These tiny creatures are marvelous

In today’s newsletter, we discover the miraculous, miniature life forms that make a forest grow, examine when face masks were scandalous, learn why inspiration often strikes in the shower … and witness the evacuation of a 500-year-old mummy. Plus, Leonardo da Vinci’s secret.

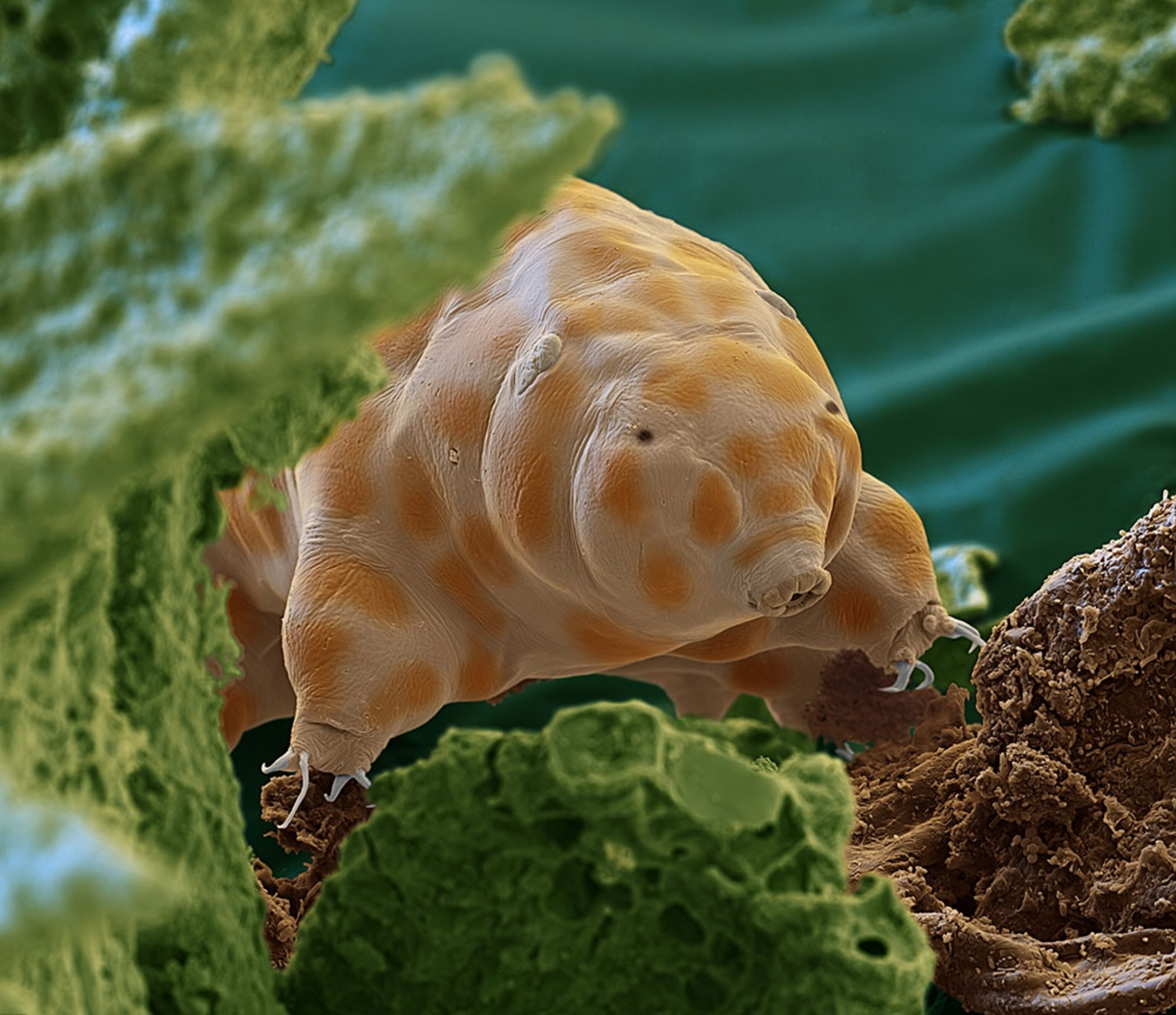

What makes a forest grow? A photographer and biologist put microscopic fungi, roots, and slime molds from Germany’s Black Forest under a scanning electron microscope—and found creatures like this astounding tardigrade (above) among the forest’s essential, and often overlooked, life forms.

