The hidden world of whale culture

From singing competitions to food preferences, scientists are learning whales have cultural differences once thought to be unique to humans.

Tune into Secrets of the Whales, a Disney+ original series from National Geographic that premieres Earth Day, April 22, 2021.

Hear more about the secret culture of killer whales in our podcast, Overheard at National Geographic.

John Ford wanted a whale’s-eye view. One summer day in 1978 a pod of killer whales raced toward a pebbled beach on British Columbia’s Vancouver Island. The young biologist was waiting in a wet suit and snorkel. The ghostly black-and-white procession steamed in like a team of U-boats, low and fast. Ford pressed on his face mask and slipped into the sea. In waters barely 10 feet deep, the creatures slowed and rolled to their sides. Bodies partially submerged, the fans at the end of their tails—their flukes—wagging, the whales began to twist and shimmy. One by one, each scuffed its side and belly on the stones, like grizzlies scratching against the pines.

Ford, age 66, has now studied killer whales, the largest dolphin and from the branch of the Cetacean order known as toothed whales, for more than 40 years. He’s seen this phenomenon, called beach rubbing, countless times since that first underwater glimpse. He can’t say for certain why the animals do it. He suspects it’s a form of social bonding. A larger question, though, has gnawed at him for much of his career: How come these killer whales, or orcas, do it, but not their nearly identical neighbors just to the south?

Beach rubbing is routine among this population, called northern residents because they ply inland seas during summer and fall between the Canadian mainland and Vancouver Island. Not so their neighbors to the south. The orcas around the border with Washington State, where I live, have never been documented performing this ritual.

Washington’s killer whales, called the southern residents, instead have their own conventions. They hold “greeting ceremonies,” facing off in tight lines before exploding in underwater parties of rubs and calls. That’s exceedingly rare up north. Southern residents are aerialists, performing twisting leaps and belly flops. Northern residents breach far less. Some years the southern residents push dead salmon around with their heads. Not the northerners: They occasionally headbutt one another, bumping noggins like bighorn sheep. “They just swim at each other and sort of collide,” Ford says.

The two populations don’t even converse with the same vocabulary. Northern residents emit elongated, shrill, metallic squeals that sound like air escaping balloons. Southern residents add monkey hoots and goose honks. To Ford’s practiced ear, the pitches and intonations sound as different as Mandarin and Swahili.

Yet in every other meaningful way, the northern and southern residents are indistinguishable. For months at a time, they occupy adjacent seas. Their ranges overlap. Although many varieties of killer whales exist around the world, the northern and southern whales share almost identical genetics. From the northern Pacific to the seas around Antarctica, killer whales also have varying diets. Some eat sharks, porpoises, penguins, or manta rays. In Patagonia, they launch onto rocky shores and pluck seal pups off the beach. In Antarctica, killer whales flush Weddell seals off floating ice, teaming up to swamp floes and wash dinner into the drink. But the northern and southern residents are both pescatarians, and eat mostly just one species: Chinook salmon.

How could two groups from essentially the same place be genetically similar and yet speak and act so differently? For years, Ford and a few colleagues would only whisper what this paradox implied. Is it possible that these complex social beings weren’t driven solely by the inherited twitch of genetic instinct? Were killer whales passing on unique traits influenced by more than their environment or DNA? Could whales have their own cultures?

(Listen to a humpback whale song, and explore what it looks like as sheet music.)

The very notion seemed blasphemous. Anthropologists long had considered culture—the ability to socially accumulate and transfer knowledge—strictly a human affair. But researchers had described how songbirds learn dialects and transmit them across generations, and Ford proposed that killer whale groups might do the same. Then he started hearing about the findings of biologists studying a creature a world away: the sperm whale. Those scientists had been building a case that some whale species act and communicate differently based on how they’re raised. It appeared these cetaceans might carry on diverse traditions, just as some humans eat with chopsticks while others use forks.

Today many scientists believe some whales and dolphins, like humans, have distinct cultures. Researchers see signs in sperm whales in the Galápagos and the Caribbean, in humpbacks across the South Pacific, in Arctic belugas, and in the Pacific Northwest’s killer whales. The possibility is prompting new thinking about how some marine species evolve. Cultural traditions may help drive genetic shifts, altering what it means to be a whale. But this idea is also reshaping our view of what separates us from these aquatic beasts. Whale culture, it seems, is rattling timeworn conceptions of ourselves.

