Who else is fighting for the Earth's future?

By Victoria Jaggard, SCIENCE Executive Editor

I’ve never been what you’d call an outdoors enthusiast. My idea of fun has always involved being inside, reading a book or playing a video game or scripting my own musical variety show. My friends have often heard me say, I want to save the environment, I just don’t want to be out in it. But even sitting indoors, I know the air I breathe and the water I drink are as safe as they are thanks in large part to the activists behind the first Earth Day.

In 1970, about 20 million people marched across the U.S. to urge action on environmental protections. Within a few short years, we had the Clean Air Act (1970), the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974), and a brand new federal agency called the EPA dedicated to keeping pollution and waste in check. In the decades since, environmental activists have spurred efforts to reduce harmful pesticides such as DDT, phase out lead in gasoline, and provide protections for endangered species and vital habitats. All this activity means that I inherited a better world than the version that existed just a decade before me.

Fifty years after the first Earth Day, young activists are still lifting their voices as the world grapples with what may be its most existential crisis: climate change. Last year, youth activists took to the streets to stage sweeping protests, demanding international action on reducing carbon emissions and reliance on fossil fuels. Like those who marched in 1970, these young people have grown up immersed in the consequences of inaction. “They have seen it for themselves. They have seen the fires. They have seen the storms,” psychiatrist Lise Van Susteren recently told National Geographic. “They’re not stupid, and they are angry.”

“Kids get it,” agreed climate activist Delaney Reynolds, pictured above standing in chest-high water to demonstrate the dangers rising sea levels pose to her home state of Florida.

With much of the world staying home due to COVID-19, it’s easy for some of us to set aside such worries and focus on the immediate threat. This week, headlines abound about the falling price of oil due to the pandemic and federal promises of financial aid to the industry (even as we mark the 10-year anniversary of the biggest oil spill in U.S. history). Bans on single-use plastics enacted in the past couple years are being lifted to keep people safe from the virus, and environmentalists worry these reversals may stay in place. Right now, of course, keeping people healthy and safe is the priority. But I can only hope that the voices championing climate action will still be here after the coronavirus comes under control, reminding us all of the long-range perils we face if we don’t also protect the planet.

Do you get this daily? If not, sign up here or forward to a friend.

Your Instagram photo of the day

Before it melts: Photographer Robbie Shone has explored the world’s glaciers for years. Here, Shone captures a glaciologist descending a moulin (glacier cave) on the Gorner glacier in Switzerland in search of answers to their questions about climate change.

Subscriber exclusive: What happens when the roof of the world melts.

Are you one of our 134 million Instagram followers? (If not, follow us now.)

Today in a minute

How far? Micro droplets spewed out with a sneeze can travel as far as 27 feet, an MIT researcher determined. That finding has big implications for social distancing in this time, since it suggests germs droplets can fly outward at a hundred miles an hour and linger in the air for minutes, researcher Lydia Bourouiba says. “That has implications for how many people you can put in a space,” she tells Nat Geo’s Sarah Gibbens. The accompanying images from the research are fascinating, scary, and a little gross.

How fast? Federal health officials estimated early this month that more than 300,000 Americans could die from COVID-19 if all social distancing measures are abandoned, and later estimates pushed the possible death toll even higher, according to documents obtained by the Center for Public Integrity. Some outside experts say even that grim outlook may be too optimistic.

Already vulnerable: People battling opioids and other drugs find themselves more isolated and with limited access to addiction management tools during the COVID-19 pandemic, writes Lois Parshley for Nat Geo. For instance, care facilities are strained as social and health-care workers themselves are getting sick. “The people who are already the most vulnerable are made even more vulnerable in a pandemic,” says Corey Davis, a public health lawyer at the Network for Public Health Law.

Okay, Einstein: Astronomers are fascinated with a star that, every 16 years, dances with oblivion as it swings frightfully close to a monster black hole. Its fraught orbit, Einstein had said, allowed this star to experience the full strangeness of the universe. Now, after 27 years of close observation, astronomers can say the star is indeed experiencing strangeness. For one thing, the New York Times reports, the star’s egg-shaped orbit does not stay fixed in space, and instead loops around the black hole like a spirograph drawing.

Shakin’: Plate tectonics has sculpted the landscape as we know it today, building mountains, carving out basins, and driving volcanic eruptions. Now, researchers have found what may be the earliest direct evidence for the movement of tectonic plates, Nat Geo reports. By studying the magnetic signatures of a bulbous mound of rusty red rocks in Australia, researchers show the landscape was making a sedate trek roughly 3.2 billion years ago—more than 400 million years older than previous records of such geologic movement.

