How will this pandemic disrupt science?

By Victoria Jaggard, SCIENCE Executive Editor

Being curious is one of the defining traits of a scientist. It helps to be smart, persistent, and of course well-funded. But it’s that spark of curiosity that really drives some of the most creative discoveries across the scientific landscape. Case in point: I learned this week that we can thank a curious microbiologist and his visit to Yellowstone National Park for the coronavirus tests that are so urgently needed during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Back in the 1960s, Thomas Brock was exploring the park when he noticed a bunch of colorful, stringy mats of microbes in and around the hot springs (above). His interest piqued, he took some samples back to the lab, and the results changed medical science forever, Maya Wei-Haas reports for Nat Geo. Brock discovered extreme bacteria in those mats that produce heat-resistant enzymes, which other scientists then used to improve a process known as PCR—a key ingredient in viral tests, such as the ones used to track COVID-19.

At the time, Brock had just wanted to know how those hot springs and their slimy mats worked. But without his fundamental discovery, who knows when or if PCR would have become as fast and efficient as it is today. Science abounds with stories like these, in which curious people ask basic questions just for the sake of asking, and the answers can often lead to useful applications.

Unfortunately, this kind of basic science frequently comes under attack. In 2017, politicians ridiculed a scientist for studying shrimp running on treadmills. It makes a great punchline, but the experiments served a valuable purpose: the scientist’s work helped show why the animals, farmed for food, didn’t seem to be doing well in their aquatic pens, Sid Perkins reports for Science News for Students.

Basic science now faces a more immediate threat, as the pandemic shuts down fieldwork and redirects equipment and funding. With the disease disrupting so many facets of life, it’s tough to get worked up about postponed missions to Mars or canceled dinosaur digs. Still, when the worst has passed, we’ll have to take stock of the basic scientific advances we lost, and wonder about the future breakthroughs that will be delayed—or never achieved.

Do you get this daily? If not, sign up here or forward to a friend.

Your Instagram photo of the day

Careful! A venomous scorpion glows under blue ultraviolet lights and a red headlamp inside a national park in central Vietnam. Collecting venom samples from around the world, biomedical scientist Zoltan Takacs hopes to identify new pain medications that would serve as good alternatives to highly addictive opioids. Venom already led to one notable success when scientists derived a drug for chronic pain from another of the world’s deadliest animals: the cone snail.

Subscriber exclusive: Photographing a world of pain

Are you one of our 133 million Instagram followers? (If not, follow us now.)

Today in a minute

Food waste: Hoarding and increased cooking at home have caused rises in tossed-out food scraps from homes in big cities—and food experts advise stocked-up Americans to preserve the food they have, remembering that most is good beyond the “best buy” date. The disruption from the coronavirus pandemic extends to food pantries, where volunteers have melted away, food from restaurants is drying up, and the hungry cannot congregate because of social distancing rules. Laid-off workers, taxi drivers, DoorDash, and National Guard soldiers may form assemblers and drivers to get the food to the hungry, Elizabeth Royte reports for Nat Geo.

Inevitable: That’s what Carrie Arnold writes about the U.S. breakdown and delays in testing for the coronavirus. Chronic underfunding and a crucial laboratory mistake are the big reasons cited for the delay. “Those CDC errors have exposed other shortcomings in the nation's capacity for diagnostic testing that existed years before the novel coronavirus emerged,” Arnold reports for Nat Geo.

The brunt of climate change: In the latest magazine issue of National Geographic, we’ve looked at the places where temperatures are rising and falling the fastest as the Earth’s climate changes. Many of the impacts of future warming will be felt by the growing population of city dwellers. Subscribers can read and see the map here.

Time on his hands: A self-quarantining astrophysicist was cruising on a new invention—a necklace that would, he hoped, keep people from touching their faces during this pandemic. It depended on these small, very powerful magnets. Things did not go as planned. “I clipped them to my earlobes and then clipped them to my nostril and things went downhill pretty quickly when I clipped the magnets to my other nostril,” researcher Daniel Reardon told Guardian Australia. He had to be taken to the hospital to have the magnets removed. “Needless to say,” Reardon concluded, “I’m not going to play with the magnets anymore."

