Will every hurricane season be like this?

By Victoria Jaggard, SCIENCE executive editor

As I type these words, I’m sitting in a hotel in Corpus Christi, Texas, perched on the western rim of the U.S. Gulf Coast. It’s overcast but warm and peaceful outside, the air stirred only by the ocean breeze that is part of daily life along the coast. About 550 miles away, though, the Gulf city of New Orleans is bracing for yet another round of much rougher weather as Hurricane Zeta makes its way to landfall in southeastern Louisiana.

Zeta is now the 27th named storm in a record-setting Atlantic hurricane season—one so busy the National Hurricane Center ran out of traditional names and had to start using letters of the Greek alphabet. Zeta already came ashore as a hurricane in Mexico, crossing the tip of the Yucatán Peninsula with winds blustering as high as 80 miles an hour. It has gained strength as it has churned northward over the warm waters of the Gulf. If the forecasts are accurate, it could become the fifth named storm to smack into Louisiana just this year. (Pictured above, a Louisiana couple wades through flood waters toward their home after Hurricane Laura).

There is some comfort to be had in the fact that hurricane forecasting has become incredibly accurate. As Alejandra Borunda reports for Nat Geo, storm tracking is currently state of the art, with finely tuned models crunching a wealth of high-quality data streaming in from satellites and airplanes. Some meteorologists even think we may be approaching the limits of how good our storm predictions can be, though that idea remains open to debate.

Still, being able to see storms coming doesn’t change the fact that this hurricane season has been—as predicted—more intense than average, with devastating consequences. We’ve already seen how this year’s stronger, slower storms contributed to erosion of valuable wetlands and extensively damaged coastal cities and towns. At least one of this summer’s hurricanes has now also been tied to the spread of invasive species, Rebecca Renner reports, as rising floodwaters from Hurricane Isaias carried more than a hundred aquatic species into non-native habitats.

Hurricane season is winding down for this year, though there’s always a chance more named storms will appear before (or after) the official November 30 cutoff. If another storm does materialize, we’ll officially break the record for number of named storms in a single season, passing the storm-stuffed year that was 2005. And if climate change continues unabated, scientists predict that more intense hurricane seasons like this one are on the horizon.

Do you get this daily? If not, sign up here or forward to a friend.

Today in a minute

This just in: Germany, Europe's largest economy, has just announced it will impose a one-month partial shutdown in hopes of halting a dramatic resurgence of COVID-19, Bloomberg News reports. The restrictions are the strongest since Angela Merkel's government placed the nation on lockdown in the spring.

Twenty years (continuously) in space: It orbits 254 miles above Earth’s surface, moving at 17,000 miles an hour. Since Halloween 2000, 241 astronauts have called the International Space Station home, some for nearly a full year at a time. “It’s pretty crazy,” retired NASA astronaut Scott Kelly tells Nat Geo’s Michael Greshko. “I’m surprised we haven’t, like, really seriously hurt anybody.” Kelly, who spent 499 days aboard the ISS, says the astronauts, from whatever country, operate as citizens of the Earth. “We’re all in the thing called humanity together.”

Dear Greta Thunberg: Nat Geo’s Oliver Whang yesterday asked the teen climate change advocate what she would tell Americans, who are heading into an election, facing a U.S. pullout from the Paris conference effective Wednesday, and who may not care. “Nothing,” Thunberg responded. Nothing? On Zoom from Sweden, she explained: “If they don’t listen to and understand and accept the science, then there’s really nothing that I can do. There’s something much deeper that needs to change them.” What’s deeper? Thunberg said some people “have stopped caring for each other in a way. We have stopped thinking long-term and sustainable. And that’s something that goes much deeper than just climate crisis deniers.” Here’s the full Q&A. A new documentary on her life, I Am Greta, begins streaming on November 13 on Hulu.

