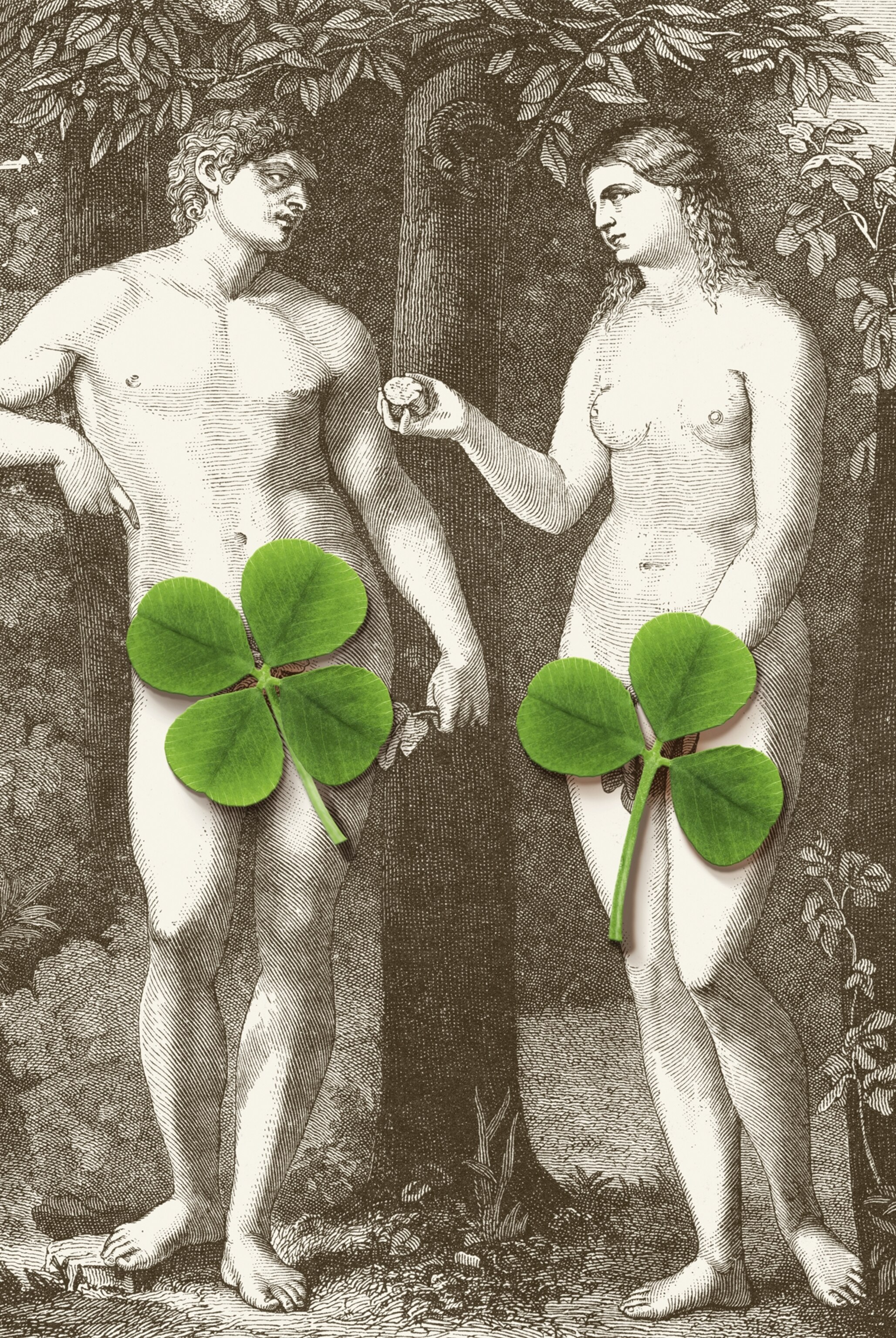

Imagine a World Where Gender Is Neither a Plus nor a Minus

Anne-Marie Slaughter famously wrote that women “can’t have it all”—but hopes for a future where all people can fulfill their potential.

Nine-year-old Mikayla McDonald of Ottawa, Canada, says: “There isn’t anything I can’t do because I’m a girl. Everyone is equal … but in the olden days everyone wasn’t equal.” Nine-year-old Alfia Ansari of Mumbai, India, says: “We won’t get education in school, but boys will be educated, and therefore they can travel anywhere, but girls can’t.” Those comments to National Geographic, in a nutshell, reflect the tremendous discrepancies in the treatment of girls and women worldwide. No country has achieved full gender equality. In North America and much of Europe, women have made such progress that girls have some reason to believe that anything is possible. But in too many other places, girls and women are still the property of their fathers or husbands, denied the food, medicine, and education provided to men.

('Women's Rights are Human Rights,' 25 years on)

Given the gulfs between us, is it possible to write about “the state of women” collectively? We do not all bear children; we do not all love men; we do not even all have the same genitalia.

But women do all at least have one thing in common: We are all prisoners of our cultures.

Historian Yuval Noah Harari, in his masterly account of how Homo sapiens evolved, explains how women can be defined not only in terms of their biological roles but also in terms of their cultural roles. As Harari describes it, females—human beings with two X chromosomes and the bodies and hormones to match—have not changed. But women—human beings who operate in society and exercise rights under law—have progressed from being the illiterate property of their husbands to being equal and educated citizens with the same rights as men under law. Though Harari’s analysis may hold true in places such as Athens, it may not be as true in Ankara, Abuja, Agra, or other places where cultural norms sustain inequality.

In my experience, biological differences are real. As the mother of two boys and the aunt of five nieces, I agree with what Chip Brown writes in “Making a Man”: Some behaviors really do seem innate. My elder son was fascinated with wheels, trucks, and construction machinery before he could talk.

But biology is not destiny, for men or women. Women are still trapped and oppressed in so many parts of the world, forced to submit to the dictates of men. But men also are trapped, forced into culturally defined roles.

Boys, Brown writes, are urged to be aggressive and tough “so they may fulfill the classic duties to procreate, provide, and protect.” Watching our sons be twisted to fit society’s expectations of men, even when those men wield power, can be as frustrating and counterproductive as watching our daughters be denied the ability to fulfill their potential.

The concept of gender fluidity remains alien, even abhorrent, to many people in Western society. But that concept is accepted in nations around the world, and it opens doors. Once we recognize that gender identity and expression exist along a spectrum, why should we cling to the rigid categorization of men and women? The ultimate goal, surely, is to let all people define themselves as human beings, to break out of assigned categories and challenge received wisdom.

In my lifetime, from the 1960s to the present, women in the United States have advanced in ways nearly unimaginable to me as a girl. I knew no women doctors, professors, politicians, engineers, or CEOs. One of my sons, by contrast, assumed during elementary school that men didn’t serve as U.S. secretary of state, because he had learned about so many women in the job. Culture is deeply malleable and changing faster than ever.

As governments and societies realize that to survive and compete they must tap the full talent of their citizens, progress toward full gender equality will accelerate. If Homo sapiens advances because of the power of our imaginations, as Harari argues, then we can imagine a world in which gender does not define a person any more than race or ethnicity does. Without the weight of gendered expectations, each of us—women and men—can “develop the full circle of ourselves,” to borrow Gloria Steinem’s lovely phrase. We can work to extend equality and opportunity to the entire human family.