This article is an adaptation of our weekly Science newsletter that was originally sent out on February 10, 2021. Want this in your inbox? Sign up here.

By Robert Kunzig, ENVIRONMENT executive editor

What will future archaeologists think of us? For example, when they radar-scan the prairie in southern Alberta and discover a line of buried pipe, three feet wide and tens of miles long, that begins and ends—nowhere?

The Keystone XL pipeline is dead, for now. On Inauguration Day, President Joe Biden revoked the permit granted by his predecessor.

But as journalist and Nat Geo Explorer Alec Jacobson writes this week, even if 830,000 barrels of oil a day never flow down 1,200 miles of pipe, Keystone will cast a long shadow over the industry, the people in the region, and the land itself. The cross-country chain of perpetual easements, the pump stations and the man camps, and about 90 miles of assembled pipeline, mostly in Alberta—all that will remain. (Pictured above, unused pipe intended for Keystone, stored in a field near the Montana-North Dakota border.)

Keystone is just one project among many; more than 130,000 miles of oil or gas pipelines are now under construction or planned, according to Global Energy Monitor. Those projects face one of two fates: Either they’ll lock us in to more climate-warming carbon emissions, as much as 170 gigatons worth, or they’ll become $1 trillion worth of “stranded assets,” once governments and markets finally decide that the emissions really must stop.

Long before Keystone XL, I flew over the oil sands mines of northern Alberta for National Geographic. Looking down at the flames flaring from the refineries and the sun glinting off the tailings ponds, at the stupendous shovels scraping away at the bitumen seam in open pits, at monster trucks kicking up banks of dust that drifted out over the boreal forest, I was horrified, sure. But mostly I was amazed. There was a terrible beauty to it, to the effort we put into digging energy from the Earth, energy that has made a globe-spanning civilization possible.

And maybe those future archaeologists working in Alberta will be amazed, too—in a good way. Maybe that pipeline to nowhere won’t just make us look silly. Instead it might support a flattering conclusion about us: that we realized when we had to change fundamentally, and did so just in time.

Note: Our Keystone reporting was supported in part by the National Geographic Society’s COVID-19 Emergency Fund for Journalists.

Do you get this newsletter daily? If not, sign up here or forward to a friend.

TODAY IN A MINUTE

Guilty of what? In what has been billed as an immense victory for climate activists, a Paris court has found the French government guilty of of failing to address the climate crisis and not keeping its promises to tackle greenhouse gas emissions. The court ruled that compensation for “ecological damage” was admissible, and awarded a symbolic euro to each of the four environmental groups that brought the lawsuit, the Guardian reports.

A threat to us? The world’s most commonly used family of pesticides, developed in the 1990s as a “safer” alternative, may be harming mammals, too. Bees, essential for crop pollination, have been especially hard hit by neonics—and the EU has banned the outdoor use of three popular types. Exposure to neonics “reduces sperm production and increases abortions and skeletal abnormalities in rats; suppresses the immune response of mice and the sexual function of Italian male wall lizards; impairs mobility of tadpoles; increases miscarriage and premature birth in rabbits; and reduces survival of red-legged partridges, both adults and chicks,” Elizabeth Royte writes for Nat Geo.

Today I learned: Planting clover and other winter crops can suck up more carbon gases and help the planet. Farmers traditionally planted winter crops to feed microbes and improve the soil’s health. “But just as importantly, they will pull down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in the ground,” the Washington Post reports. How much? One winter crop-planting Maryland farmer has sequestered more than 8,000 tons of carbon in the soil over the past few years.

A vaccine while pregnant? The CDC leaves it up to the patient. The WHO counsels against it unless you have high COVID-19 risk factors. And there’s little safety data showing how the new Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines work for pregnant people. To help them decide whether to vaccinate, Nat Geo’s Amy McKeever writes, experts suggest balancing what we do know about these two vaccines—including that they do not contain live virus and cannot cause infections—against the increased risk pregnant people face from contracting COVID-19.

