Can we go to space while still protecting Earth?

This article is an adaptation of our weekly Science newsletter that was originally sent out on April 21, 2021. Want this in your inbox? Sign up here.

By Victoria Jaggard, SCIENCE executive editor

If the weather cooperates and all the technology checks out, four astronauts will lift off Friday morning for the International Space Station. Since the ISS has had people on board continuously for the past 20 years, this feat might seem routine. But if everything goes to plan, these astronauts will make history by becoming the first humans propelled into space by an entirely reused rocket booster.

As a child of the space shuttle era, I grew up with the notion that making space travel routine requires reusability. That idea didn’t exactly work out for the shuttle fleet, which was partially reusable but never in a way that made it any cheaper. Facing both budget and safety concerns, the shuttle program was retired in 2011. A mere four years later, though, SpaceX got NASA back in the reusability game when it landed a rocket booster on Earth after a successful orbital launch. SpaceX has so far seen 40 booster landings out of 47 attempts, and the company has reused previously flown boosters multiple times since 2017. The trick being, all those flights involved cargo, not crew.

Now, SpaceX is gearing up for its Crew-2 mission, which will see astronauts Shane Kimbrough, Megan McArthur, Akihiko Hoshide, and Thomas Pesquet launched into space by the same rocket booster that sent four of their colleagues to the ISS during the Crew-1 mission in November. (Pictured above, SpaceX Crew-2’s Kimbrough, McArthur, Hoshide, and Pesquet, inside a mockup of the vehicle at the training facility in California. Falcon Heavy, pictured below, the world's most powerful operational rocket, successfully launched its first commercial payload into space in 2019. Three Falcon 9 rocket cores, together with 27 Merlin engines, generate the equivalent thrust of approximately 18,747 aircraft.)

Plenty of ink has been spilled over the environmental impacts of space travel. It’s costly, it can be wasteful, and debate swirls over the potential carbon emissions. But to balance the scales, space travel arguably helped launch the environmental movement by clearly showing us the fragility of our home planet, and satellite data plays a huge role in our understanding of modern climate change. Now, right around Earth Day 2021, human spaceflight is set to take the values of reducing, reusing, and recycling to whole new heights.

Do you get this daily? If not, sign up here or forward to a friend.

TODAY IN A MINUTE

The new normal? Millions breathed a collective sigh of relief after getting that first or second jab of the COVID vaccine in the arm. But scientists say they aren’t sure just how long that protection will last, especially as the virus continues to mutate. The new normal could mean routine inoculation, or periodic booster shots, against COVID-19, Jillian Kramer writes for Nat Geo. Thankfully, data increasingly show that fully vaccinated people are much less likely to transmit the virus.

Citizen scientists: The pandemic, which has left many of us with time on our hands, has inspired a bunch of budding scientists. Millions of global amateurs are helping researchers on everything from watching birds and plants to tracking COVID-19. That crowdsourcing has the added bonus of creating a community for the volunteers, Vox reports.

Her passion has saved many lives: Kati Kariko’s ideas have been unconventional—and haven't gotten grants. For decades, the scientist never made more than $60,000 a year. Her passion has been the lab—and messenger RNA cells, the New York Times reports. Only now, at 66, is Kariko getting wider attention: for laying the foundation for the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID vaccines.

Nuclear fallout: American honey still carries traces of a radioactive element from atom-bomb testing during the Cold War, according to a new study. The levels of contamination found in the honey aren’t harmful to humans but the research raises questions about how cesium has impacted bees and highlights the long-term effects of the fallout, Justin Richardson, a biogeochemist at the University of Massachusetts tells Science magazine. After the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, scientists discovered that radiation could threaten the reproduction of bumblebee colonies.

INSTAGRAM PHOTO OF THE DAY

Thin ice: The Rhône glacier, a tourist attraction in the Alps, is tucked inside a cave in Switzerland. To slow the glacier melt, the Carlen family, who has managed the cave since 1988, came up with the idea of covering their part of the glacier with fleece blankets to reflect the sunlight. Despite the efforts covering the ice cave—it might only be around for a couple more years as the glacier is melting too fast. Nat Geo Explorer Ciril Jazbec took this image on assignment.

Seeing Earth: 50 dramatic, can’t-miss photographs of our world

THE NIGHT SKIES

Lyrid meteor shower peak: Sky-watchers are gearing up. Thursday night to Friday morning is the apex of the annual Lyrid meteor shower. From a dark location, preferably away from light pollution from cities, expect to see 15 to 20 shooting stars zip across the sky. There is a chance of extra bursts of activity; twice in the past century rates rose to as high as 100 an hour, and ancient Chinese astronomers once noted the Lyrids sent meteors “falling like rain.” One tip: Because of this year’s bright waxing gibbous moon, the better shot at shooting stars may come in the predawn hours of Friday. — Andrew Fazekas

