The Forgotten Road

Chinese tea and Tibetan horses were long traded on a legendary trail. Today remnants of the passageway reveal grand vistas—and a surprising new commerce.

Deep in the mountains of western Sichuan I'm hacking through a bamboo jungle, trying to find a legendary trail. Just 60 years ago, when much of Asia still moved by foot or hoof, the Tea Horse Road was a thoroughfare of commerce, the main link between China and Tibet. But my search could be in vain. A few days earlier I met a man who used to carry backbreaking loads of tea along the path; he warned me that time, weather, and invasive plants may have wiped out the Tea Horse Road.

Then, with one wide sweep of my ax, the bamboo falls. Before me is a four-foot-wide cobblestone trail curving up through the forest, slick with green moss, almost overgrown. Some of the stones are pitted with water-filled divots, left by the metal-spiked crutches used by hundreds of thousands of porters who trod this trail for a millennium.

The vestigial cobblestone path lasts only 50 feet, climbs a set of broken stairs, then once again disappears, swept away by years of monsoonal deluges. I carry on, entering a narrow passage where the sidewalls are so steep and slippery I have to hang on to trees to keep from falling into the bouldery creek far below. I'm hoping, at some point, to cross over Maan Shan, a high pass between Yaan and Kangding.

That night I camp high above the creek, but the wood is too wet to make a fire. Rain pounds the tent. In the morning I probe ahead another 500 yards before an impenetrable wall of jungle stops me, for good. I'm forced to admit that here at least the Tea Horse Road has vanished.

In fact, most of the original Tea Horse Road is gone. Recklessly rushing to modernity, China has been paving over its past as fast as possible. Before the trail is bulldozed or obliterated, I've come to explore what's left of this once famous but now all-but-forgotten route.

The ancient passageway once stretched almost 1,400 miles across the chest of Cathay, from Yaan, in the tea-growing region of Sichuan Province, to Lhasa, the almost 12,000-foot-high capital of Tibet. One of the highest, harshest trails in Asia, it marched up out of China's verdant valleys, traversed the wind-stripped, snow-scoured Tibetan Plateau, forded the freezing Yangtze, Mekong, and Salween Rivers, sliced into the mysterious Nyainqentanglha Mountains, ascended four deadly 17,000-foot passes, and finally dropped into the holy Tibetan city.

Snowstorms often buried the western part of the trail, and torrential rains ravaged the eastern portion. Bandits were a constant threat. Yet the trail was heavily used for centuries, even though the cultures at either end at times despised each other (and still do). The desire to trade was why the trail existed, not the romantic swapping of ideas and ethics, culture and creativity associated with the legendary Silk Road to the north. China had something Tibet wanted: tea. Tibet had something China desperately needed: horses.

