This article is an adaptation of a special edition Photography newsletter that was originally sent out on September 11, 2021. Want this in your inbox? Sign up here.

By Whitney Johnson, Director of Visual and Immersive Experiences

Photographs by Henry Leutwyler

Twenty years have passed, yet it feels like yesterday. I know exactly where I was that morning: in Latin class, seven miles uptown from what would come to be known as Ground Zero.

Photographer Henry Leutwyler was nearby, too. Much closer. He watched the first World Trade Center tower fall from his rooftop at Broadway and Bleecker in Lower Manhattan. His direct connection to this moment in history, combined with his ability to imbue simple objects with emotion, made him the ideal photographer, years later, for a unique project.

Over the course of two weeks, with unprecedented access to the 9/11 Memorial & Museum, he combed through hundreds of dusty boxes in the archive, each with close to 20 objects inside. Henry made thousands of photographs. They carry a power and dignity of their own—and some are featured in this story in September’s issue of National Geographic.

While working, Henry’s team wore respirators and gloves for their own safety, and out of respect for the objects being handled. “You have to be psychologically ready to start a project like this one,” he says.

The smallest, most commonplace objects plucked raw emotion. His assistant took one look at a pair of crushed headphones and broke down in tears. (Pictured above, the helmet of slain firefighter Joe Hunter, recovered in the rubble of the World Trade Center months later; below, the work pants that volunteer EMT Greg Gully encased in plastic after his 9/11 shift at the scene, with a note saying “the ash is the remains of those that died, God Bless Them!”)

