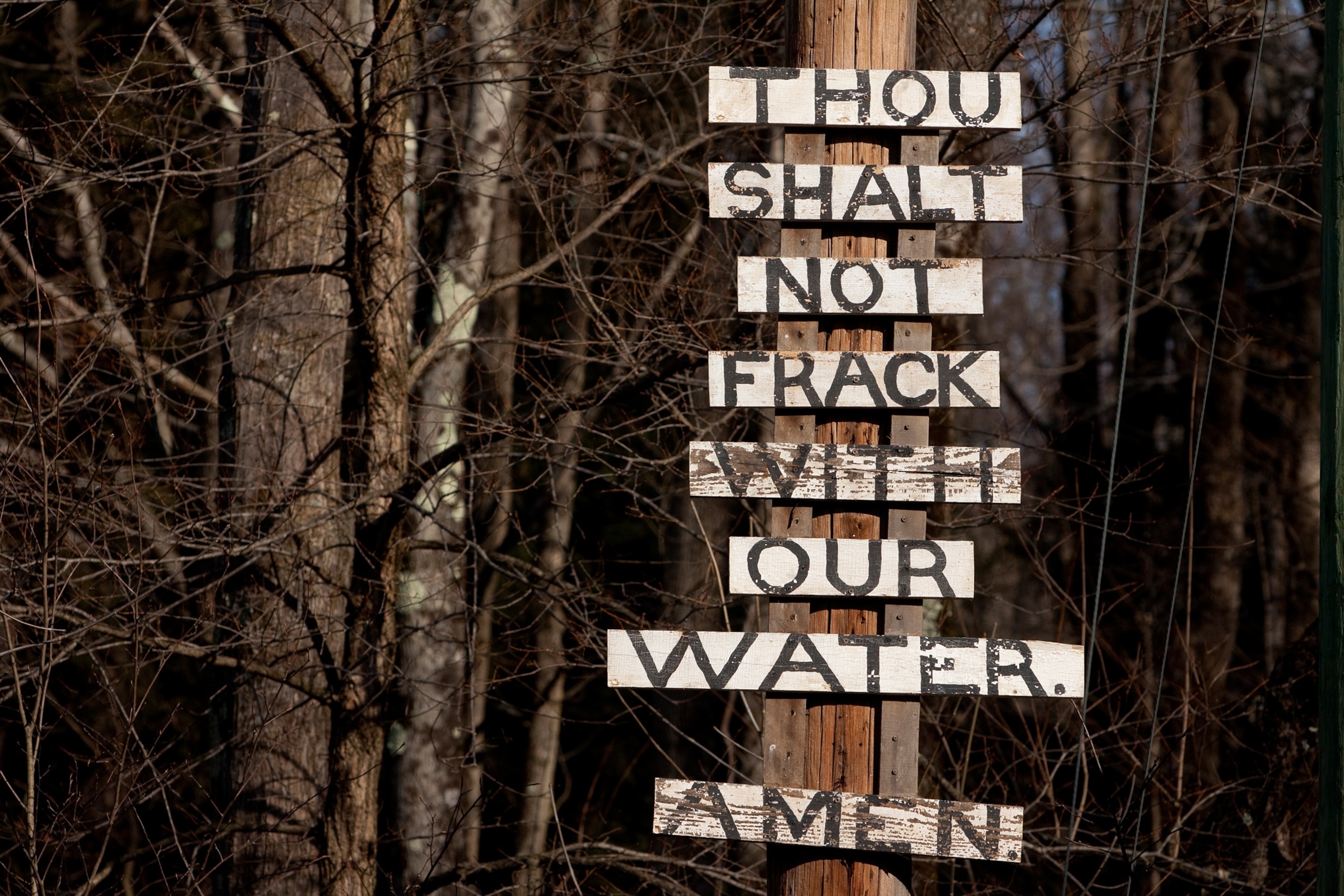

Could New York's Fracking Ban Have Domino Effect?

Activists hope the Empire State's decision will help end drilling in other states.

New York's decision to ban fracking for health reasons could reverberate beyond the state, bolstering other efforts to limit the controversial method of drilling for oil and natural gas.

While two dozen U.S. municipalities and at least two countries, Bulgaria and France, have also adopted bans, states have been slower to act. Fracking opponents say New York, which surprised them Wednesday with the boldest move of any state so far, will change that.

"It definitely has a national political impact ... It really has a domino effect," says Deb Nardone, director of the Sierra Club's Keeping Dirty Fuels in the Ground initiative.

She and other activists say the measure could intensify pressure to roll back nascent fracking plans in California, Illinois, Maryland, and North Carolina, and to help secure a permanent ban in the Delaware River Basin, which supplies drinking water for nearly a thousand community water systems in the mid-Atlantic region. It could also buoy efforts in various state legislatures, many of which return for a new session in January.

