Unseen Titanic

At 2:20 a.m. on April 15, 1912, the “unsinkable” R.M.S. Titanic disappeared beneath the waves, taking with her 1,500 souls. One hundred years later, new technologies have revealed the most complete and most intimate images of the famous wreck.

The wreck sleeps in darkness, a puzzlement of corroded steel strewn across a thousand acres of the North Atlantic seabed. Fungi feed on it. Weird colorless life-forms, unfazed by the crushing pressure, prowl its jagged ramparts. From time to time, beginning with the discovery of the wreck in 1985 by Explorer-in-Residence Robert Ballard and Jean-Louis Michel, a robot or a manned submersible has swept over Titanic’s gloomy facets, pinged a sonar beam in its direction, taken some images—and left.

In recent years explorers like James Cameron and Paul-Henry Nargeolet have brought back increasingly vivid pictures of the wreck. Yet we’ve mainly glimpsed the site as though through a keyhole, our view limited by the dreck suspended in the water and the ambit of a submersible’s lights. Never have we been able to grasp the relationships between all the disparate pieces of wreckage. Never have we taken the full measure of what’s down there.

(Where Did Titanic Survivors Go?)

Until now. In a tricked-out trailer on a back lot of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), William Lange stands over a blown-up sonar survey map of the Titanic site—a meticulously stitched-together mosaic that has taken months to construct. At first look the ghostly image resembles the surface of the moon, with innumerable striations in the seabed, as well as craters caused by boulders dropped over millennia from melting icebergs.

On closer inspection, though, the site appears to be littered with man-made detritus—a Jackson Pollock-like scattering of lines and spheres, scraps and shards. Lange turns to his computer and points to a portion of the map that has been brought to life by layering optical data onto the sonar image. He zooms in, and in, and in again. Now we can see the Titanic’s bow in gritty clarity, a gaping black hole where its forward funnel once sprouted, an ejected hatch cover resting in the mud a few hundred feet to the north. The image is rich in detail: In one frame we can even make out a white crab clawing at a railing.

Here, in the sweep of a computer mouse, is the entire wreck of the Titanic—every bollard, every davit, every boiler. What was once a largely indecipherable mess has become a high-resolution crash scene photograph, with clear patterns emerging from the murk. “Now we know where everything is,” Lange says. “After a hundred years, the lights are finally on.”

Bill Lange is the head of WHOI’s Advanced Imaging and Visualization Laboratory, a kind of high-tech photographic studio of the deep. A few blocks from Woods Hole’s picturesque harbor, on the southwestern elbow of Cape Cod, the laboratory is an acoustic-tiled cave crammed with high-definition television monitors and banks of humming computers. Lange was part of the original Ballard expedition that found the wreck, and he’s been training ever more sophisticated cameras on the site ever since.

This imagery, the result of an ambitious multi-million-dollar expedition undertaken in August-September 2010, was captured by three state-of-the-art robotic vehicles that flew at various altitudes above the abyssal plain in long, preprogrammed swaths. Bristling with side-scan and multibeam sonar as well as high-definition optical cameras snapping hundreds of images a second, the robots systematically “mowed the lawn,” as the technique is called, working back and forth across a three-by-five-mile target area of the ocean floor. These ribbons of data have now been digitally stitched together to assemble a massive high-definition picture in which everything has been precisely gridded and geo-referenced.

“This is a game-changer,” says National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) archaeologist James Delgado, the expedition’s chief scientist. “In the past, trying to understand Titanic was like trying to understand Manhattan at midnight in a rainstorm—with a flashlight. Now we have a site that can be understood and measured, with definite things to tell us. In years to come this historic map may give voice to those people who were silenced, seemingly forever, when the cold water closed over them.”

What is it about the wreck of the R.M.S. Titanic? Why, a century later, do people still lavish so much brainpower and technological ingenuity upon this graveyard of metal more than two miles beneath the ocean surface? Why, like Pearl Harbor, ground zero, and only a few other hallowed disaster zones, does it exert such a magnetic pull on our imagination?

For some the sheer extravagance of Titanic’s demise lies at the heart of its attraction. This has always been a story of superlatives: A ship so strong and so grand, sinking in water so cold and so deep. For others the Titanic’s fascination begins and ends with the people on board. It took two hours and 40 minutes for the Titanic to sink, just long enough for 2,208 tragic-epic performances to unfold, with the ship’s lights blazing. One coward is said to have made for the lifeboats dressed in women’s clothing, but most people were honorable, many heroic. The captain stayed at the bridge, the band played on, the Marconi wireless radio operators continued sending their distress signals until the very end. The passengers, for the most part, kept to their Edwardian stations. How they lived their final moments is the stuff of universal interest, a danse macabre that never ends.

