WHY HUMANS TURN TO RITUALS IN TOUGH TIMES

This article is an adaptation of our weekly Science newsletter that was originally sent out on January 13, 2021. Want this in your inbox? Subscribe here.

By Victoria Jaggard, SCIENCE executive editor

As a proud science geek, I’ve never been particularly superstitious. I spill salt with abandon; I married a man born on the 13th of a month; I let a black cat cross my path for almost 17 years. And yet, I instinctively say “bless you” when someone sneezes. That’s not being superstitious—I certainly don’t think I’m preventing someone’s soul from escaping their body. It’s just polite.

As it turns out, a lot of the social norms we practice today may have had their roots in various attempts to ward of disease and disasters. As Tim Vernimmen reports for Nat Geo, for a long time, the shrouded origin of a ritual was one of its defining characteristics. “Rituals can reinforce a sense of community and common beliefs,” he writes. However, the diversity of these kinds of cultural practices “can also alienate and separate people, particularly when the valued rituals of one culture strike another as bizarre.” It’s tough to defend a treasured practice when you can’t rationally explain why you’re doing it.

For many rituals, this enigmatic nature will endure. But sweeping research from a number of disciplines now shows that various human cultures today practice certain behaviors because people once thought it would keep them safe, even if the initial reason for the behavior has long been forgotten. For instance, cognitive scientist Cristine Legare of the University of Texas at Austin documented 269 rituals associated with pregnancy and birth that are still practiced in the Indian state of Bihar, where maternal and infant mortality is high. Crucially, a significant proportion of these rituals are perfectly consistent with modern medical advice, Legare says.

Today, the COVID-19 pandemic has us adopting behaviors that, for all we know, could be mysterious but omnipresent rituals in a few hundred years. People of the future may be singing a 20-second handwashing song or giving each other elbow bumps long after COVID-19 has been conquered. And while I certainly hope they won’t be the only potential legacies of this pandemic, the ‘90s girl in me loves the prospect of my far-flung descendants lightly humming the chorus to Alanis Morissette’s “Ironic” without any real idea why. (Pictured at top, celebrants of the Hindu Vedic festival of Chhath Puja often bathe in holy water, abstain from food and drink, and stand in the water for at least one hour to seek protection for their families.)

Do you get this newsletter daily? If not, sign up here or forward to a friend.

TODAY IN A MINUTE

The polar vortex: It’s back—and apparently split in two. The phenomenon known as the polar vortex is likely to bring super-frigid weather to America’s Midwest and Northeast, as well as the mid-latitude regions of Europe, in the next week or two, scientists say. The Big Chill could last in fits and starts through February, writes Nat Geo’s Sarah Gibbens.

Secret signs: From Viking hammers to flags of fictional countries, many of the Capitol rioters shared an inside visual handshake to acknowledge their white nationalist identity. Nat Geo’s Kristin Romey decodes the meaning of the obscure hate symbols, paraded on flagpoles or tattooed on the skin of seditionists, that often harken back to an idealized history with white Christian men placed front and center.

Opening up vaccinations: The slow—and fitful—U.S. efforts to vaccinate Americans against COVID-19 will be broadening under federal proposals. Both the outgoing Trump and incoming Biden administrations aim to release all available vaccine doses to speed inoculations, Jillian Kramer reports. The Trump plan urges states to open access to anyone 65 and older, the Washington Post says. U.S. health officials report more than 22.8 million cases and 381,000 deaths in America from the virus. A record-high 4,406 COVID-19 deaths were reported Tuesday.

A lesson in conservation: What can a community do to help Earth? A Thai village beset by declining fish counts set aside a stretch of its river as a no-fish reserve—and a quarter century later it is reaping the benefits. The protected section of the river in northwest Thailand brims with large barb and mahseer (a kind of carp). Catches outside of the reserve, where the villagers fish, have significantly increased, Rachel Nuwer reports.

INSTAGRAM PHOTO OF THE DAY

After sunset: Photographer Babak Tafreshi caught an impressive display of lenticular clouds right after sunset in Iceland. These clouds form when strong, moist winds blow over rough terrain, such as mountains or valleys. Some lenticulars are reported as UFOs due to their flying saucer shapes and the bright reflection of the setting sun, moonlight, or city lights. Pilots try not to fly near these dense clouds to avoid turbulence due to a sudden change of air pressure. This fascinating image has attracted more than 600,000 likes and comments since it was posted on our main Instagram page five days ago.

Learn more: ‘UFO Clouds’ are real. Here’s how they happen.

