Have a favorite animal? There’s probably a day in its honor.

Most of us welcome a chance to celebrate. Most of us love animals. That must be why we keep designating holidays to celebrate animals—from World Bee Day to Fat Bear Week.

Ranger Mike Fitz was at the front desk of the Katmai National Park and Preserve’s visitors center in late September 2014, when he had the idea. Katmai, in southern Alaska, is known for its salmon and brown bears. In summer, fish by the ton barrel up the rivers, desperate to spawn, and bears stake out spots where they can grab and gobble up prey in order to pack on fat for the cold months to come. At certain prime fishing locations, cameras are set up to stream live video.

The “bear cams” attract a loyal online audience and generate a spirited comments section. On that late September day, Fitz was moderating the comments when he saw a diptych one viewer had posted. On the left was a “before” photo of a brown bear, slack-coated and skinny after months of hibernation. On the right was a photo of that same bear in September—it was larger by half, huge, supersize.

That gave Fitz the idea: Why not post a bunch of bear pictures on Facebook, showing the animals in their lean and enlarged states—and make it a competition? It could help answer the perennial and irresistible question: Which bear is the fattest? And, if the competition drew attention, Fitz could use it to educate people about the bears, the salmon, and the importance of conservation. So began what is now Fat Bear Week: seven days in the fall when viewers vote online, narrowing a tournament bracket of bears down to a single, corpulent victor.

Fat Bear Week could have been just another flighty example of modern humans’ weakness for declaring holidays—that propensity to fill every square on the calendar with commemorations, observances, recognitions, or declarations of a National Day of Something. But since its debut, the competition has become an internet sensation. Online participation has grown exponentially. In 2020, more than 600,000 votes were cast, and many major media publications ran articles about it.

Why has Fitz’s brainchild distinguished itself among thousands of holidays? For one thing, Fat Bear Week is funny. And once levity gets people’s attention, the holiday encourages them to show animals some real love.