But something else, beyond human lives, went down with the Titanic: An illusion of orderliness, a faith in technological progress, a yearning for the future that, as Europe drifted toward full-scale war, was soon replaced by fears and dreads all too familiar to our modern world. “The Titanic disaster was the bursting of a bubble,” James Cameron told me. “There was such a sense of bounty in the first decade of the 20th century. Elevators! Automobiles! Airplanes! Wireless radio! Everything seemed so wondrous, on an endless upward spiral. Then it all came crashing down.”

The mother of all shipwrecks has many homes—literal, legal, and metaphorical—but none more surreal than the Las Vegas Strip. At the Luxor Hotel, in an upstairs entertainment court situated next to a striptease show and a production of Menopause the Musical, is a semipermanent exhibition of Titanic artifacts brought up from the ocean depths by RMS Titanic, Inc., the wreck’s legal salvager since 1994. More than 25 million people have seen this exhibit and similar RMST shows that have been staged in 20 countries around the world.

I spent a day at the Luxor in mid-October, wandering among the Titanic relics: A chef’s toque, a razor, lumps of coal, a set of perfectly preserved serving dishes, innumerable pairs of shoes, bottles of perfume, a leather gladstone bag, a champagne bottle with the cork still in it. They are mostly ordinary objects made extraordinary for the long, terrible journey that brought them to these clean Plexiglas cases.

I passed through a darkened chamber kept as cold as a meat locker, with a Freon-fed “iceberg” that visitors can go up to and touch. Piped-in sighs and groans of rending metal contributed to the sensation of being trapped in the belly of a fatally wounded beast. The exhibit’s centerpiece, however, was a gargantuan slab of Titanic’s hull, known as the “big piece,” that weighs 15 tons and was, after several mishaps, hoisted by crane from the seabed in 1998. Studded with rivets, ribbed with steel, this monstrosity of black metal reminded me of a T. rex at a natural history museum: impossibly huge, pinned and braced at great expense—an extinct species hauled back from a lost world.

The RMST exhibit is well-done, but over the years many marine archaeologists have had harsh words for the company and its executives, calling them grave robbers, treasure hunters, carnival barkers—and worse. Robert Ballard, who has long argued that the wreck and all its contents should be preserved in situ, has been particularly caustic in his criticism of RMST’s methodologies. “You don’t go to the Louvre and stick your finger on the Mona Lisa,” Ballard told me. “You don’t visit Gettysburg with a shovel. These guys are driven by greed—just look at their sordid history.”

In recent years, however, RMST has come under new management and has taken a different course, shifting its focus away from pure salvage toward a long-term plan for approaching the wreck as an archaeological site—while working in concert with scientific and governmental organizations most concerned with the Titanic. In fact, the 2010 expedition that captured the first view of the entire wreck site was organized, led, and paid for by RMST. In a reversal from years past, the company now supports calls for legislation creating a protected Titanic maritime memorial. Late in 2011 RMST announced plans to auction off its entire $189 million collection of artifacts and related intellectual property in time for the disaster’s hundredth anniversary—but only if it can find a bidder willing to abide by the stringent conditions imposed by a federal court, including that the collection be kept intact.

I met RMST’s president, Chris Davino, at the company’s artifacts warehouse, tucked next to a dog grooming parlor in a nondescript block on the edge of Atlanta’s Buckhead district. Deep inside the climate-controlled brick building, a forklift trundled down the long aisles of industrial shelving stacked with meticulously labeled crates containing relics—dishes, clothing, letters, bottles, plumbing pieces, portholes—that were retrieved from the site over the past three decades. Here Davino, a dapper, Jersey shore-raised “turnaround professional” who has led RMST since 2009, explained the company’s new tack. “For years, the only thing that all the voices in the Titanic community could agree on was their disdain of us,” he said. “So it was time to reassess everything. We had to do something beyond artifact recovery. We had to stop fighting with the experts and start collaborating with them.”

Which is exactly what’s happened. Government agencies such as NOAA that were formerly embroiled in lawsuits against RMST and its parent company, Premier Exhibitions, Inc., are now working directly with RMST on various long-range scientific projects as part of a new consortium dedicated to protecting the wreck site. “It’s not easy to thread the needle between preservation and profit,” says Dave Conlin, chief marine archaeologist at the National Park Service, another agency that had been vehemently critical of the company. “RMST deserved the flak they got in years past, but they also deserve credit for taking this new leap of faith.”

