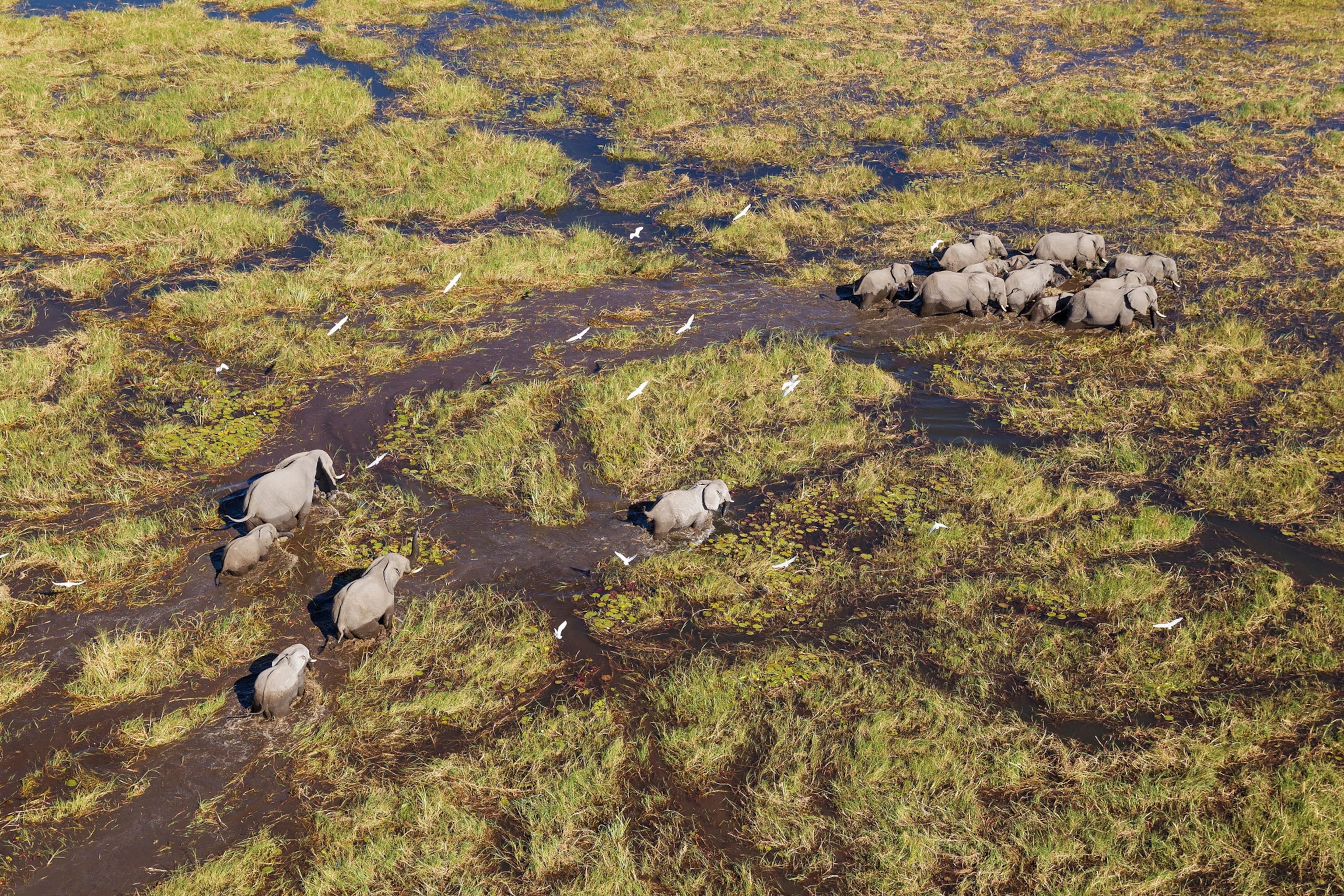

When oil drilling meets threatened wildlife

By Rachael Bale, ANIMALS Executive Editor

It’s home to endangered wild dogs, lions, leopards, giraffes, pangolins, and one of Africa’s biggest concentrations of elephants. Nestled among the scrub are hundreds of species of birds, reptiles, and amphibians. The Okavango region (pictured above), in northwest Botswana and northeast Namibia, is spectacularly biodiverse, and the Okavango Delta itself is a UNESCO World Heritage site, a landscape of “exceptional and rare beauty” and an “outstanding example of the complexity, inter-dependence and interplay of climatic, geo-morphological, hydrological, and biological processes,” UNESCO says.

“Clean water: That is the oil and the gold,” wrote National Geographic’s David Quammen in a 2017 story documenting the region.