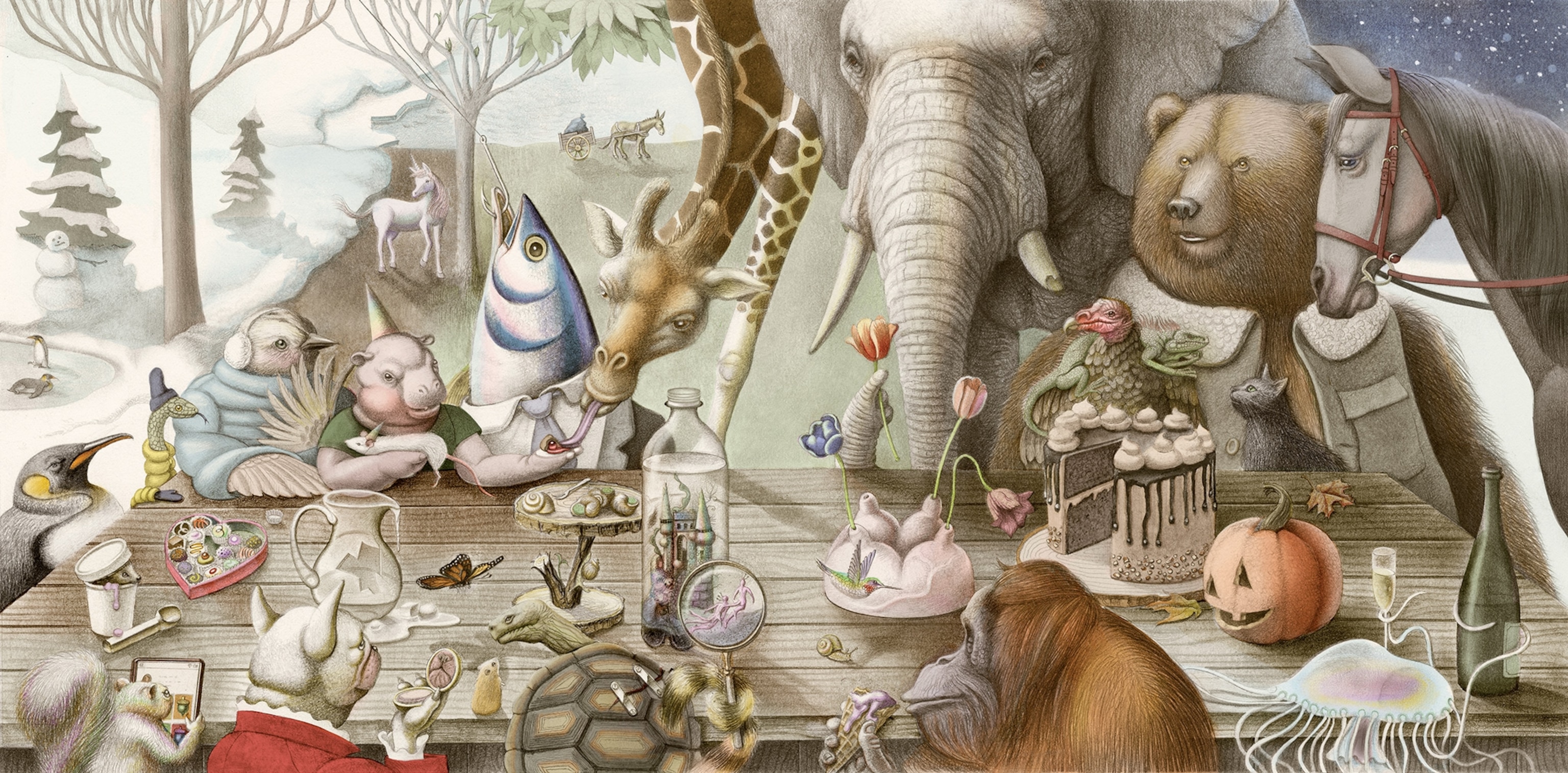

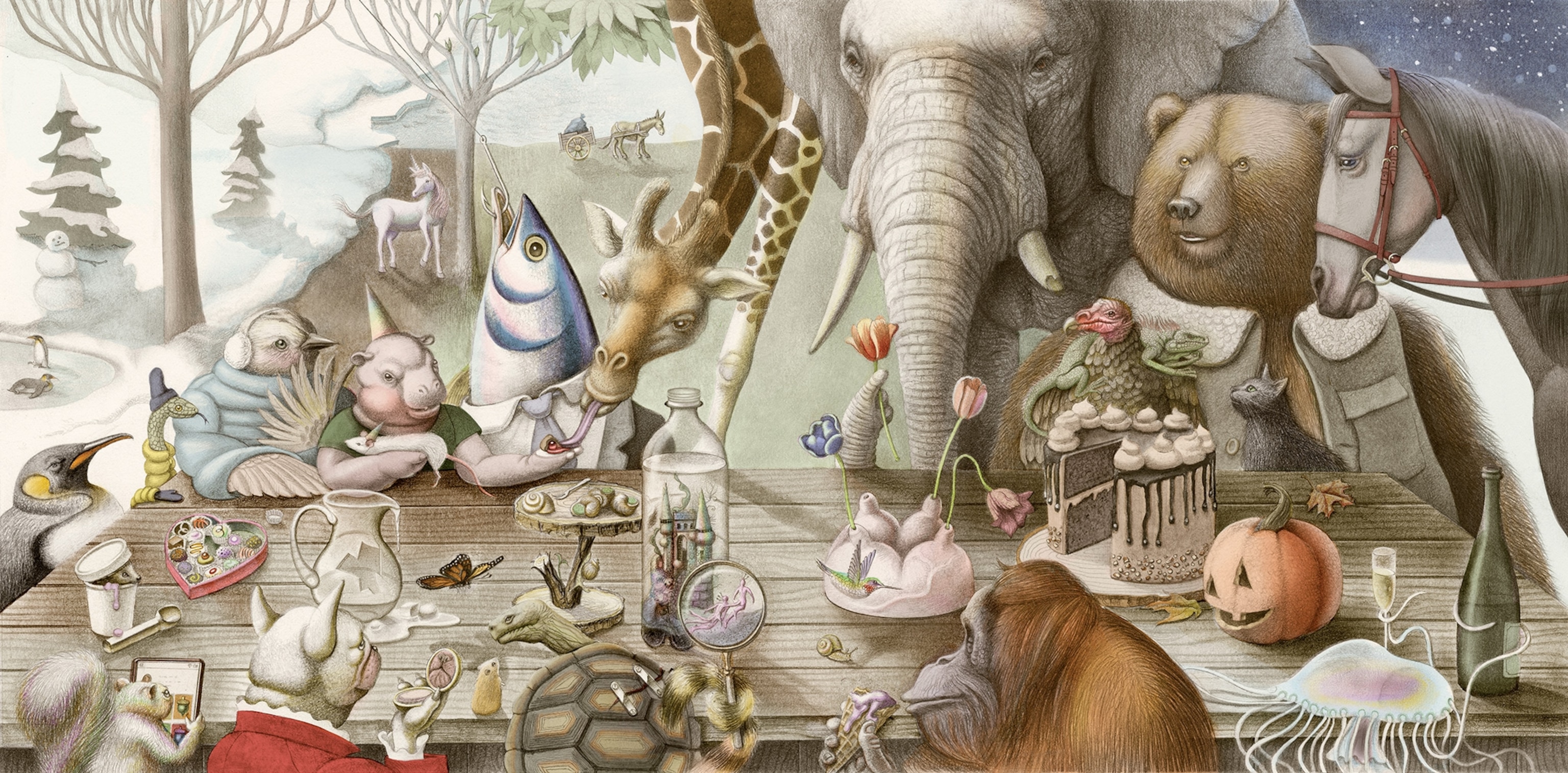

Go to any of the dozens of holiday calendars that have sprung up online. Pick a random day, week, or month, and you’ll find an almost disturbing number of observances dedicated to a wide breadth of subjects. Days referencing animals specifically are plentiful, even crowded. In 2020, Fat Bear voting opened a week after the observances of World Rhino Day and Elephant Appreciation Day (September 22). And the winning bear—747, an absolute monster whose belly nearly touched the ground—was crowned on October 6, also known as Badger Day.

