Our bodies are unique. Our cancers are too.

Breast Cancer Awareness Month celebrates, in part, how much better we understand how cancer behaves. But the great challenge for researchers remains: Cancer has many faces.

The body is a brilliant machine, designed to be strong and resilient. It heals from wounds and fends off sickness. It provides us with T cells, which patrol the body to recognize and destroy abnormalities and invaders. Most of the time, the system self-regulates without us even being aware of the work it’s doing. But sometimes, the system glitches: Cancer happens.

As Dr. Jedd Wolchok, a medical oncologist who treated my cancer and the guy who eventually saved my life, explains it: “The idea is that there are several phases in immune surveillance. The first is elimination. Tumor arises. Immune system sees it. It’s gotten rid of. End of story. The next phase is equilibrium, where a tumor arises, the immune system sees it, can’t quite get rid of it, but the cancer doesn’t do any more; it doesn’t spread.

“Then there’s the final E— escape. Escape is what we deal with, unfortunately, on a day-to-day basis. The tumor has learned skills that allow it to evade the immune system.”

Cancerous cells, clever devils that they are, contain an inhibitory signal that scrambles that immune system response. That’s what allows cancer to survive and the reason that cancer cells spread—the T cells that are supposed to destroy them don’t know to kill them.

Officially targeting cancer

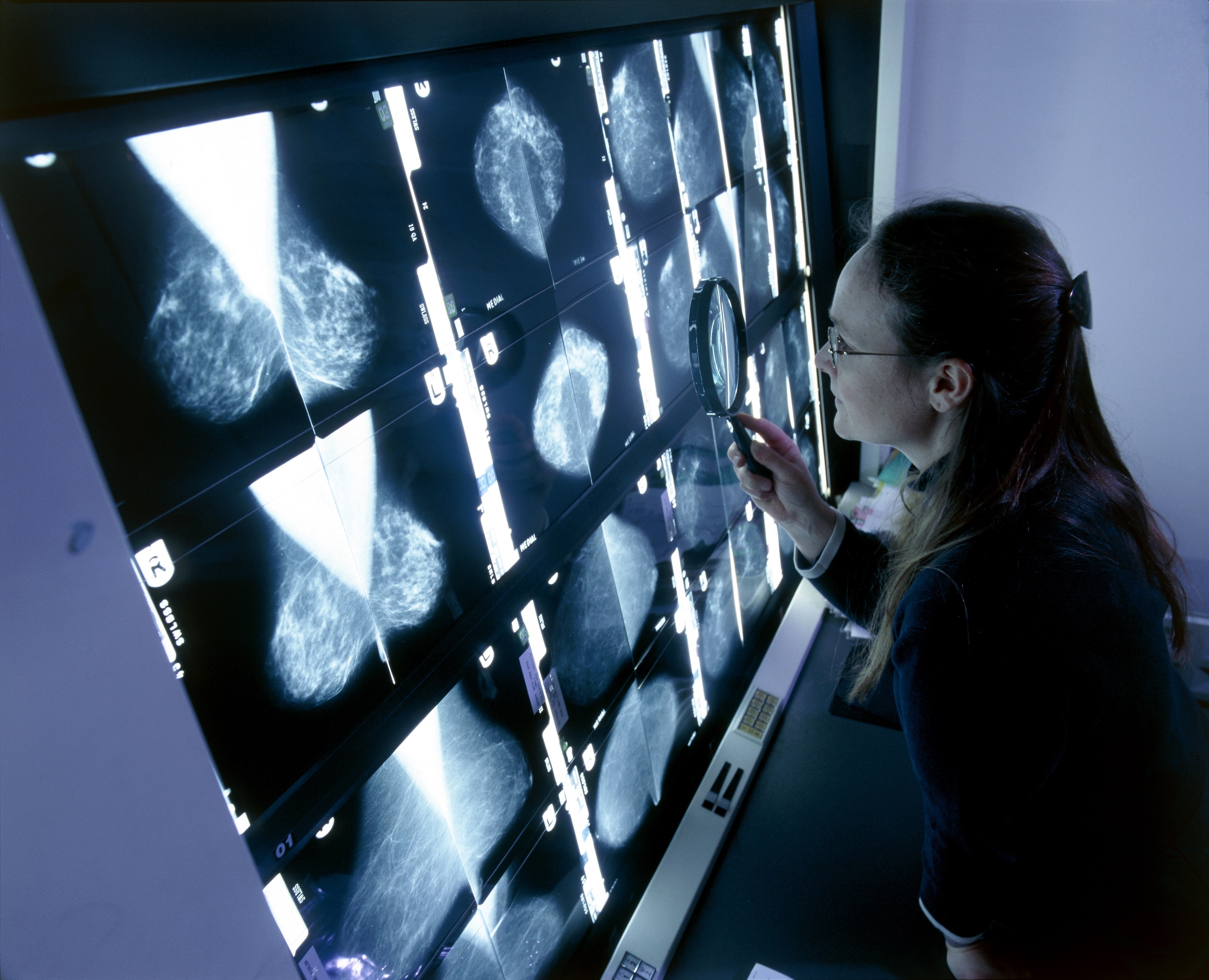

Once the immune system has been overridden, it’s traditionally been the job of conventional—and invasive—protocols to do that work of fighting cancer instead. And once you’ve experienced cancer firsthand, it’s generally been understood that you will live forever with the awareness that it’s always lurking around the fringes of your future, waiting to pop up on the next set of scans. There’s always been another shoe that could drop, another chance the signal could get scrambled again.