Except ... there is oil. And gas. Probably. As much as 31 billion barrels, one company believes. On Wednesday, Laurel Neme and Jeffrey Barbee reported that a company called ReconAfrica has licensed more than 13,600 square miles in the Okavango region—just west and north of the delta—to explore a massive geological formation. One industry media source called it possibly “the largest oil play of the decade.” Neme and Barbee dug into ReconAfrica’s investor presentations, technical reports, and public statements, and they found that the company’s plans—if the test wells prove promising—would likely include drilling hundreds of wells, some of which could involve fracking.

This has conservationists and local communities worried. Fracking requires large amounts of water and has the potential to pollute or divert waterways away from the people and animals that rely on them. It can poison food chains and degrade habitats. Oil extraction and transportation cuts across animals’ migration paths, and new roads can facilitate poaching. The noise and dust and commotion is enough to scare off some animals and change the behavior of others. In highly interconnected environments, the ripple effects could be magnified.

A ReconAfrica spokesperson told Neme and Barbee that the company “will ensure that there is no environmental impact” from the wells—which is hard to verify because the environmental impact assessment and management plans provided to Nat Geo addressing the topic were flawed and incomplete, according to independent experts we spoke to.

The oil exploration plan has received scant media attention, and some local communities and conservationists National Geographic contacted either knew little about it or had never heard of it. We’ll continue to follow the story.

Do you get this newsletter daily? If not, sign up here or forward to a friend.

