Beyond Taste Buds: The Science of Delicious

Taste receptors, volatiles, gustatory cortex: There’s more to yum than you might think.

Julie Mennella, a biologist who studies the sense of taste in babies and toddlers, often records her experiments on video. When I visited her recently at the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, she showed me a video of a baby in a high chair being fed something sweet by her mother. Almost as soon as the spoon is in the baby’s mouth, her face lights up ecstatically, and her lips pucker as if to suck. Then Mennella showed me another video, of a different baby being given his first taste of broccoli, which, like many green vegetables, has a mildly bitter taste. The baby grimaces, gags, and shudders. He pounds the tray of his high chair. He makes the sign language gesture for “stop.”

(Kiki or Bouba: What Is the Shape of Your Taste?)

Human breast milk contains lactose, a sugar. “What we know about babies is that they’re born preferring sweet,” Mennella said. “It’s only been a couple of centuries since the time when, if you didn’t breast-feed from your mother or a wet nurse, your chance of survival was close to zero.” The aversion to bitter foods is inborn too, she said, and it also has survival value: It helps us avoid ingesting toxins that plants evolved to keep from being eaten—including by us.

Food or poison? Vertebrates arose more than 500 million years ago in the ocean, andtaste evolved mainly as a way of settling that issue. All vertebrates have taste receptors similar to ours, though not necessarily in the same places. “There are more taste receptors on the whiskers of a large catfish than there are on the tongues of everybody in this whole building,” Gary Beauchamp, another Monell scientist, told me, indulging in a little hyperbole. Anencephalic infants, who are born with virtually no brain beyond the brain stem—the most primitive, ancient part—react to sweetness with the same joyful-seeming facial expressions I saw in Mennella’s video. The broccoli grimace is also primitive. In fact, although our tongues have just one or two types of receptor for sweet, they have at least two dozen different ones for bitter—a sign of how important avoiding poison was to our ancestors.

Food or poison? Vertebrates arose more than 500 million years ago in the ocean, and taste evolved mainly as a way of settling that issue.

The challenge many of us face these days is different: It’s the pleasure we get from food that gets us into trouble. The modern food environment is a tremendous source of pleasure, far richer than the one our ancestors evolved in, and the preferences we inherited from them—along with a food industry that’s increasingly adept at selling us what we like—often lead us to adopt unhealthy habits. Yanina Pepino, a nutritional scientist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, told me that she once watched a child on an airplane add sugar to Coca-Cola—an option that wasn’t available to australopithecines.

Our preoccupation with food has led to a boom in research on taste. It has turned out to be a very complicated sense—more complicated than vision, said Robert Margolskee, director of the Monell Center. Scientists have made great progress in recent years in identifying taste receptors and the genes that code for them, but they are far from fully understanding the sensory machinery that produces our experience of food. Margolskee described it to me as “one of these Rube Goldberg devices in which the little ball rolls down and activates this thing, which activates that thing, and there are about six different steps, and then a signal travels to your brain, and you either swallow what you’ve got in your mouth or spit it out.”

Almost 25 years ago my wife introduced our daughter’s Brownie troop to the “tongue map,” which she’d learned about in a cookbook when she herself was a girl. Each of the basic tastes, she explained, is perceived by taste buds in a unique region on the tongue: sweet at the tip, salty and sour at the sides, bitter at the back. She gave the girls Q-tips and bowls of salt water, sugar water, and other liquids, and invited them to prove it to themselves.

“I can taste everything everywhere,” one of the girls said.

“No, you can’t,” my wife said. “Try again, and really pay attention.”

“I can taste everything everywhere too,” said another girl.

As it happens, the Brownies were right, and their leader was wrong. It’s true that in some people the receptors for particular tastes may be more concentrated in certain areas on the tongue, but all of them are found all over, and a Q-tip dipped in lemon juice will seem sour no matter where you dab it. (The receptors sit on the surface of taste cells, which are bundled together in taste buds.) The notion that each taste has its own tightly circumscribed detection zone can be traced, according to Linda Bartoshuk of the University of Florida, to a 1942 misunderstanding by a Harvard professor of a paper published in Germany in 1901. The tongue map wasn’t definitively debunked until the 1970s, and many people still believe in it, even though it takes only seconds for seven-year-olds to disprove it.

