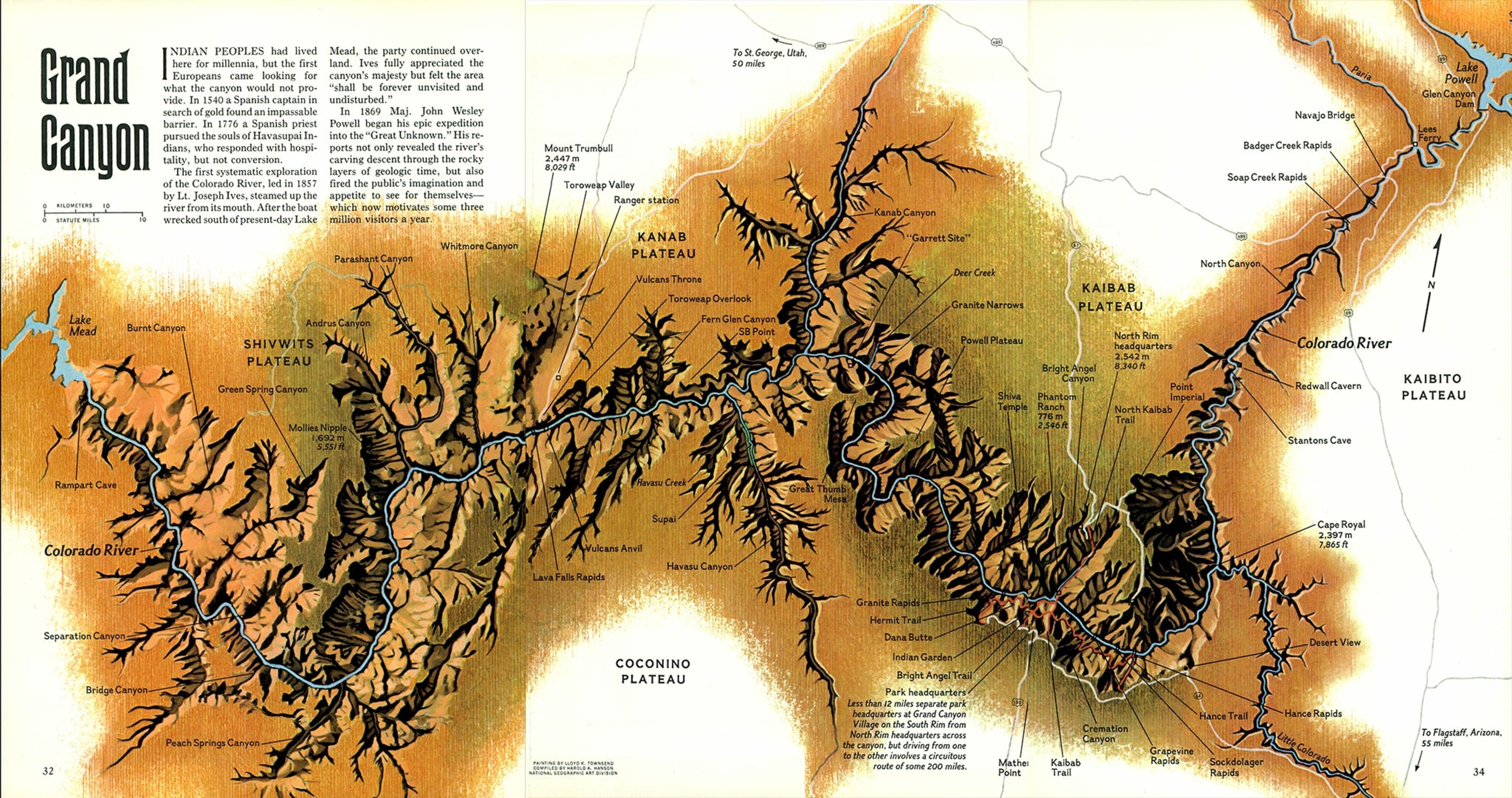

At one time everyone at Toroweap had an airplane, but that was before Merribeth came along in 1965 to marry John. Now only half the people at Toroweap have an airplane. Its name is Pogo. It belongs to John Riffey, the only park ranger there since 1942.

Merribeth and John live in a stone cabin that blends modestly into a vast solitude, atop a scree slope about ankle high on a 1,500-foot canyon wall. John casually presides over 200,000 pristine acres on the north side of Arizona's Grand Canyon National Park. For Dr. Merribeth Riffey, an ornithologist, it's a well-stocked aviary.

The Riffeys have no neighbors. The few visitors usually come by way of St. George, Utah, turning right off Route 389 at the park sign and driving down their 60-mile unpaved driveway.

"Only got snowed in once," John laconically volunteered. "In 1948. Didn't want to go anywhere anyway. Weather was bad."

Six miles beyond their cabin Toroweap Valley ends—awesomely. Where it should be, athwart its path, lies the Grand Canyon.

And nothing else. No steel guardrails, no asphalt parking lots, no manicured paths with starched rangers leading nature walks.

Your eyes ricochet up, down, east, west, north, or south and see only a unique, sublime natural spectacle.

Stand on the rim, if you dare, and you can look past your toes straight down half a mile.

Listen hard. You'll hear an insistent murmur drifting up from the tiny squiggle of a river down there. It originates as a deepthroated roar from mighty Lava Falls, considered the world's fastest navigable rapids.

At river level the Grand Canyon measures 277 miles, but up here the rim wrinkles into thousands of miles of unspoiled niches like Toroweap, where nature can be heard, seen, and smelled unmolested. Where you can take your soul for a long walk—slowly. Where the canyon experience can seep into your memory to stay warm and handy and comforting. More than ever we need our Toroweaps.

Fortunately Congress provided for them when it established the National Park Service in 1916 and ordered that the parks be managed "by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."

Preserving them is the sole responsibility of the National Park Service. Increasingly there have been charges, some formalized in lawsuits, that it's not doing it very well in the Grand Canyon.

The most unusual and important accusation is now before the U. S. district court for Arizona. The national park—literally the place itself—is the plaintiff suing the National Park Service, charging that mismanagement of river trips results in irreparable damage to the environment and the public's ability to enjoy the park. Such suits can be brought when an organization, in this case the Sierra Club, files as joint plaintiff.

