Taking the long road back to a stable climate

In today's newsletter, dismantling fences to help wildlife; Canada’s salmon at risk; what you should know about climate change; recycled swimsuits.

This article is an adaptation of our weekly Planet Possible newsletter that was originally sent out on August 24, 2021. Want this in your inbox? Sign up here.

By Robert Kunzig, ENVIRONMENT Executive Editor

The news is relentless sometimes. While we were wondering whether Henri would become the first hurricane in decades to strike New England, flash floods in Tennessee killed at least 21. While American eyes have been focused on fires in the West, more than 15 million acres of forest have already burned this year in Siberia, as Madeleine Stone writes for Nat Geo—an area nearly the size of West Virginia.

Over the next few decades on the climate beat, there will be a lot more seasons like this one. Things are going to get worse before they get better, the recent IPCC report tells us. A UNICEF report released last week found that a billion children worldwide are vulnerable to the effects of climate change. The “picture is almost unimaginably dire,” UNICEF executive director Henriette Fore said. (Above, a family enjoys the beach despite the thick smoke over Yakutsk, in east Siberia.)

History expands the imagination. Picture this planet a century ago: World War I had just killed 20 million people and the influenza pandemic at least 50 million more. The next 25 years would see a global economic depression and World War II, which killed another 60 million. If any period in human history was apocalyptic, it was the first half of the 20th century.

But the second half saw the greatest improvements ever in humanity’s material well-being—especially in child mortality, which plummeted. Globally, it’s about a fifth what it was in the middle of the 20th century.

All that progress was powered by fossil fuels, which means it came at the expense of the global environment—a realization the world is now very belatedly acting on. What form will that action take over the rest of this century? (Below, Elizabeth Yefimova, 18, and Ilya Alekseyev, 20, wear respirators as thick smoke hangs over Yakutsk.)

As Stone explains in another piece for us, the IPCC considered five scenarios. In the first two, global greenhouse gas emissions start declining by 2025, and by the second half of the century we’re drawing massive amounts of carbon back out of the atmosphere. Those scenarios keep global warming below the Paris Agreement target of 2 degrees Celsius. Both are decidedly optimistic—but as climate scientist Zeke Hausfather told Stone, “very much on the table” if major countries meet the net-zero pledges they’ve been making.

The last two of the five IPCC scenarios describe “a dark future…and a strange one,” Stone writes. In the dark future, nationalism replaces global cooperation, population soars to 12 billion, and greenhouse emissions, instead of falling, double by 2100. In the strange future they even triple. The world goes all-in on fossil-fuel-driven growth, burning through more coal than we even know we have. The planet’s temperature rises, in the IPCC’s best estimate, by 4.4°C, or 7.9°F.

Since global coal consumption has actually been declining in the past decade, the IPCC’s most dire future is also its most unlikely. To be sure, it’s not impossible—the Siberian fires, which have released about as much carbon as Germany does in a year, almost 800 million metric tons, are a reminder of the climate feedbacks that could yet haunt our future, even if we’re not so dumb as to quintuple our coal burning. But it’s also not the road we seem to be on.

We seem instead to be traveling the middle of the IPCC’s five roads: the one where the nations of the world muddle along, slowly getting their act together, shifting away from fossil fuels and reducing emissions to near zero by the end of the century. The planet warms, in the IPCC’s best estimate, around 2.7° C, or less than 5°F—which is way too much, but closer to the path we want. (Pictured above, plants climb the red trellises in Singapore's Gardens by the Bay.)

The 21st-century road back to a stable climate will be long, as was the road back from almost unimaginable global destruction in the 20th century. Even on the 2-degree or 1.5-degree routes, there will be many more news seasons like this one. But if we can manage to see them as grievously hard bits of road, rather than harbingers of the apocalypse, we’ll be more likely to get home.

If you want to get this email each week, join us here and invite a friend.

Learn more:

Seven things to know about climate change | Wildfire smoke is transforming clouds, making rainfall less likely | How extreme fire weather can cool the planet

Tips:

