Into the Depths: The other Underground Railroad

"Until there were miles of water between us and our enemies, we were filled with constant apprehensions that the constables would come on board. Neither could I feel quite at ease with the captain and his men ... We were so completely in their power, that if they were bad men, our situation would be dreadful."

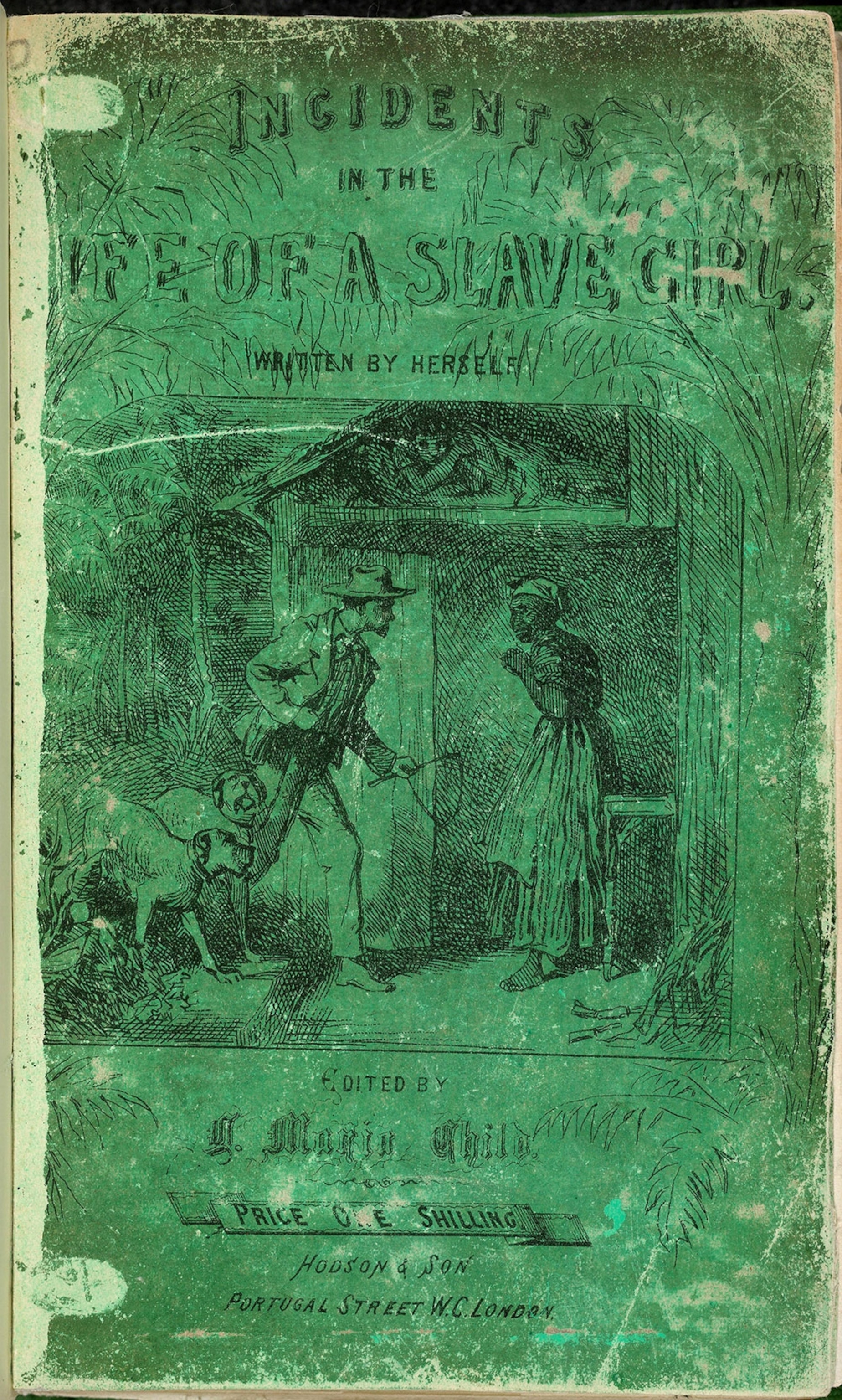

—Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Into the Depths, Episode 6

By Rachel Jones, National Geographic contributor

I'd be willing to bet that 3 out of any 5 people you'd ask would know who Harriet Tubman was and could explain her link to the Underground Railroad.

Now, I'm a smart woman. I'm a Black woman. Some might even call me a "race woman," generally defined as someone who strongly advocates for the rights of and equity for Black people. So when I was asked to write about Harriet Jacobs (seen above in 1894) and the Maritime Underground Railroad, I paused for a minute. It felt like the email request had fallen out of a wormhole in an alternate universe and onto my laptop.

I thought I was being punked.