To report on the park and its problems, I hiked, boated, and flew hundreds of miles in the Grand Canyon. First I went to park headquarters to meet Superintendent Merle Stitt, whose name heads the long list of defendants in the suit. He greeted me with relaxed western hospitality—on guard but not defensive. I asked if his management of the park fulfills the 1916 congressional mandate. After the briefest hesitation he answered.

"No. I'd have to say no. As the visitors increase, so do the demands for protection. So we've had to set limits on camping, hiking, and river running. We may have to set limits on how many can enter the park."

A quota? The idea disturbed me. Perhaps because when I first saw the park in 1949, as a student hoboing through the Southwest, there were no crowds. Only 600,000 visitors shared the view from the rims that year. A negligible handful of us hiked the inner canyon. Only a dozen adventurers challenged the river rapids. Only a hundred people had run the river in recorded history.

This July as many as 200 people a day will line up to take the trip. More than a quarter of a million of us hiked into the canyon last year, while another quarter of a million toured overhead by plane and helicopter. A crush of nearly three million jammed the two-lane roads and crowded onto the same overlooks I used thirty years ago. And more are coming. The United States Travel Service says the canyon heads the list of natural attractions that Americans want to visit.

Merle noted that despite its apparent hardiness the canyon's desert ecology is fragile. Overuse and ignorance, as well as malice, can damage it severely.

He told me of one group of hikers who accidentally burned a lovely oasis in Deer Creek Valley. Another party damaged Rampart Cave's iron gate, and their torches started a smoldering fire in the cave's fivefoot-thick floor of Pleistocene sloth dung. In the priceless deposit, 11,000 to 30,000 years old, were remains of extinct horses, cats, mountain goats, and birds.

Ranger Marvin Jensen, inner-canyon manager, admitted that the park wasn't adequately patrolled and had become shabby from overuse.

"Our trails are in poor shape," he told me. "They're a safety hazard to mule trips. I've only got nine full-time people, counting myself, to manage almost a million acres. That's just not enough people to do what needs to be done."

To add to his problems, as many as 12 hikers a day with more enthusiasm than endurance and good sense collapse and have to be "dragged out" of the canyon.

Mary Langdon, who's in charge of backcountry reservations, warns hikers they're entering a tough world.

"Young guys who think they're in great shape try to run down the trail and back. They find the canyon's stronger than they are. I found one guy halfway up the North Kaibab Trail lying beside a campground faucet—never saw anyone so sick—he cramped for three hours. He told me he runs ten miles a day at home, but it took him two days to recover."

Some don't recover—usually because they ignore good advice. Mary pulled a file on one young hiker. When he was found near death on July 12, 1977, on Hermit Trail, his backpack contained a set of motorcycle tools and a book on desert survival. He had already tossed out along the trail three pairs of motorcycle boots, a camp stove, and extra clothes. He hadn't wanted to risk theft by leaving the gear with his bike. He died because he hadn't carried the recommended two gallons of water.

Mary's office issues permits for 360 backcountry campsites a day. For Easter week, requests had to be submitted between October 1 and 5 to be eligible for a lottery. Only 20 percent of the requests could be filled.

Conservationist Rod Nash, speaking at a park symposium, stated the problem simply: "We're loving the Grand Canyon to death. We must protect it from its friends."

One early friend of the canyon, President Theodore Roosevelt, contributed to the destruction of its ecology by ignoring his own sage advice. After visiting the canyon in 1903, he delivered an eloquent and spontaneous tribute:

"In the Grand Canyon, Arizona has a natural wonder which, so far as I know, is in kind absolutely unparalleled throughout the rest of the world .... Leave it as it is. You cannot improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it. What you can do is to keep it for your children, your children's children, and for all who come after you, as one of the great sights which every American ... should see."

Three years later he declared the canyon a game preserve, and gave it national monument status in 1908. He returned in 1913 for a mountain lion hunt—a popular sport that eventually pushed the animal to the brink of extinction on the Kaibab Plateau.

With its major enemy decimated, and a ban on nonpredator hunting, the mule deer soared in numbers from an estimated 4,000 in 1906 to 100,000 in 1924. They munched through meadows and forests with the efficiency of a plague of locusts. By 1924 deer were starving by the thousands. The prepark balance has never recovered.

Nor will it. It would be something like Humpty-Dumpty putting himself back together while all the king's men stomped on him. Because the children's children for whom Roosevelt wanted to save the canyon are here. We're hiking and boating through the park with a Malthusian vigor that Roosevelt couldn't have anticipated. We wear heavily on the trails, the ecology, and each other's tempers.

Over the years people have come who feel they can "improve on" the Grand Canyon. In 1889 a railroad was planned to run the length of the canyon at river level.

A huge interfaith chapel was almost begun in the 1950's; it would have seated 350 people facing into the canyon from the South Rim. Hydraulic jacks would have lifted Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish accoutrements from the basement as needed.

In 1961 the Western Gold and Uranium company proposed building a hotel on their South Rim mining claim that would cascade 18 stories down the wall—offering a canyon view from each of its 600 rooms.

A Phoenix group, in 1974, wanted to build a tramway from rim to floor so that more people could enjoy the wilderness.

Arizona Congressman Bob Stump submitted a bill last year to revive the plan for a Hualapai Dam, which would flood fifty miles of the western Grand Canyon.

Despite Roosevelt's wish that there not be "a building of any kind ... to mar the wonderful grandeur," a suburb of shops, motels, and tacky government housing and facilities sprouted just back from the South Rim to cater to the ever growing crowds.

Now neither these facilities, the Park Service, nor the park itself seems able to cope.

For decades the "parks are for the people" policy meant satisfying demands for recreation. This left superintendents to stick their fingers in cracks in the environmental dikes to prevent floods of damage—usually with hands tied by lack of funds and a public ignorance of ecology. Growing awareness of ecology and pressure from environmental groups are changing the priorities. Superintendent Stitt told me, "If I err in the balance between recreation and conservation, it will be on the side of conservation."

To ease river congestion, the park staff has suggested more people take winter trips. That's what I was doing when the Glen Canyon Dam stopped me.

