Sami

The People Who Walk With Reindeer

Two hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle, near the jagged tips of Norway's crown, the sun does not set for weeks on end during the summer months, and the midnight sun bounces off fields of midsummer snow. The solstice comes and goes, but the Sami reindeer herders are too busy to pay much attention. "We're always in the middle of calf marking at this time," Ingrid Gaup says, referring to the yearly ritual in which the herding families carve their ancient marks into the ears of the new calves. In the Sami's homeland, spread across northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia, the notion of time is untethered from the cycles of the sun and is yoked instead to something far more important: the movement of the reindeer.

Sami herders call their work boazovázzi, which translates as "reindeer walker," and that's exactly what herders once did, following the fast-paced animals on foot or wooden skis as they sought out the best grazing grounds over hundreds of miles of terrain. Times have changed. Herders are now assigned to specific parcels of the reindeer's traditional grazing territories at designated times of the year. To make the lifestyle tenable, herders need expensive all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) and snowmobiles to maintain hundreds of miles of fences between territories and move large herds in accordance with land-use regulations—even when they clash with the instincts of the reindeer. As Ingrid's husband, Nils Peder Gaup, explains, "Reindeer think with the nose, not the eyes. They go with the wind."

Like many Sami of his generation, Nils Peder went to a compulsory boarding school where his native tongue was forbidden as part of the country's "Norwegianization" policies. Sami have been given more autonomy since then, but irretrievable damage was done to their language, now spoken by a minority. The Gaups are among the few Sami—a population estimated at around 70,000—who still herd reindeer.

Each June, after a long journey into the mountainous tundra of northern Norway, the Gaup family waits for the herd in tepee-like structures called lávut. They will spend sleepless nights marking the calves before moving the reindeer to their summer grazing grounds in the fjords.

At the first hint of the herd's arrival, the dogs in the encampment leap to their feet, ears erect. The herd spills over a far ridge, swelling like a stream down the mountainside. Other herders crest the rise on their ATVs, driving hundreds of thundering reindeer into a makeshift stockade. Small children, stiff as starfish in their snowsuits, toddle blithely inside the corral, unfazed by the reindeer stampede around them.

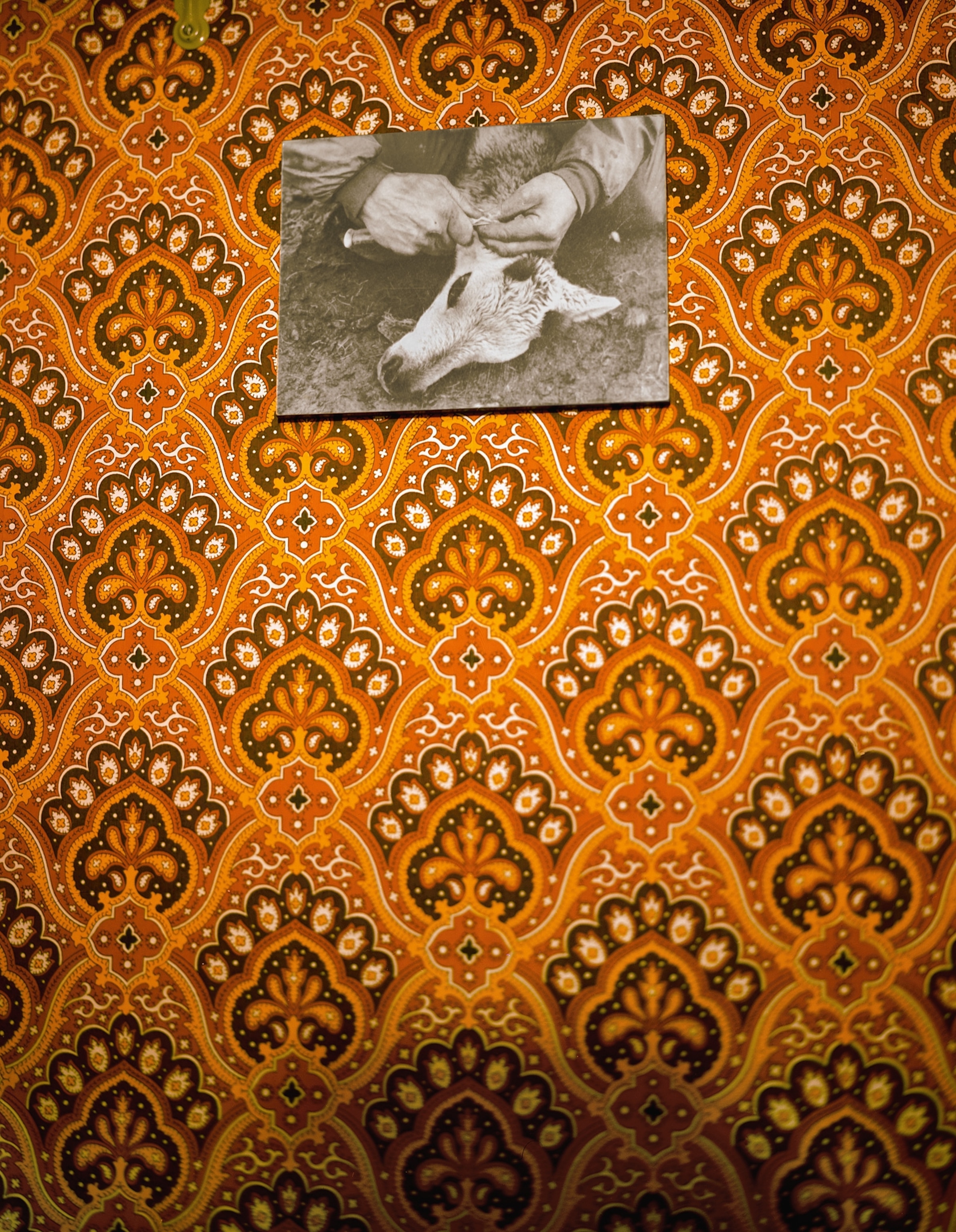

"I teach reindeer work to all of my children," says Nils Peder, as he guides his youngest son in marking a calf. His older children are so adept with sharp knives that they return calves to the mothers with only the faintest traces of blood on their ears. "Children must lift the culture," Nils Peder says, though he acknowledges the pressures of outside cultural influences. Herding families now live in modern homes equipped with Internet and television. Sara, the youngest of the Gaups' five children, spends much of the calf marking texting friends on her cell phone.

As herders face greater challenges, what path will girls like her choose? If reindeer herding disappears, Sami traditions may vanish too. The language itself reflects this powerful bond: The word for "herd" is eallu; the word for "life" is eallin.