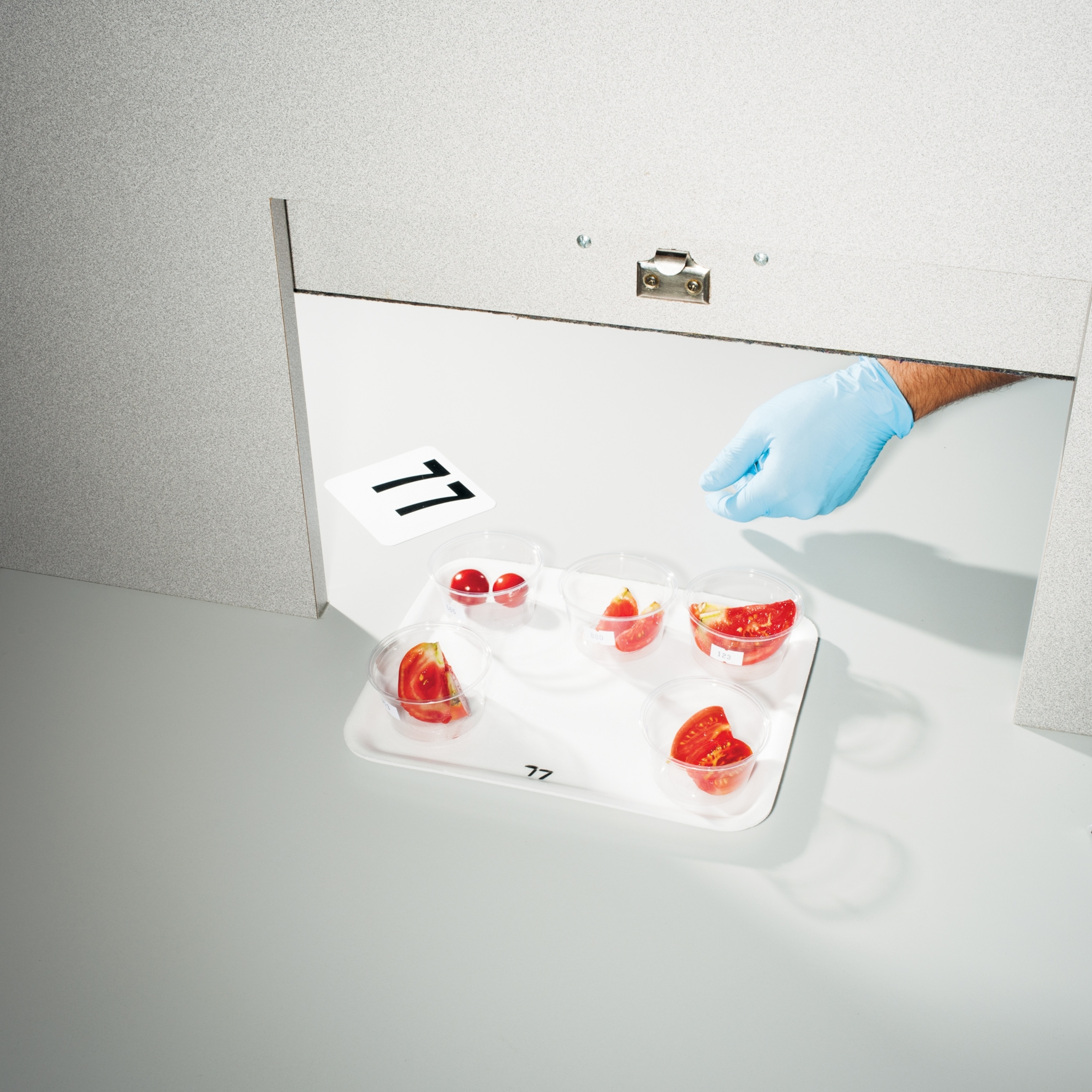

Aristotle counted seven basic tastes: the four known to my daughter’s Brownie troop, along with astringent, pungent, and harsh. Nowadays most authorities agree on five: the Brownie four and umami, which was first described by a Japanese scientist a little over a century ago. It’s the mouth-filling savory taste created or enhanced by things like soy sauce, aged beef, ripe or cooked tomatoes, and monosodium glutamate. More recently researchers have proposed at least half a dozen additional basic tastes. Fat and calcium are among the leading candidates—both are believed to be detected by receptors on the tongue—but there’s no consensus yet.

Taste receptors alone don’t produce tastes; they have to be connected to taste centers in the brain. In recent decades scientists have discovered receptors identical to some of those on the tongue in other parts of the body, including the pancreas, intestines, lungs, and testes. We don’t “taste” anything with them, but if, for example, we inhale certain undesirable substances, the bitter receptors in our lungs send a signal to our brains, and we cough.