Scholars praise RMST for recently hiring one of the world’s preeminent Titanic experts to analyze the 2010 images and begin to identify the many unsorted puzzle pieces on the ocean floor. Bill Sauder is a gnome-like man with thick glasses and a great shaggy beard that flexes and snags on itself when he laughs. His business card identifies him as a “director of Titanic research,” but that doesn’t begin to hint at his encyclopedic mastery of the Titanic’s class of ocean liners. (Sauder himself prefers to say that he is RMST’s “keeper of odd knowledge.”)

When I met him in Atlanta, he was parked at his computer, attempting to make head or tail of a heap of rubbish photographed in 2010 near the Titanic’s stern. Most Titanic expeditions have focused on the more photogenic bow section, which lies over a third of a mile to the north of most of the wreckage, but Sauder thinks that the area in the vicinity of the stern is where the real action will likely be concentrated in years to come—especially with the new RMST images providing a clearer guide. “The bow’s very sexy, but we’ve been to it hundreds of times,” Sauder said. “All this wreckage here to the south is what I’m interested in.”

In essence Sauder was hunting for anything recognizable, any pattern amid the chaos around the stern. “We like to picture shipwrecks as Greek temples on a hill—you know, very picturesque,” he told me. “But they’re not. They’re ruined industrial sites: piles of plates and rivets and stiffeners. If you’re going to interpret this stuff, you gotta love Picasso.”

Sauder zoomed in on the image at hand, and within a few minutes had solved at least a small part of the mystery near the stern: Lying atop the wreckage was the crumpled brass frame of a revolving door, probably from a first-class lounge. It is the kind of painstaking work that only someone who knows every inch of the ship could perform—a tiny part of an enormous Where’s Waldo? sleuthing project that could keep Bill Sauder busy for years.

In late October I found myself in Manhattan Beach, California, inside a hangar-size film studio where James Cameron, surrounded by dazzling props and models from his 1997 movie, Titanic, had assembled a roundtable of some of the world’s foremost nautical authorities—quite possibly the most illustrious conclave of Titanic experts ever gathered. Along with Cameron, Bill Sauder, and RMST explorer Paul-Henry Nargeolet, the roundtable boasted Titanic historian Don Lynch and famed Titanicartist Ken Marschall, along with a naval engineer, a Woods Hole oceanographer, and two U.S. Navy architects.

Cameron could more than hold his own in this select company. A self-described “rivet-counting Titanic geek,” the filmmaker has led three expeditions to the site. He developed and piloted a new class of nimble, fiber-spooling robots that brought back never before seen images of the ship’s interior, including tantalizing glimpses of the Turkish bath and some of the opulent staterooms.

Cameron has white hair and a close-clipped white goatee, and when he’s wound up on Titanic matters, a certain Melvillean intensity weighs on his brow. Cameron has also filmed the wreck of the Bismarck and is now building a submarine to take him and his cameras to the Mariana Trench. But the Titanic still holds him; he keeps swearing off the subject, only to return. “There’s this very strange mixture of biology and architecture down there—this sort of biomechanoid quality,” he told me at his Malibu compound. “I think it’s gorgeous and otherworldly. You really feel like this is something that’s gone to Tartarus—to the underworld.”

At Cameron’s request, the two-day roundtable would concentrate entirely on forensics: Why did the Titanic break up the way she did? Precisely where did the hull fail? At what angle did the myriad components smash into the seabed? It was to be a kind of inquest, in other words, nearly a hundred years after the fact.

“What you’re looking at is a crime scene,” Cameron said. “Once you understand that, you really get sucked into the minutiae. You want to know: How’d it get like that? How’d the knife wind up over here and the gun over there?”

Perhaps inevitably, the roundtable took off in esoteric directions—with discussion of glide ratios, shearing forces, turbidity studies. Listeners lacking an engineering sensibility would have extracted one indelible impression from the seminar: Titanic’s final moments were hideously, horrifically violent. Many accounts depict the ship as “slipping beneath the ocean waves,” as though she drifted tranquilly off to sleep, but nothing could be further from the truth. Building on many years of close analysis of the wreck, and employing state-of-the-art flooding models and “finite element” simulations used in the modern shipping industry, the experts painted a gruesome portrait of Titanic’s death throes.

