River's decline cuts water supply to U.S. west

In today's newsletter, ways to conserve water; mining precious metals from plants; the COVID-wildfire connection, and how to keep cities cleaner in the future...

This article is an adaptation of our weekly Planet Possible newsletter that was originally sent out on August 17, 2021. Want this in your inbox? Sign up here.

By Robert Kunzig, ENVIRONMENT Executive Editor

A disaster can be long-expected and still come faster than expected.

People have been forecasting a long-term drying of the West for well over a decade. By this spring, as Alejandra Borunda wrote for us at the time, it was pretty clear that the water level in Lake Mead (pictured above), behind Hoover Dam, would drop below an elevation of 1,075 feet this summer, obliging the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to declare a water shortage on the Colorado River for the first time since the dam was built in the 1930s.

And yet when officials did just that yesterday, on a day when the news was consumed with the sudden collapse of Afghanistan, it still came as a bit of a shock.

Arizona farmers will suffer first, as the state loses nearly a fifth of the water it gets from the Colorado. But Nevada will take a hit too. And if the drought wears on, and Lake Mead continues to drop, cuts are coming to the water supply of other states, including California.

A long-feared reckoning is at hand. The “megadrought” is likely to wear on. "It’s really climate change that pushed this event to be one of the worst in 500 years,” Columbia University climate scientist Ben Cook told Borunda.

People have been forecasting a long-term increase in wildfires in the West for a long time too.

We’ve been watching it happen. Between 1983 and 2001, according to statistics from the National Interagency Fire Center, an average of 3.24 million acres a year burned in the U.S. Between 2002 and 2020, that figure more than doubled, to 7.21 million acres a year.

Drought promotes fire, climate change promotes both. This long hot summer has felt a bit like a doom cycle. Yet the path to limiting climate change is clear, and we’re starting to stumble down it. The path to healthier, less fire-prone forests is clear too: As scientists have been telling us for decades, we need to unlearn the lesson we absorbed from Smokey Bear, that all fire is bad, and allow controlled, prescribed burns back into the woods to clean out the excess fuel—like the Native Americans used to do.

At the same time, as Jennifer Oldham writes for Nat Geo this week, we need to pay more attention to Smokey Bear (pictured above at L.A.’s Griffith Park). The septuagenarian bear’s handlers are working hard to update his messaging for a younger and more diverse audience.

What?

Humans ignite more than 80 percent of all wildfires, Oldham explains, and 97 percent of all fires that threaten homes, in large part because of the American penchant for building homes in the woods. No spark, no wildfire—and with our burning of leaves on windy days, our undoused campfires, and our ill-placed fireworks, we provide most of the sparks.

Sometimes we need to find room in our mind for truths that may sound contradictory. Our problems feel overwhelming, of the kind that only concerted action by governments can solve—Western forests need cleaning, Western water use needs reforming, the whole global energy system needs changing—and yet our actions as individuals still matter.

Maybe, if we can manage not to lose heart, some good changes too will come faster than we expect.

If you want to get this email each week, join us here and invite a friend.

What's being done to conserve water:

— In June, Nevada announced a ban on “non-functionable grass” to conserve water. That term covers nearly a third of current grass in the Las Vegas area—and could reduce the state’s dependence on the Colorado River by 10 percent, EcoWatch reports.

— During the last drought, California eventually required residents to cut water use by 25 percent. They got close, cutting use by 24.5 percent in all, largely by changing what they did outside their homes—including tearing out lawns, installing greywater systems, and putting in irrigation timers.

— Conservation sticks. Before the 2015 California water restrictions, about half of all residential water use was outdoors. California’s residential water usage is still down 16 percent from pre-2012-15 levels, Borunda tells us.

TAKE FIVE

- Air pollution from wildfires heightens danger of COVID vulnerability (Above, a firefighter monitors a fire in Cherry Valley, California)

- Mining zinc, nickel, and cobalt—from plants

- High schoolers say climate report fuels their desire for action. ‘We have so much to lose.’

- A literal return to the earth’: Is human composting the greenest burial?

- Are ‘green banks’ really better for the environment?