As animal species have evolved, they’ve sometimes lost tastes that their ancestors possessed. Cats and many other obligate carnivores, which eat only meat, can no longer detect sugars. (When cats lap milk, they’re responding to something else—probably fat.) Most whales and dolphins, which swallow prey whole, have lost almost all taste receptors.

Something similar may have happened in humans. At Monell a scientist named Michael Tordoff handed me a plastic medicine cup containing a clear liquid and asked me to drink it. It tasted like water. He said, “You didn’t taste much of anything, but this is something that rats and mice prefer to almost everything else we have ever, ever tested. If you give a rat a bottle of this and a bottle of sugar, it will drink more of this.”

The brain pays attention to whether you’re sniffing or chewing and swallowing, and it doesn’t treat those signals the same.

The liquid contained maltodextrin, a kind of starch that’s a common ingredient in sports drinks. If a human athlete takes a mouthful of maltodextrin solution and immediately spits it out, Tordoff said, the athlete will perform better, despite having tasted and ingested nothing or next to nothing. “I don’t have a good explanation,” he continued. “There’s something very special about starch that we don’t understand. It may be there’s a separate receptor for it or one specifically for maltodextrin. But the receptor is no longer plumbed into the conscious parts of the brain.”

Although the tongue map doesn’t exist, there may be a taste map in the brain. A region called the gustatory cortex has been reported to contain clusters of neurons that are specialized to respond to individual basic tastes. Signals from the tongue reach them after passing through the brain stem, and in the gustatory cortex, or maybe along the way, they become part of a complex and only partially understood experience that we commonly call taste but should really call flavor. Linda Bartoshuk told me that only a small part of our experience of food comes from our taste buds. The rest is really the result of a kind of backward smelling.

You can demonstrate this to yourself with candy. If you pinch your nose shut and chew, say, an anonymous-looking white jelly bean, your tongue will register immediately that it’s sweet. That sweetness comes from sugar, and it’s the jelly bean’s primary taste. Let go of your nose, though, and you’ll immediately perceive the flavor: Ah, vanilla. Conversely, if you pinch your nose shut and put a drop of vanilla on your tongue, you won’t taste anything, because vanilla has no taste—only a flavor you can’t detect with a pinched nose.

When we chew, swallow, and exhale, Bartoshuk explained, “volatile molecules from the food are forced up behind our palate and into our nasal cavity from the back,” like smoke going up a chimney. In the nasal cavity they bind with odor receptors—and it’s those receptors, of which humans have somewhere between 350 and 400 types, that are the main source of what we perceive as flavor. That’s different from taste, which is the sensation derived from our taste buds, and it’s also different from ordinary smelling, because the brain distinguishes between odors we sniff through our nostrils (orthonasal olfaction) and odors that reach our nasal cavity from behind as we eat (retronasal olfaction)—even though the same receptors detect both.

“The brain pays attention to whether you’re sniffing or chewing and swallowing,” Bartoshuk continued, “and it doesn’t treat those signals the same. Odor information from retronasal olfaction goes to a different part of the brain—the one that also receives information from the tongue. The brain combines retronasal olfaction and taste, creating what we call flavor, although the rules of integration are not well-known.”

Jelly beans can be props for another trick too, Bartoshuk said. Releasing your nostrils when you’re chewing one doesn’t just tell you what the flavor is; it also makes the jelly bean taste sweeter—an effect that’s not caused by sugar, which contains no volatiles and therefore has no effect on smell receptors. The explanation, she said, is that other ingredients of a jelly bean contain volatile molecules that somehow “enhance the sweet message,” making the brain think the jelly bean contains more sugar than it does. Such sweetness enhancers are common in fruits, maybe because producing them costs less energy than producing sugar and yet they’re just as effective at attracting insects and other pollinators and seed dispersers. “Strawberries have something like 30 volatiles that enhance sweet,” Bartosuk said, “and when you put all the signals together, you realize that a substantial amount of the sweetness is coming from their interaction in the brain.”

That effect occurs even though the enhancers themselves aren’t sweet. Bartoshuk and her colleagues have isolated one from tomatoes that “has the smell of dirty socks.”