The ship sideswiped the iceberg at 11:40 p.m., buckling portions of the starboard hull along a 300-foot span and exposing the six forward watertight compartments to the sea. From this moment onward, sinking was a certainty. The demise may have been hastened, however, when crewmen pushed open a gangway door on the port side in an aborted attempt to load lifeboats from a lower level. Since the ship had begun listing to port, they could not reclose the massive door against gravity, and by 1:50 a.m., the bow had settled enough to allow seawater to rush in through the gangway.

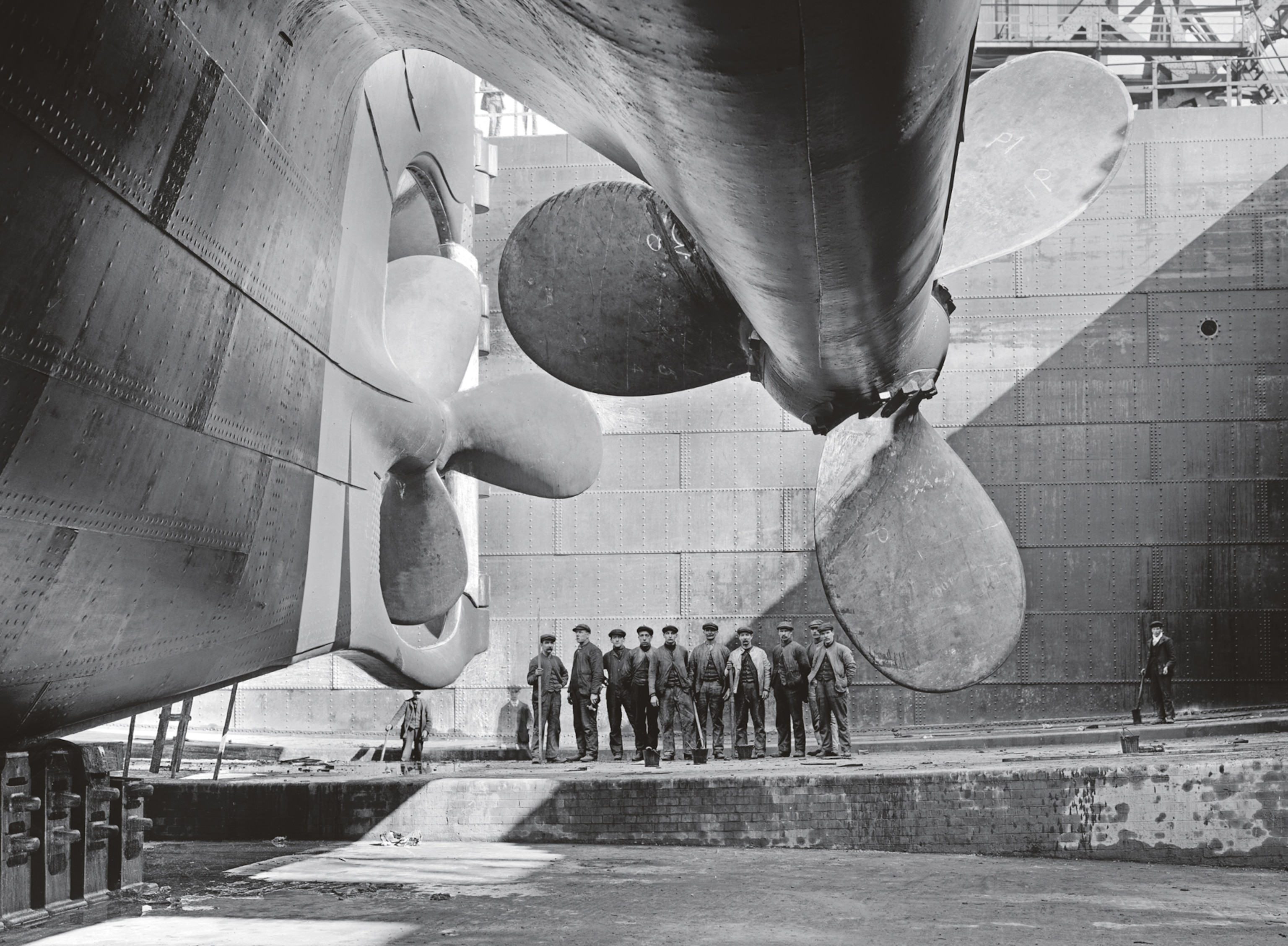

By 2:18, with the last lifeboat having departed 13 minutes earlier, the bow had filled with water and the stern had risen high enough into the air to expose the propellers and create catastrophic stresses on the middle of the ship. Then the Titanic cracked in half.