The cost of air pollution: Seventy-two years ago yesterday, a temperature inversion led to five days of “killer smog” in the western Pennsylvania mill town of Donora. By the time it blew away, it had killed at least 20 townspeople and sickened thousands more. “It was not until the tragic impact of Donora,” then U.S. Surgeon General Leonard Scheele wrote, “that the Nation as a whole became aware that there might be a serious danger to health from air contaminants.” Nat Geo’s Cynthia Gorney tracked down an 88-year-old survivor, who told her: “We all knew the air was bad. But we thought that was a way of life. We didn’t realize it was going to kill people.” Read more here.

What makes a superspreader? For some people, it could be the shape of one’s body. For others, it might be loud talking or breathing fast. Researchers examining what type of person spreads COVID-19 most widely are zeroing in on common denominators, Fedor Kossakovski reports for Nat Geo. “They’re not sneezing. They’re not coughing. They’re just breathing and talking,” says Donald Milton, an aerosol transmission expert from the University of Maryland. “They might be shouting. They might be singing. Karaoke bars have been a big source of superspreading events. We saw one at a spin cycle club up in Hamilton, Ontario, where people are breathing hard.” Read more here.

Instagram photo of the day

Florida’s limestone filter: Cave diver Joseph Seda surfaces from one of Florida’s hundreds of cave springs during a late-afternoon downpour. Rain that isn’t evaporated or used by plants soaks into the aquifer and is naturally filtered by slow flow through Florida’s porous limestone. Rain falling in some parts of the state will flow underground for decades before bubbling to the surface through one of the cave springs.

Related: Mesmerizing photos reveal hidden world of Florida’s underwater caves

The night skies

Blue moon haunts Halloween skies: Little ghouls and goblins heading out on this spooky Halloween Night will get a creepy bonus: a full moon rising about a half hour after sunset. Not since 1944 have we had this holiday coinciding with a full moon. It’s actually a blue moon, the name for the second full moon of a calendar month. While normally the moon shines with a cold, silvery glow, some observers across North America downwind from the West Coast fires may witness a blue-tinged moon due to tiny smoke particles refracting the moonlight. Halloween night also will feature a super-bright Mars as well as the planet Uranus, which reaches its brightest on the scariest night of the year, a distinctly green-colored dot just above the full moon. (Pictured above, a blue moon in July 2015.) —Andrew Fazekas

The big takeaway

Colorado wildfires: While horrific blazes in California and Oregon have gotten much of the media’s attention, Colorado has recorded its two biggest wildfires this season and has seen 1,100 square miles charred—a third of that in October, outside the normal fire season. Last month, it looked like the city of Boulder, just named America’s best place to live by U.S. News and World Report, would be threatened by a fast-moving wildfire. “For only the second time in the 18 years I’ve lived here, on the southwestern side of town, my family packed go bags,” Hillary Rosner writes for Nat Geo. Rosner reflected the view of many in the West who had thought over the years that they were safe from fires. (Pictured above, pyrocumulus clouds from the East Troublesome Fire rise above Coal Creek Canyon in Colorado last Wednesday—just before the fire crossed the Continental Divide.)

In a few words

Montana is wondrous, though not for everybody. ... I came in 1973, for the trout fishing, and I’ve stayed for the snow and the cold and the bracing Scandinavian gloom.David Quammen, Writer, on his adopted state; from America The Beautiful: A Story in Photographs

Did a friend forward this newsletter?

On Thursday, Rachael Bale covers the latest in animal news. If you’re not a subscriber, sign up here to also get Whitney Johnson on photography, Debra Adams Simmons on history, and George Stone on travel.