This week in the night sky

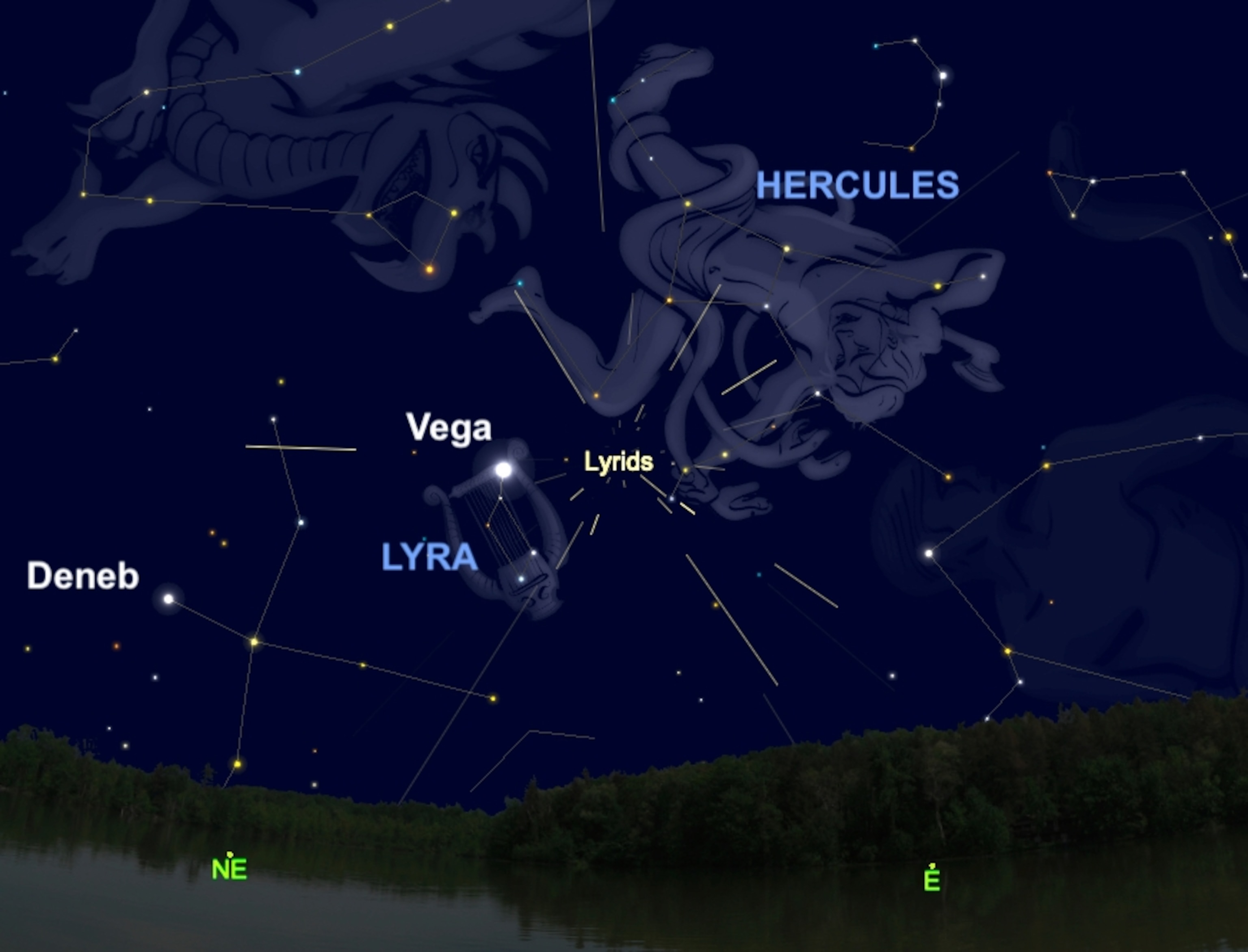

Heavenly harp meteor shower: Tonight, sky-watchers can enjoy the annual Lyrid meteor shower, named after the constellation Lyra, the harp. With the moon out of the overnight sky, dark conditions should let observers see anywhere from 10 to 25 shooting stars an hour, depending on if you view the celestial fireworks from a city suburb or dark countryside. The Lyrids are also known to have surprise outbursts, such as in 1982, when as many as 250 meteors raced by in a single hour. Individual meteors will appear to radiate from the region around the star Vega, which currently shines nearly overhead just before dawn. On Sunday, don’t miss a sunset meeting between the crescent moon and super-bright Venus.—Andrew Fazekas

The big takeaway

Victories, too: News reports these days focus, with reason, on moves to relax provisions on clean air, clean water, and restricting dangerous chemicals. However, here is a list of 50 environmental victories in the half century since Earth Day began. They include saving the ozone layer, successfully breeding California condors and black-footed ferrets, switching to biodegradable packaging, and developing hybrid and electric cars. Above, natural light infuses Virginia’s Manassas Park Elementary, one of the most sustainably designed schools in the country.

Related: A decade later, we still don’t know the full effects from the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico

In a few words

Into the woods you go again,

You have to every now and then.

Into the woods, no telling when,

Be ready for the journey.Stephen Sondheim, American lyricist, from “Children Will Listen"

Did a friend forward this newsletter?

On Thursday, Rachael Bale covers the latest in animal news. If you’re not a subscriber, sign up here to also get Whitney Johnson on photography, Debra Adams Simmons on history, and George Stone on travel.

The last glimpse

The case for optimism: Writer Emma Marris believes that when the 100th Earth Day rolls around a half century from today, we will have a better world. What gives her hope? “We already have the knowledge and technology we need to feed a larger population, provide energy for all, begin to reverse climate change, and prevent most extinctions,” she writes in an Earth Day essay. Pictured above, a diver harvests tomatoes from an experimental underwater farm where plants grow without soil or pesticides.

Subscriber exclusive: Why we’ll save the planet from climate change