Humans are a narcissistic breed. Throughout history we’ve vacillated between seeing animals through the lens of our own behavior and refusing to accept that we’re anything alike. This is particularly true of whales. They’re often viewed as almost human or not like us at all. We anthropomorphize or insist on our own uniqueness. Neither, of course, is entirely correct.

Whales reside in a foreign place we’re just coming to understand. It’s hard to imagine a home less like ours. The deep ocean is a universe we’ve seen less of than the surface of the moon. There are mountains and rivers but few borders. Life traverses a vertical plane. It’s so dark that sight is of limited value. Entire relationships are forged through sound.

And yet, as we spend billions scanning the heavens for alien life, the mysteries we’re unraveling beneath the waves reveal foreigners here at home that are more like us than we knew. Whales’ alliances, the intricacies of their conversations, and the ways they care for their young seem eerily familiar.

Some may even openly mourn. In 2018 a southern-resident killer whale known as Tahlequah pushed the carcass of her newborn, which had died shortly after its birth, around with her snout for 17 days. “For years scientists vigorously avoided using emotional terms like happy, sad, playful or angry when describing animal behavior,” writes Joe Gaydos, who oversees a university program in Washington State to protect marine life through science and education. But Gaydos and many whale biologists believe Tahlequah’s behavior was a show of grief.

