How do we come to grips with 200,000 dead?

By Victoria Jaggard, SCIENCE executive editor

I know you don’t want to think about this, but please, hear me out. My grandmother died earlier this year, and I flew to Texas just a few days shy of the spring equinox for her memorial service. I knew enough then about the coronavirus to be nervous about traveling, and I endured mocking from relatives for refusing hugs or handshakes, and for using copious amounts of hand sanitizer. By the time I returned to D.C., my office had shuttered, and we were on lockdown in our homes.

It’s now the fall equinox, and the virus has officially claimed 200,000 American lives. That’s a death every 1.5 minutes, on average. Put another way, it’s eight 737s crashing every day since February. Globally, we are nearing a million dead. (Above, a photograph of COVID-19 victim Constance Duncan, 75, placed by her son, Chris, amid 20,000 flags honoring the dead at the National Mall on Tuesday.)

These are grim milestones, and at this stage of the pandemic, people are almost certainly having trouble wrapping their minds around the sheer magnitude of the loss. As Sarah Richards reports for Nat Geo, our biology is working against us. Humans evolved to be altruistic, but there are limits to how much of ourselves we can give. Like someone becoming “nose blind” when they are surrounded by strong odors, people experience “psychic numbing” when exposed to too much suffering.

You don’t need to personally know someone who died to avoid this compassion fatigue. Just hearing or reading about individuals with faces, names, and families can evoke a more powerful emotional response than mere statistics, in the same way that the diary of Anne Frank became a touchstone for understanding the horrors of the Holocaust.

Obviously, self-care is incredibly important right now, and people need to protect themselves mentally as well as physically. But there are healthy ways to process the death toll, even in the midst of so much turmoil. Grief specialist David Kessler recommends using personal connections to motivate positive change, like talking about mutual acquaintances who got sick or who died to encourage friends and family to wear masks. Also remember to keep your “present bias” in check—2020 is not actually the worst year ever, even if it feels that way.

The most important thing any of us can do now is keep fighting to improve our shared situation. There is a path out of this public health crisis, if we stay focused and motivated and make better collective decisions. Then, we can all look forward to whatever 2021 has in store.

Do you get this daily? If not, sign up here or forward to a friend.

(Above, funeral director Omar Rodriguez inventoried bodies, all coronavirus disease victims bound for cremation, in the Gerard J. Neufeld Funeral Home in Queens in April.)

Today in a minute

Too many hurricanes: I get it, there were so many hurricanes this year they ran out of names pegged to letters in the English alphabet. But what’s with this Alpha and Beta stuff? The National Hurricane Center uses the Greek alphabet as a backup, but has only had to use those names twice, Nat Geo’s Oliver Whang reports. Assigning names makes an approaching storm feel all the more immediate, which could make a difference in the way people prepare. “In general, humans care about other humans, so when we humanize something inanimate, it makes us care about the thing more,” says Adam Waytz, a professor at Northwestern University and author of the book The Power of Human. (Above, Hurricane Florence as it churned across the Atlantic in 2018.)

Dino teeth: Five months ago, paleontologists and researchers determined that the Spinosaurus, the giant predator of Jurassic Park fame, was a swimmer. In addition to the findings of its powerful tail, the just-announced discovery of more than 1,000 teeth from the dino reinforced its characterization as an enormous river monster. Nat Geo’s Michael Greshko, who went to North Africa on the successful Spinosaurus dig, tells me the latest discovery is a valuable addition to the insights gleaned from past studies of Spinosaurus’s anatomy, including its unusual, paddle-shaped tail. Greshko will be writing more about the discovery here.

Before Cape Canaveral: The beginnings of the U.S. space program took place far from Florida’s sands. Humans were launched into the stratosphere for two years in the 1930s from the Black Hills of South Dakota, more precisely a 450-foot natural bowl at about 4,000 feet of elevation. Teams strapped themselves to insanely huge balloons, lifting off from the “Stratobowl” and landing hundreds of miles away, Bill Newcott writes. The studies paved the way for more formal space exploration decades later.

Da Da Da: In one of the emptiest of power-grabbing gestures, Russia has claimed that Venus is a Russian planet. The pronouncement was made by the nation’s head of its space agency, who said he wants to send a Russian mission to the inhospitable second planet from the sun, CBS News reports. The claim followed reports this month of possible signs of life on the planet.

What exactly is the equinox (or better yet, when)? So, yesterday the sun passed directly over the Equator, signaling the start of autumn and the coming winter in the Northern Hemisphere (and the start of spring and promise of summertime in the south). Equinox means “equal night” in Latin—the time when daylight and nighttime are (roughly) equally divided. You’ll have to click here to find out why winter is coming for northerners if the sun is actually closest to Earth in December. (Or just keep reading and I’ll tell you at the bottom of this newsletter).

Instagram photo of the day

The birthplace of speleology: Speleology is a fancy word for the study of caves. And Slovenia, which photographer Robbie Shone calls the birthplace of speleology, is famous for its river caves. This cave, Križna jama, features a chain of underground lakes with emerald green water. It’s one of the few touristed caves in Slovenia that doesn’t contain concrete pathways or harsh lighting. Trust me, Robbie knows caves; he wrote for our magazine in August about climbing for his life out of the world’s deepest known cave (below), which was flooding.