Boon or Bust?

The anti-fracking campaign still faces stiff odds. Fracking—aka hydraulic fracturing—has fueled a U.S. energy boom and revived the economies of some states, such as North Dakota, and many communities.

Yet studies have found groundwater contamination and air pollution near fracking sites, increasing the risk of cancer, birth defects, skin rashes, and upper respiratory problems.

Fracking, combined with horizontal drilling, blasts chemical-laced water mixed with sand underground to break apart shale rock and extract oil and gas. Some of the fluid may leach into groundwater. (See related interactive: "Breaking Fuel From the Rock.")

Still, industry groups remain ready to fight.

"We look forward to continuing to work with landowners and our labor allies, who are focused on creating jobs," said Karen Moreau, head of the New York council of the American Petroleum Institute. She called New York's decision a "missed opportunity to share in the American energy renaissance."

The oil and gas industry has already challenged bans, sometimes successfully, in court.

Last month, an industry group filed a lawsuit just hours after Denton, Texas—which sits atop the gas-rich Barnett Shale—adopted the Lone Star State's first fracking ban. Voters in three other U.S. municipalities also approved fracking bans in the midterm elections. (See related story: "As U.S. Fracking Bans Increase, So Do Lawsuits.")

Follow the Leader

But New York could be a turning point.

"We're seeing advocates in other states latching on to what New York has done in support of their own efforts," says Kate Sinding, senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group.

Health and environmental groups immediately called on Maryland's outgoing Democratic governor, Martin O'Malley, to follow New York's lead and reconsider his recent decision to allow fracking if safeguards are met. O'Malley has put forward regulations, but his GOP successor, Governor-elect Larry Hogan, may fight them. Hogan sees fracking in western Maryland as an "economic gold mine."

Sinding says New York, which had a fracking moratorium in place since 2008, is not the first state to halt the drilling practice. But its decision is the most significant.

New Jersey approved a one-year fracking moratorium that was lifted in 2013, and North Carolina is moving to end its own moratorium. Connecticut has a moratorium on accepting fracking wastewater from other states. And Vermont's governor signed a law in 2012 imposing a long-term moratorium on the practice (a largely symbolic act, given that Vermont has few shale resources).

New York's ban, by contrast, could have a huge economic impact. The state is home to part of the Marcellus and Utica shale formations that have yielded an energy bonanza in neighboring Pennsylvania.

New York's acting health commissioner, Howard Zucker, said the state's new examination found "significant" public-health risks associated with fracking because of drinking-water contamination and increased air pollutants such as diesel and volatile organic compounds.

"The potential risks are too great," he says. "In fact, they are not even fully known." (See related story: "Health Questions Key to New York Fracking Decisions, but Answers Scarce." )

Hard Science and Public Sentiment

Environmental and health advocates say science is on their side.

"There are enough peer-reviewed studies that show harm to water and health," says Emily Wurth of Food and Water Watch, an environmental group. (See related story: "High Levels of Dangerous Chemicals Found in Air Near Oil and Gas Sites.")

Public sentiment may be shifting as well.

In November, the Pew Research Center found that support for the increased use of fracking in the U.S. has fallen to 41 percent, down from 48 percent in March 2013. In that same time period, says Pew, opposition has risen from 38 percent to 47 percent.

More U.S. municipalities, from coast to coast, have approved fracking bans or temporary moratoriums. In addition to New York—which has 80 bans and 100 moratoriums in place, though some have expired—26 other municipal bans have passed in the United States, says Karen Edelstein of the FracTracker Alliance. (See "Battles Escalate Over Community Efforts to Ban Fracking.")

Money Talks

Even so, the economic benefits of fracking have made it a difficult target, even in typically pro-environment states.

In New Jersey, the legislature twice approved a ban on accepting wastewater from fracking operations in Pennsylvania, but Republican Governor Chris Christie vetoed it. And in California, Democratic Governor Jerry Brown, long hailed as an environmental champion, signed a bill last year that would allow fracking if certain requirements are met.

While the northern California counties of San Benito and Mendocino approved anti-fracking measures in last month's midterm elections, a proposed ban in wealthy Santa Barbara County—where fracking is already occurring—failed after a coalition of energy companies waged a costly opposition campaign.

In May, oil interests also helped defeat a bill in California's senate that would have imposed a moratorium on fracking. Yet anti-fracking lawmakers are expected to make another push next year.

On Twitter: Follow Wendy Koch and get more environment and energy coverage at NatGeoGreen.

The story is part of a special series that explores energy issues. For more, visit The Great Energy Challenge.