A group of us had been on the river two weeks and were about to run Lava Falls Rapids when a computer turned off the water. Its microminiaturized brain—programmed to see the river only as a force to spin turbines—closed the faucets in Glen Canyon Dam, which control the Colorado River's flow into the canyon. The reservoir level and power demands were down, and conserving water seemed the right move.

For a hundred people floating down the river on Easter vacation, it wasn't.

Marvin Jensen later told me, "Some of them we helicoptered out, and some came as far as Phantom Ranch and hiked out. That was after we got the Bureau of Reclamation to kick us some water to sluice them on down to there."

When California's summer heat has air conditioners gasping for electricity, the flow from the dam peaks at 30,000 cubic feet per second. In late March we were getting only about 900—not enough to get us over Lava's boulders intact.

Park Scientist Dr. Roy Johnson and I had planned to attend a boatmen's seminar starting in three days on the South Rim. We were stranded on the same side of the river and only fifty miles away, but to get there—if the water didn't rise—we would have to cross the river, climb 3,000 feet to Toroweap Valley, bum a ride to the highway, and drive 200 miles. From Navajo Bridge on the park's east side to Hoover Dam at Lake Mead, 300 highway miles to the west, the only way to cross the canyon is by footbridge at Phantom Ranch.

Host of our small river party was Ron Smith, owner of Grand Canyon Expeditions. In hundreds of trips he had never seen the water so low. Since we had no contact with the outside world, Ron hiked out of the canyon to check on the water.

While Ron was gone, Roy held an impromptu seminar. The fickle dam that delayed our plans, Roy told us, was also altering the river's ecology for centuries to come.

"The clear, cold flow we get now won't sustain most of the pre-dam native fish. The Colorado River squawfish, a member of the minnow family that can weigh as much as one hundred pounds and reach six feet in length, will soon be extinct here—if it isn't already. They used to say the river was 'too thick to drink, too thin to plow.' Now it's a trout stream."

Witness the 12-pound rainbow John Craighead landed a few days earlier. Avid fishermen in our group removed the barbs from their hooks and pulled in and tossed back hundreds of trout. One trout tagged in Lake Mead reportedly was caught at Lees Ferry. Unknown in the previously wild and muddy river, trout thrive in clear water, eating the eggs and fingerlings of resident fish.

As Roy talked, he sifted beach sand—pulling out bits of charcoal and other human debris. A five-year study concludes that the annual swarms of 14,000 river runners are damaging the canyon—perhaps not irreparably but certainly enough to diminish its enjoyment for future visitors.

At flood stage the river used to flush detritus and plant life downstream and deposit new beaches. Now thick stands of tamarisk, an invader, congest the shorelines, and trash is collecting at an amazing rate on overused beaches. Also piling up on the beaches, an esthetic and health problem, is most of the twenty tons of fecal matter produced by river passengers every year.

"Some of the beaches here are as messy and cluttered as a kid's sandbox," Roy complained.

The river study confirms that boat motors bother some visitors. Not only do they "mask the natural sounds," the study claims, but they also impede communications between boat operators and passengers—preventing safety warnings. Commercial motorboat operators counter that the motors do no damage and permit them to carry more people faster, cheaper, and more safely than oar-powered trips.

When the Colorado ran free, an average of 380,000 tons of silt passed the gauging station at Phantom Ranch every day. During a 1927 flood, 27,600,000 tons were recorded one day. Now there are about 40,000 a day, and no major floods. The rest is collecting in Lake Powell. The water no longer deposits sand but slowly hauls away beaches already there. Since the reduced flows can no longer clear debris brought down side canyons, rapids will get worse.

At Phantom Ranch, 90 miles upriver from Lava, I had talked with another Roy. Roy Starkey works for the ranch. He used to work for the U.S. Geological Survey.

"For 20 years I took water samples and checked flow and temperature every day," he said. "But I lost my job to a satellite."

An automatic "fish" now tests the river every morning. A solar-powered radio transmits the data directly to a weather satellite over Brazil, which relays it to a Virginia receiving station, which automatically telephones it to the Geological Survey computer at Reston, Virginia, for processing.

All of this happens each morning faster than Roy can turn off his alarm clock.

Rob Smith returned to our river camp to report that the water wouldn't come up for several days. Roy Johnson and I decided to pack out.

Fortunately for us, one of the few escape routes out of the canyon starts just above Lava. It follows a gully in a near-vertical 3,000-foot slope of loose black volcanic cinders. Under summer sun the surface temperature may reach 200°F. In March it was no problem, except that at times it was like going up a vertical treadmill. The trail seemed determined to slide to the river faster than we could go up. The slope continued on 600 feet above the Toroweap Valley floor to form a textbook-perfect volcanic cone called Vulcans Throne. A series of eruptions some 10,000 years ago formed the cone and nearby lava cascades.

Volcanism was no stranger to the canyon here: At several intervals beginning more than two million years ago, lava poured into the chasm, forming dams as high as 2,300 feet—high enough to create a lake reaching back beyond Lees Ferry, 179 miles upstream. The last lava dam, 80 miles long and perhaps 800 feet high, blocked the river about 250,000 years ago.

After each dam was created, the lake would eventually breach the top of the black barrier and the river would resume its grinding search for sea level, slowly wearing down and clearing the dam away.

Our trail finally led us to the Riffeys' back door, and they took us in like the waifs we were. John Riffey knew, but avoided, our trail: "They say that slope sits at the maximum angle of repose, but sometimes it doesn't repose."

We told John we had to get to park headquarters. But isolation at his remote station for nearly four decades—he's two years beyond normal retirement—has encouraged a certain irreverence.

"Now why would you want to do that? You won't like it. They used to take us over there every year to try to civilize us, but they finally gave up on that."

John drove us back to the trail head that night to check on Ron. He had planned to join us but hadn't shown up, and a storm was lashing the area. Blasts of sand tattooed exposed skin. We reached Ron by radio, safe—so to speak—down on the river. That night, wind gusting at 80 miles an hour flattened two tents.

The next morning broke clear. I wondered what had happened to the storm.

John knew: "Went back for another load of sand."

Could John fly us to the seminar?