Subscriber exclusive: The flood pulse was coming. We had 30 minutes

The night skies

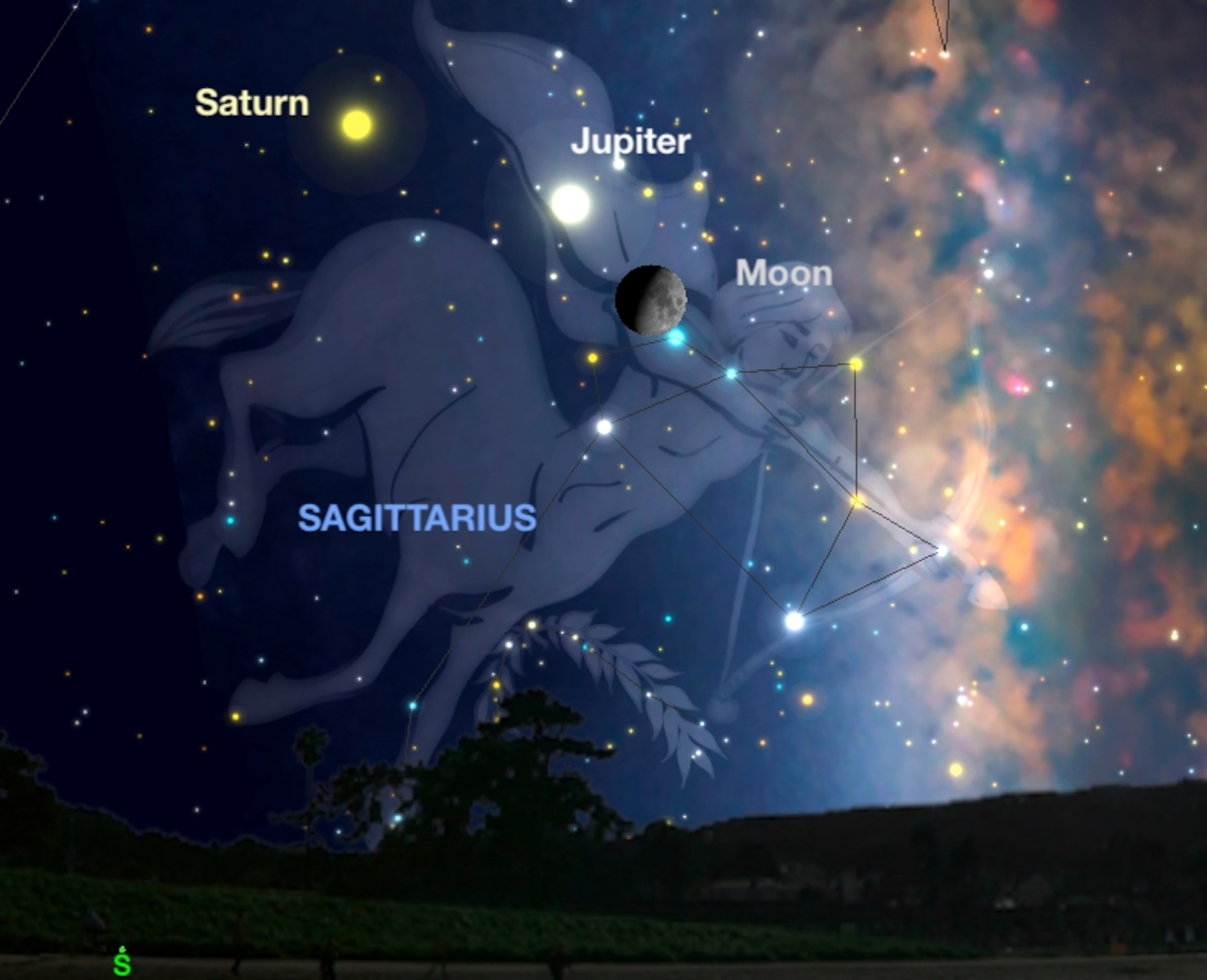

Hello Jupiter: Tomorrow and Friday evening, the waxing gibbous moon makes an impressive close approach with Jupiter and Saturn, which will be appearing in the constellation Sagittarius. Thursday night, the moon will be just off to Jupiter’s right, forming an eye-catching lineup, but by Friday night the moon will have a very close encounter with Saturn. Binoculars will show off Jupiter’s dark brown cloud belts and four main moons, while a small telescope pointed at Saturn will easily reveal its famous rings. (Note: In last week’s column about the Zodiacal Lights, they can be seen about an hour before the sun rises above the eastern horizon, not west.) —Andrew Fazekas

The big takeaway

If time is money ... can money give you time? That’s what researchers are studying while looking at the concept of “subjective time”—how people measure their life on Earth. Granted, wealthier people do live longer. They also often have less dependence on a strict routine, and can pay for novel experiences that will make them think they’ve had a longer time on Earth. However, an inexpensive hike could be more memory filled than an expensive watch, Doug Johnson writes, and biologically, you may be able to stack more experiences in your memory when you are young.

