So fast, and so few

In this newsletter, how you can help stop the cheetah trade; the worms that thrive in glaciers; discovering a long-extinct baby giant turtle; how animals survive in drought

This article is an adaptation of our weekly Animals newsletter that was originally sent out on August 19, 2021. Want this in your inbox? Sign up here.

By Rachael Bale, ANIMALS Executive Editor

When I went to Somaliland to report a story about cheetah cub trafficking, I had a vague idea I’d focus the piece on a man called Cabdi Xayawaan (AB-dee HI-wahn). He’d been arrested in Somaliland on suspicion of smuggling cheetah cubs, and he potentially faced a major prison sentence.

Everyone I talked to in Somaliland knew of him. At a remote coast guard station, the officers had spray-painted his name on the wall to remind them he was at the top of their unofficial “most wanted” list. The commander of an army garrison that oversees a large part of western Somaliland told me he’s “the worst trader” of cheetahs, responsible for pushing them toward extinction. Even one of Cabdi Xayawaan’s own guys, a cheetah broker who serves as a go-between for Cabdi Xayawaan and people with cubs to sell him, called him “a man who doesn’t have a soft heart.”

I guess he has to be. To be able to buy and sell cheetah cubs, to know they’ve been taken from their mothers, to put them in bags in the back of your car for a long, rough drive, to load them on a boat for journey across the gulf that’ll end in them being sold into captivity for the rest of their lives—either he’s really, really good at compartmentalizing or, as the broker said, he “doesn’t have a drop of mercy” in his body. (Above, five rescued cubs; below, Cabdi Xayawaan in a courtroom cell during his trial for trafficking.)

For two years, I worked with photographer Nichole Sobecki and Nat Geo grantee Timothy Spalla, who leads a team of investigators in Somaliland, to figure out how the trade works, who’s involved, and what’s driving it. You can read about all that—and what happened to Cabdi Xayawaan—in our story, published in the September issue of Nat Geo.

