Can we make up for lost time?

By Robert Kunzig, ENVIRONMENT executive editor

New Year’s Eve is supposed to be a happy occasion, but saying goodbye to yet another year can also feel a little wistful. Not this time, I reckon. Can you remember a year you were happier to see the back of? 2020 began in the U.S. with the promise of a nasty election campaign and news of a novel virus spreading rapidly in China. It will end with our democracy deeply shaken, more than 300,000 dead, and many more to come before the new vaccines kick in.

But sometime in 2021, we can hope to emerge from this nightmare and turn our minds back to other business.

There’s a lot of environmental business to tend to—and reasons to be hopeful about it, as my colleague Sarah Gibbens reminded us recently. It was a bad year for coal and oil worldwide, but boom times for renewables, which are cheaper than ever. The electric vehicle market is surging, encouraged by governments around the world. A heartening new agreement to protect coastal waters was announced this month by 14 countries, and a few weeks before that, the Atlantic’s largest marine protected area was created. (Pictured above, dusk falls over Yosemite Valley’s attractions, including Half Dome, center left; below, coral spawns on the Great Barrier Reef, left; a view from above of the Great Barrier Reef, right.)

Meanwhile, one of the few things Congress and the Trump administration were able to agree on this year was the Great American Outdoors Act, which will pump nearly $10 billion into long-deferred maintenance for national parks and public lands—more money than the parks have seen in half a century. “It’s incredible to think about how much good this will do,” one activist told Craig Welch.

However, policy measures adopted by the outgoing administration would add around 1.8 billion gigatons of carbon to the atmosphere between now and 2035, Alejandra Borunda reports.

The good news is, that’s only 30 percent of a single year’s emissions. The better news is, those policies are reversible. The real problem is the four years of lost time. It will cost us. But climate change is a problem we’ll be dealing with for decades. And making up for lost time is what new years are for.

Move, downtown Los Angeles in early April. Stay-at-home measures to fight #COVID in Los Angeles left its notoriously gridlocked highways relatively clear. Activity around the world was so low in the spring of 2020, scientists measured less seismic activity.

Do you get this newsletter daily? If not, sign up here or forward to a friend.

Today in a minute

What can one bill do? Tomorrow, the Clean Air Act turns 50. The bill has saved millions of lives and trillions of dollars. “The Clean Air Act remains the most powerful public health law enacted in the twentieth century in the United States,” Paul Billings, a senior vice president at the American Lung Association, tells us. It has has since reduced air pollution in the United States by 70 percent—even as the population, the economy, and the number of cars on roads have grown. More than 60,000 Americans still die prematurely from the effects of air pollution every year, and they are disproportionately poor, Black, and Latino. Read on.

Instagram photo of the day

The sounds of melting ice: “I love describing the auditory notes behind the pixels I’ve chased for years,” says photographer Pete McBride, “those subtle sounds like the ‘applause of rain on rock,’ or the orchestra of dripping, created by melting ice in the Antarctic Peninsula.” The peninsula faces some of the highest temperature increases on the planet and has lost an average of 163 billion tons of ice each year since 2002.

Related: East Antarctic ice sheet is more vulnerable to melting than thought

The night skies

New Year’s fireworks: As darkness falls today, watch for the silvery orb of the last full moon of 2020 to rise in the east as the sun sets in the west. It is also the first full moon of the new season, a week after the solstice, and is known for obvious reasons as the Cold Moon Or Long Night’s Moon. Then late Saturday into early Sunday morning enjoy the first meteor shower of the year, the Quadrantids. For this shower, peak rates usually hover above 60 shooting stars an hour seen from dark locations. But with the waning gibbous moon with its blinding glare dominating the predawn hours of Sunday, the best time to see most meteors will be Saturday night. The meteors will appear to radiate from the northern part of the constellation Boötes, the herdsman, in the northeast sky just off the Big Dipper’s handle.— Andrew Fazekas

Overheard at Nat Geo

How will we feed a growing world? The world is warming. Fires and extreme weather seem to hit farmlands with greater frequency. But there’s a ray of hope. And it starts with microbes. That’s what microbiologist Rusty Rodriguez tells our podcast, Overheard. Since the 1990s, he has examined soil in some of the world’s hottest places and searched for what keeps plants growing. “All of the plants in these hottest zones,” he says, “all had one dominant fungus that we could isolate from them.” (Pictured above, an image of a coastal plant that was sterilized, cut up into pieces, and placed on a petri plate, allowing fungi to grow.)

The big takeaway

Destroyed in minutes: The devastating summer windstorm in Iowa claimed 80,000 trees in Cedar Rapids, two thirds of the city’s canopy. In some areas of the city, the lack of shade will boost temperatures an estimated two to four degrees. It’s going to take a decade to replace the walnuts and sycamores, lindens and honey locusts, but residents vow to do it. “You’re planting for the future,” homeowner Russell Snow tells Nat Geo. “We’re planting for our kids and our kids’ kids. I’ll never see the benefit of a 150-year-old oak tree. But somebody else will.” (Pictured above, Laurie Berdahl stands in her front yard, after the devastating windstorm, called a derecho, on August 10.)