THE NIGHT SKIES

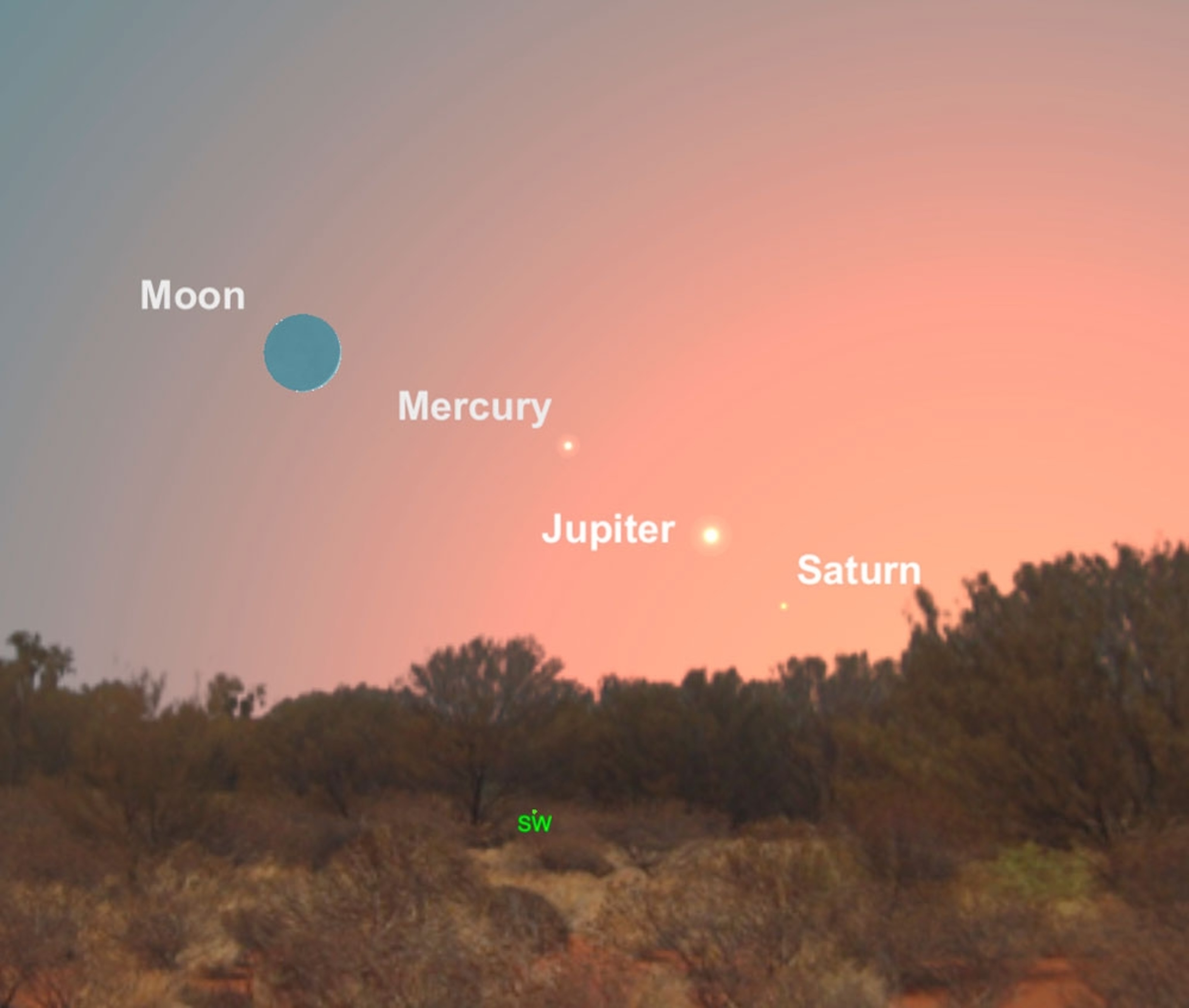

Also after sunset: Sky-watchers may get an eye-catching show just after the sun goes down on Thursday. Saturn, Jupiter, and Mercury will appear in the low southwest sky as bright stars that are in near perfect alignment. What will make this sky event easier to spot—and even more picturesque—is the razor-thin crescent moon that will be next to Mercury. Look closely and observe the moon’s unlit portion, which will be subtly illuminated by a phenomenon known as earthshine. That’s when sunlight bounces off Earth’s reflective clouds and oceans, is cast onto the moon’s surface, and then gets sent on to our eyes. Earthshine is visible for only a few days before or after a new moon. — Andrew Fazekas

See: 10 top stargazing opportunities of 2021

THE BIG TAKEAWAY

Too good to be true: Why do so many people believe and embrace conspiracy theories? Scientists help explain how people latch on to false ideas and misinformation—and how those beliefs can create disastrous effects, such as the storming of the Capitol last week, or a shooting in a Washington, D.C., pizzeria years earlier. Not only is it easier to reach people with misinformation now, the simple explanations provided by conspiracy theories and other falsehoods can be even more appealing during times of turmoil, experts tell us. “It helps restore a sense of agency and control for many people,” says social psychologist Sander van der Linden. (Pictured above, pro-Trump supporters gathering in Washington, D.C., last Wednesday.)

IN A FEW WORDS

For some people, conspiracy beliefs are the best way to deal with the psychological threat posed by their failure.

Marta Marchlewska, Social and political psychologist, the Polish Academy of Sciences, From: How people get hooked on irrational conspiracy theories

DID A FRIEND FORWARD THIS NEWSLETTER?