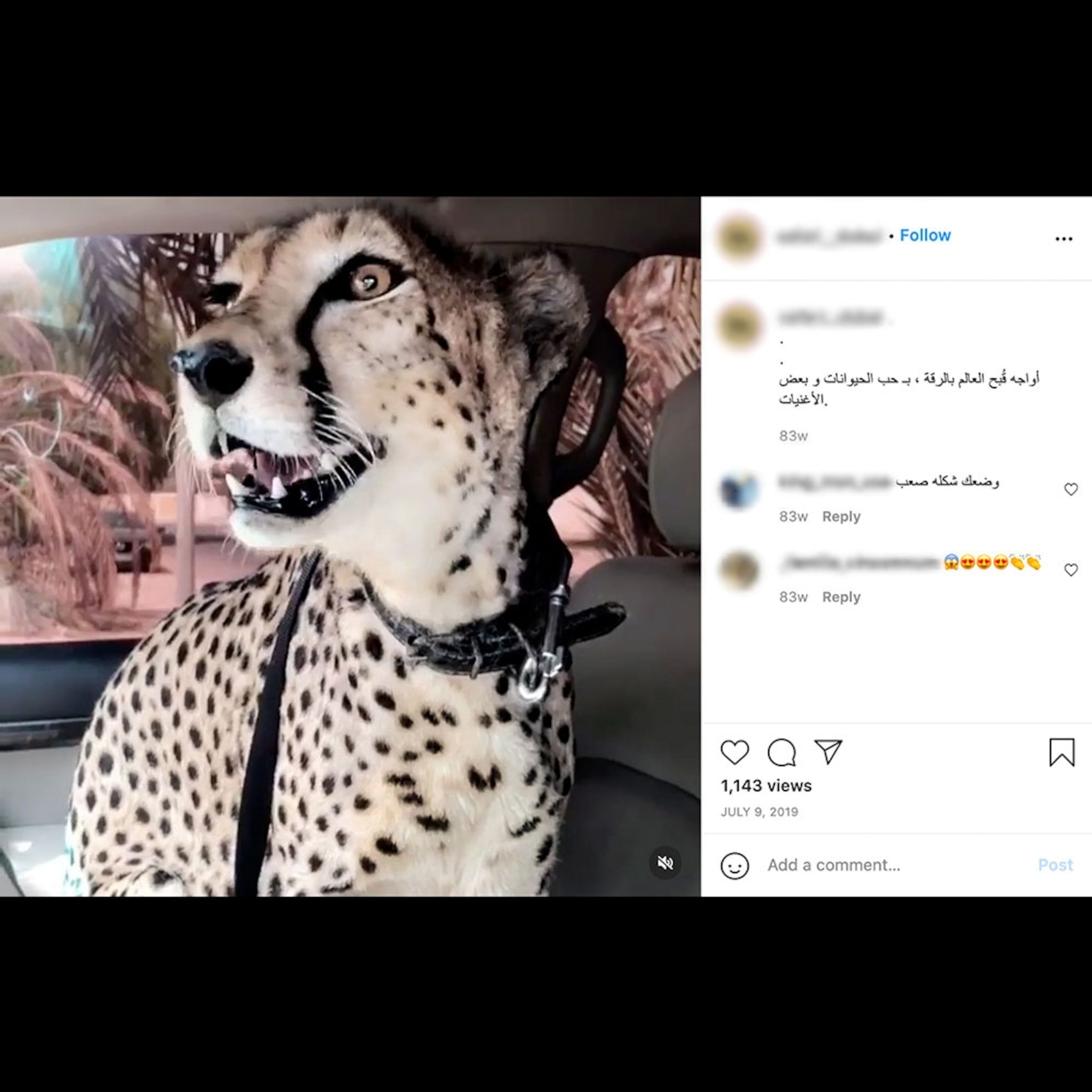

For the moment, I’ll mention one last thing, and that’s the role we play in encouraging the trade. Think about it: When someone on Instagram or TikTok posts a photo or video of their “pet” cheetah, it gets a lot of likes and a lot of comments. (Below, an Instagram post from the Persian Gulf is pictured, showing positive comments and likes, and other details blurred to avoid promoting the account).What people don’t realize is that there’s no commercial cheetah breeding for pets—nearly every one of these animals was taken from the wild illegally. (And even if there were commercial cheetah breeding, they’re still wild animals, not pets!)

Engaging with those kinds of posts amplifies them to a bigger audience, and all that does is increase the demand for cheetahs even more. There are only about 7,000 adult cheetahs left in the wild, and the illegal wildlife trade is only one of a number of threats the species faces. Cheetahs can’t afford to lose new generations of cubs, which is why Nat Geo is asking you to raise awareness by sharing the article and to #ThinkBeforeYouLike a post of someone with a “pet” cheetah.

The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, helped fund this story through Wildlife Watch, an investigative reporting partnership with us.

Hear more about the battle to stop cheetah trafficking in the Horn of Africa on our podcast, Overheard at National Geographic.

INSTAGRAM OF THE DAY

Have a pheasant day: When we think about iconic birds of Japan, it’ s often the red-crowned crane that comes to mind. But the green pheasant, a subspecies of common pheasant found only in Japan, that’s the country’s national bird. Their black feathers can appear green depending on the light. Like other pheasants, the males try to have multiple female mates and will fight each other for them. After the eggs are fertilized, the female will leave the male—and raise the chicks alone.

Basic instincts: How pheasants, peacocks, and swans mate

TODAY IN A MINUTE

The pork industry’s reckoning: In 2018 Californians voted to ban the sale of meat from pigs born to sows born who spent their pregnancy in tiny crates, a move that has ripple effects for pork producers nationwide, Natasha Daly reports. The law is set to go into effect in January, which means the industry—much of which is opposed to it—is running out of time to comply. About 125 million pigs are slaughtered for meat in the U.S. annually. (Pictured above, pigs arrive at a slaughterhouse in Los Angeles in 2019.)

Not just any turtle egg: Tens of millions of years ago, the turtle that laid this egg had a shell that was as long as a person is tall. At first researchers thought the billiard ball-size egg belonged to a dinosaur, but Maya Wei-Haas writes how they discovered, entombed in the egg’s rocky confines, the remains of a long-extinct turtle.

Ew! You don’t see ice worms often. About a half-inch long and thin as dental floss, they live inside glaciers, until they emerge en masse, slithering atop the snow and ice. As glaciers melt, scientists seek to understand how these worms thrive in freezing conditions, Douglas Main writes. See the worms!

Calls for help: With the CDC’s eviction moratorium ending October 3, animal welfare advocates fear that families will be displaced, sending many pets into limbo, too. Animal shelters already are full, the Washington Post reports.

Incredible shrinking animals: Animals across the world are shrinking in size, and research suggests climate change is to blame. These changes might make animals more susceptible to predation, producing fewer offspring, and drying out in droughts, Vox reports. These changes could eventually push some species closer to extinction.

THE BIG TAKEAWAY

Long pregnancy: Consider elephant moms, who for nearly two years go about their daily tasks while pregnant before they deliver their young. On the upside, a baby elephant is born not only able to walk, but to walk long distances. That’s just one of 5,400 mammal species with different pregnancy stories, Lavanya Sunkara writes for Nat Geo. (Pictured above, the foot of an unborn elephant shown in a simulation created for the National Geographic series Growing Up Animal.)

IN A FEW WORDS

For an instant, the divide between us and the cheetah slips away.

Nichole Sobecki, Photographer, Nat Geo Explorer

THE LAST GLIMPSE

Miracles of adaptation: How do animals survive when water is scarce? Prairie rattlesnakes turn their bodies into rain-collecting bowls. Camels have noses designed to reduce the moisture normally lost while breathing. A chimpanzee (illustrated above) can drink from leaves soaked in fresh rainwater, Jason Bittel and Diana Marques report for Nat Geo.

This newsletter was curated and edited by David Beard and Monica Williams, and Jen Tse selected the images. Do you have an idea or a link for the newsletter? Let us know at david.beard@natgeo.com, and happy trails ahead.

PREVIOUSLY ON NAT GEO TODAY...

• A 17,000-year-old woolly mammoth’s tusk tells an extraordinary Ice Age story

• How goats have come to help Kenya’s baby elephants

• In Afghanistan, history came to the Taliban’s aid

• How the declining Colorado River has forced America’s parched West to deal with less water

• When travel transforms into transcendence

• The surprisingly bucolic twists in a walk through San Francisco