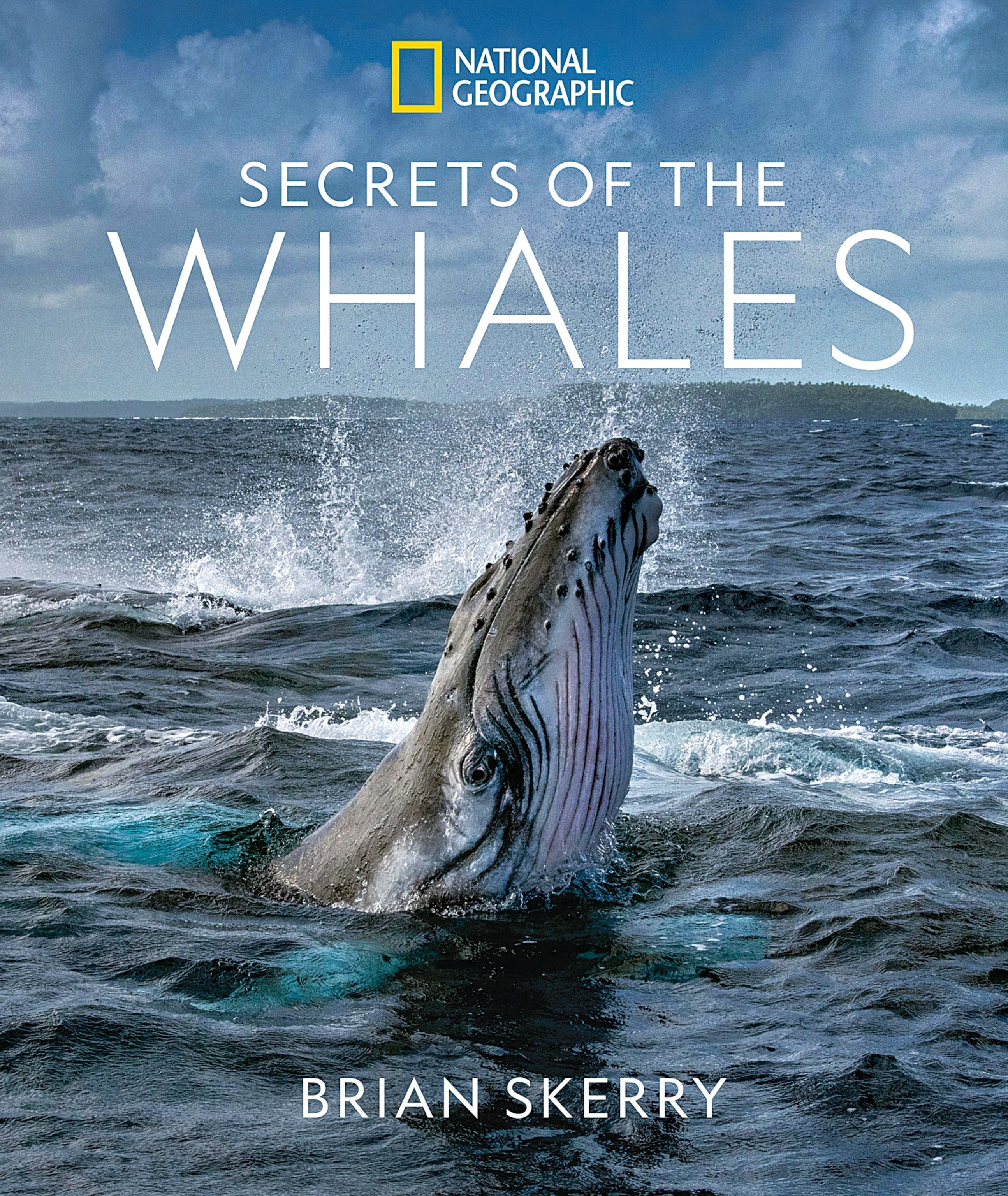

When photographer Brian Skerry first mentioned his interest in exploring the culture of these remarkable animals, one group leaped to mind. I live four miles from Puget Sound, where three pods of southern-resident killer whales spend a portion of their year zipping about in tight formations like squadrons of Air Force Thunderbirds. When their dorsal fins break the surface near shore, crowds gather with cameras, hoping to catch a memorable hop or acrobatic lunge. What secrets might these whales carry? Could knowing them help us live better together?

Scientists have long understood that many whale actions must be picked up from peers or elders. It’s learned behavior and hardly shocking. Even Aristotle knew animals learned from one another. Songbirds raised away from their own families “utter a different voice from their parents,” he wrote. Charles Darwin noted that animal traps eventually must be moved because wild creatures “imitate each other’s caution.”

While genes determine the shape and function of a creature’s body, encoding instructions for essential traits and behaviors, social learning is received wisdom, the development of neural connections that let animals learn from the knowledge of those around them. Scientists generally agree that culture requires that behaviors be socially learned and shared widely, and that they persist. As groups of animals transmit multiple learned behaviors, they can develop sets of habits wholly distinct from others of their species. For example, the ability to throw is genetic. But throwing a curveball requires social learning, and playing baseball instead of cricket is culture.

The danger, though, is to confuse culture with intelligence. Scientists don’t all agree on whether intelligence is an essential ingredient for culture. Social learning cuts widely across the animal kingdom, and not just among beings we consider “smart”—whales, primates, crows, elephants. Bumblebees may choose flowers based on the behavior of experienced bees. Mongooses learn from siblings and cousins to break open eggs or smash beetles.

But being smart clearly helps. And cetaceans’ capacity for learning captured our imaginations early. For decades we’ve packed marine theme parks, applauding killer whales, belugas, or bottlenose dolphins that sing or vault through hoops in giant pools. These feeble attempts to corral their skills barely scratch the surface of their talents. In 1972 a scientist studying a bottlenose dolphin calf named Dolly exhaled cigarette smoke onto the window of her enclosure during a break. “The observer was astonished when the animal immediately swam off to its mother, returned and released a mouthful of milk which engulfed her head, giving much the same effect as had the cigarette smoke,” researchers wrote at the time.

Among some whales, intelligence may even be an evolutionary response to culture, as social animals spread learned wisdom far and wide. For culture to exist, individuals must come up with new ways of doing things that get shared among peers. And whales can be shrewd innovators. A few hungry sperm whales off Alaska in the late 1990s found new ways to snack: They stripped black cod off commercial fishing boat longlines. Using underwater cameras, scientists recorded a whale delicately grabbing a line with its massive jaw, creating tension, and then sliding its mouth up the strand until the vibrations popped off a fish. The practice, previously rare, quickly spread. In the Gulf of Maine, in 1980, one humpback was seen hunting in a new way. Before blowing bubbles around schools of sand lances to disorient them, the whale smacked the surface with its fluke. Humpbacks regularly use the bubble technique, but the fluke slap was new. It’s not clear how it helps, but by 2013, scientists counted at least 278 whales that hunted this way.