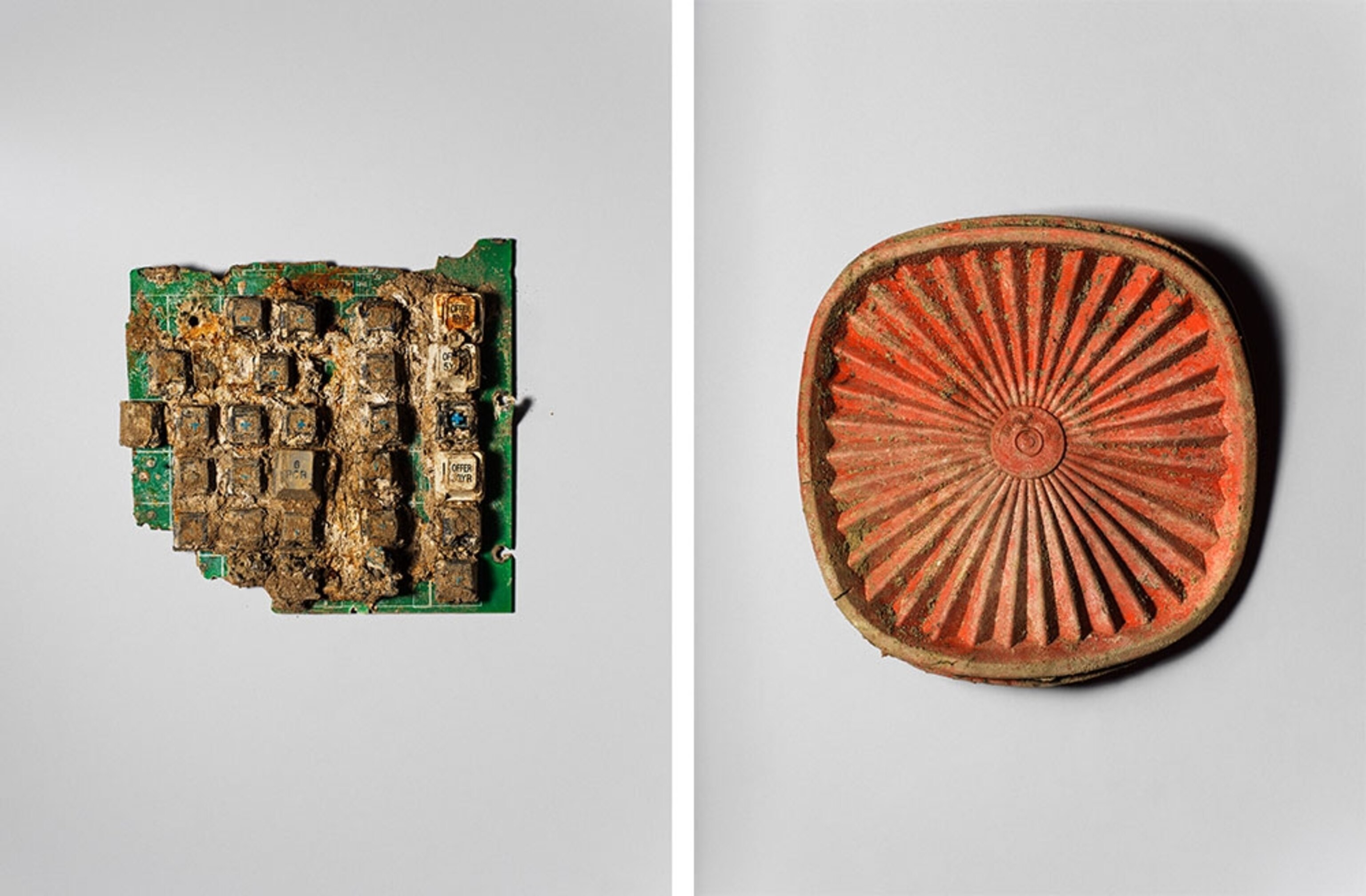

Henry has drawn inspiration from Irving Penn—master portraitist, fashion, and still life photographer, who once said: “A still life is a representation of people … Each still life object has got to tell as much of a human story as if you looked right into a human being’s eyes.” (Pictured below, at left a dirt-encrusted computer keyboard; at right, a lid from a food container. Below that, to the left, a laminated prayer card carried by slain American Airlines Flight 77 Capt. Charles F. Burlingame III from his mother’s funeral a year earlier; to the right, a piece of an engine of crashed United Airlines Flight 93.)

It is with Irving Penn’s sensibility that Henry approached the project. Together with his picture editor Todd James he played the role of storyteller—but without the human protagonists. As Henry explains: “When we photograph objects, we are photographing the people. We are just not focused on them.” All that remains is their trace. (Pictured below, the boots of Port Authority Sgt. John McLoughlin, who was buried for 22 hours in the rubble before his rescue.)

“It is,” Henry says, “definitely one of the most humbling portfolios I have ever worked on in my life. Nothing comes close.”

Henry’s collection of these photos, titled “Sacred Dust,” will be exhibited through September 26 at the Foley Gallery in New York; they then will be donated to the 9/11 museum.

If you want to get our Photography newsletter each week, sign up here.

BEING THERE (PART II)

Aftermath: The attack Henry Leutwyler witnessed spurred the longest war in U.S. history. And Kiana Hayeri captured that war in Afghanistan until America’s final days there. Late last year, we assigned Kiana to photograph, in her own words, a “love letter to a troubled Afghanistan” in anticipation of the 20-year 9/11 anniversary. Then, one day in August, after living in Kabul for seven years, Kiana was told she had 15 minutes to pack for a flight out of the imploding nation. Days later, she wrote: “If only I knew this [assignment] was going to be my goodbye letter.”

That “love letter,” she added, turned out to be “about 20 years wiped in 20 days.” (Pictured above, at left, Sumbul Rhea, 17, studied at Afghanistan’s National Institute of Music—and her father was targeted by the Taliban for letting her study music; at right, Taliban recruit Samiullah, 16, in a juvenile rehabilitation center after being accused of planting a bomb attack; below, families grieve at the graves of some of the 90 victims of a May 2020 school bombing in Kabul.)

Some feelings can’t be properly captured by photography, Kiana says—such as the day she rushed out of her longtime home, the same day Kabul fell. “This is the part that I don’t think any camera would have ever been able to capture, even if you had the time and the peace of mind to like stay and shoot, is … it’s the fear. It was the vibe. Everyone was just really scared.”

First-person: An inside look at the fall of Kabul

Related: The end of the Afghanistan I knew

IN A FEW WORDS

Educated girls grow to become educated women, and educated women will not allow their children to become terrorists. The secret to a peaceful and prosperous Afghanistan is no secret at all: It is educated girls.