"I can't, but Pogo could. 'Cept he doesn't like it over there either—too crowded and he doesn't have a radio. He'll be glad to fly you around here though."

It seemed like a good idea until we started to get in. Pogo, an old two-passenger Piper Super Cub, is 26 going on 50. I asked about a bulge on the front of the wing. "Guess he's getting arthritis."

OK. But what about the box of mouse poison John had just pulled out of the wing?

"Oh, Pogo's just made of light metal and cloth. Last time he went in for a checkup, they pulled three mouse nests out of his wing. Sometimes I hear them running around in there. 'Fraid they might chew up something important."

Pogo's reliable, but a loose spark plug had once caused the engine to cut out briefly over the canyon. "It was OK," John said. "My hair was already gray."

John tied the window up against the wing with cotton clothesline so I could take pictures. Pogo twisted and dipped up and down the valley and the canyon like a teenager on a skateboard. We passed the pine forests of Mount Trumbull, which peaks at 8,029 feet, and were eyeball-to-rim with SB (for Son of a Bitch) Point at 5,600 feet. Pogo circled around Mollies Nipple at 5,551 feet before dropping to river level so I could photograph rangers on a burro study.

After landing, John replaced the poison.

John was right about the South Rim. The congestion was a shock after Toroweap. My reservation at the El Tovar Hotel had been given to someone else. There was a two-hour wait for dinner. A television in the lobby entertained guests.

Before coming to the canyon, I had talked with Barry Goldwater, Senator from the Grand Canyon State. He had a plan to improve the South Rim.

"I'd like to see everything—the shops, hotels, restaurants—moved five miles back from the rim, even if it means tearing down that wonderful old El Tovar Hotel. That would be as far as you could drive. Electric or steam buses would take you from there."

He had winced at his suggestion to tear down the El Tovar and thought better of it. "I'd be willing to leave it but not as a hotel."

When the rambling log chateau was opened in 1905, it offered the latest in elegance, including electric lights. Recent modernization—which includes signs in Japanese—keeps it the Ritz of Grand Canyon accommodations.

The Park Service has no plans to move the El Tovar, but it does hope for an expanded public transit system that could replace some of the private cars on the South Rim. That's the only point on which its plan for the South Rim agrees with Goldwater's. The Park Service's more moderate ambitions include moving most parking lots and commercial operations back from the rim a bit and tearing down the worst eyesores as they become obsolete—all by the year 2000.

Everyone agrees something should be done, and many would support Goldwater's plan to hasten the obsolescence with a bulldozer, but he's not optimistic. "I don't think the Interior Department has the guts to face up to the resistance it would encounter."

The Senator can be forgiven if he feels possessive. He's been going to the canyon since he was 7—three years before Teddy Roosevelt's death. He first walked to the bottom of the canyon in 1919 when he was 10, the year the canyon was deeded national park status. Thirty-eight years ago he became the 70th person to run the river.

He and Congressman Morris Udall sponsored bills that almost doubled the park to its present 1,218,375 acres in 1975.

Ironically, a decade earlier both had sought to back up the river in the added areas with the Marble Canyon and Hualapai Dams. A tenacious battle led by the Sierra Club stopped construction. Now both men are opposed to dams in the canyon. Goldwater admits that of all his Senate votes, the one he most regrets was the one for Glen Canyon Dam.

I retreated from the crowded hotel lobby to the overlook from which I had first seen the canyon. I've seen it often since. The magic never fades. But like a first love the first visit can never be repeated—and nothing can prepare you for it.

Forested slopes leading to the rims give no warning. As you walk the last few feet, the world suddenly slides away, leaving you hovering uncertainly over a forbidding abyss. It's as if nature has carved a monument to itself—a majestic phenomenon that hushes all but the most insensitive.

Gravity pulls at your soul. Your mind reaches for something familiar. Distance, depth, and time seem infinite. You sense more than see an opposite rim far away.

In gaudy rock layers the skeleton of the earth lies exposed. Without being told, you know that down there lie answers to questions about the birth of the earth.

Light and shadows flow among towering buttes in perpetual slow motion with no two moments alike—ever. When the weather's at its worst, the drama's at its best. Afternoon storms fester around sun-warmed buttes and rumble from valley to valley. Lightning stabs at the peaks—sometimes in crisp white thrusts, sometimes as flickers behind curtains of mist.

The spectacle frightens some people. I watched a Japanese lady tiptoe to within a few feet of a protective wall, lean forward, gasp, and back away. Mothers clutch children's hands. Men shorten their stride. For some people a quick look, a snapshot or two, and they want out.

Several of Roy Johnson's river researchers spoke at the seminar. During the past five years their study has taken on the status of a minor industry. Three dozen investigators from twenty institutions have fed data into computers. The goal—a management plan that would strike a delicate balance between maximum river recreation and minimum damage.

Now the recommendations are on record. Like a suitor not quite suggesting marriage—yet—the Park Service has issued a draft of the plan, with a notice that it has been neither approved nor disapproved.

But if the public says yes after a series of hearings, the recommendations will become policy within a year. Many may anyway if the Sierra Club suit now pending goes against the Park Service.

The plan recommends doubling the user days (one person on the river for one day), lengthening the summer season from three and a half months to six months, and establishing a six-month winter season. It would also raise the ratio of private trips from 8 percent of the total to 30 percent, and phase out all motors over a three-year period, resulting in longer, quieter trips.

Since each passenger would consume more user days, the overall result of the changes would be a 10 percent reduction in the number of commercial passengers.

All human feces, 40 tons per year if the user days double, would have to be containerized and carried out of the park.

One destructive park visitor we all meet along the riverbanks abides by no quotas. The bristly, clever, beloved, obnoxious little African burro—once a valued domestic pack anima–survived the prospectors who brought him a century ago. Now wild, or feral, he has prospered at the expense of the park—eating vegetation, trampling archeological sites, and carving an eroding network of trails. Some say he drives out native residents, most notably the rare desert bighorn sheep.

Since 1924 some 2,600 Equus asinus have been shot by the Park Service, and it once intended to keep on until "all" were gone. A 1976 report estimated "all" to be between two and three thousand. A year later another study indicated only 300. This confused the issue but didn't lessen the pressure.