This discovery in the moss on a tree trunk, magnified 2,400 times, marked a newfound species among the 1,300 known types of tardigrades, says photographer Oliver Meckes. “We always thought we knew a lot about the cycles of life and what happens to a tree when it falls and decays,” Meckes tells our French edition colleague Marie-Amélie Carpio. “But what we learned with this assignment was how complex these processes are, and the myriad creatures involved!”

See the full story here—and other small-scale discoveries below.

Please, consider getting our full digital report and magazine by subscribing here.

What are these egglike spheres? Fungi like this Resinicium bicolor—shown magnified 7,000 times—start breaking down dead trees by digesting lignin, the complex compound that helps form woody cell walls in plants. There would be no soil without microscopic life, including fungi, mites, and worms.

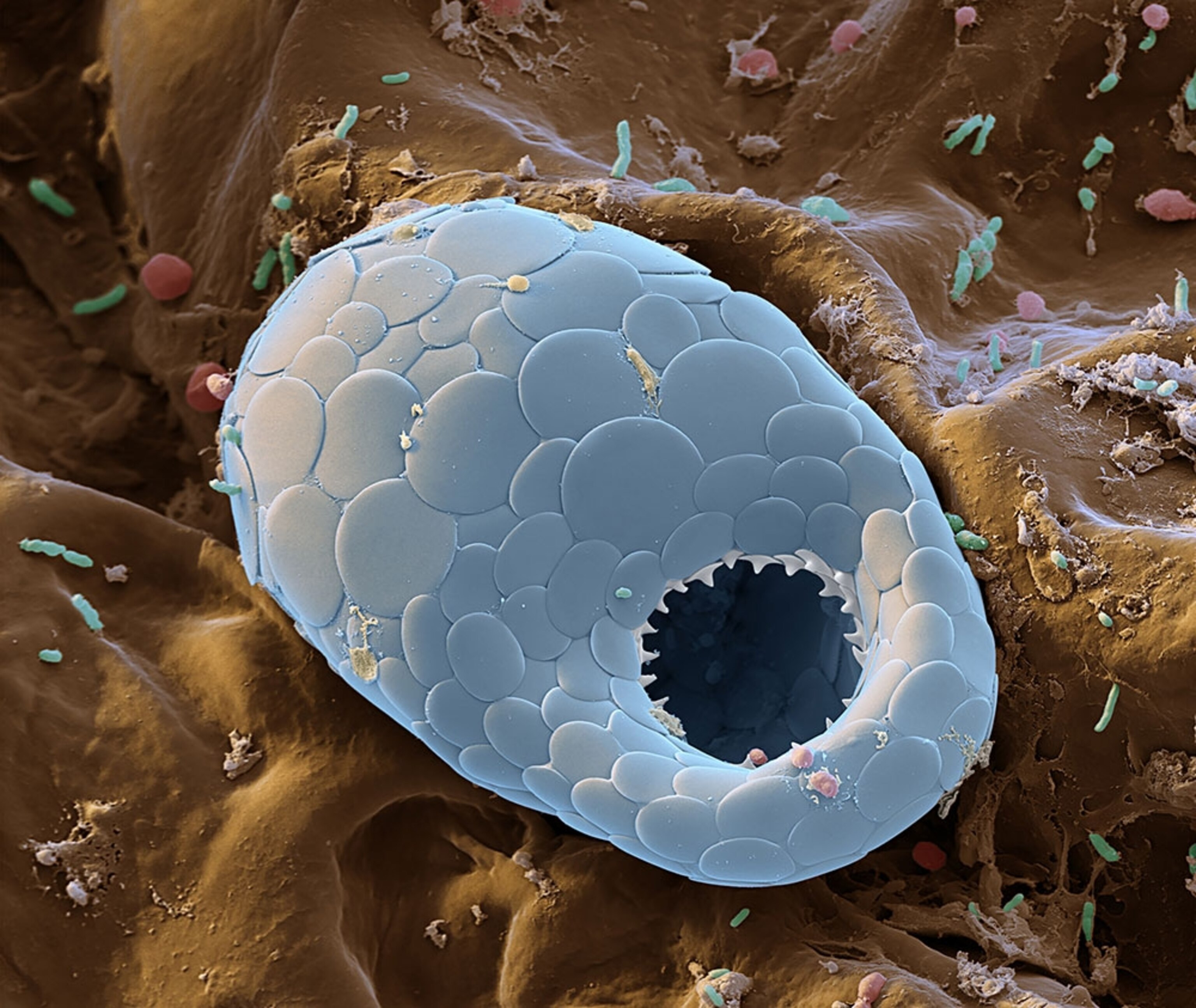

Magnified 14,000 times: Scales of silica cover the single-celled body of a testate amoeba. These types of amoebas are named for the hard shells they create, possibly for protection against environmental changes within the forest litter.