Life without retronasal olfaction can be unpleasant. Barb Stuckey, the chief innovation officer of Mattson, a food-and-beverage development firm in California, was once approached by a woman who’d lost her sense of smell in a car accident. Her sense of taste—the taste buds on her tongue and their connections to the brain—seemed to be intact, but nothing tasted good anymore, because the connection between the odor receptors in her nose and her brain had been severed. She was missing most of the flavor of everything she ate. “She was in arbitration with the person who’d hit her,” Stuckey told me, “and she needed to prove that she was disabled. That was a challenge, because she looked fine.”

To help the woman demonstrate her impairment, Stuckey cut up a plain rice cake—one of those Styrofoam-like disks of puffed white rice that are as close to tasteless and flavorless as food gets—and seasoned the pieces with a mixture of standard reference compounds for all five basic tastes: sugar (sweet), table salt (salty), citric acid (sour), pure caffeine (bitter), and monosodium glutamate (umami). All those compounds are essentially volatile free and therefore have no effect on odor receptors. “I sent the rice-cake pieces to the woman and told her to give them to the arbitrators and explain that this is what everything tastes like to a person who has no sense of smell,” Stuckey said.

She offered me the same experience, and I put a piece of rice cake in my mouth and chewed. The seasoning created a mildly complicated and slightly chemical sensation on my tongue, as I experienced the five basic tastes all at once. But because there were almost no volatiles, I perceived very little flavor, and nothing that made me want to reach for a second piece. “That’s what every meal is like for her now—pizza, lobster, whatever,” Stuckey said. “Can you imagine?” The woman won her case.

Most culinary schools don’t teach students how to taste before they start to cook ... But how can you possibly start an education around food without the building blocks of flavor?

Remarkably, people who’ve lost just their sense of taste take even less pleasure in eating, even though taste buds make a relatively small contribution to flavor. The main reason seems to be that if the taste receptors on the tongue aren’t functioning, the brain mostly ignores input from retronasal olfaction. Stuckey thinks the basic tastes also create a flavor’s “structure.” “I think of these as the girders, the steel beams,” she said. “There are foods out there that, without the bitterness that occurs in them naturally, would taste really flabby and flat and one-dimensional. Tomatoes, for example.”

In addition to her duties at Mattson, Stuckey teaches a course at the San Francisco Cooking School called “The Fundamentals of Taste.” “Most culinary schools don’t teach students how to taste before they start to cook,” she said. “They jump right in with, like, knife skills. But how can you possibly start an education around food without the building blocks of flavor?” She and her students do an exercise in which they make barbecue sauce. Most of the ingredients she provides are ones you would guess: tomato sauce, tomato paste, sugar, honey, liquid smoke, paprika. But there’s also a tray of ingredients whose predominant taste is bitter: coffee, cocoa, tea, bitters. “It’s not really intuitive, because you don’t think of barbecue sauce as bitter, but if you taste it before and after you add a bitter ingredient, you realize that bitter changes the whole gestalt. It adds a complexifying note.” At home Stuckey uses soluble espresso—instant coffee—as a bitter complexifier for many dishes, and especially for sweet or sweetish sauces.

Mattson’s research laboratories contain a lot of high-tech testing equipment, but in one of them I met three researchers who were chewing thoughtfully and staring into plastic cups. A food manufacturer had hired Mattson to replicate a spicy brown-rice dish sold by one of its competitors, and chemical analysis could take the folks in white lab coats only so far. “The human palate is the most sophisticated analytical device there is,” Stuckey said. “You have to put it in your mouth.”

In the late 1980s Linda Bartoshuk, who was on the faculty at Yale at the time, identified what she called supertasters—people whose taste buds are so numerous and so densely packed that they experience the basic tastes with uncommon intensity. That’s not all good: Supertasters get more pleasure from the foods they like than ordinary tasters do, but they also dislike more foods, especially strong-flavored ones. At Monell I got a vivid demonstration of how different a supertaster’s experience can be. After Michael Tordoff gave me a sip of maltodextrin, a geneticist named Danielle Reed (who’s married to Tordoff) had me drink a second clear liquid in a plastic medicine cup. Again I tasted nothing.

Hakan Ozdener, a colleague of Reed’s, happened to walk past her door. She called to him and handed him a cup of the same solution. Almost the moment it touched his lips, he winced, then looked as if he’d taken a swig of gasoline.

“It’s PTC,” Reed said. “Phenylthiocarbamide. Seventy percent of Caucasians are taste blind to it, but for people who can taste it, it’s extremely bitter.” And for some it’s intolerably so—Bartoshuk discovered supertasters while working on PTC. The concentration in Reed’s solution was very low, almost homeopathic, but Ozdener was still gasping. (“People are afraid to walk past my office,” Reed said.) As a bitter supertaster, Ozdener is less likely than I am to like Starbucks coffee or rapini. On the other hand, Tordoff told me later, he’s probably less susceptible to some upper-respiratory tract infections—the PTC-detecting receptor is also in the nose, where it seems to detect certain bacteria and prompt us to expel them.