Even strong trees get sick a lot over the course of their lives. When this happens, they depend on their weaker neighbors for support. If they are no longer there, then all it takes is what would once have been a harmless insect attack to seal the fate even of giants.Peter Wohlleben, Author; The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate

Did a friend forward this to you?

On Thursday, Rachael Bale covers the latest in animal news. If you’re not a subscriber, sign up here to also get Whitney Johnson on photography, Debra Adams Simmons on history, and George Stone on travel.

The last glimpse

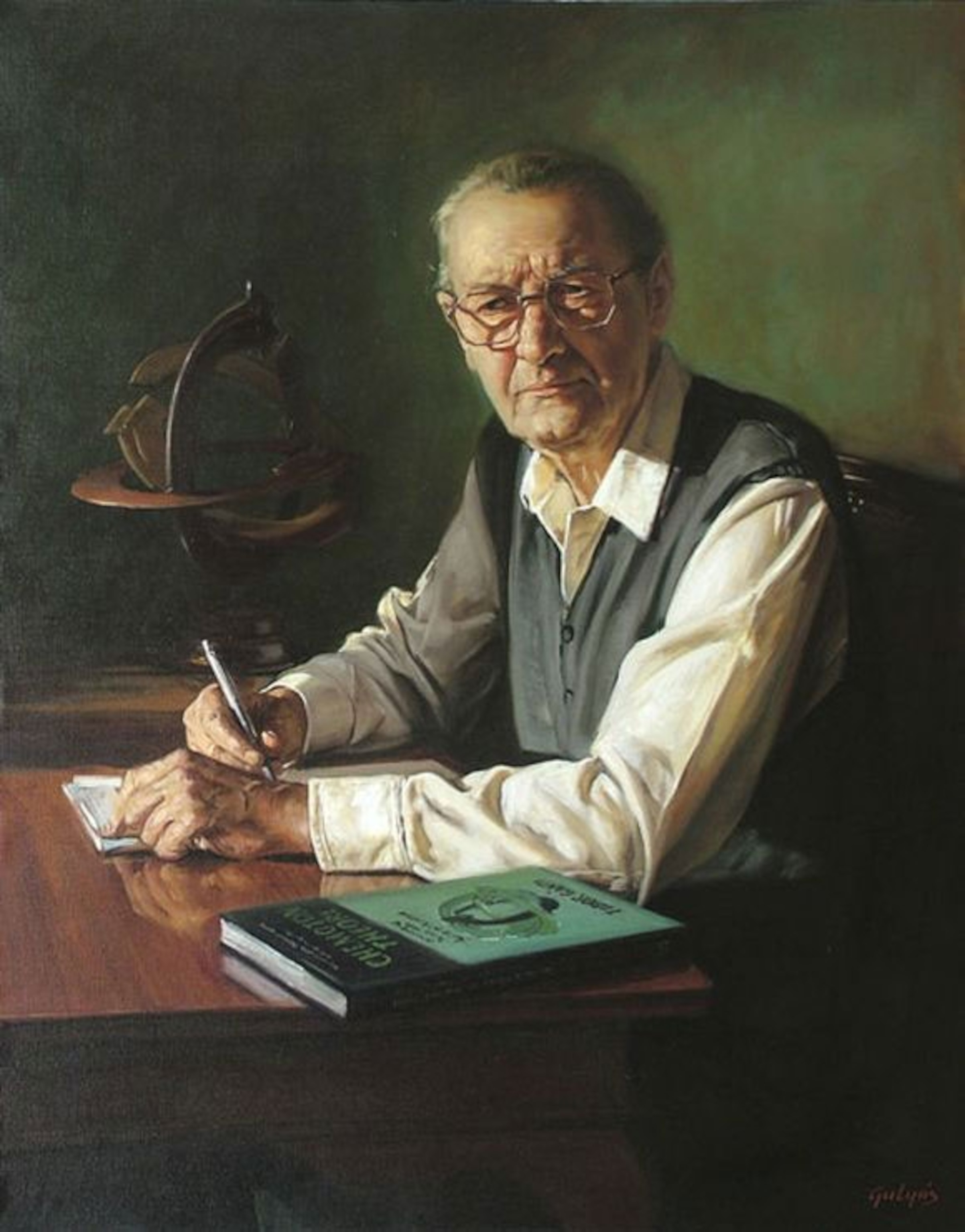

How life begins: More than a decade after his death, Hungarian biologist Tibor Gánti is belatedly being recognized as one of the most innovative biologists of the 20th century. Why? Gánti devised a model of the simplest possible living organism, which he called the chemoton, that points to an exciting explanation for how life on Earth began. Tibor. “I think Gánti has thought deeper about the fundamentals of life than anybody else I know,” says biologist Eörs Szathmáry of the Centre for Ecological Research in Tihany, Hungary. The chemoton is attractive for experiments by chemists and astrobiologists, Michael Marshall writes. (Pictured above, an oil painting of Gánti.)