Ever since Jesus rode a burro into Jerusalem, the animal has enjoyed a special status. A blizzard of emotional "save the burro" letters made burro-control ranger Jim Walters an instant villain.

Secretary of the Interior Cecil Andrus responded to the letters by delaying further action until accurate statistics and more proof of damage could be gathered.

The proof, an intensive study, will cost about $1,000 for each of the estimated 300 animals. The average will go down during the two-year project because the population will go up—to about 400—since man is the prolific burro's only predator in the park.

I joined a team of rangers assigned to determine the practicality of flying burros out by helicopter. After considerable effort, three burros were shot with an immobilizing drug. Two died. The other, slung in a cargo net, was whisked away at great expense.

In another experiment, cowboys rounded up 12 burros from one of the more accessible areas. At auction in Phoenix the animals brought an average of $11 ahead. It had cost $450 a head to round them up. The experiments convinced the Park Service that there's still only one practical solution—the burros must be destroyed.

"This isn't a park, " lamented Walters. "It's a damn burro pasture."

The problem helped convince the staff it was running a billion-dollar business, with millions of customers, while uncertain of the quality or quantity of its assets—especially in the 600,000 acres acquired in 1975. Another 390,000 acres may be added.

An unusually frank introduction to a 2. 8-million-dollar inventory and resource-management plan complains that resource-management funds have been nil in the past and are still inadequate. It admits that years of neglect of the park are apparent. It regrets that pressure groups know more about the park's resources than the staff itself and spotlights staff inadequacy by stating, "At best there are only four or five people on the staff that would recognize a Peregrine Falcon (one of our endangered species) if they saw one."

A ranger who would is Chief of Resource Management Dave Ochsner, godfather of the elaborate project.

"We have to remember this is one of the seven natural wonders of the world, and manage it accordingly. People come from all over the world to see it."

He invited me to join him and Park Anthropologist Dr. Robert Euler on a two-day inventory of Cremation Canyon with mule packer Stan Stockton as guide….

A few days later I find myself high atop a stumbling mule on the precipitous Bright Angel Trail, contending with my latent acrophobia and a general distrust of mules.

The trail drops 3,000 feet down a fault line, crosses the Tonto Platform, and plunges through Granite Gorge to the river: a total vertical drop of one mile.

Stan means to be reassuring when he tells me no rider has been lost since guided mule trips started almost a hundred years ago.

"A few mules have gone over the side, but the riders have always dropped to the high side in time to avoid the long fall. "

I'm reminded of lecturer Burton Holmes's experience on a trip down Hance Trail in 1898 with several men and one woman. On the “most awful " sections he dismounted and descended in "the posture assumed by children when they come bumping down the stairs ... neither the mocking laughter of the men nor the more bitter words of sympathy from the brave Amazon could tempt me to forget that my supremist duty was to live to give a lecture on the canon."

Captain Hance, his guide, referred to him as the "lecturer who came down part way like a crab."

"Couldn't happen now," Stan says. "A quarter of a mile down the trail at 'cinch-up' point everybody stops, supposedly so wranglers can tighten girths. Anyone who's had enough is quietly encouraged to quit right there. A few do. One time a guy decided he'd had it. He asked his wife—she wasn't quitting—if she needed anything. 'Yes,' she replied, 'a new husband.'"

We are well down the trail when Stan tells this story. He has assigned me to 15-year-old

Pappy, said to be as safe as a rocking chair. And, I find, about as receptive to new ideas.

For most of his life Pappy has walked these switchbacks nose to tail with the mule ahead. When I lag behind to take photographs, it breaks his pattern. He warns me he doesn't like it with a few snorts and a nervous four-footed fox-trot.

When the rest of our group disappears from sight far below, he rears up, gets the bit in his teeth, and bolts. Before I can remember which is the high side, we are lurching and rocketing around the switchbacks like a runaway train in a Buster Keaton movie. As soon as he reaches the tail of Bob Euler's mule, he clatters to a stop.

The other guys seem to be more than a little entertained and impressed by Pappy's performance. Bob, noting that Pappy had all four feet off the ground when we rounded the last turn, nicknames him Citation.

Stan congratulates me. He says I was right not to get off. How could I with my hand welded to the saddle horn? After that episode we get along fine—when I stop for pictures, Citation goes on without me.

On a summer day as many as 1,500 people hike down the Bright Angel Trail. Millions of hiking boots and mules' hooves have ground it into an eight-mile-long sandbox.

On the trail I meet a gray-haired lady hobbling along on rented crutches. She had broken a leg stepping off a six-inch curb two days before.

Vera, 71, and Beecher Terrell, 70, left the rim at 6 a.m., walked to the river, and were returning the same day. "We move slowly, but we'll make it," Vera tells me. "We do it every year."

(This past winter Vera wrote me that she had fallen into a bandstand while doing a polka and had broken her back, but expected to be up and on the trail soon. No dragouts, these two!)

We stop at Indian Garden, a campground built around a spring, 3,000 feet below the rim. To provide shade, canyon photographer Emery Kolb 70 years ago stuck cottonwood branches in the ground like fence posts. Now a 60-foot canopy of trees shades the inner canyon's busiest campground.

Its name, Bob Euler informs me, derived from its former use. In 1882 the Havasupai who lived along the South Rim were moved into a 518-acre reservation in Cataract (now Havasu) Canyon. A few stayed here and grew corn, squash, and beans until their eviction in 1911. According to children of the former residents, President Roosevelt personally asked them to leave because "he was going to make it a park for everyone." But at least two of the Indians remained until the l 940's.

Before he became park anthropologist in 1974, Bob had worked with the Havasupai on their land-claims settlement. They considered him a friend.

"When they heard I was joining the Park Service, they were hurt," Bob continues. "They wanted to know why I was going over to 'the enemy.' I don't think they've forgiven me yet." Since they still feel the land was taken from them unfairly, they probably won't. Before the white man arrived, they hunted along the South Rim in winter and used the inner canyon for summer gardening and as a source of water.

Their canyon is considered a verdant paradise by visitors; the Havasupai saw it as a prison. The parkexpansion bill of 1975 awarded them 185,000 acres of land, 84,000 of it from the park. Various environmentalist groups objected strenuously.