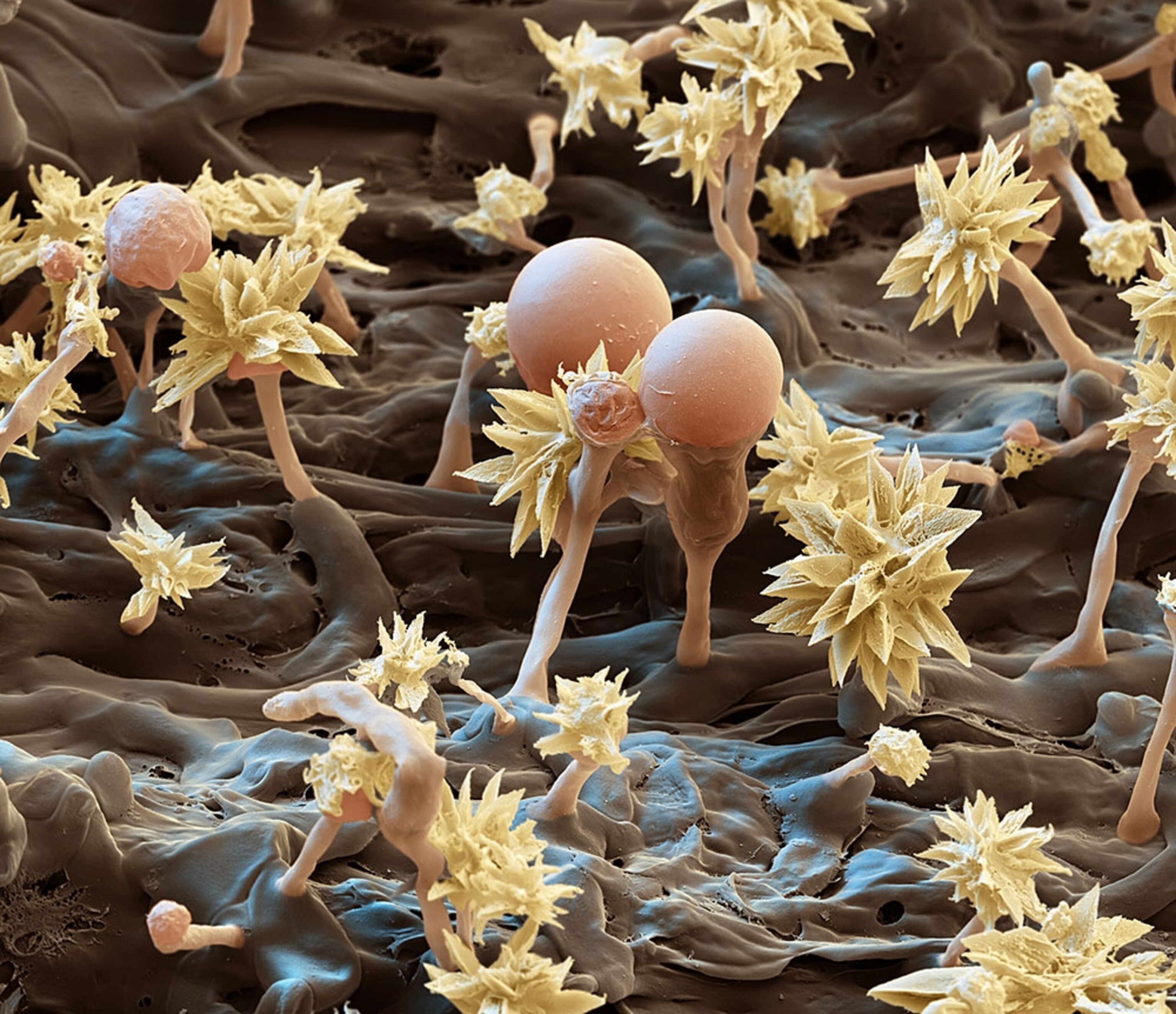

‘Good’ slime: Resembling a fairy’s gift basket, the fruiting body of a slime mold, magnified 400 times, releases spores from its perch on woody debris draped in fungal filaments. Slime molds feast on other microbes found in decaying plant matter.