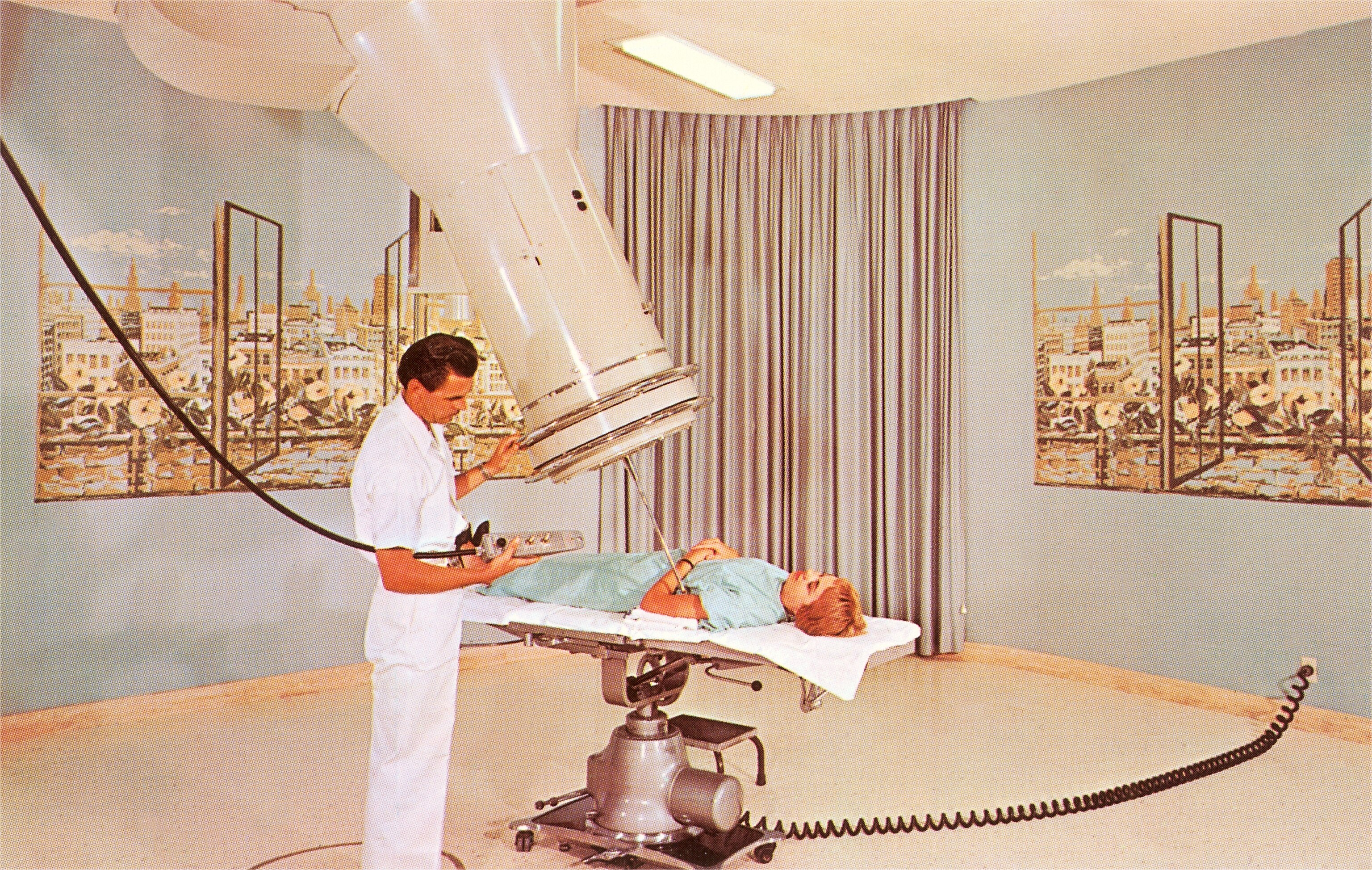

For generations, treatment barely progressed beyond surgery, radiation, and chemo—the holy trinity known as slash, burn, and poison. For many patients, these treatments are highly effective. But because cancer invades on a cellular level, it can be an extraordinary challenge to remove it definitively—and blasting away cancer frequently comes at the expense of the healthy parts of the body too. Surgery cuts around wide margins of the cancer’s surrounding terrain. Chemo kills dividing normal cells as well as cancerous ones.

The toll both the disease and its treatment extract can be profound. Writing in 1957, Australian virologist Macfarlane Burnet concluded that “there is little ground for optimism in cancer,” but added that while at the time “anti-cancer drugs are also carcinogens. A slightly more hopeful approach, which is, however, so dependent on the body’s own resources that it has never been seriously propounded, is an immunological one.”

When President Richard Nixon signed the National Cancer Act of 1971, it was the beginning of a new era in looking at how cancer behaves—and exploring new ways of treating it. Recalling it now, Dr. James Allison, professor and chair of immunology and executive director of the immunotherapy platform at MD Anderson Cancer Center, says, “The best advisers in the field said, ‘We don’t know much but to throw chemo and radiation and surgery at cancer.’ I think what subsequently came out of that work was an amazing amount of detailed information about normal cell growth regulation and how it goes awry in cancer. It’s really magnificent.”

Nearly 40 years later, in 2009, the Obama administration launched a similar initiative, vowing a broad allocation of funds toward medical research across a wide spectrum, including one billion dollars for “research into the genetic causes of cancer and potential targeted treatments.”