Whales’ alliances, their intricate conversations, and how they attract mates or care for their young seem eerily familiar. The mysteries we’re unraveling beneath the waves reveal creatures a lot like us.

For years scientists thought animals were incapable of broad, sustained, intergenerational sharing. That notion began changing in 1953. That year, a young macaque, Imo, was spotted on Koshima island, Japan, washing a sweet potato in a stream. Before then, the island’s macaques simply wiped dirt off their food. Soon, scientists documented macaques by the dozens washing them instead. Long after Imo died, macaques still carted potatoes to shore to dunk them in the sea.

Then, in 1999, Andrew Whiten, a cognitive scientist with Scotland’s University of St. Andrews, published a landmark paper with primate experts, including Jane Goodall. They noted that dozens of chimpanzee traditions—grooming, rain dancing (strutting about at the first signs of precipitation), cracking nuts with hammers, poking termite mounds with sticks—appeared across some chimp communities but not others. “If you watch a chimpanzee long enough and check out these behaviors, you can pretty much tell where that chimp came from,” Whiten tells me. And watching people behave is often how we identify human culture.

Not everyone is convinced. Some researchers argue that genetic or environmental variables could’ve prompted some of these behaviors. The chimpanzees weren’t all the same subspecies. They ranged from coastal Guinea to Uganda, 2,700 miles apart—far enough, some suggest, that ecological differences could have influenced the primates’ activities.

But a new way of thinking about wildlife behavior and group culture, less centered on humans, was taking root. And as Whiten and others built on their initial work, skeptics found claims harder to dismiss—especially when it came to creatures longer than city buses that use sound to find their prey a mile below the sea’s surface.

“Whoa, whoa! Right here!” Shane Gero shouts, and begins counting. Eight sperm whales bob off our port side, half-submerged in the cobalt Caribbean. They’re gunmetal gray and as smooth and cylindrical as airplane fuselages. The whales are taking a breather—literally. They’ve just surfaced to draw oxygen deep into their enormous, squared-off heads. Soon they’ll dive and use some of that air to converse.

We’re aboard Balaena, a 40-foot sailboat, swaying offshore of the West Indies island nation of Dominica. The tiny country’s rain-soaked peaks, now shrouded in mist, are partly why we’re here. Those small green mountains block gales and keep deep leeward waters calm—ideal conditions for studying sperm whales. And Gero, crisscrossing the deck barefoot in board shorts, has studied more sperm whale families up close than perhaps any human in history.

Since 2005, the adjunct professor at Denmark’s Aarhus University and Canada’s Carleton and Dalhousie Universities has come to this glittering swirl of sargassum and spray to study these leviathans. Rather than finding a “monomaniac incarnation” of “malicious agencies” as Herman Melville described the sperm whale in Moby-Dick, Gero sees peaceful, playful animals. He can identify dozens on sight. There’s Canopener, who toys with researchers, pulling close to their vessel before rolling sideways to eyeball Gero’s crew. There’s Digit, who almost perished after swimming through fishing gear that lassoed her tail, nearly amputating it while preventing her from diving to eat. (She’s since healed.) The one with the serrated fluke is called Knife; the one with the weird scoop in his was Spoon.

The whales he knows are local “island specialists,” Gero tells me. He follows them as they move through underwater canyons off Dominica, between the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique. He has tracked them sleeping, giving birth, nursing, making their first dives, playing with cousins, dying. He’s recorded them swimming deeper than most submarines travel. He knows their lives so intimately his kids at home can recite their names.

But today, after more than a week at sea, we woke to find the locals gone, replaced by the eight outsiders riding swells around us. Gero is gregarious by nature, yet this is the most excited I’ve seen him. He’s shouting for students to drop underwater recorders called hydrophones. He warns them to get their cameras ready to photograph flukes, which, like fingerprints, help identify individual whales as they dive.

These new whales are animals he barely knows, itinerant vagabonds from a second whale community. They occasionally share space with the regulars, but never interact with them. To me, they’re sleek and glorious but not so different from the local whales we spotted yesterday. To Gero, they are unmistakable evidence that Dominica is home to parallel whale traditions—two cultures as divergent as farmers and nomadic hunter-gatherers.