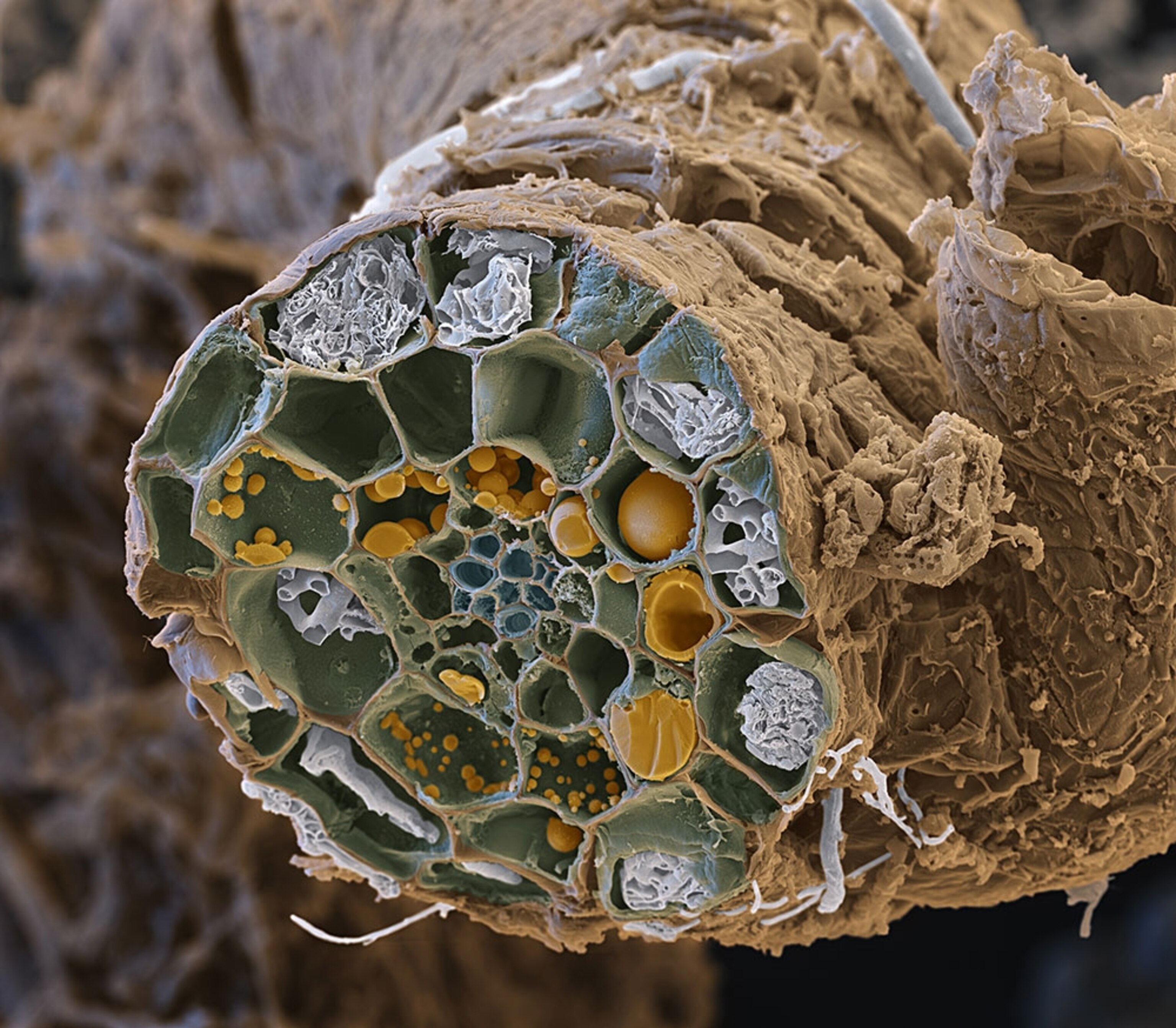

A kind of honeycomb? Some mycorrhizal fungi make their homes inside plant cells, as seen in this cross section of a European blueberry root. This allows soil residents of very different sizes to exchange nutrients—helping the forest. This image is magnified 2,200 times. See more here.

STORIES WE’RE FOLLOWING

• See: How life for one family in Afghanistan has changed in the year since the U.S. pulled out

• Staid? Try scandalous! That was the view of these early, fashionable face masks

• From vision to intention: How the ‘Mona Lisa’ painter outlined his world-changing inventions

• Why do great ideas flow in the shower? Science has an answer

• Map: 75 years ago, here’s the traumatic way that India was split

PHOTO OF THE DAY

Evacuated: This 500-year-old mummified chamois, an Alpine goat-antelope mix, lies exposed on an Austrian glacier near the Italian border. The remains of a young female were taken from the rapidly melting glacier to preserve them, Nat Geo reports.

IN THE SPOTLIGHT

Who helps America? At a time when the U.S. seems to be getting torn apart, photographer and Nat Geo Explorer Andrea Bruce has focused on people building community in the 246-year-old democracy. A new Nat Geo story spotlights people helping others, driven by a deep need that unites people. Members of the Blackfeet Nation’s Tatsey family (pictured above) help connect tribal children with their ancestry.

IN A FEW WORDS

When people get shot, journalists cover it in a way that’s ‘this has got to stop’ but there is no critique of the system that puts people in a terrible situation consistently. Why are we there besides taking photos and film?Carlos Javier Ortiz, Cinematographer, documentary photographer, and Nat Geo Explorer who focuses on urban life, gun violence, and racism in marginalized communities

LAST GLIMPSE

Sleepy time: Even as a drone hovered above to get this image, a large male polar bear that photographer Martin Gregus, Jr. calls Scar never stirred in this bed of fireweed. Gregus says he named many of the bears in hopes it would help people relate to them as individuals needing protection. He spent two months in the Canadian Arctic and his photos reveal a softer side of the world’s largest terrestrial predator. “You always see polar bears on ice and snow,” he says. “But it’s not like they stop living in the summertime.”