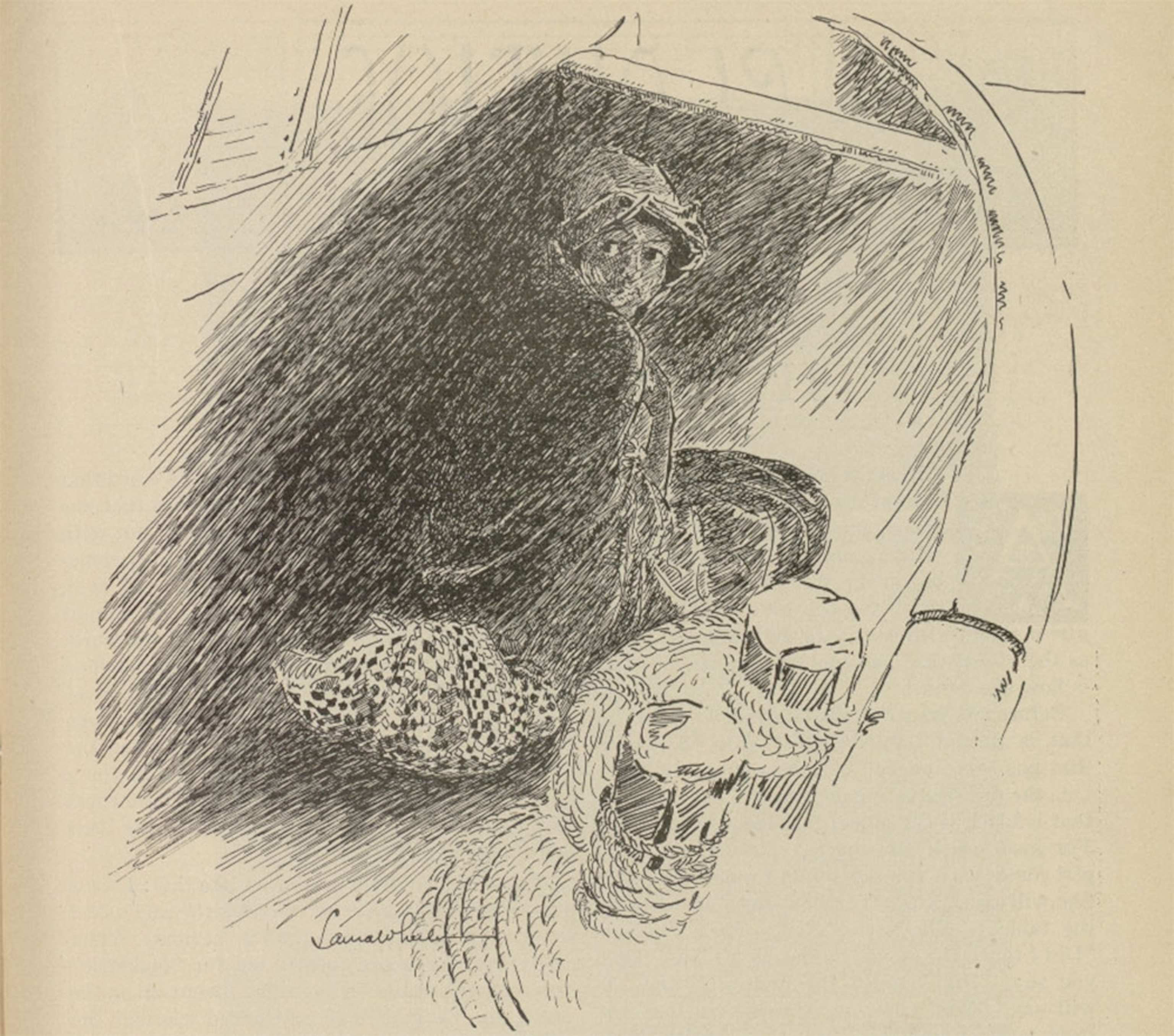

A Google search later, I was stunned. Though I've attended more Black History Month events than I could list, I had never heard of Harriet Jacobs, born in February of 1813 in Edenton, N.C. She was repeatedly sexually assaulted by her owner, who threatened to sell her children if she didn't submit. At one point, she hid for nine years in a 9-by-7-by-3-foot crawlspace, boring holes in the wooden planks to get fresh air. Eventually, with the help of anti-slavery activists of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, Jacobs was able to escape through the Maritime Underground Railroad, a network of people who helped slaves travel aboard the thousands of ships that sailed up and down the Atlantic coast.

These African American men and women sought out sympathetic vessel captains and crew, impersonated free Black passengers, did what they had to do to reach Northern states and Canada. They were so successful that Southern lawmakers created legislation called the Negro Seamen Acts in 1822 to try to control the movement of Black people on the nation's coastlines and aboard vessels.

Harriet Jacobs died in 1897 in Washington, D.C., having become a well-known abolitionist and author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which raised awareness of the sexual exploitation of enslaved women. And as I vow to learn more about her life, I can't help but consider just how many other unsung Harriets are out there, waiting for their stories to be told.

Rachel Jones is Director of Journalism Initiatives for the National Press Foundation and a frequent contributor to National Geographic.

Ten days after we left land, we were approaching Philadelphia. I was on deck as soon as the day dawned ... to see the sunrise, for the first time in our lives, on free soil. We watched the reddening sky and saw the great orb come up slowly out of the water.Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Into the Depths, Episode 6

DID YOU KNOW?

This year, cities across the United States are marking the 200th anniversary of Harriet Tubman's birth. The abolitionist and humanitarian wore many hats, including nurse, scout, and spy for the Union Army. She was also the first woman in the U.S. to lead an armed military raid.

READ MORE: Discovering Harriet Tubman's true story on Maryland's Eastern Shore

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

Learn more about the people, places, and ships mentioned in the podcast Into the Depths in the National Geographic Society's Resource Library for educators, students, and lifelong learners. And visit the links provided here for more stories about the men and women who survived the slave trade.

• Henry Brown spent the first 35 years of his life enslaved by a Virginia plantation owner. In 1849, after discovering his wife and three children had been sold, he folded himself into a 3-foot-by-2-foot wooden crate—and mailed himself to freedom. Read his story here.

• Sojourner Truth, the legendary abolitionist and women's rights activist, was also one of the first Black women in U.S. history to win a legal case against a white man—for selling her son. And, ironically, although she is known primarily for her famous "Ain't I a Woman?" speech, she more than likely never actually used that phrase. Learn more about her life and her legacy.

• Before he escaped to freedom and became one of America's great abolitionists, writers, orators, and icons, Frederick Douglass was in bondage, at the plantation of Captain Thomas Auld. The two men would meet face to face again, many decades later, when Auld was near death. Read about their encounter.