Shabana Basij-Rasikh, President, School of Leadership Afghanistan

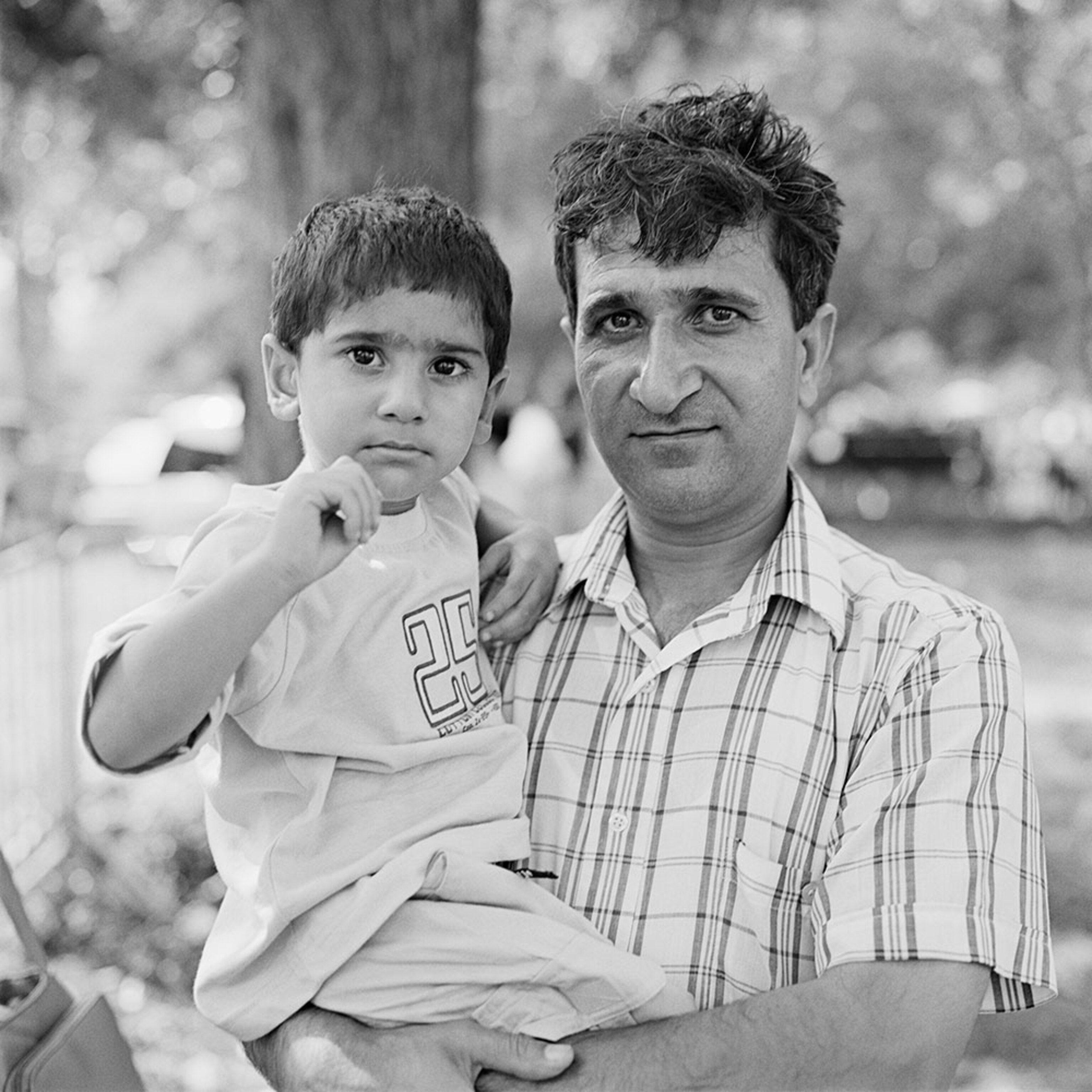

INSTAGRAM OF THE DAY

Two decades: As a 19-year-old in the summer of 2002, photographer Lucas Foglia spent his spare moments wandering New York City with a 1973 Hasselblad, asking people if he could take their picture. He wanted to show a city scarred but healing from 9/11, and more than 1,000 people that summer trusted him to create a portrait. Years later, he got back in touch with some of those people, and their images and stories are among those collected in his just-published book, Summer After. (Pictured above, Abu Huraira, in the arms of his father, Afzal Huraira, in 2002. Abu told Lucas he had no memory of 9/11, but years later, learned that his aunt’s boyfriend had been killed in one of the towers. The two Hurairas have remained extremely patriotic, even with post-9/11 prejudice directed at people of color. “I always felt closer to the victims, yet I was grouped in with the perpetrators,” Abu says.)

This special edition of the Photography newsletter has been curated and edited by David Beard and Monica Williams, and Jen Tse selected the photographs. Amanda Williams-Bryant, Rita Spinks, Alec Egamov, and Jeremy Brandt-Vorel also contributed this week. Have an idea or a link? We’d love to hear from you at david.beard@natgeo.com. Thanks for reading!