Cameron stood up and demonstrated how it happened. He grabbed a banana and began to wrench it in his hands: “Watch how it flexes and pooches in the middle before it breaks—see that?” The banana skin at the bottom, which was supposed to represent the doubly reinforced bottom of the hull, was the last part to snap.

Once released from the stern section, the bow shot for the bottom at a fairly steep angle. Gaining velocity as it dropped, parts began to shear away: Funnels snapped. The wheelhouse crumbled. Finally, after five minutes of relentless descent, the bow nosed into the mud with such massive force that its ejecta patterns are still visible on the seafloor today.

The stern, lacking a hydrodynamic leading edge like the bow, descended even more traumatically, tumbling and corkscrewing as it fell. A large forward section, already weakened by the fracture at the surface, completely disintegrated, spitting its contents into the abyss. Compartments exploded. Decks pancaked. Hull plates ripped out. The poop deck twisted back over itself. Heavier pieces such as the boilers dropped straight down, while other pieces were flung off “like Frisbees.” For more than two miles, the stern made its tortured descent—rupturing, buckling, warping, compressing, and gradually disintegrating. By the time it hit the ocean floor, it was unrecognizable.

Sitting back down, Cameron popped a pinched piece of banana in his mouth and ate it. “We didn’t want the Titanic to have broken up like this,” he said. “We wanted her to have gone down in some kind of ghostly perfection.”

Listening to this learned disquisition on the Titanic’s death, I kept wondering: What happened to the people still on board as she sank? Most of the 1,496 victims died of hypothermia at the surface, bobbing in a patch of cork life preservers. But hundreds of people may still have been alive inside, most of them immigrant families in steerage class, looking forward to a new life in America. How did they, during their last moments, experience these colossal wrenchings and shudderings of metal? What would they have heard and felt? It was, even a hundred years later, too awful to contemplate.

St. John’s, Newfoundland, is another of Titanic’s homes. On June 8, 1912, a rescue ship returned to St. John’s bearing the last recovered Titanic corpse. For months, deck chairs, pieces of wood paneling, and other relics were reported to have washed up on the Newfoundland coast.

I had hoped to pay my respects to the people who literally went down with the ship by flying to the wreck site from St. John’s with the International Ice Patrol, the agency created in the disaster’s aftermath to keep watch for icebergs in the North Atlantic sea lanes. When a nor’easter canceled all flights, I found my way instead to a tavern in the George Street district, where I was treated to a locally made vodka distilled with iceberg water. To complete the effect, the bartender plopped into my glass an angular nub of ice chipped from an iceberg, supposedly calved from the same Greenlandic glacier that birthed the berg that sank Titanic. The ice ticked and fizzed in my glass—the exhalations, I was told, of ancient atmospheres trapped inside.

I could still get a little closer, physically and figuratively, to those who rest forever with the ship. A few years before the disaster, Guglielmo Marconi built a permanent wireless station on a desolate, wind-battered spit south of St. John’s, called Cape Race. Locals claim that the first person to receive the distress signal from the sinking ship was Jim Myrick, a 14-year-old wireless apprentice at the station who went on to a career with the Marconi Company. Initially, the transmission came in as a standard emergency code, CQD. But then Cape Race received a new signal, seldom used before: SOS.

One morning at Cape Race, amid the carcasses of old Marconi machines and crystal receivers, I met David Myrick, Jim’s great-nephew, a marine radio operator and the last of a proud line of antique communicators. David said his uncle never spoke about the night the Titanic sank until he was a frail old man. By that point, Jim had lost his hearing so completely that the only way the family could converse with him was through Morse code—manipulating a smoke detector to produce high-pitched dots and dashes. “A Marconi man to the end,” David said. “He thought in Morse code—hell, he dreamed in it.”

We went out by the lighthouse and looked over the cold sea, which crashed into the cliffs below. An oil tanker cruised in the distance. Farther out, on the Grand Banks, new icebergs had been reported. Farther out still, somewhere beyond the bulge of the horizon, lay the most famous shipwreck in the world. My mind raced with thoughts of signals bouncing in the ionosphere—the propagation of radio waves, the cry of ages submerged in time. And I imagined I could hear the voice of the Titanic herself: A vessel with too much pride in her name, sprinting smartly toward a new world, only to be mortally nicked by something as old and slow as ice.