The roots of this knowledge come from the man helming our sailboat, Gero’s mentor, Hal Whitehead. Curly mopped, hat brim blown skyward by wind, the professor at Dalhousie University steadies our craft with one eye on our visitors. Sperm whales travel in lifelong, female-led social units (males are squeezed out in their early teens) of about a dozen. In the 1980s and 1990s, Whitehead tracked some of these social units across the Galápagos, partly as an excuse to live at sea. Then “I just became really interested in them,” he says. He and Luke Rendell, a researcher at the University of St. Andrews, started unspooling their cultural mysteries by documenting patterns of sperm whale chatter.

Sperm whales use the world’s largest brains to operate nature’s largest sonar system. They send pressurized air through their snout, creating clicking sounds. They string these clicks together in rhythmic codas, rather like Morse code. Each coda lasts seconds or less. Some are three clicks; some may be a dozen or more. Over decades Whitehead recorded clicks by the thousands.

He had no clue what the whales were saying, but one day in his lab in Nova Scotia, Whitehead created a chart summarizing recording data from all these whale groups. He spotted a trend: Roughly half made a common repertoire of calls. Their codas had similar patterns. Other units used different arrangements. “I was blown away,” Whitehead recalls. He bounded up concrete steps to Rendell’s office. Rendell got it too. These small whale units were part of something bigger—whale clans of hundreds or thousands. And each clan was speaking its own dialect.

Why would these animals, many of which had never met, have shared common calls? It’s a group moniker, the men theorized, a way to say, “I’m one of you.” They knew small groups spent time with others in their clan, but never with outsiders. And in the inky black of the sea, sound is how they’d see who was around.

Whitehead suspected click-codas were similar to human markers of cultural identity. Think, he says, of the gear worn by English Premier League soccer fans. “The Manchester United supporters parade around with a red scarf, the Manchester City with a blue scarf,” Whitehead tells me as dusk settles over the Caribbean. They don’t all know each other, and don’t mingle. Yet fans find their way to pubs to watch matches together. “It suggests this higher-level thing that’s really important to the whales,” Whitehead says.

Over time he, Rendell, and others also documented that whales in two distinct clans in the Galápagos had startlingly different habits. In one, whales cruised the sea in meandering formations, while in the other they swam in straighter lines. One clan stayed close to land, the other moved farther offshore. During El Niño periods, when waters warmed, whales in both clans struggled to get enough food, but one clan had a harder time than the other.

For whales, it appears “there is this boundary between us who learn from each other and do things one way,” Gero explains, “and they who don’t learn from us and do things differently.”

The idea that whales have cultures at all, let alone that they segregate themselves into cultural groups as humans do, was controversial when Whitehead and Rendell presented it in 2001. “It is sad to see such rich empirical material, about such wonderful creatures, harnessed to such an impoverished theoretical agenda,” one British anthropologist sneered.

Twenty years later, some skepticism remains. “I would never say that sperm or killer whales do not have culture, but I would say that the evidence for culture is stronger in many other animal species,” such as humpbacks and songbirds, says Peter Tyack, a scientist with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who studies cetacean communication. Genetics, animal development, and the environment can work in complex ways that make it hard to definitively link behavior to culture. “It is essential for scientists to be honest and humble about how little we know about the cultures of any animal species.”

And yet whale scientists increasingly embrace Whitehead’s view, says Sarah Mesnick, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “It’s gaining acceptance because more and more people are observing it,” she says.

Gero, for example, found similar divisions among sperm whale clans in an entirely different sea than his mentor: the Caribbean. And Gero’s ability to drill down into life with individual whales has strengthened Whitehead’s case.

One afternoon we spot a female sperm whale named Rounder. She’s floating at the surface with two calves, only one of which is hers. Baby whales don’t dive deep for squid, Gero explains, so an adult protector stays topside as the unit hunts. We’re watching Rounder babysit.

Every unit does this differently. Some let the young slip beneath their bellies to suckle. In some units, calves get watched by nonrelatives, but get milk only from mom. In Rounder’s group, moms and grandmothers share babysitting and nursing duties, but only for calves in their bloodline. In another, one female plays wet nurse to two calves at once—even though neither is hers.