R.I.P. Arianna Wright Rosenbluth: She helped create one of the most important algorithms of all time, a method used today in everything from social sciences to understanding COVID-19’s spread. At 21, she was only the fifth woman given a Harvard doctorate in physics in 76 years. Three years later, Rosenbluth, a championship fencer, was in Los Alamos, verifying analytic calculations for the first full-scale test of a thermonuclear bomb. But by her mid-20s, she had left the field and rarely talked about her titanic accomplishments. Rosenbluth died of complications of COVID-19, the New York Times reported. She was 93.

INSTAGRAM PHOTO OF THE DAY

Studying Earth from the top of the world: At an Arctic research station in Svalbard, Norway, scientists Rita Traversi and Mirko Severi approach a lab in which chemical and physical aerosol properties are studied. The two are carrying rifles as part of protocols to protect them from marauding bears. Readers, like this image? So do more than 188,000 people who saw it on our main Instagram page.

Brrrr! Welcome to the world’s northernmost science lab

THE NIGHT SKIES

Giant hexagon: With Thursday’s new moon, we will have darker skies that will be perfect to check out the Winter Hexagon rising in the east on early evenings. Start with Sirius, the brightest star visible from Earth. It marks the constellation Canis Major, the great dog. You can easily find this white-colored star by following the line of three stars that form Orion’s belt eastward (left). The second point in the Hexagon is the white star Procyon, which marks the constellation Canis Minor. Point three includes the side-by-side stars Castor and Pollux, representing the heads of the Gemini twins. Next is Capella, shining with a hint of golden-yellow in the constellation Auriga, the charioteer. Following Orion’s belt up and westward (right) leads us to our fifth point, Aldeberan, a glittering orange-yellow dot that marks the eye of Taurus, the bull. The tour closes with the brilliant blue-white star Rigel in Orion. — Andrew Fazekas

