The magnetic chomp of a Venus flytrap—and more dispatches from science’s front lines

New discoveries in biomagnetism, COVID-19’s environmental costs, and a dinosaur’s wing

When the Venus flytrap’s jawlike leaves are stimulated by prey, the plant produces a small magnetic field, new research has found. Such fields have been detected in only two other plants: a bean and a single-celled alga. The scientists who discovered this field think it’s a by-product of electrical impulses that trigger the flytrap’s leaves to close. Biomagnetism of this type has been studied extensively in the human brain but is less understood in plants. —Annie Roth

PPE where it shouldn’t be

The fight against COVID-19 has had environmental costs. Mountains of personal protective equipment have been discarded—at one point, an estimated 3.4 billion masks a day. What shielded humans now harms wildlife, like the perch trapped in this glove in the Netherlands and countless birds snared in mask straps. —AR

(For young climate activists, the pandemic is the defining moment for action)

From a dino’s wing?

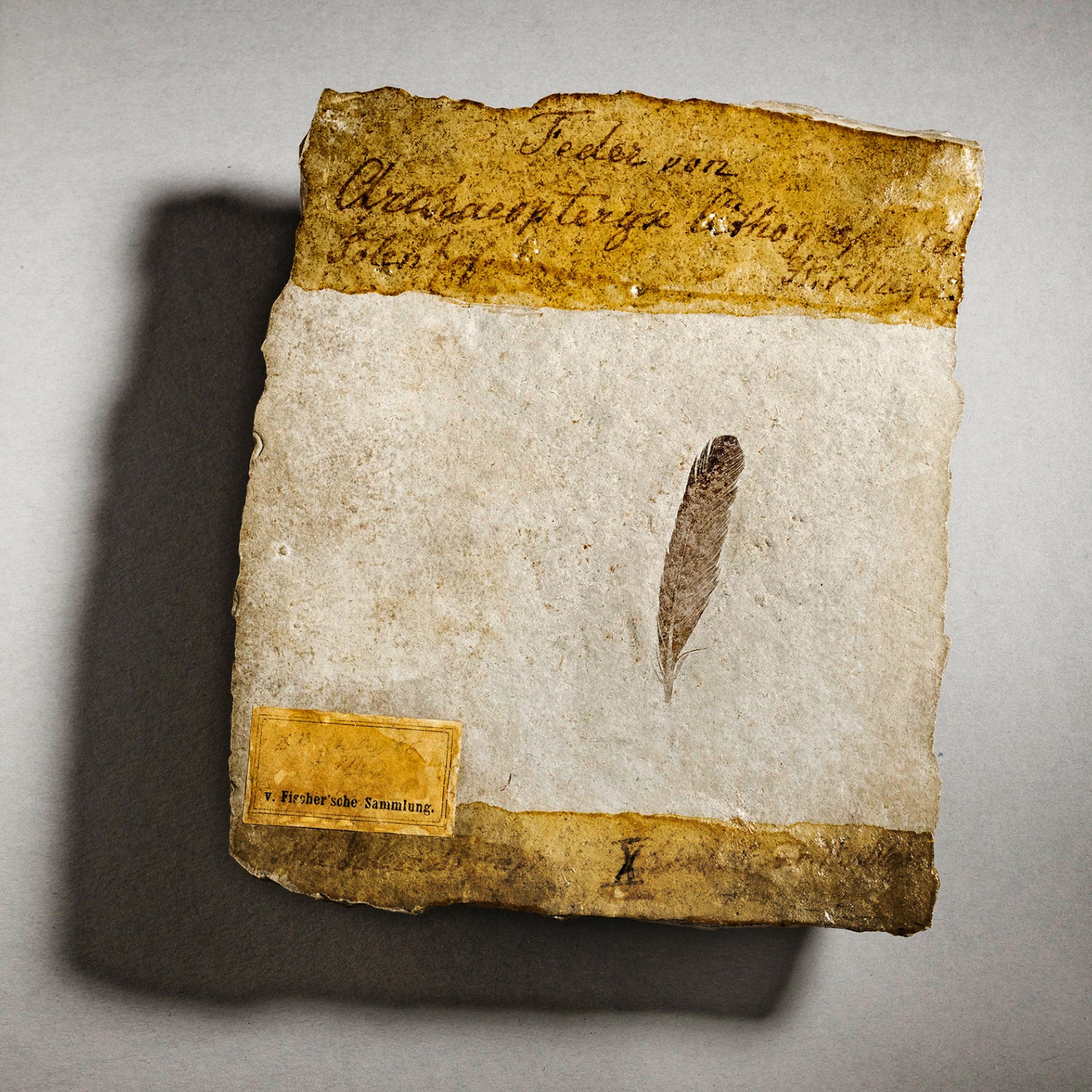

Since it emerged from a Bavarian limestone quarry in 1861, the first known fossilized feather has been a paleontology icon: shockingly similar to modern bird feathers yet unfathomably ancient. The 150-million-year-old, isolated plume was the first fossil ever called Archaeopteryx lithographica—a name that now refers to a type of feathered dinosaur discovered less than two miles away in the same rock layers as the original feather. But did Archaeopteryx the dinosaur really shed its namesake feather? National Geographic Explorer Ryan Carney, a paleontologist at the University of South Florida, says the answer is a resounding yes. In a paper published last fall in Scientific Reports, Carney contends that the feather not only belonged to an Archaeopteryx but also specifically helped form the upper surface of the dinosaur’s left wing. Now Carney is reconstructing how Archaeopteryx flapped its wings, to test whether it could have flown under its own power. —Michael Greshko

This story appears in the September 2021 issue of National Geographic magazine.