Gero also discovered that small units within clans appear to emit family-specific codas, almost like surnames, while individuals communicate in click patterns with subtle, signature variations, like first names. Using nothing but clicks, Gero can tell which whale in a unit is speaking about 80 percent of the time—“way better than random chance,” he says.

Gero even recorded baby sperm whales making random clicks before winnowing their repertoire. They were zeroing in on their clan’s dialect, like infants babbling before saying “mama.” They were acquiring cultural norms before him in real time.

Back home one afternoon, I sit down to sample some whale culture for myself. Slapping on headphones, I click a computer file. What I hear next is deep and guttural, like the low rumble of a bass saxophone dipped in water. The burbling wail begins to climb until it reaches a pinched-off, airy screech, like a child blowing a conch. Soon the sounds change entirely, becoming dark and melodic, then ethereal and wispy. I hear what sounds like a squeegee stroking glass. A high note ends with a chirp that recalls the tiny squeak that slips from a yawning puppy. A bass croak rolls out like a long, slow burp.

This is the song of a male humpback whale. It was sent to me by Ellen Garland, a colleague of Rendell’s at the University of St. Andrews. A few years ago a tune much like this one swept across the South Pacific, igniting a full-blown cultural revolution.

Male humpbacks pick up songs from one another. And male humpbacks are into fresh beats. Like pop culture fanatics, they’re always chasing that next sound, eager to find a trendy new tune. The speed with which they adopt new sonic arrangements “is astounding,” Garland tells me one morning when I reach her by phone in the United Kingdom. So too is a song’s geographic reach. One song can spread across an ocean basin.

Scientists have been studying humpback songs in earnest since at least the 1960s. That’s when biologist Roger Payne famously towed a hydrophone behind a sailboat in the dead of night off Bermuda, capturing eerie, echoing moans. Humpbacks trumpet, bark, and groan, and make noises like mewling kittens. But in their basic structure, humpbacks’ sophisticated symphonies can be spookily similar to our own.

Humpback songs employ rhyme and rhythm, phrasing and melody. There are themes followed by variations and returns to those original statements. Whales have been around for 50 million years. Before recent decades, there was little possibility that humans and humpbacks had heard each other’s melodies. “Yet whales use many of the same laws of composition in their songs that we use in ours,” Payne wrote in his book Among Whales. A single whale song may last half an hour. A single whale may sing all afternoon.

Garland came to her whale insights by way of the sky. For a college project in her native New Zealand, she’d classified the vocalizations of song thrushes, discovering a talent for acoustic cataloging. Years later she applied her auditory skills to whales.

Humpback songs are part of mating rituals. And researchers had long assumed all humpbacks in an area shared the same song each year. “That’s not what we found at all,” Garland says. Using spectrograms that transform sound frequencies into pictures, revealing the amplitude and patterns of whale songs, she analyzed years of whale tunes across the South Pacific. She reviewed humpback songs in French Polynesia, then moved toward songs from Australia, some 3,700 miles away.

She noticed something curious. Songs appeared to originate in Australia. They would evolve as whales began to tinker. Like composers, they’d add hiccups or whistles or new verses. But then, like a pop song that suddenly catches fire and takes a hemisphere by storm, this new song would roll from whale to whale across thousands of miles, moving from New Caledonia to Tonga, then a year later to the Cook Islands.

The tune that wound up in French Polynesia would be similar to the song that first appeared in Australia. Despite minor tinkering along the way, the final version was not much different from an acoustic cover of an original hit. Yet it was unrecognizable from the song it was replacing. This new production was as unlike its predecessor “as the Rolling Stones and Justin Bieber,” Garland tells me.

Garland was floored. She suspects whales respond to the song’s novelty. In the same way hipsters seek out new indie bands, male whales appear to pick up new tunes to stand out from the crowd. But eventually all of the males will abandon their song and switch to the novel one.

That kind of progression once was unexpected. It’s a rare moment in the animal kingdom of rapid transformational change—a true cultural revolution. Birds moving into another flock tend to take up calls of their hosts, Garland says. But when a whale hits open-mike night with a hot new number, locals drop their old ballad to belt out a new one. Garland offers an analogy: Imagine moving to a neighboring country where everyone you meet swaps his or her national anthem for yours.