THE BIG TAKEAWAY

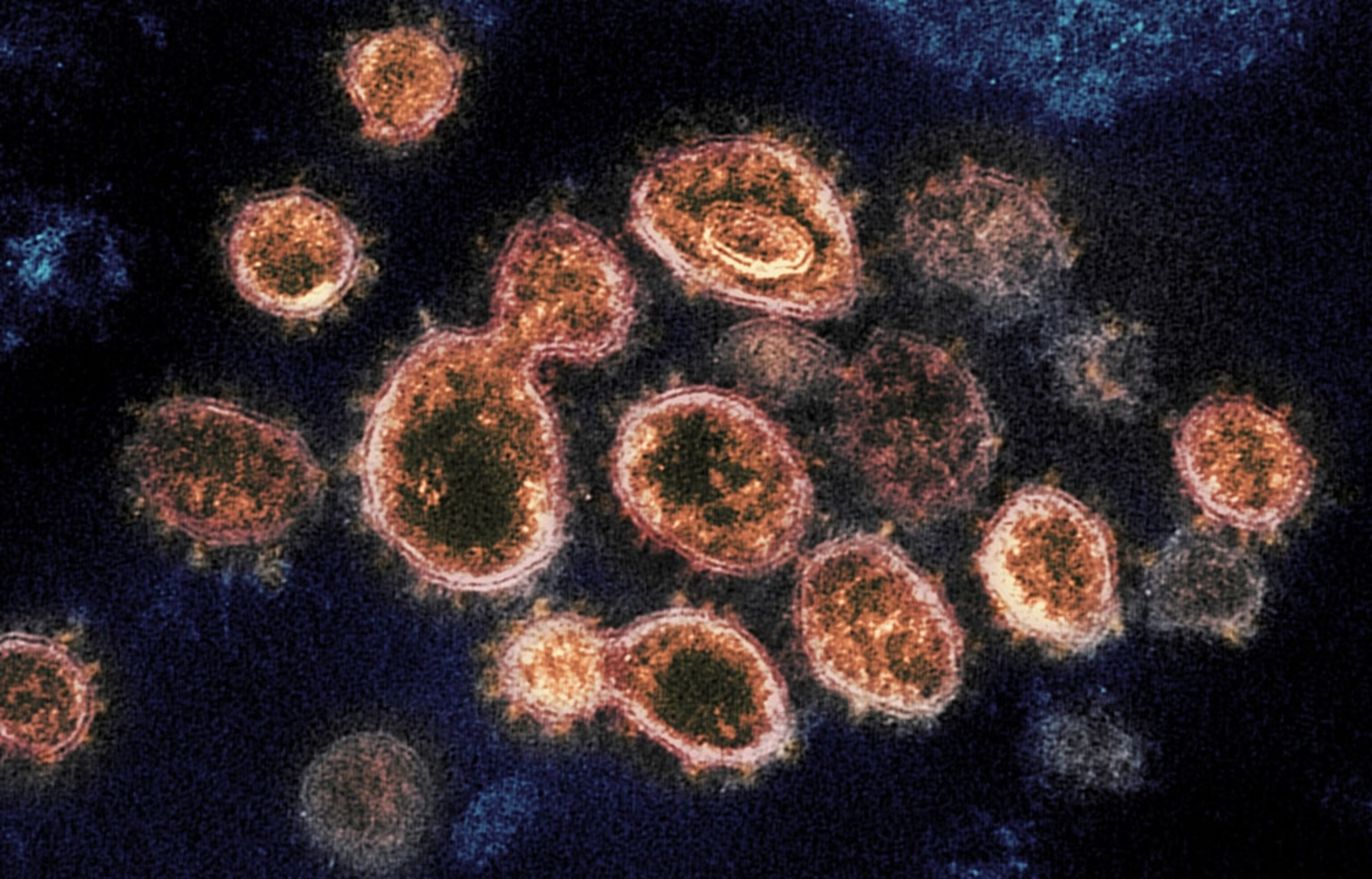

What’s in a name? B..1.1.7, P.1,501Y.V2. Those jumbles of numbers and letters might be easy for scientists to track, but not so much for the average Joe trying to keep up with virus variants. “Who wants to keep saying 501Y.V2?” Salim Abdool Karim, an epidemiologist who helped name the variant also known as B.1.351 and 20H/501Y.V2 told Nat Geo. “501Y.V2 is such a mouthful to say. It’s a terrible name. You wouldn’t want to call your child 501Y.V2.” The naming system might be up for a change. The World Health Organization has convened a committee to replace names that are confusing while avoiding geographic monikers, like the U.K. variant, which can be misleading and even inaccurate. (Pictured above, this electron microscope image, captured and colorized at NIAID’s Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Montana, shows SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, isolated from a patient. The spikes on the outer edge of the virus particles give coronaviruses their name, “crown-like”.)

IN A FEW WORDS

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

Arundhati Roy, Author, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, From: ‘The pandemic is a portal’

DID A FRIEND FORWARD THIS NEWSLETTER?

Come back tomorrow for Rachael Bale on the latest in animal news. If you’re not a subscriber, sign up here to also get Whitney Johnson on photography, Debra Adams Simmons on history, George Stone on travel, and Robert Kunzig on the environment.

THE LAST GLIMPSE

How many?? Billions of Tyrannosaurus rex lived in North America, over a span of 2 million to 3 million years, paleontologists have calculated. That means, that if you were alive during their time, a T.rex would probably have been within 15 miles of you, if not much closer, according to the latest dino research. “It’s really exciting that someone’s trying to … use everything we know about T. rex to try and figure out population dynamics,” paleontologist Holly Woodward told Nat Geo.

This newsletter has been curated and edited by David Beard and Monica Williams, with photo selections by Jen Tse. Have an idea or a link to share? We'd love to hear from you at david.beard@natgeo.com. Thanks for reading, and have a good week ahead.