Five eco-friendly ways to start the school year

How to keep the planet clean this summer

Earth-friendly shopping

Why tiny forests are popping up in big cities

TAKE FIVE

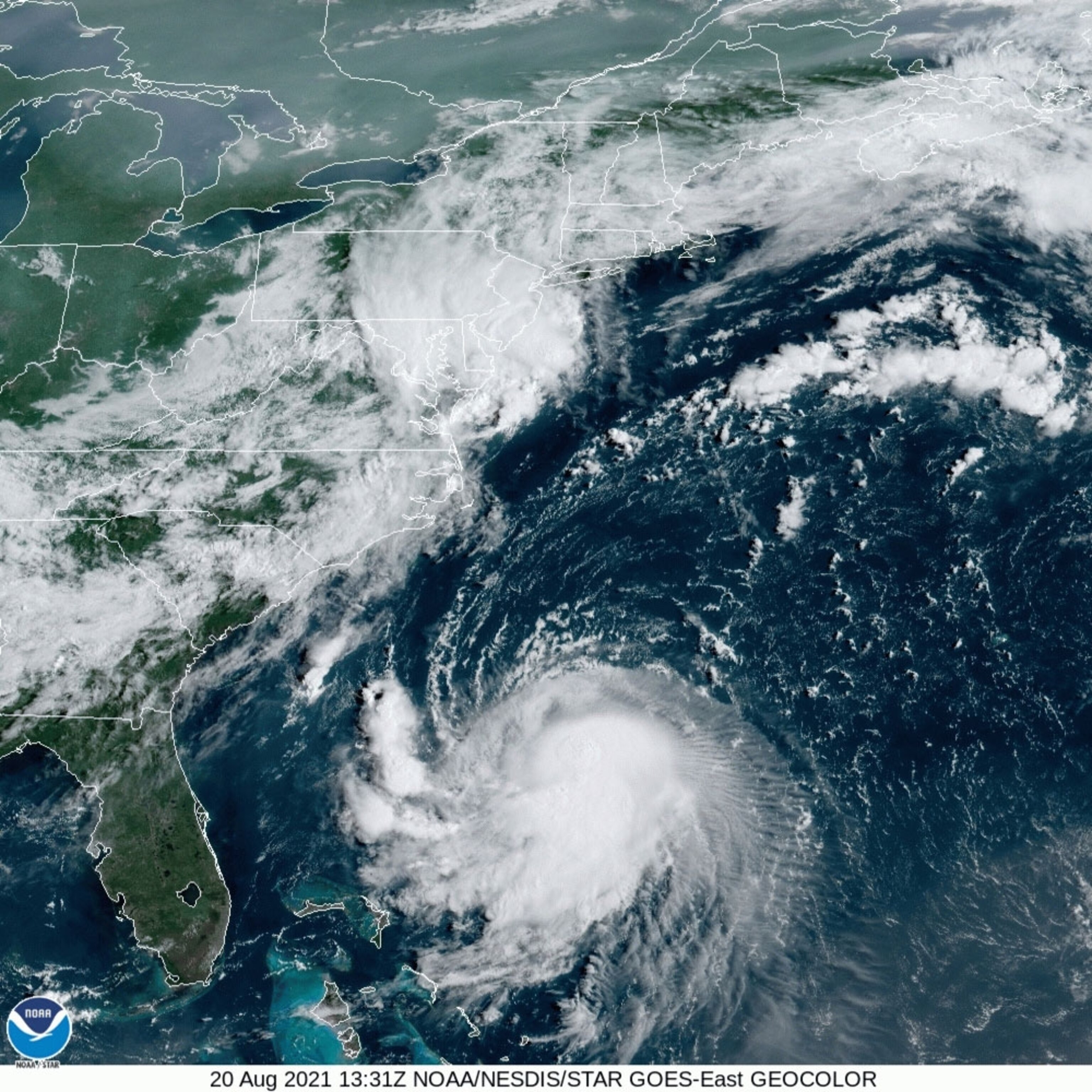

- Why New England rarely sees hurricane threats like Henri (Above, Henri off the coast of Florida on Aug. 20)

- EPA will ban a farming pesticide linked to health problems in children

- If you’re shopping for a new swimsuit, try a recycled one

- The U.S, city that has raised $100m to climate-proof its buildings

- How Indigenous communities are creating energy sovereignty

PLANET SMART

Breaking barriers: Land managers and conservation groups are increasingly aware of how fences can harm wild animals, and they are beginning to push to remove or replace fencing that’s now both useless and an eyesore, Nat Geo reports. Scientists conservatively estimate that more than 600,000 miles of fences crisscross the American West. (Pictured above, barbed wire disappears to the horizon in Wyoming, where a single county has been found to have 4,500 miles of fencing.)

ONE MOMENT

Staying cool: Polar bears spend so much time in the water that they're classified as marine animals. In one case, a mother bear was recorded swimming more than 400 miles in search for food, losing a cub in the process. With ice receding more rapidly in the Arctic, the summer season is elongated, placing higher pressure on the survival of these animals. (Pictured above, a polar bear gracefully swims through crystal-clear water off the coast of southern Greenland).

Subscriber exclusive: See what happens when a polar bear finds a camera

IN A FEW WORDS

I’ve heard the argument that when climate change becomes a real issue, we’ll have the technology to solve it. We’ll grow plants in space. We’ll terraform Mars. But climate change is here. And I wonder if we’re ready."

Lillygol Sedaghat, Geographer, Nat Geo Explorer

FAST FORWARD

At risk: Pacific salmon are in a state of decline. The threats against them and their habitats are myriad—climate change, pollution, pathogens from open-net fish farms, overfishing, plus human infrastructure. Chefs and conservationists in British Columbia are saying that to save the region’s endangered signature fish, people need to halt their salmon consumption. (Pictured above, Canada pink salmon, one of five species of salmon, in British Columbia).

How you can help save salmon

1. Patronize restaurants that make sustainable seafood a priority

2. Avoid eating Pacific wild or farmed salmon

3. Fishing in Canada or the Pacific Northwest? Hire a licensed local guide

Go deeper: How to feed the world without destroying the planet

We hope you liked today’s Planet Possible newsletter. This was edited and curated by Monica Williams and David Beard, and photographs were selected by Heather Kim. Have any suggestions for helping the planet or links to such stories? Let us know. Thanks for stopping by!