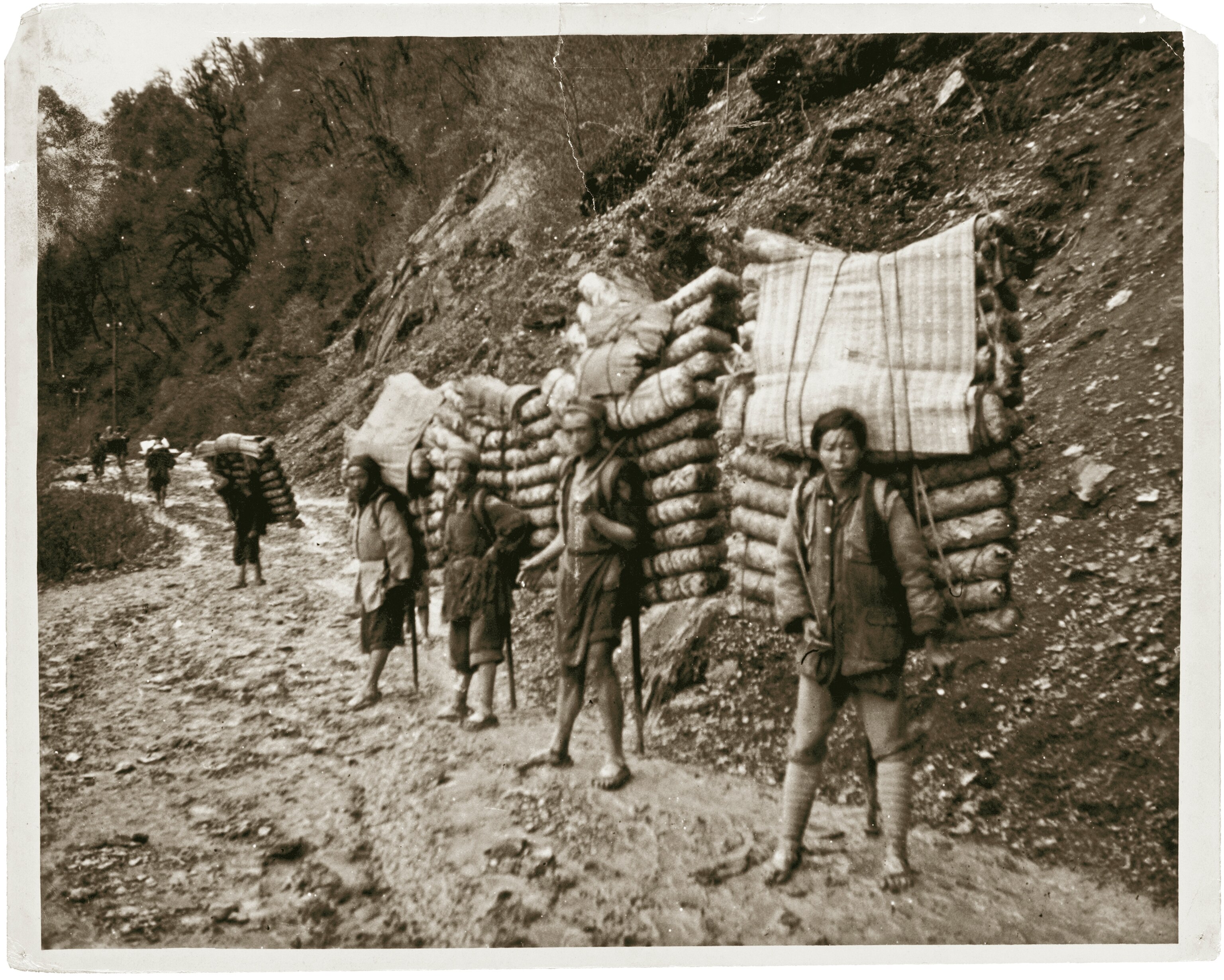

Today the trail lives on in the memories of men like Luo Yong Fu, a watery-eyed 92-year-old whom I met in the village of Changheba, a ten-day walk for a tea porter west of Yaan. When I first arrived in Sichuan, I was told no tea porters were still alive. But as I walked the last remnants of the Chamagudao, the Chinese name for the ancient trade route, I met not only Luo, but also five others, all eager to share their stories. Stooped but still surprisingly strong, Luo Yong Fu wore a black beret and a blue Mao jacket with a pipe in the pocket. He had worked on the Tea Horse Road as a porter, carrying tea to Tibet from 1935 to 1949. Luo's load of tea always weighed 135 pounds or more. At the time, he weighed less than 113 pounds.

"Difficulties were so great and the hardship so enormous," Luo said. "It was a terrible job."

Luo had crossed back and forth over Maan Shan, the point I had hoped to reach. In winter the snow was three feet deep and six-foot icicles hung from the rocks. He said the last time someone had crossed the pass was in 1966, so he doubted whether I would be able to do it.

But I did get a glimmer of what it must have been like to travel the road. In Xinkaitian, the first stop on the tea porters' 20-day trek from Yaan to Kangding, clean-shaven Gan Shao Yu, 87, and bristle-faced Li Wen Liang, 78, insisted on acting out their lives as porters.

Backs bent beneath immense, imaginary loads of brick tea, veiny hands on T-shaped crutches, heads down and eyes on their splayed feet, the two old men showed me how they wobbled single file along a wet stretch of cobblestone. After seven steps Gan stopped and stamped his crutch three times, following tradition. Both men circled their crutches around to their backs to rest their wood-frame packs atop the crutch. Wiping sweat from their brows with phantom bamboo whisks, they croaked out the tea porter song:

Seven steps up, you have to rest.

Eight steps down, you have to rest.

Eleven steps flat, you have to rest.

You are stupid, if you don't rest.