The last glimpse

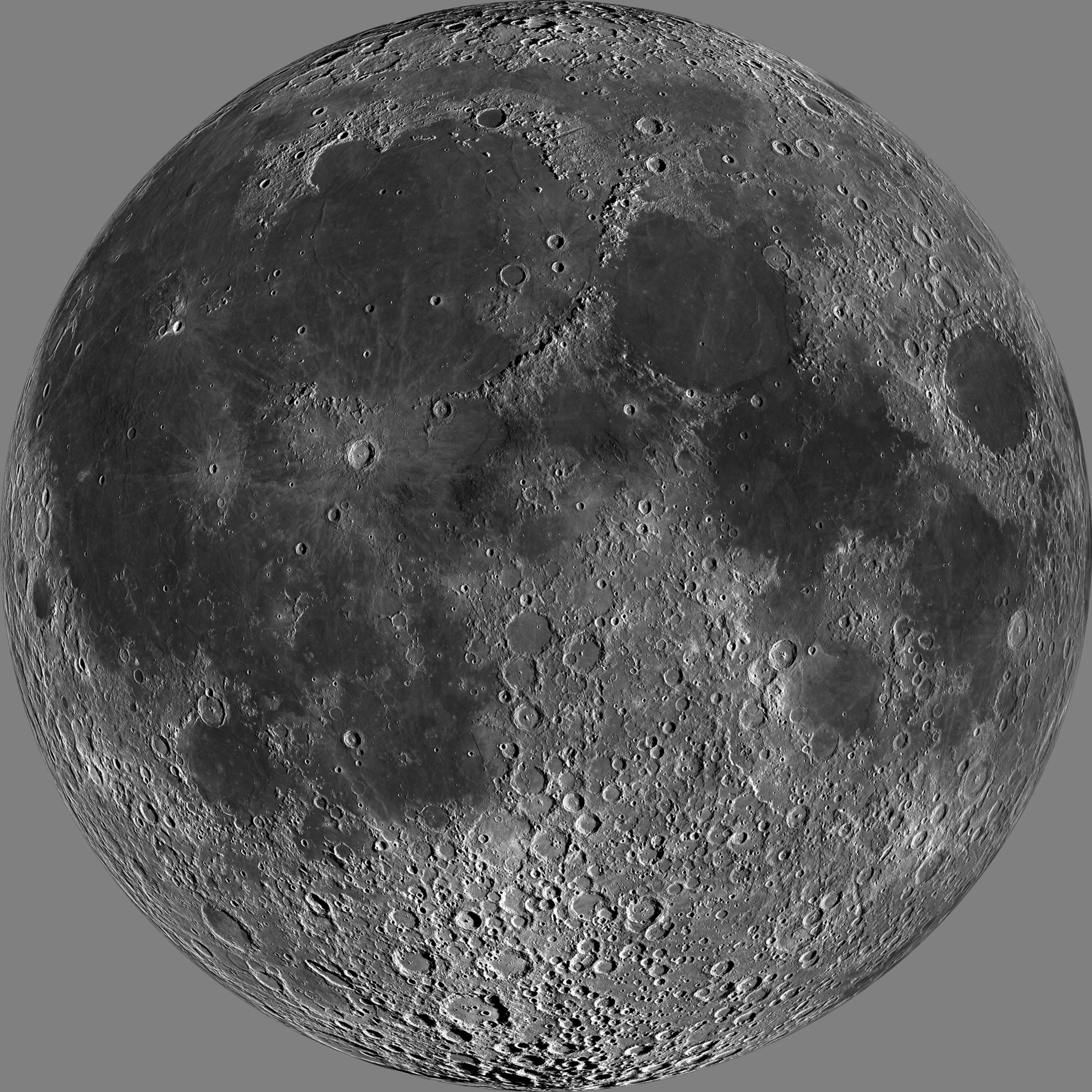

A liquid lunar mystery: Where and how much water can linger on the Moon? Two new studies answer: a) water can exist on a much broader chunk of the lunar surface than we previously thought; and b) we dunno. “The exact movements of this water, and possible transfer from sunny to shadowy zones, remain mysterious,” Jessica Sunshine, a planetary scientist at the University of Maryland, tells Nat Geo’s Maya Wei-Haas. This work is also vital for future humans traveling to the moon and beyond, perhaps allowing humans to convert water to fuel.