When I visited the village, Wayne Sinyella, tribal chairman, told me, "The Sierra Club thought our land settlement was a Trojan horse that would spew out dams and pizza parlors in the canyon.” It can relax. "We plan tougher restrictions than the Park Service." Time will tell.

The two-day trip to Cremation Canyon added six prehistoric sites to the park's inventory and for me a new appreciation of a mule's agility. Nevertheless, on a subsequent trip with Dr. Euler I abandon Pappy for a helicopter.

Bob, his wife, Gloria, and I dismount from our Pegasus where no mule and few men have been. We camp 2,000 feet below Great Thumb Mesa's north wall on an isolated, waterless, hummocky sandstone terrace that extends for miles along both sides of the river; it's called the Esplanade. Created by marine sands and wind-formed dunes laid down a quarter of a billion years ago, the hardened sandstone has eroded unevenly into a Brobdingnagian garden of massive sculptures.

I discover curved around the stem of one toadstool-shaped masterpiece a miniature granary with its stone door lying open as if abandoned just yesterday. But here yesterdays are counted in centuries. In Europe the Crusaders were packing for their first trip to the Holy Land when an Anasazi Indian here was patting wet adobe into a vermin-proof storage cabinet for corn. The fingerprints left 900 years ago are still legible.

Bob says that the owner probably moved away about 1150 and posted no forwarding address. He may have left the door open because he didn't plan to return—but no one today is sure why.

"You're probably the first person to see this granary since he left," Bob comments. "We'll name it Garrett Site."

Officially it's Ariz. B:10:118, since Bob had already logged another 117 sites in this tenth quadrangle. But frankly, I like Bob's name better.

The christening party is attended only by Bob, Gloria, and me, but a sunset so gaudy it would embarrass a roll of Kodachrome puts a pink blush over the world, helping to make it a memorable evening.

The next day we endure a steady buzz of sight-seeing flights. They destroy our sense of isolation but leave no permanent scars on the environment.

The routes of Dr. Euler's travels through the canyon lie over his map like a net, anchored by 2,000 red dots that mark his sites. Hiking with Bob is like touring a ghost town with a doting caretaker. The faintest clue can inspire a story so detailed it repopulates the barren canyon with people from the distant past:

A vague saucer-shaped rocky depression twenty feet across becomes a blazing pit. Anasazi women roast agave plants and collect a molasses-like confection. A hunter about 5 feet 3 inches tall with long black hair and wearing a cotton poncho-like shirt skins a bighorn sheep nearby.

A palm-size shard of reddish clay in Bob's hand grows in the mind's eye into a two-foot, globe-shaped jug filled with water from a spring a mile away. Nearby, a young girl shells ears of primitive corn slightly larger than a man's thumb.

Bob interrupts my thoughts to relate how archeologist Douglas Schwartz, twenty years ago, began studying two stick figures found in a canyon cave. Each was made from a single willow shoot split and twisted into a deerlike effigy.

"We've now found hundreds in the canyon," Bob says. "The oldest, with a 2100 B.C. carbon date, we excavated in Stantons Cave in 1963."

Since the effigies are always found by themselves, the mystery remains—who left them and why? Some are speared in the torso with a small stick, suggesting that hunting parties left them as good-luck talismans.

We leave the Esplanade as we found it. Our footprints will soon fade. I hope someone in a hundred years comes upon the granary, still unmarred, and enjoys the illusion of finding it for the first time.

The North Rim always seemed a bit mysterious—like a recluse who keeps to himself. Only 15 percent of the park visitors go there. The "strip"—that chunk of northern Arizona cut off from the rest of the state by the canyon—was one of the last regions in the United States to be developed. Polygamy survived there openly until the l 950's and may still exist covertly. The tourist year on the higher North Rim lasts only seven months because of deep snows. Its Canadian climate sustains a varied and colorful alpine flora and 11 animals not found on the South Rim. One of them, the Kaibab squirrel, is indigenous nowhere else.

It's so seldom seen today that it has been put on the list of threatened species. Last October one darted in front of me on a backcountry trail. It looked more like a small silver fox than a rodent loping through the woods. Bigger than an eastern gray squirrel, it had a reddish back and a black belly, tufted ears, and an elegant white plume of a tail.

The Kaibab squirrel depends for its existence on the ponderosa pine, nesting in it and feeding on its pollen, seeds, inner bark, and mushrooms that grow on its roots. A cousin, the Abert squirrel, lives on the South Rim and is just as dependent on the tree.

It is believed that during the Pleistocene Epoch they were the same animal, living in forests that extended completely across the canyon. Then the trees, unable to adjust to the increasingly warmer and drier climate, died out. As the trees receded up to the rims, the family was split and the Kaibab branch found itself trapped in a forest surrounded by deserts.

This fed a romantic notion that animal species unknown to man might have developed on buttes isolated in the canyon. In 1937 the American Museum of Natural History welcomed the chance to find out.

They mounted an expedition to explore the butte called Shiva Temple. The project captured the public's interest. Facilities were set up on the North Rim to flash the results to the world. One newspaper speculated that dinosaurs might be found.

When the party reached the summit, they found a few Indian artifacts but no new animal species. They also failed to find the Kodak film box that had been purposely placed there for their discovery by Emery Kolb. The photographer, apparently miffed that his offer to help had been refused, had beaten the expedition to the summit.

Pinnacles such as Shiva, which help give the Grand Canyon its unique form, occur mostly on the north side of the river. They were not formed, as the Cracked Earth Society long maintained, when an uplift split the earth like a cake that rose too fast.

There's a logical explanation. Less moisture falls on the south side, and the plateau there slopes away from the rim. The Kaibab Plateau on the north slopes toward the river, dropping more water from a higher elevation and thus causing headward erosion to develop faster.

Streams, seeking paths of least resistance, often follow fault lines in the earth—as paper tends to tear along a crease. The steeper the slope of the stream drainage area, the deeper and longer the side canyon erodes, excavating vast amphitheaters and, where canyons meet, leaving behind the pinnacles.

Preston Swapp, a young packer on the 1937 Shiva expedition, still lives nearby and until recently grazed cattle on national forest land in Kanab Canyon. Last fall Swapp was forced to suspend his operation. He told me why. "The Forest Service came in and did a study. Said we were overgrazing."