Tea porters, both men and women, regularly carried loads weighing 150 to 200 pounds; the strongest men could carry 300. The more you carried, the more you were paid: Every pound of tea was worth a pound of rice when you got back home. Wearing rags and straw sandals, porters used crude iron crampons for the snowy passes. Their only food was a satchel of corn bread and an occasional bowl of bean curd.

"Of course some of us died on the way," Gan said solemnly, his eyelids half shut. "If you got caught in a snowstorm, you died. If you fell off the trail, you died."

Tea portering ended soon after Mao took over the country in 1949 and a highway was built. Redistributing land from the wealthy to the poor, Mao released the tea porters from servitude. "It was the happiest day of my life," Luo said. After he received his parcel of land, he began to grow his own rice and "that sad period passed away."

Tea was first brought to Tibet, legend has it, when Tang dynasty Princess Wen Cheng married Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo in A.D. 641. Tibetan royalty and nomads alike took to tea for good reasons. It was a hot beverage in a cold climate where the only other options were snowmelt, yak or goat milk, barley milk, or chang (barley beer). A cup of yak butter tea—with its distinctive salty, slightly oily, sharp taste—provided a mini-meal for herders warming themselves over yak dung fires in a windswept hinterland.

The tea that traveled to Tibet along the Tea Horse Road was the crudest form of the beverage. Tea is made from Camellia sinensis, a subtropical evergreen shrub. But while green tea is made from unoxidized buds and leaves, brick tea bound for Tibet, to this day, is made from the plant's large tough leaves, twigs, and stems. It is the most bitter and least smooth of all teas. After several cycles of steaming and drying, the tea is mixed with gluey rice water, pressed into molds, and dried. Bricks of black tea weigh from one to six pounds and are still sold throughout modern Tibet.

By the 11th century, brick tea had become the coin of the realm. The Song dynasty used it to buy sturdy steeds from Tibet to take into battle against fierce nomadic tribes from the north, antecedents of Genghis Khan's hordes. It became the prime trading commodity between China and Tibet.

For 130 pounds of brick tea, the Chinese would get a single horse. That was the rate set by the Sichuan Tea and Horse Agency, established in 1074. Porters carried tea from factories and plantations around Yaan up to Kangding, elevation 8,400 feet. There tea was sewn into waterproof yak-skin cases and loaded onto mule and yak trains for a three-month journey to Lhasa.

By the 13th century China was trading millions of pounds of tea for some 25,000 horses a year. But even all the king's horses couldn't save the Song dynasty, which fell to Genghis's grandson, Kublai Khan, in 1279.

Nonetheless, bartering tea for horses continued through the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) and into the middle of the Qing dynasty (1645-1912). When China's need for horses began to wane in the 18th century, tea was traded for other goods: hides from the high plains, wool, gold, and silver, and, most important, traditional Chinese medicinals that thrived only in Tibet. These are the commodities that the last of the tea porters, like Luo, Gan, and Li, carried back from Kangding after dropping off their loads of brick tea.

Just as China's imperial government used to regulate the tea trade in Sichuan, so monasteries influenced the trade in theocratic Tibet. The Tea Horse Road, known to Tibetans as the Gyalam, connected the important monasteries. Over the centuries, power struggles in Tibet and China changed the Gyalam's route. There were three main trunk lines: one from the south in Yunnan, home of Puer tea; one from the north; and one from the east cutting through the middle of Tibet. Because it was the shortest, this center route handled most of the tea.

Today the northern route, Highway 317, is blacktop. Near Lhasa it parallels the Qinghai-Tibet railway, highest in the world. The southern route, Highway 318, is also oiled. These highways are major arteries of commerce, clogged with trucks carrying every imaginable commodity from tea to school tablets, solar panels to plastic plates, computers to cell phones. Almost all of it goes one way—west to Tibet, to meet the needs of a ballooning Chinese population.

The western half of the middle route has never been paved. This is the segment that winds through Tibet's remote Nyainqentanglha Mountains, an area so rugged and inhospitable it was simply abandoned decades ago and the entire area closed to travelers.

I'd seen what was left of the original trail in China. To do the same in Tibet, I'd have to find a way into these forbidden mountains. I called my wife, Sue Ibarra, who is an experienced mountaineer, and asked her to meet me in Lhasa in August.