In a few words

Humility before nature and each other is the key. It's our arrogance that has gotten us into so much trouble with nature and has created such anger among our fellow humans.Ann Druyan, Co-creator of Cosmos; member of NASA’s Voyager Interstellar Message Project; wife of Carl Sagan From a Nat Geo AMA on Tuesday, on Reddit

Did a friend forward this newsletter?

On Thursday, Rachael Bale covers the latest in animal news. If you’re not a subscriber, sign up here to also get Whitney Johnson on photography, Debra Adams Simmons on history, and George Stone on travel.

The last glimpse

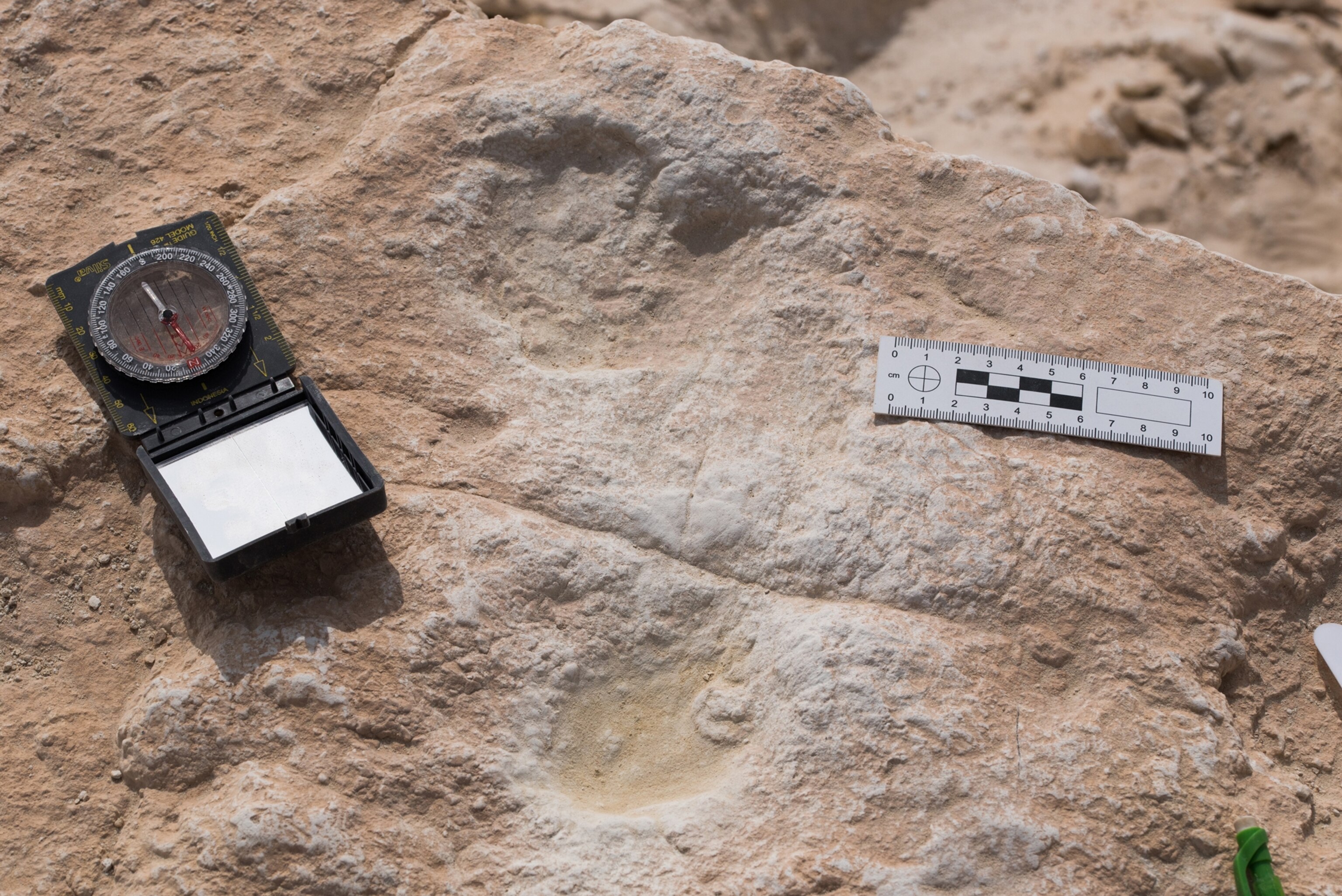

Oldest footprints: What were our ancestors doing walking around what’s now northern Saudi Arabia 115,000 years ago? And what’s with the animal footprints nearby, alongside a shallow lake? If confirmed, these fossil footprints would be the earliest evidence of humans in the Arabian Peninsula, a gateway to early humans’ spread around the world. “The frozen footfalls preserve a striking snapshot of time,” Maya Wei-Haas writes for Nat Geo.