"Were you?" I asked.

"No."

He maintained that the Forest Service study team had picked one of the driest periods since his father started grazing cattle here in 1906 to do its survey. Preston, a quiet, well-tanned cattleman of 64 years, said that cattle grazing was once an important industry here, but is now dying out. Upper Kanab Canyon is being studied as a possible addition to the park.

"They're trying to run us out," Preston complained. "They're taking away a man's rights. They don't know what this country will produce. If it isn't grazed, trash plants such as black brush will take over the land. Those cattle don't compete for food with anything else down there in the canyon."

Dave Ochsner knows overgrazing can be a problem but sympathizes with Preston Swapp's problems. "These grazing operations are a way of life—they're a historical or cultural resource—a remnant of the Old West, if you want to call it that. Maybe it's a resource we should be protecting in our parks. If that way of life goes, something may fill the vacuum that won't be as good."

Preston's not optimistic. "If the land goes to the park, we'll be eliminated."

In 1540 Don Garcia Lopez de Cardenas and his small band of soldiers became the first Europeans to see the canyon. Finding no gold, they were soon on their way. For three centuries the canyon remained a mystery. Other adventurers found it an impassable obstacle, and went around.

Finally Maj. John Wesley Powell arrived in 1869, seeking neither gold nor a route west, but the canyon itself—a vast unexplored region of the United States. His Civil War rank remained his title for life, but Powell came to explore the canyon as a college professor sponsored by the Illinois Natural History Society.

He conceived the expedition, raised the money, and brought the courage and brilliance to make it a success. He also gathered together a crew of nine frontiersmen who shared his enthusiasm for adventure. They were given little chance of surviving, and, like him, none was paid.

His classic adventure tale, Canyons of the Colorado, wasn't published for 26 years—and only then to fulfill an 1874 promise he had made to Congressman (later President) James Garfield in return for the Congressman's efforts to secure appropriations for Powell's Bureau of American Ethnology.

His captivating description of the canyon—enlivened by a harrowing litany of near disasters, hunger, and desertion—has made the book a basic reference work in any river-trip library. But it wasn't essential when I ran the river with Martin Litton—he seemed to have it memorized.

Like a latter-day Powell, Martin has become something of a legend among river runners. And like Powell, he also challenges the river in little wooden boats and has influenced the development of this area. As an evangelist for the environment, the powerfully built outdoorsman was one of the leaders in the successful fight to stop construction of the Grand Canyon dams in 1966. He still approaches anyone he suspects of trying to damage our natural wonders like a Billy Sunday cornering a sinner in New York City's Hell's Kitchen.

All canyon river trips leave from Lees Ferry at the northeastern corner of the park. To reach it, we drove across miles of barren desert. Martin lamented its condition.

"When Kit Carson passed through here in the 1860's, the land was protected under a rich mat of native perennial grasses. Overgrazing by sheep has removed not only the grass and its soil-binding roots, but now, as you can see, the topsoil as well."

The Geological Survey designated Lees Ferry Mile 0 on the river for map purposes whether you go up- or downriver. If you go upriver to Mile 12, you encounter the Glen Canyon Dam; go downriver to Mile 240, and you will enter the still waters of Lake Mead—after making the most dramatic white-water river trip in the world.

We found the boat landing paved with river rafts—giant, aluminum-colored sausages—in varying states of inflation. A passenger waiting for his ship to fill wandered among our little wooden dories as we packed our gear in the watertight compartments—smiling and shaking his head. "You gotta be crazy." He must not have known about Powell's boats—or then again, maybe he did!

We depart Lees Ferry with as much dignity as we can muster. Sitting two abreast, four to a boat, under floppy hats, behind sunglasses and white sunscreen lotion, and wrapped in puffy orange life jackets, we look like seven boatloads of teddy bears being rowed to a masquerade party.

During this 18-day midsummer party we'll endure hours of blistering sun in open boats, be chilled by plunging through raging 50-degree rapids, eat sand on our pork chops, and be obliged to shake our sneakers every morning for scorpions. Rain falling onto our faces will awaken us on strange, dark, rocky shores.

But no one minds the little inconveniences. Like wearing tight shoes to your wedding—by the time you get there, you don't notice them.

The rim with its clutter of civilization slowly rises out of sight and mind. Each new bend in the river strains the imagination. The river becomes an escalator to the past, dropping us 2,200 feet through an ever deepening gash that exposes the earth's oldest geologic eras. From the side of our dory we'll run our hands down the ages of time—layer by layer.

In the quarter-billion-year-old Kaibab limestone, formed by the last Paleozoic sea to cover this area, we find a fossil crinoid, a disk shaped like a Navajo shell bead. Five miles downriver our fingernails scratch a line along the Coconino sandstone—laid down as windblown dunes 25 million years before that crinoid arrived. Thirty miles into our trip we stroke glistening water-polished limestone. Soon we're walled in by it, a 500-foot-thick graveyard of sea creatures that swam into the region 300 million years ago.

