed from the wheels of his girlfriend’s car; a gun pulled on him and some black friends at a café; his face cut by a big white man with razor blades as Richards came out of a black church one Sunday. Two young VISTA volunteers were beaten bloody with broken coffee cups in a restaurant in nearby Hughes. The assailants reportedly thought the men were Richards and a co-worker.

Responding to the abject poverty and racial violence he’d witnessed, Richards joined with other former VISTA volunteers, including a couple from Iowa named Earl and Cherie Anthes, to start an antipoverty organization called Respect, which published a tiny newspaper, Many Voices. Richards began to photograph the changes taking place. He covered Klan rallies, the aftermath of race killings, black people running for office.

Now the black-and-white photographs are what remain of his time there. There is a fog over those years in Arkansas. The blow to Richards’s mind left shards of recollection separated by huge gaps, little fragments that drift up without warning, such as the memory of him crossing a plowed field with Dorothea, the woman who would become his wife and whom he would photograph as she succumbed to the cancer that would kill her.

In 1944 at the Hopson Plantation across the Mississippi River, an innovation in agricultural practices would have far-reaching effects on the Arkansas Delta. For the first time, an entire crop was harvested using a mechanized cotton picker, thereby ushering in an era in which one machine could replace more than a hundred hands doing brutal work in the fields.

This led to a second wave of the Great Migration, an exodus in the forties and fifties and sixties of more than five million blacks escaping poverty and illiteracy and discrimination in the Arkansas and Mississippi Deltas and the rest of the South for what they hoped was the true promised land of urban life. Showing the way was a sharecropper turned blues musician named Big Bill Broonzy, who had left Arkansas for Chicago in the 1920s and sang of his leavetaking in “Key to the Highway”:

I got the key to the highway,

And I’m billed out and bound to go

I’m gonna leave here runnin’

’Cause walkin’ is most too slow.

Everything here seems timeless, and yet all the changes came fast. By 1970 the sharecropping world was already disappearing, and the landscape of today—huge fields, giant machines, battered towns, few people—beginning to emerge. Today one person can farm 38,000 acres with only a dozen farmhands.

But the delta has something going for it that the rest of the nation has yet to fully learn. It is a place where race is always out on the table in plain view and is sometimes honestly discussed. A growing number of people here realize that the problems of the future won’t be mastered unless race is put behind them—unless building communities with work, decent wages, and justice for all is put at the top of their agendas.

Gertrude Jackson is in her late 80s and spent her life on the delta. She’ll take now over then. Especially since then was hard work with a hoe and the handcuffs of segregation: “As long as you don’t have to go into the fields, it is a good day.”

In the late sixties a utility pole outside her house near Marvell was shot at when she worked to end school segregation. Later she founded a community center. “When I was a kid, people didn’t talk about the Elaine massacre. When civil rights people came, I heard about it.” She has gray hair, wears black slacks and glasses. In her soft voice she says, “When you make up your mind to do something, you don’t have any fear.”

Ten of her 11 children have left—for Los Angeles, Virginia, Memphis, Baton Rouge, Georgia, the military: “There just wasn’t anything here to do, so they went out.” What is striking about her: She hasn’t forgotten her struggle, but she seems to live in a state of grace without wounds.

Cherie Anthes and her husband, Earl, the former VISTA volunteers with whom Richards worked at the newspaper, never left the delta. She is a retired public health nurse; he still works in community development. They live in a world they think has hit bottom, and in that fact they find hope. Earl thinks the divisions between whites and blacks, between owners and workers, don’t matter anymore, because unless things get better for everyone, then it’s over for everyone.

Olly Neal is part of the past and the future. He is 71. In the early seventies he was a firebrand, a Vietnam vet and black organizer who carried a gun in self-defense, the guy who led a boycott of white businesses in Marianna and ran a VISTA-organized health clinic there. Now most of the stores downtown are closed, the factories gone. There are only a couple of juke joints in the whole county. Neal is a retired appellate judge who once worked in the courthouse in Marianna, which faces a square with a statue of Robert E. Lee.

Neal has hope. He cultivates the young, has sent a dozen locals to college. He believes they will someday return and fix the place.

Eugene Richards remembers Neal as one who inspired him but told him to leave the delta in the early seventies, said it was time for civil rights to be a black movement. It helped Richards realize his time was up. We are sitting in Neal’s office when I mention this conversation. Neal snaps alert, looks over, and says, “Gene, was that you I told to go home?” and he gets up, and they embrace. Talk turns personal and emotional.

Neal and his brothers slaughter a steer each year for a barbecue. Gene must come down for this, he must. But for Richards, returning is complicated. In part because his time in Arkansas is still the burning core of his life. And in part because he left dispirited and confused about whether he’d accomplished anything at all. Now, 40 years later, the sharecropper life that he documented has slipped away. The place is less poor than it was and less rich at the same time. Whatever the South is, it stays with you, and whatever the delta is, it beats as the heart inside the South.