We begin our journey at the Drepung monastery, which lies at the western end of the Tea Horse Road—less than a day's horse ride from Lhasa. Built in 1416, it has a cavernous tea kitchen, or gyakhang. Seven iron cauldrons from six to ten feet in diameter are imbedded in a gargantuan, wood-fired, stone hearth.

Standing above a cauldron, Phuntsok Drakpa cleaves off tome-size slabs of yak butter into the steaming tea. "There were once 7,700 monks here who drank tea twice a day," he says. "More than a hundred monks worked in this tea kitchen." Swathed in a sleeveless maroon robe, Drakpa has been the tea master in the monastery for 14 years. "To Tibetan monks," he says, "tea is life."

Today only 400 monks reside in the monastery, and only two small cauldrons are in use. "For one little cauldron, 25 bricks of tea, 70 kilos of yak butter, 3 kilos of salt," says Drakpa, stirring this recipe for 200 with a wooden spoon tall as a human. "For the biggest cauldron, we used seven times that much."

From the monastery, Sue and I set out for the city of Nagqu, a five-hour drive north from Lhasa, to attend the annual horse festival. We want to see the legendary horses that gave their name to the Tea Horse Road. The weeklong event used to be held on the open plains, but ten years ago a concrete stadium was built so Chinese officials would have someplace to sit. When we arrive the next morning, Tibetans pack the stands: women with high cheekbones, high heels, and long braids heavy with silver and amber; men in felt cowboy hats and the long-sleeved coats they call chubas; sockless kids in cheap sneakers. Hawkers sell spicy boiled potatoes and cans of Budweiser. Blaring speakers announce each event in Tibetan and Chinese. It's a rodeo atmosphere, except for the Chinese policemen stationed every ten yards along the bleachers, marching in squadrons around the field, and lurking in plainclothes.

Down on the field, horse and rider seem to defy gravity. A contestant gallops almost out of control, dangling like an acrobat off the side to pluck a white silk scarf from the ground. Clods of mud propel into the sharp blue sky. Holding the scarf aloft, the Tibetan cowboy wheels his rearing horse to the roar of the crowd.

The Nagqu Horse Festival is one of the few surviving events celebrating Tibet's equestrian heritage. Through centuries of selective breeding, Tibetans created a premium horse called the Nangchen. Standing only 13.5 hands high (about 4.5 feet—smaller than most American breeds), fine-limbed and handsome-faced, with enlarged lungs adapted to life on the 15,000-foot-high, oxygen-starved Tibetan Plateau, Nangchen steeds were bred to be inexhaustible and sure-footed on snowy passes. These were the horses coveted by the Chinese centuries ago.

Today Nagqu sits on modern Highway 317, the northern branch of the Tea Horse Road. All signs of the former trade route have vanished, but just a day's drive southeast, temptingly close, are the Nyainqentanglha Mountains, where the original trail once passed. I am captivated by the possibility that back in the deep valleys Tibetans might still ride their indefatigable horses along the original trail. Perhaps, hidden in the vast hinterland, there is even still trade along the road. Then again, maybe the trail has vanished as it did in Sichuan, wiped out by howling wind and tumbling snow.

One rainy black morning halfway through the festival, while the police are looking the other way, Sue and I slip off in a Land Cruiser to find out what has happened to Tibet's Tea Horse Road. We race all day on dirt roads, grinding over passes, almost rolling on steep slopes. We don't stop at checkpoints, and we creep right past village police stations. By nightfall we reach Lharigo, a village between two enormous passes that once served as a sanctuary along the Gyalam. Surreptitiously, we go door-to-door looking for horses to take us up to 17,756-foot Nubgang Pass. There are none to be found, and we're directed to a saloon on the edge of town. Inside, Tibetan cowboys are drinking beer, shooting pool, and placing bets on a dice game called sho. They laugh when we ask for horses. No one rides horses anymore.

Outside the saloon, instead of steeds of muscle standing in the mud, there are steeds of steel: tough little Chinese motorcycles decorated like their bone-and-blood predecessors—red-and-blue Tibetan wool rugs cover the saddles, tassels dangle from the handlebars. For a price, two cowboys offer to take us to the base of the pass; from there we must walk.