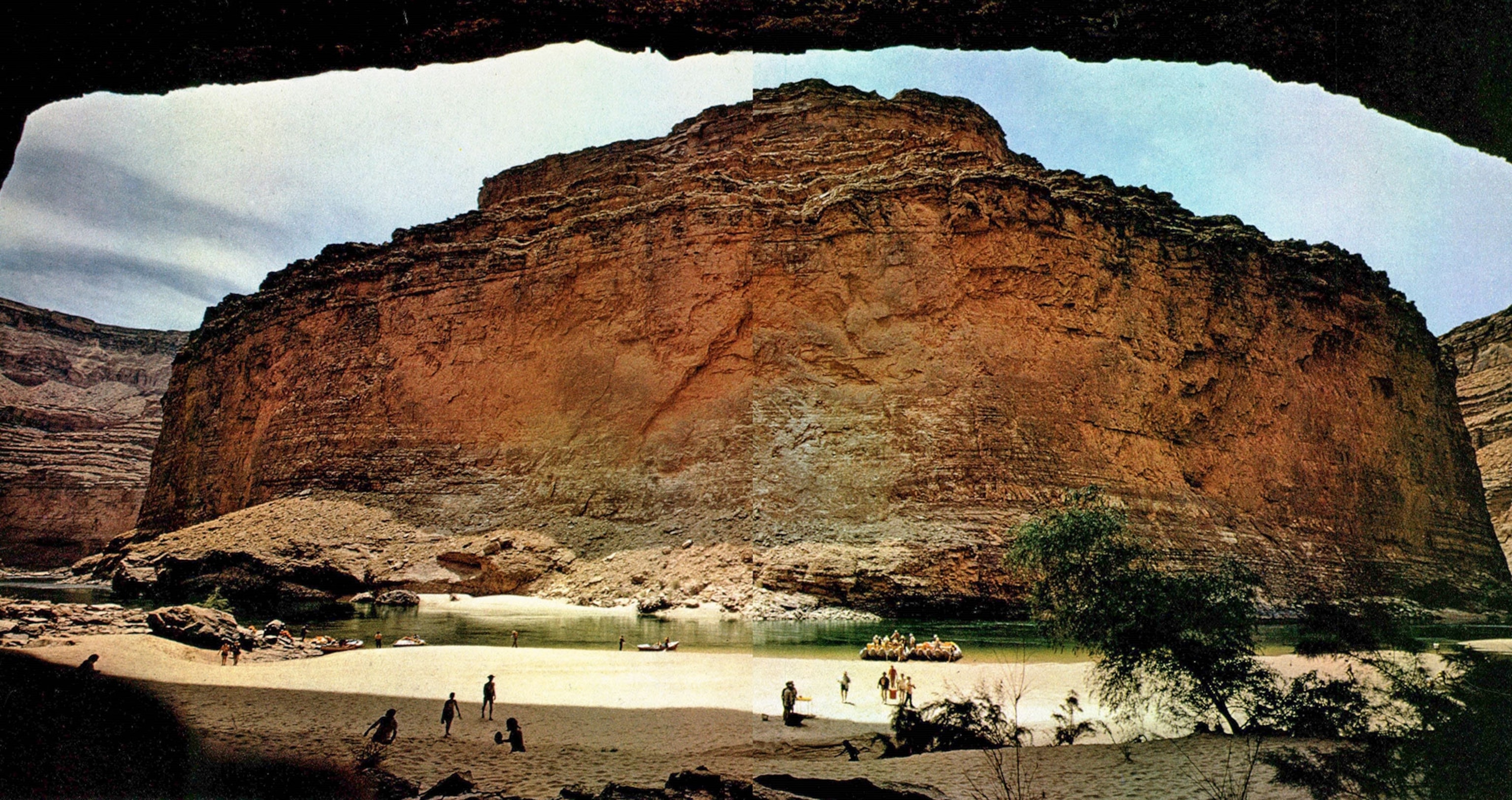

Martin calls a lunch break at Redwall Cavern at Mile 33—a huge chamber carved from this limestone layer called Redwall.

"The rock's not really red," Martin tells us. "It's gray. The iron oxide washing down from the shale stains it that color." He points to an unpainted gray scar left by a recent rockslide.

At Mile 61 the Little Colorado adds its bit to the big Colorado. It's a blue-white flow and has the appearance—and the effect, if one drinks it—of milk of magnesia.

On the sixth day we plummet down a stairstep of rapids—Hance, Sockdolager, Grapevine—until we're squeezed into Granite Gorge, a mile deep into the earth.

Streaked with pink granite, eerie fluted columns of black Vishnu schist formed about 1.7 billion years ago offer a macabre view of the Precambrian Era.

Our first rapids, Badger Creek, at Mile 8, had been easy. The story is that Jacob Hamblin, a 19th-century Mormon missionary, caught a badger here. The next rapids—more interesting—was Soap Creek. When Hamblin cooked his fat badger in the alkaline creek water, he got soap, not stew.

For two weeks our dories, all of them named for scenic wonders desecrated by man, are drawn through larger and larger rapids, each seemingly preparing us for worse to come. And always there's the old-hands' threat, "Just wait till Lava."

By Mile 178 the narrow canyon is widening again. A distant roar like a 747 jet liner revving for takeoff puts us on notice. Soon Vulcans Anvil—a tombstone-shaped slab of black basalt—looms in midriver as if to warn us away.

Just above Lava we climb the steep shore to stare down upon the awesome, terrifying spectacle. Like everything else in the canyon, Lava's better than its reputation.

Below us it sucks the river into a narrow, boulder-filled chasm, whipping it into a maelstrom of muddy froth leaping as if to escape its banks. Someone mentions that Lava has flipped more boats than any other rapids in the park.

Dale snaps a stern warning: "If there's anyone who came to see a boat flip, get away from here. We don't even want you around. If there's anyone here who says he's not afraid of this rapid, I don't want him in my boat."

Following the precedent set by Powell, who portaged Lava, a few of our group decide to walk around the rapids.

If fear is the only requirement, I am certainly qualified to ride. From above there was no scale; down here there's too much. As our dory slides down a smooth tongue into chaos, twenty-foot waves lash us. Boatman O.C. Dale yells an unnecessary, "Hang on!" Our boat thrashes like a wounded whale trying to shake a harpoon—plunging, broaching, shuddering.

The run lasts an interminable 30 seconds. That evening, Lava behind us, the teddy bears strip off the life jackets and a few inhibitions, and celebrate well into the night our smashing victory: Dories 7, Lava 0.

Sunrise comes late to the canyon floor but not without a glorious preamble. On the highest rims to the west the sun kindles a glowing tiara of light. A reflected pink blush flows down eastern walls. The raccoons have finished their nightly patrol of the camp. A family of coyotes snarl and bark as they scrap among themselves across the river. A golden eagle glides silently along a ridge, hoping to surprise a careless shrew.

In weeks spent crisscrossing the park, I often felt the cold flash of adrenaline and fear as a foothold gave way along a steep pitch. One bone-chilling mugger of a rapids stripped me of camera, hat, sunglasses, and my right boot. I suffered blisters, bruises, and a cracked ankle. I've never enjoyed a place more.

I would heal. I hope I left no scars on the canyon that won't heal, because there are a lot of people coming to see it. They should always find it unimpaired.