The observances’ intents are a mixture: altruistic, commercial, historical, fantastical, serious, funny. Some involve physical events (like sunset “batwalks” to mark Bat Week, October 24-31). Others exist primarily as hashtags or posts on social media—but the line between a strictly online presence and a more “legitimate” existence is thin, often to the point of disappearance. According to a May 16 calendar entry, National Sea Monkey Day exists to celebrate “the tiny brine shrimp that swim around mail-order aquariums”—and from little more than that, the holiday not only went viral; it was written up in Newsweek.

Getting attention is one point, if not the point, of animal holidays. Groups name days to advocate for conservation, shine a light on animal cruelty, and educate people about biodiversity. Think World Elephant Day (August 12), World Hippo Day (February 15), World Giraffe Day (June 21), International Orangutan Day (August 19), to name just a few. The United Nations designates more than 170 special weeks and days, including World Bee Day on May 20 (birthday of beekeeping pioneer Anton Janša) and World Tuna Day on May 2, to spotlight both tuna’s role in feeding the world and the importance of not overfishing it.

Other holidays seek to rehab the reputations of maligned creatures. World Rat Day (April 4) was started in 2002 by pet-rat enthusiasts. They endorse rats’ good qualities—clean, sociable, intelligent—and decry “unthinking prejudice” against the rodents (let’s move on from the bubonic plague). Also dedicated to image makeovers: Iguana Awareness Day (September 8) and International Vulture Awareness Day (first Saturday in September).

Two days urge ophidiophobics to master their fear of a certain slithering form: National Serpent Day on February 1 and World Snake Day on July 16 (though how the animals or holidays differ from each other isn’t entirely clear). Conversely, the American Tortoise Rescue organization sponsors World Turtle Day (May 23) and—even though turtles and tortoises are not the same—dedicates the day to both.

Of course the difference between International Land Snail Day (November 7) and National Escargot Day (May 24) needn’t be explained. Note that you have six months to repent for celebrating the latter before the former comes around.

On August 20, feel free to squash the honoree. It’s World Mosquito Day, to mark the 1897 discovery that female mosquitoes transmit malaria to humans.

There’s commercial value to the buzz that these holidays generate, as some businesses have noticed. Consider Cow Appreciation Day, which sounds like an homage to those beloved bovines. In fact, it’s a promotion on the second Tuesday of July by fast-food restaurant Chick-fil-A, which gives free chicken to customers who dress up in cow-patterned clothes. Yet how an observance pays off isn’t always black and white. Sponsoring National Make A Dog’s Day (October 22) likely helps carmaker Subaru’s reputation—but in 2020, it also helped find homes for more than 20,000 shelter pets.

October is Adopt-a-Dog Month, March 2 is International Rescue Cat Day—and between them, canines and felines have inspired scores of observances.

National Answer Your Cat’s Questions Day (January 22) urges humans to try to see the world through cats’ eyes, the better to answer questions such as: Why won’t you let me on the kitchen counter? It might also make us more appreciative of Hairball Awareness Day, observed on the last Friday in April. And there are many more cat holidays, including Happy Mew Year Day for Cats (January 2), Hug Your Cat Day (June 4), Ginger Cat Appreciation Day (September 1)—and at least three days in tribute to black cats.

Not to be outdone, canines have Lost Dog Awareness Day (April 23), National Black Dog Day (October 1), National Sled Dog Day (February 2), Bulldogs Are Beautiful Day (April 21)—and on and on. For the cat and dog lovers: March 3 is What if Cats and Dogs Had Opposable Thumbs Day.

Animal observances aren’t purely for advertisement or philanthropy, fun or seriousness. They reflect the complex ways we humans interact with nature and each other. Take Monkey Day, December 14, which two art students created in 2000 as a lark. As the observance spread through the pair’s art and comics, though, it started drawing attention to declining monkey populations. More than two decades out, the holiday has been recognized on Jane Goodall’s Facebook page and on nationalgeographic.com, and primate conservation has become a central message.

Which brings us back to Fat Bear Week. Mike Fitz, now a resident naturalist and author of a book on the bears, never expected the holiday to get this big. He uses it to bring attention to the salmon runs where the bears get so fat, and to how climate change threatens the ecosystem. During Fat Bear Week 2020, bear cam views on websites including fatbearweek.org topped 2.5 million—and, between donations and matches, a park conservancy fundraiser took in more than $200,000.

It’s a nifty shift from funny clickbait to serious conservation education, but Fitz feels comfortable straddling this line. Two hundred grand from fat bears is something to celebrate.

Oliver Whang is a freelance journalist working for National Geographic, the New Yorker, and the New York Times; he studies philosophy at Princeton University.

This story appears in the August 2021 issue of National Geographic magazine.