Today in a minute

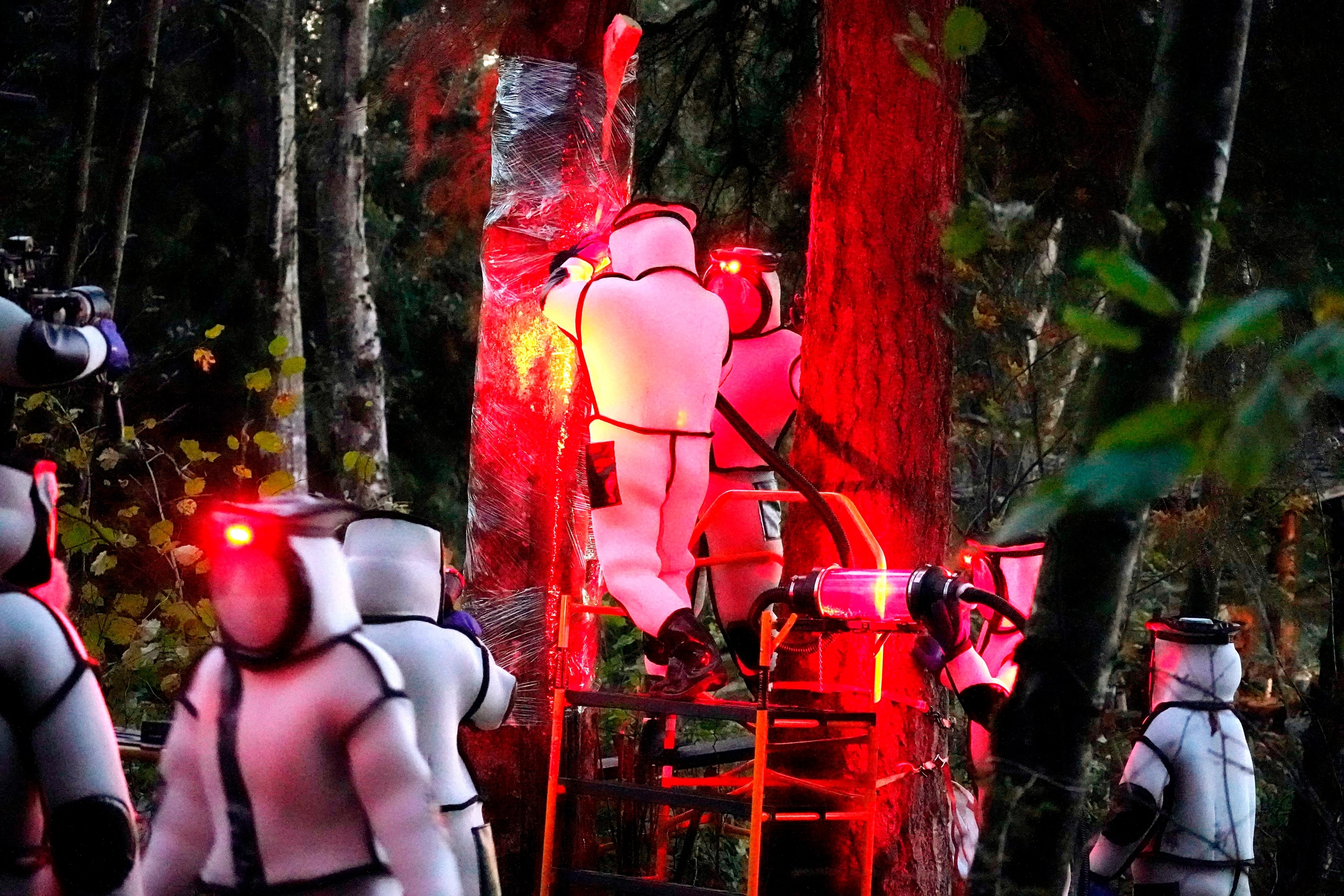

Murder hornets: One nest of Asian giant hornets has been discovered, and officials in Washington State are searching for more. Last Saturday, authorities suited up for the pre-dawn destruction of the nest (pictured above) in protective gear that made them look like Star Wars stormtroopers. With good reason, Nat Geo’s Douglas Main reports. The hornets “protect the queen at all costs,” Doug tells me. Tracking and destroying nests are key to keeping the invasive species—the world's largest wasps—from becoming established in the Pacific Northwest—and destroying honeybees.

Hurricane Zeta: The fast-moving storm left more than two million customers without power in hurricane-weary Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama today as it moved northeast through Georgia. The speed of the storm prevented the scale of flood surges seen in previous storms, the New York Times reports. Zeta was the fifth named storm to hit Louisiana this year and the 27th so far in the Atlantic season, which still has a month to go.

Saving nature to stop pandemics: Deforestation pushes more animals from their habitats and toward people, facilitating the spread of zoonotic diseases. A new UN report, out today, calls for the preservation of plant and animal species to protect humans from the deaths and disruptions of diseases such as COVID-19, Nat Geo’s Sarah Gibbens reports.

From rescue dog to ‘author’: Blind, deaf, and pink, Piglet was one of the most anxious and traumatized puppies her new owner, a veterinarian, had ever met. After patient work, Piglet and Melissa Shapiro didn’t need visual or auditory cues to communicate. Shapiro put photographs of her pet onto Facebook and Instagram to show that profoundly disabled dogs can teach their owners about love and empathy, too, People magazine reports. That led to PIGLET: The Unexpected Story of a Deaf, Blind, Pink Puppy and His Family, to be published next August.

Your Instagram photo of the day

Aerosolized mist: When photographing in the field, Daisy Gilardini quite often looks for her background first, then the foreground. “While visiting a Chilean research station during a recent trip to Antarctica, I noticed the contrast of the gentoo penguin’s breath against the black huts,” Gilardini says. “I waited until one of the penguins started vocalizing to capture this unusual portrait.”

Related: How gentoo penguins communicate with each other underwater

The big takeaway

Saving sharks: The desire for a traditional Asian delicacy—shark fin soup—is behind much of the killing of more than 70 million sharks a year. But a new study points to an easier way to control the carnage. Many of the sharks fished for their fins come from coastal waters—not open seas, as previously thought—and that closer-to-shore habitat is in territorial waters of only a few countries, David Shiffman reports. “That’s potentially good news, because what happens in [territorial waters] is within somebody’s control,” says Kyle Van Houtan, chief scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. “It’s the sole responsibility of that one country.” Countries agree certain shark species should be more tightly controlled; the rub, as always, is the political will to enforce it. (Pictured above, a dried shark fin an a warehouse in Indonesia.)

In a few words

And the things, all the resources I have, they will disappear one day. I mean, I won't be this person for a long time. Soon people will lose interest in me and I won't be so-called “famous” anymore. And then I will have to do something else. So I'm trying to, as long as I have this platform, use it.Greta Thunberg, Pushing to save a threatened planet in a ’post-truth’ world

Did a friend forward this to you?

Come back tomorrow for Whitney Johnson on the latest in photography news. If you’re not a subscriber, sign up here to also get Debra Adams Simmons on history, George Stone on travel, and Victoria Jaggard on science.

The last glimpse

How do animals decide who will lead? These chimpanzees, seen in Uganda, may have an alpha male who uses a gentle approach to build coalitions, or a leader with an iron fist. Other animals take age into account when choosing leaders. For African elephants, the leader is usually the oldest female in a herd. Spotted hyenas choose leaders by sex or by lineage, much as rulers ascend in a monarchy. Sometimes, as in some human elections, appearances play an outsized role. “Stickleback fish simply follow the best-looking of the bunch,” Brian Handwerk writes.