PLANET SMART

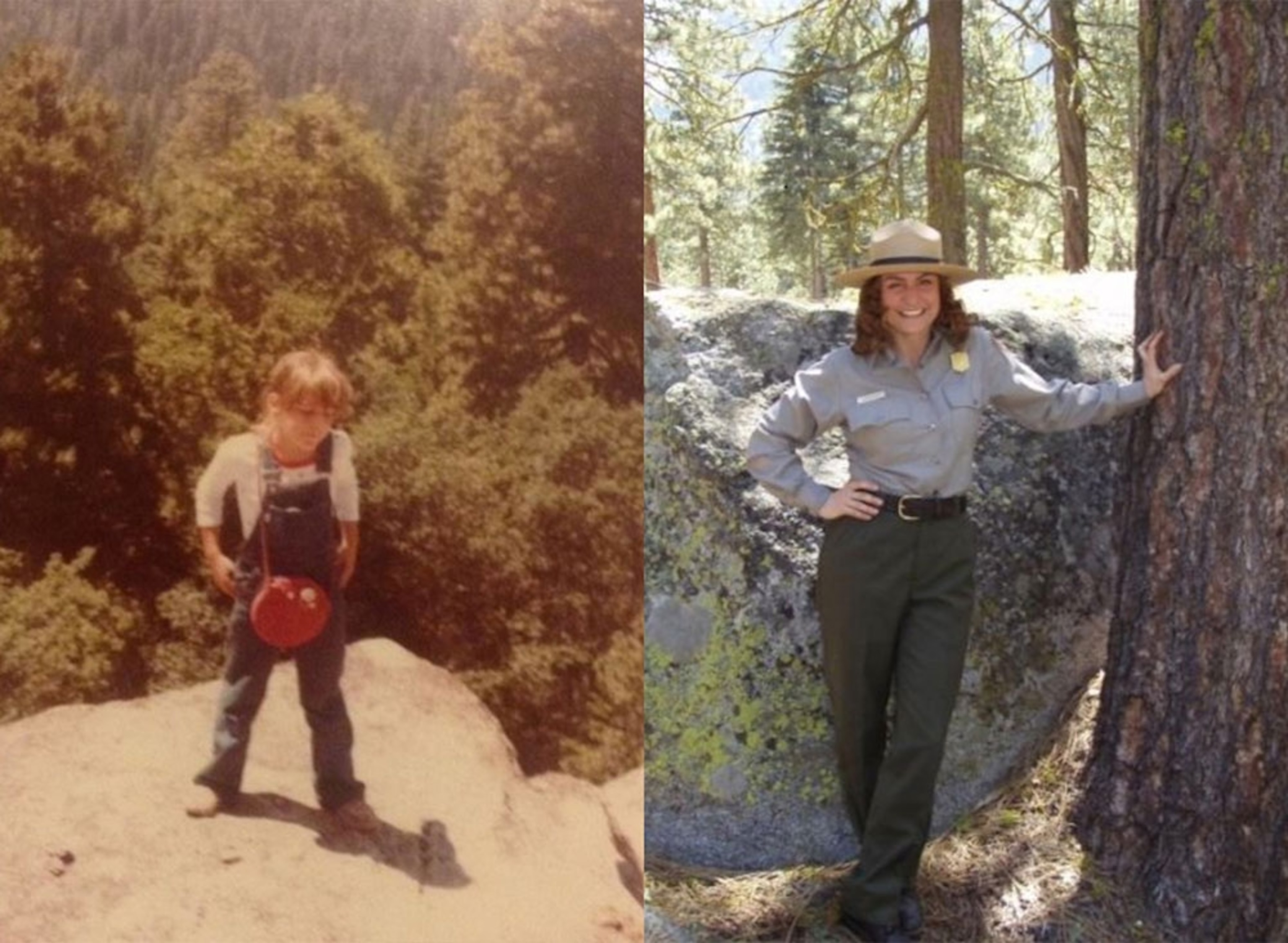

Better together? Wouldn’t it be smarter if a planned national monument were run by the U.S. National Park Service and connect California’s Yosemite and Kings Canyon parks? Proponents say that would allow species—plants and animals—to move easily to and from the current Sierra National Forest as the climate changes. Opponents don’t want to change Bureau of Land Management oversight, which has permitted mining claims, timber sales, grazing leases, and private inholdings, Kurt Repanshek reports. (Above left, national monument proponent Deanna Lynn Wulff as a kid in the southern Sierra Nevada; at right, as a national park ranger in 2008.)

Dig deeper: How the U.S. can triple its protected lands by 2030

ONE MOMENT

Cleaner air: This coal-fired power plant near the Grand Canyon in Arizona is polluting no more. The largest coal plant in the western U.S. for decades, it even made the cover of National Geographic in the 1980s for a story about clean air. When the plant owners decided shutting it at the end of last year would be the most economical decision, it had provided the Navajo Nation and the Hopi Tribe with revenue for over 40 years and had more than 500 employees—90 percent of whom were Navajo. Its closure raises the question of what role cleaner energy can play in replacing plants like the one above—hopefully providing jobs and helping our environment at the same time.

Dig deeper: Why we need to give air pollution the sustained attention it deserves

How to reduce pollution’s toll on your health:

1. Use the air quality index as a guide

2. Consider using air purifiers

3. Replace filters

4. Promote clean, renewable energy

5. Change out your gas stove

Source: Harvard Medical School

IN A FEW WORDS

These semi-apocalyptic scenarios—not just fires, but rising seas, floods, drought, extinction—will become a horrific "normal" unless governments move at breakneck speed to not just reduce but eliminate fossil fuel pollution in our lifetimes.

John Sutter, Nat Geo Explorer and Emmy-nominated director

FAST FORWARD

Cities of the future: We asked experts for ways to make cities more sustainable in the years to come. The ideas are amazing, from green roofs and urban farms to scaled transit and drone commuting. Above, a National Geographic illustration shows the experts’ visions of their city of tomorrow.

Dig deeper: To build the cities of the future, we must get out of our cars

We hope you liked today’s Planet Possible newsletter. This was edited and curated by Monica Williams and David Beard, and photographs were selected by Heather Kim. Have any suggestions for helping the planet or links to such stories? Let us know at david.beard@natgeo.com. Have a good week ahead!

.jpg)