This week in the night sky

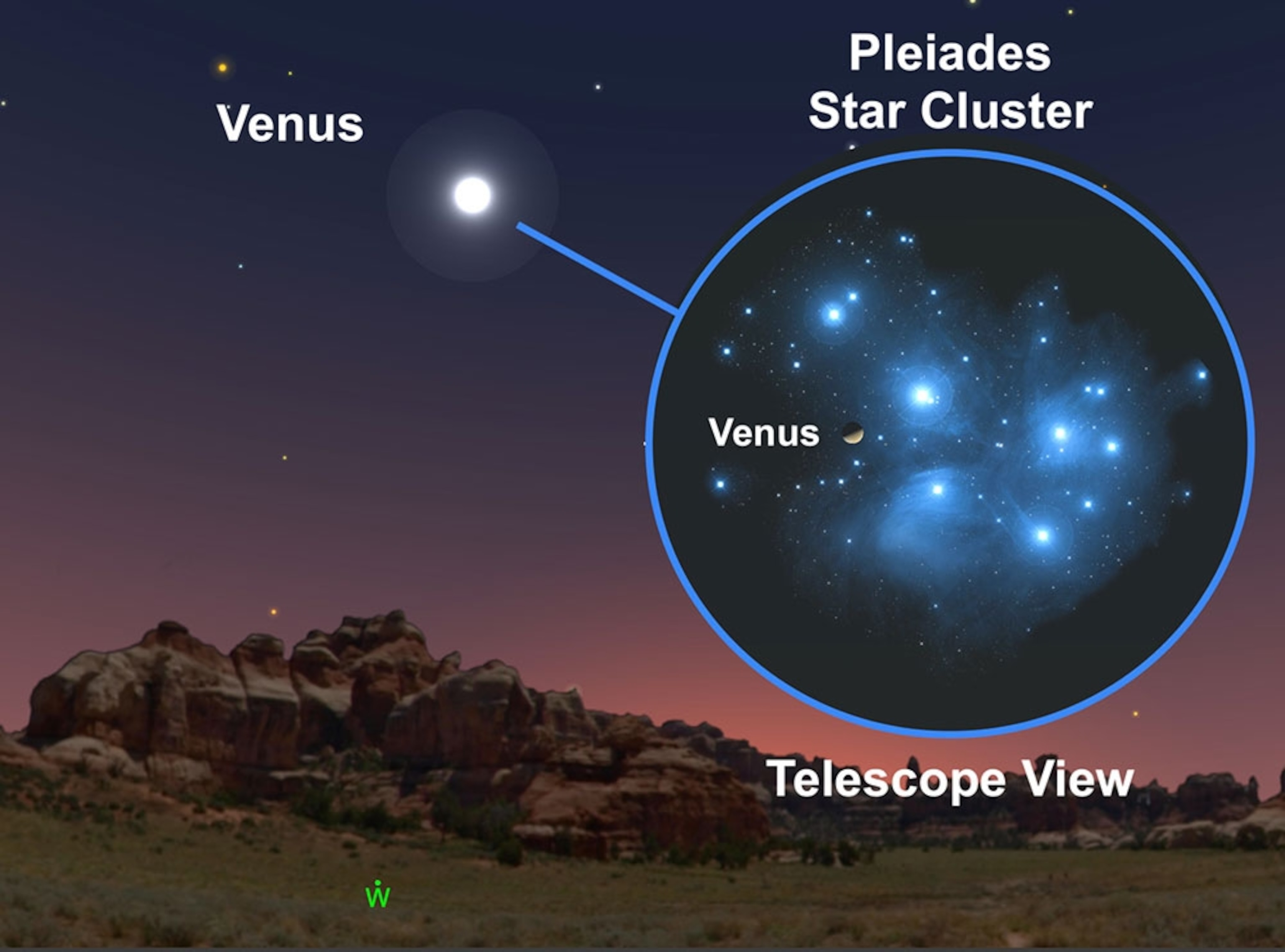

Seven Sisters join Venus: About half an hour after sunset tonight, tomorrow, and Friday, look westward for Venus gliding by the bright Pleiades star cluster. Also known as the Seven Sisters, the Pleiades grouping sits about 360 light-years away and looks like a dipper-shaped pattern of stars. For three nights only, skywatchers worldwide can watch Venus barnstorm the cluster; the bright planet will appear to be only a quarter of a degree away from the cluster in the sky—a separation equal to about half of the full moon’s disk. While close meetings of Venus and the Pleiades happen on average every year, this year Venus will edge especially close. The last time we had such a great encounter was back in 2012, and we won’t see it this impressive again until 2028. —Andrew Fazekas

How are you handling the quarentine?

Making the most of it: From the United States to Ireland, Argentina, and South Africa, Nat Geo readers report they are keeping busy in a host of creative ways, from bottle-feeding calves (here’s one of them) to saving tortoises to setting up times for extended family games or dinners (via Facetime or Zoom). Others say they are cherishing small things: the way that light falls on oranges, the gift of a can of beans, the image of a birthday cake baked by grandchildren far away. Coretta Marshall writes that her aunt sent her a text that reads: “We can celebrate anytime. We just need to remember to be thankful that we are alive.” Many are not sugarcoating the loneliness and fear. Reader Mike Bloodworth said the self-quarantine has turned him from hermit to extrovert. One day, “my neighbor ... suggested we all come outside to catch up. We met at the corner. We all maintained proper social distancing. I jokingly said it looked like we were square dancing. We were only there for about 15-20 minutes, but it really helped relieve the caged-up feeling."

Did a friend forward this to you?

On Thursday, Rachael Bale covers the latest in animal news. If you’re not a subscriber, sign up here to also get Whitney Johnson on photography, Debra Adams Simmons on history, and George Stone on travel.

The last glimpse

Perspective: It’s easy to think right now that everything is falling apart. Despite the global pandemic, other aspects of life are much better than they were during the first Earth Day, 50 years ago. People have much more to eat, are generally living longer, attend school longer, and have less lead in their bloodstreams, writes author Charles C. Mann for Nat Geo. He concludes that people can solve environmental problems, like air and water pollution, if those issues have immediate, tangible effects on humans’ physical welfare. “But the problems we face today are much more long-term and abstract, if no less serious,” he cautions. “They are not, for the most part, like what we have faced before.”

Subscriber exclusive: Globally, the world, even now, is better off than it was during the first Earth Day