See: How ancient astronomy mixed science with mythology

OVERHEARD AT NAT GEO

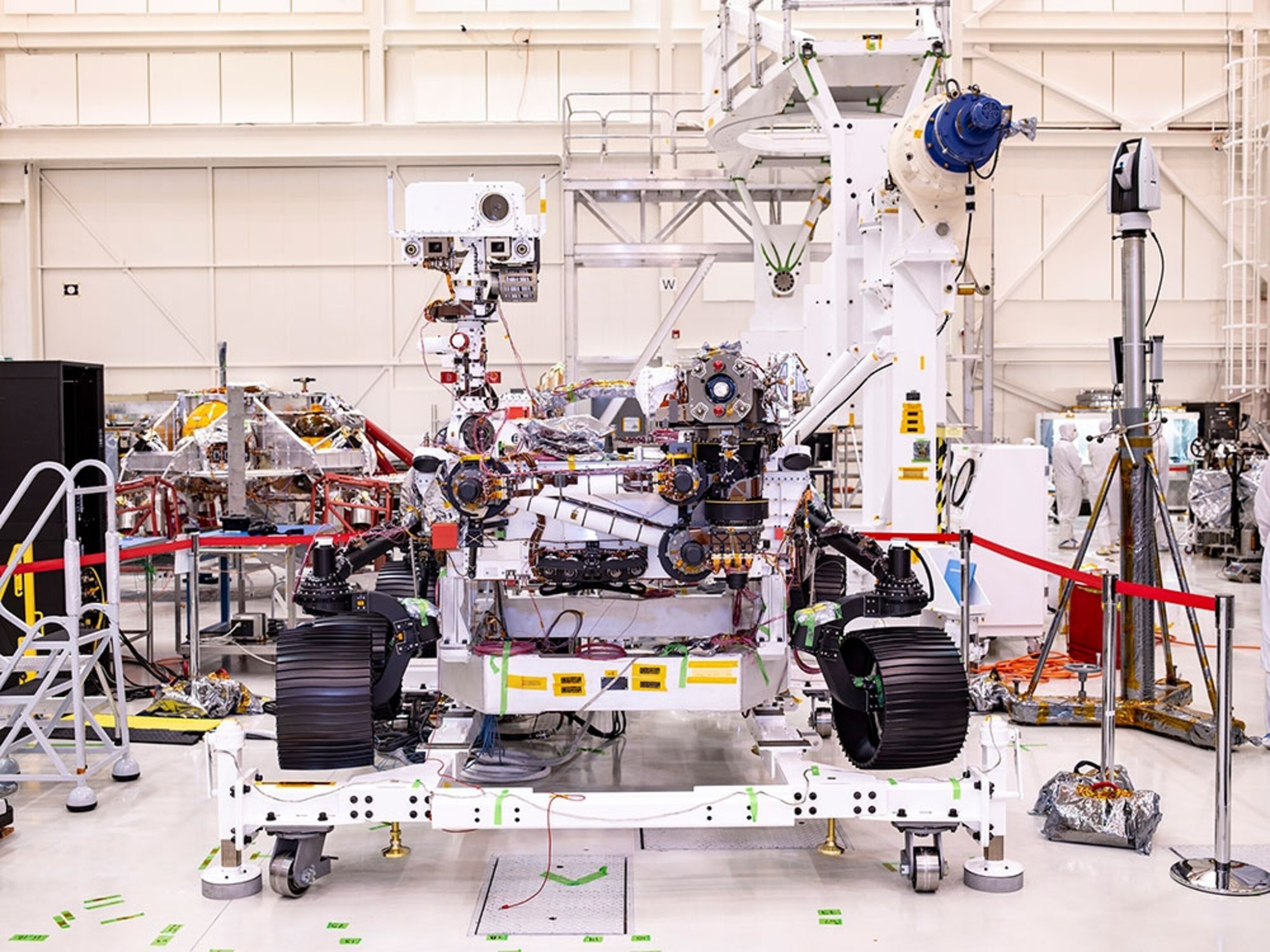

Closeup: As the latest rover heads toward Mars, NASA officials and Nat Geo’s Nadia Drake talk about science’s age-old fascination with the red planet. “It’s just blank enough that we can populate it with our imaginings,” Drake tells our podcast, Overheard. One thing the rover’s principal investigator, Jim Bell, hopes to learn more about is the color of the Martian sky. “It’s been described as pink. It’s been described as salmon. It’s been described as butterscotch. And it changes,” he tells us. “It changes with time of day. It changes from day to day, as dust storms come and go, just like Earth’s sky. On Mars there’s always dust in the atmosphere. The atmosphere is so thin that if there were no dust, the sky would be black, like on the moon.” Hear more! For Nat Geo subscribers, see how NASA’s Perseverance rover will cover Mars.