On Thursday, Rachael Bale covers the latest in animal news. If you’re not a subscriber, sign up here to also get Whitney Johnson on photography, Debra Adams Simmons on history, and George Stone on travel.

THE LAST GLIMPSE

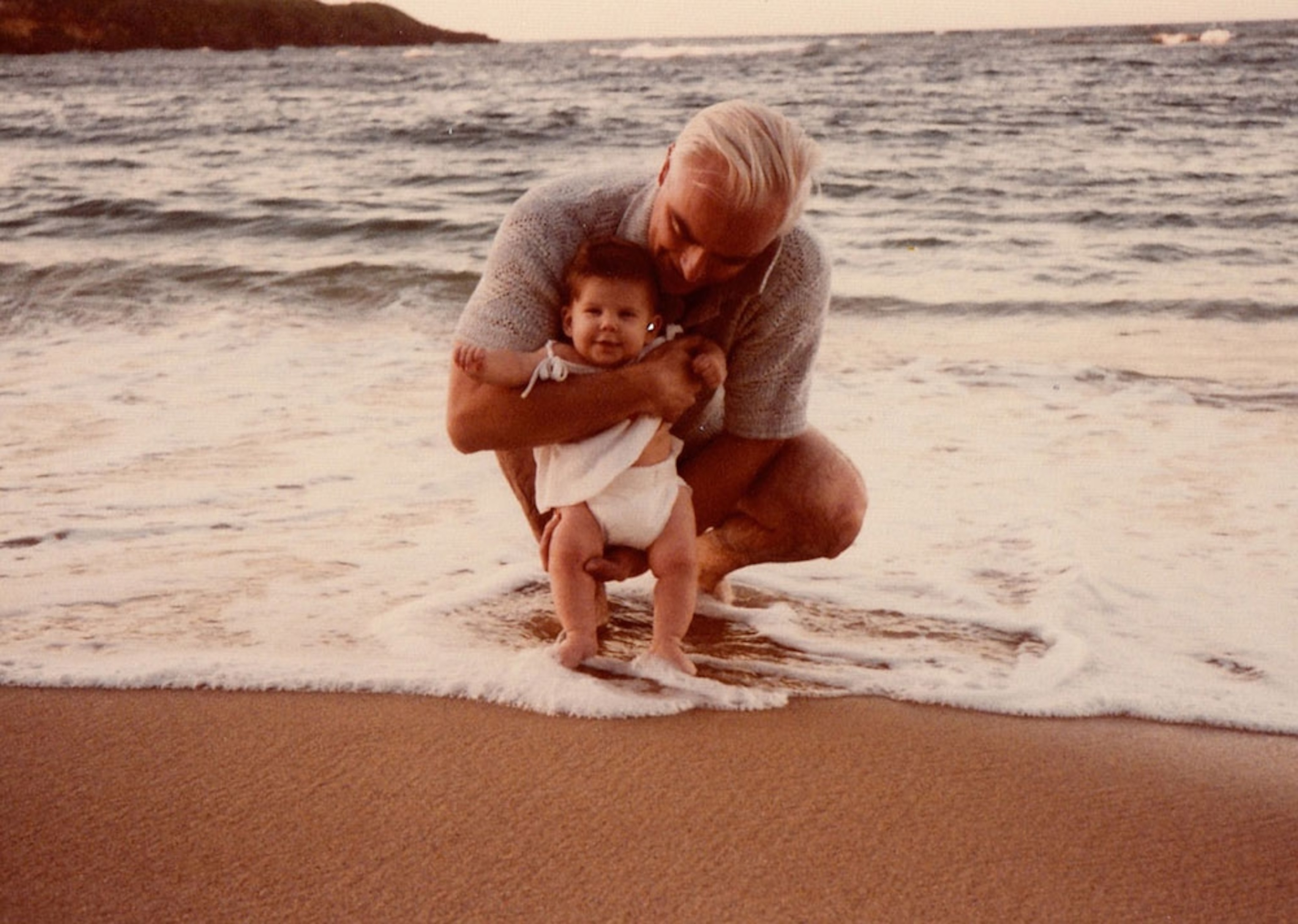

A global (and personal) loss: When the legendary Arecibo Observatory collapsed, science writer Nadia Drake felt the loss to her core. As a little girl, Nadia was able to repeatedly visit the giant, pathbreaking radio telescope in Puerto Rico—because her dad, astronomer Frank Drake, ran the place. She had often seen the same kind of golden light that bathed the observatory the December morning it collapsed. “I’ve watched as dusk washed over the Puerto Rican mountains, summoning the coquí tree frogs to sing their nightly chorus. Each time I said goodbye to the telescope, I thought it would be waiting when I returned.” (Pictured, Nadia as a toddler with her dad on a beach in Puerto Rico in 1980.)

This newsletter has been curated and edited by David Beard, with photo selections by Jen Tse. Kimberly Pecoraro and Gretchen Ortega helped produce this. Have an idea or a link? We’d love to hear from you at david.beard@natgeo.com. Thanks for reading, and have a good week ahead.