For tasters of all kinds, the critical problem nowadays, Julie Mennella said, “is that we live in a food environment that isn’t like our evolutionary past.” We hunt and gather in supermarkets and restaurants, and many of the manufactured foods we buy are so energy-dense that we could satisfy an entire day’s caloric requirements with a single meal. The food industry has been attacked for loading products with ingredients we’ve evolved to crave, but when it tries to make healthier products, we don’t always reward it.

In 2002, when McDonald’s announced that it would stop frying foods in oils containing trans fats, it received complaints that its french fries didn’t taste as good—and maybe they didn’t, but some of the complaints came from cities where the change hadn’t been made yet. Cutting salt from manufactured foods is even trickier. There’s general agreement that most of us eat too much. Yet if you give consumers two bowls of soup that are identical except for their salt content, they’ll usually prefer the saltier one, and if you describe a soup to them as low in salt, they’ll generally rate it less favorably than the “regular” version, even if the two are identical. Food companies complain that if they do cut salt, they’re almost forced to do so without taking credit—they can’t promote the low-salt version the way beverage manufacturers have promoted sugar-free sodas.

And even that business is fraught. In recent years sugar has replaced fat and salt as the most vilified element of the modern diet, but replacements for it are controversial too. This year PepsiCo removed the nonnutritive sweetener aspartame from Diet Pepsi, not because scientific studies had shown it to be harmful, but because aspartame has a lousy reputation among health-conscious consumers. The new aspartame-free Diet Pepsi contains two other sweeteners, sucralose and acesulfame potassium. There’s no guarantee they’re safer.

Sugar is especially challenging, because children respond to it in ways that aren’t obviously related to taste, and almost all of them consume too much of it, at least in developed countries. “Sweet blunts expressions of pain during childhood,” Mennella said. “It will reduce crying in a baby, and it’s used as an analgesic during circumcisions and heel-stick blood draws.” (The effective agent is sweet taste rather than sugar, because aspartame works too.) A child’s response to sweetness can be so gratifying to parents that they end up reinforcing it: How many other mood-altering tricks work so quickly and so well?

But there are public health implications, and they go beyond increases in childhood obesity and type 2 diabetes. Mennella worries in particular about “baby-bottle caries”—tooth decay caused by sugar-containing beverages, including fruit juice—especially in children who are put to bed with bottles. It’s “a major preventable disease of childhood,” she said, “and it’s reaching epidemic proportions.”

Bartoshuk told me that increasing the concentration of sweetness-enhancing volatiles in certain foods may make it possible to reduce their sugar content without making them taste less sweet. But she worries about unintended consequences. “As soon as we can produce a sweet experience that has no calories, isn’t toxic, and has no nasty characteristics—what will that mean for the brain?” she said. “We know that sweetness uses neural pathways that look very much like the ones used by drugs of addiction, which are believed to hijack circuitry that evolved for food and particularly for sweet. So are we doing anything terrible? I don’t know.” Getting something for nothing looks good, she added, “but Mother Nature has a nasty side.”

Our preference for sweets may hook us in ways we don’t realize. A recent study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found a large, sudden increase in the popularity among teenagers of electronic cigarettes, in which a battery-powered heating element turns a nicotine-bearing solution into vapor, which is then inhaled. “Vaping” has helped many longtime smokers cut back on real cigarettes, but it also circumvents a strong inhibition to taking up smoking in the first place: the repellent taste and smell. In teenagers it may do that in part by exploiting their vulnerability to sweetness—some popular vaping liquids contain sucralose, and young users often add it on their own.

The good news is that our inborn taste inclinations are not immutable. People who succeed in reducing salt in their diet typically find that their tolerance for highly salted food declines. And our natural resistance to broccoli, brussels sprouts, and other healthful but bitter foods can be overcome through experience—especially if it begins early. Mennella’s research has shown that babies’ flavor preferences are affected by their mothers’ diet during pregnancy and by their own diet after birth. “Babies can learn to like a variety of foods,” she said. “But they have to taste the food in order to like it.” Her main advice to parents is to set good examples and not give up. When the baby in her broccoli video is offered a second spoonful, he still shudders—but he opens his mouth.