“It is incredibly, incredibly weird,” she says.

The big question now is whether some of these whale communities will survive long enough for us to understand their cultures. Few know this better than Ford, the Canadian killer whale biologist. As a teenager, he swept popcorn off the floor and fed seals and belugas at the Vancouver Aquarium. He would go on to discover distinct orca dialects before leading West Coast whale research for the Canadian government.

When I ask about resilience during one of our many talks, Ford shares a story. Killer whales travel in matrilineal family pods for life and learn how and what to eat by watching their kin. In 1970, when wild orcas in the region were still being caught for marine parks, wranglers drove five killer whales into a British Columbia cove. Two were taken to a marine park. The remaining three refused to eat the salmon offered by caretakers. One eventually died. Only after 79 days did the survivors start eating fish.

The whales were “caught in this behavioral rut,” Ford tells me. The caretakers didn’t know killer whales in the Northwest represent three different diets: southern- and northern-resident salmon-eaters; offshore shark-eaters; and Bigg’s killer whales, which hunt only marine mammals. Unlike some other cetaceans whose culture offers them flexibility, these killer whales are unwilling or unable to switch food even when options dwindle, much as Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen beat Robert Falcon Scott, a Brit, to the South Pole by eating his sled dogs, which Scott refused to do. “It’s just an example of how ingrained these cultures are,” Ford says.

That’s partly why, in 2019, more than two dozen scientists, including Ford, Garland, Whiten, and Whitehead, called for a sea change in global conservation. In the journal Science they urged the world to incorporate culture into wildlife management decisions. The Convention on Migratory Species already is developing a plan for South American countries to protect sperm whales in the eastern Pacific by focusing on what individual clans require. Such approaches are “essential to maintaining the natural diversity and integrity of Earth’s rich ecosystems,” the authors argue.

My region is trying, but another culture is in the way: ours.

The United States and Canada already treat the southern and northern fish-eating whales as distinct populations despite their genetic similarities and proximity. The belly-rubbing, head-knocking northern whales aren’t the same as the high-flying acrobatic pods that sometimes appear outside Seattle. We recognize that oceans—and humans—need both.

But they face starkly different futures. The number of killer whales in the more rural north has skyrocketed since the 1970s. The southern whales are critically endangered.

Decimated by culling for marine parks in the 1960s and early ’70s, the southern residents now battle noise from boat traffic. Development crowds their shores, dumps silt in their waters, and brings pollution. Toxic chemicals, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), have built up in their blubber. All of that is made far worse by a drastic shortage of food as Chinook populations plummet, thanks to years of fishing, dambuilding, more development, and climate change.

These sophisticated alien beings are, quite literally, vanishing before our eyes, not so different from South America’s pre-Inca Tiwanaku Empire, which left no written record of its 12th-century collapse. We don’t know what might disappear with them. We can’t explain why they act as they do or why that’s so unlike other whales. But we’re at least beginning to acknowledge that what’s at stake is rich and important in ways we may not yet fully comprehend.

How You Can Help

Planet Possible

Check out National Geographic’s new solutions-oriented initiative: natgeo.com/planet. These nonprofits working on whale issues are among those we’ve supported over the years:

The Dominica Sperm Whale Project

The project’s researchers have spent thousands of hours observing sperm whale families in the Caribbean to better understand their unique cultures. thespermwhaleproject.org

Whale Trust Maui

Scientists here study natural behavior patterns associated with reproduction and communication, including humpback singing, to develop better protection methods. whaletrust.org

Alaska Whale Foundation

Founded in 1996 to study humpback whales in southeast Alaska, AWF now conducts research on an array of marine animals and coastal ecosystems throughout the region. alaskawhalefoundation.org

This story appears in the May 2021 issue of National Geographic magazine.

Staff writer Craig Welch wrote about a cross-country road trip in electric cars for the April 2020 issue. Photographer Brian Skerry’s images of mako sharks appeared in the August 2017 issue.

Additional funding for the photography in this article was provided by the Philip Stephenson Foundation and by Focused on Nature.

The National Geographic Society is committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world. Learn more about the Society’s support of ocean Explorers.

The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funded Explorer Brian Skerry’s work. Learn more about the Society’s support of ocean Explorers.