We set off in the dark the next morning, backpacks strapped to the bikes like saddlebags. The cowboys are as adept on motorbikes as their ancestors were on horseback. We bounce through black bogs where the mud is two feet deep, splash through blue braided streams where our mufflers burble in the water.

Up the valley we pass the black tents of Tibetan nomads. Parked in front of many of the yak hair tents are big Chinese trucks or Land Cruisers. Where did nomads get the money to buy such vehicles? Certainly not from the traditional yak meat-and-butter economy.

It takes five hours to cover the 18 miles to Tsachuka, a nomad camp at the base of the Nubgang Pass. The ride thoroughly jars our spines. The cowboys build a small sagebrush campfire and, after a lunch of yak jerky and yak butter tea, Sue and I set off on foot for the legendary pass.

To our delight, the ancient path is quite visible, like a rocky trail in the Alps, winding up meadows speckled with black, long-horned yaks. After two hours of hard uphill hiking, we pass two shimmering sapphire tarns. Beyond these lakes, all green disappears and everything turns to stone and sky. Mule trains of tea stopped crossing this pass over a half century ago, but the trail had been maintained for a thousand years, boulders moved and stone steps built, and it's all still here. Sue and I zigzag through the talus, along the walled path, right up to the pass.

The saddle-shaped Nubgang Pass has clearly been abandoned. The few prayer flags still flapping are worn thin, the bones atop the cairns bleached white. There is a silence that only absence can create. Sue stares at the snowcapped peaks surrounding us, raw gray pyramids. Over centuries, only a few Westerners have ever stood here. I catch Sue's eyes following the enduring trail down into the next valley.

"Can you see it?" she asks.

I can. In my imagination I see a mule train of a hundred animals plodding up toward us, dust swirling around their hooves, loads of tea rocking side to side, the cowboys alert for bandits waiting in ambush on the Nubgang Pass.

Our motocowboys are waiting for us the next morning when we return from the pass. We saddle up and begin the long ride out, bumping and bashing down glacial valleys.

At midday we stop at two black nomad tents, surrounded by neat stacks of yak dung. A large solar panel hangs on each tent, and parked in the grass are a truck, a Land Cruiser, and two motorcycles. The nomads invite us in and offer cups of scalding yak butter tea.

Inside the tent, an old woman is twirling a prayer wheel and mumbling mantras, a young man is cooking in a shaft of light, and a few middle-aged men are sitting on thick Tibetan rugs. Through sign language and a pocket dictionary, I ask the men how they can afford their vehicles. They grin wildly, but the conversation strays. After we've finished heaping bowls of rice with greens and hunks of yak meat, the head of the household pulls out a blue metal box, unlocks it, pries open the lid, and motions for us to have a look.

Inside are hundreds of dead caterpillars.

"Yartsa gompo," our host says proudly. Each dried caterpillar, he explains, will sell for between four and ten dollars. There's probably ten grand in dead caterpillars in his padlocked blue box. Yartsa gompo—called chong cao in China—is a parasite-infected caterpillar that lives only in grasslands above 10,000 feet. The parasite, a kind of fungus, kills the caterpillar, then feeds on its body.

Every spring Tibetan nomads wander their yak meadows with a small, curved metal trowel looking for the caterpillars. Poking up less than an inch, the purplish, toothpick-shaped yartsa gompo stem is extremely difficult to spot—but the caterpillars are worth more than all their yaks combined.

In Chinese medicine shops throughout Asia, chong cao is sold as a cure-all for the ravages of aging, for health issues ranging from infection to inflammation, fatigue to phlegm to cancer. Displayed in climate-controlled glass cases, the highest quality caterpillars sell for nearly $80 a gram, which is about twice the price of today's gold. The Tibetan closes his treasure box and tucks it into the side of his tent. Before we depart, he insists we have one more cup of burning yak butter tea.

As we ride off across the high plains, I am struck by the irony of this new commerce along the old Tea Horse Road. Tibetans no longer ride horses, and tea is no longer the primary drink in urban Tibet (Red Bull and Budweiser are everywhere). And yet, just as tea still comes from traditional regions of China, chong cao can be found only on the Tibetan Plateau. Shoes and shampoos, TVs and toasters may be pouring westward along the paved portions of the ancient trade route, but something is going back east. Today the Chinese are willing to pay as dearly for magic caterpillars as they once did for invincible horses.