THE BIG TAKEAWAY

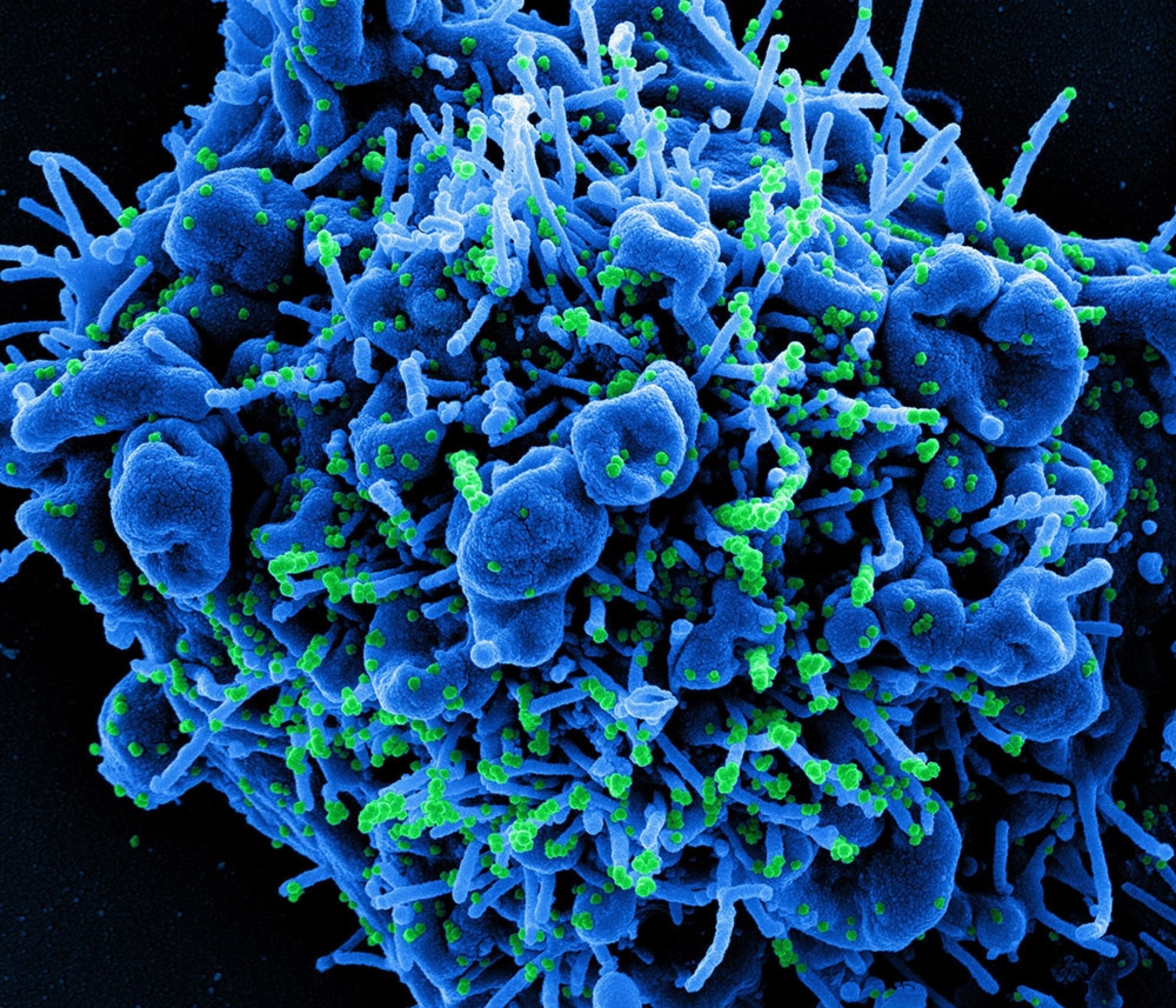

Why is the virus mutating so much? Mutation is a part of life, but the rapid variations of SARS-CoV-2 have taxed scientists seeking to quell the deadly pandemic. “We are creating variants like gangbusters right now because we have so many humans infected with SARS CoV-2,” says Siobain Duffy, an evolutionary biologist at Rutgers. The mutations are like typos in the string of “letters” that make up a strand of DNA or RNA code, Nat Geo’s Maya Wei-Haas writes. Pictured above, a colorized microscope image shows a dying cell (blue) infected with SARS-CoV-2 (green).

IN A FEW WORDS

If we want to control [COVID-19] and get back into normal life, then being able to protect everybody, so we don’t have ongoing transmission in subgroups of the population, is important.

Andrew Ustianowski, Infectious disease specialist, the U.K.’s National Institute for Health Research, From: What are vaccine alternatives for people with compromised immune systems?

DID A FRIEND FORWARD THIS NEWSLETTER?

On Thursday, Rachael Bale covers the latest in animal news. If you’re not a subscriber, sign up here to also get Whitney Johnson on photography, Debra Adams Simmons on history, and George Stone on travel.

THE LAST GLIMPSE

Will drilling put these caves at risk? Over geologic time, chemical processes dissolved rocks inside these caves, giving their prehistoric stalagmites and stalactites pristine information on ancient climate and well-preserved fossils, artifacts, and organisms. They also sit above the country’s largest technically recoverable oil and gas reserves, in the Permian Basin of West Texas and southeastern New Mexico. A Nat Geo investigation finds that drilling may risk contamination of aquifers that supply drinking water to tens of thousands of homeowners. (Pictured above, a scientist admires gypsum "chandeliers" inside the 150-mile-long Lechuguilla Cave.)

This newsletter has been curated and edited by David Beard, with photo selections by Jen Tse. Kimberly Pecoraro and Gretchen Ortega helped produce this. Have an idea or a link? We’d love to hear from you at david.beard@natgeo.com. Thanks for reading, and have a good week ahead.