Yet even now, the default protocols for patient treatment are still often limited to the familiar trio: surgery, radiation, and chemo. And although overall cancer incidence and death rates have declined since what became known as the 1970s War on Cancer, progress has been slow and success has been erratic.

Can cancer be cured?

One of the other great challenges for researchers has been that cancer has an exasperatingly bountiful array of manifestations. There are more than 100 different kinds of cancer that affect humans. There are cancers of the blood and bones and organs. Cancer is many, many things, though “sneaky” and “unpredictable” tend to be among the universal traits.

A big breakthrough for one form of it doesn’t automatically mean a hopeful “cure” for any other types. Your neuroblastoma isn’t someone else’s breast cancer. The phrase “breast cancer” itself can mean different things to a person with the BRCA2 gene mutation and one without it. And because of individual circumstances and cell mutations, my melanoma isn’t your melanoma.

That’s why there will likely never be a cure for cancer. And I say that as someone who has, for all intents and purposes, been cured. Cancer is not a single disease, and it almost certainly can’t ever be addressed with a single magical potion. It has to be approached with a variety of protocols. So when well-meaning people—or, more infuriatingly, certain cancer organizations that ought to know better—talk about finding “the cure” for “this disease,” it’s a good bet that they are talking a lot of nonsense.

The path of medical research progress is not leading to one solution for everything. But as science moves forward with increasing sophistication and depth, there are going to be more and more patients fortunate enough to obtain a specific treatment—or combination of treatments—that seems to eradicate their cancers.

Even then, though, there will probably always continue to be people for whom those same treatments simply don’t work. We aren’t built on assembly lines. Our bodies are unique. Our cancers are too.