How to see the planet from above and below

By capturing the same thing from very different perspectives, a NASA astronaut and an intrepid photographer create a whole new way of seeing our world.

Earlier this year, two photographer friends had just finished shooting the Grand Canyon when they began discussing what they might capture together next. Don Pettit was eager to train his camera on Madagascar and sent his friend Babak Tafreshi a text extolling the beauty of the place.

Tafreshi didn’t disagree: He imagined the famous baobab trees, with their thick trunks and filigreed branches, cast mesmerizingly against a dark, star-speckled sky. So, even though he was tired from a good bit of traveling, he boarded a flight from Boston to Paris, and then another to Antananarivo, Madagascar’s capital city, where he stayed overnight before renting a car and driving out to the remote realm of the baobabs, a dirt road lined with dozens of the ancient trees.

Pettit’s journey was simpler: He floated from one room on the International Space Station to another, toward the windows that looked out onto the world.

During his seven-month mission on the ISS, Pettit—who’s been an astronaut for nearly 30 years—worked with Tafreshi, a photographer and National Geographic Explorer, on an inventive project to photograph the same location or phenomenon from two wildly different perspectives, one photographer standing on the Earth, the other floating 250 miles above it. Together, they coordinated 10 photo shoots across four continents. The result is a celestial scrapbook of our planet, with spellbinding scenes that can make you feel grounded and weightless at the same time.

The pair initially connected not long after Pettit’s first stay on the then newly assembled ISS, in 2003. Pettit, an amateur photographer since sixth grade, had brought his digital cameras with him, and he’d used some scavenged station materials to fashion a camera mount that provided the stillness necessary to capture the night sky without smears of starlight. (Pettit, a scientist by training, is among NASA’s craftiest astronauts; he once designed a drinking cup to make sipping coffee easier in microgravity.) At the time, Tafreshi was working as an editor at the Iranian astronomy magazine Nojum. He had taken up photography as a teenager, focusing on the night sky and the natural wonders that become visible in the absence of light pollution. When Pettit’s pictures reached Earth, Tafreshi emailed the astronaut with compliments. Soon they became pen pals.

Years later, as their correspondence grew into a photo project, Pettit and Tafreshi found that it helps to have different approaches to telling visual stories about Earth. Pettit, in particular, felt a duty to share his orbital vantage point with his fellow humans on Earth. “You want to share that imagery to people that don’t necessarily have the wherewithal to be there in orbit,” Pettit said.

Over the course of their project, the duo sought to synchronize their photo shoots, which required a tremendous amount of planning. They needed to account for orbital mechanics; from his perch on the ISS, Pettit circled the globe every 90 minutes, racing sunrises and sunsets. The trajectory of the space station mattered as well. When the pair first started brainstorming potential areas of interest, Tafreshi had plenty of ideas. “I told him, You know, Iceland is great,” Tafreshi recalled. But the ISS, Pettit replied, never flies over Iceland. Earthly considerations influenced the project too. Pettit once suggested a couple of regions that appeared photogenic from hundreds of miles up, but they were along the borders of countries in conflict—India and Pakistan, and North and South Korea—“so I couldn’t travel there because of safety matters,” Tafreshi said. Pettit, meanwhile, had to work around his astronaut duties. “When you’re on station, you’ve got a pretty encompassing day job,” Pettit, who has logged nearly 600 days in space across four missions, told me. “You need to make sure that there’s a hole in your work schedule where you can run to the cupola and take a few pictures.”

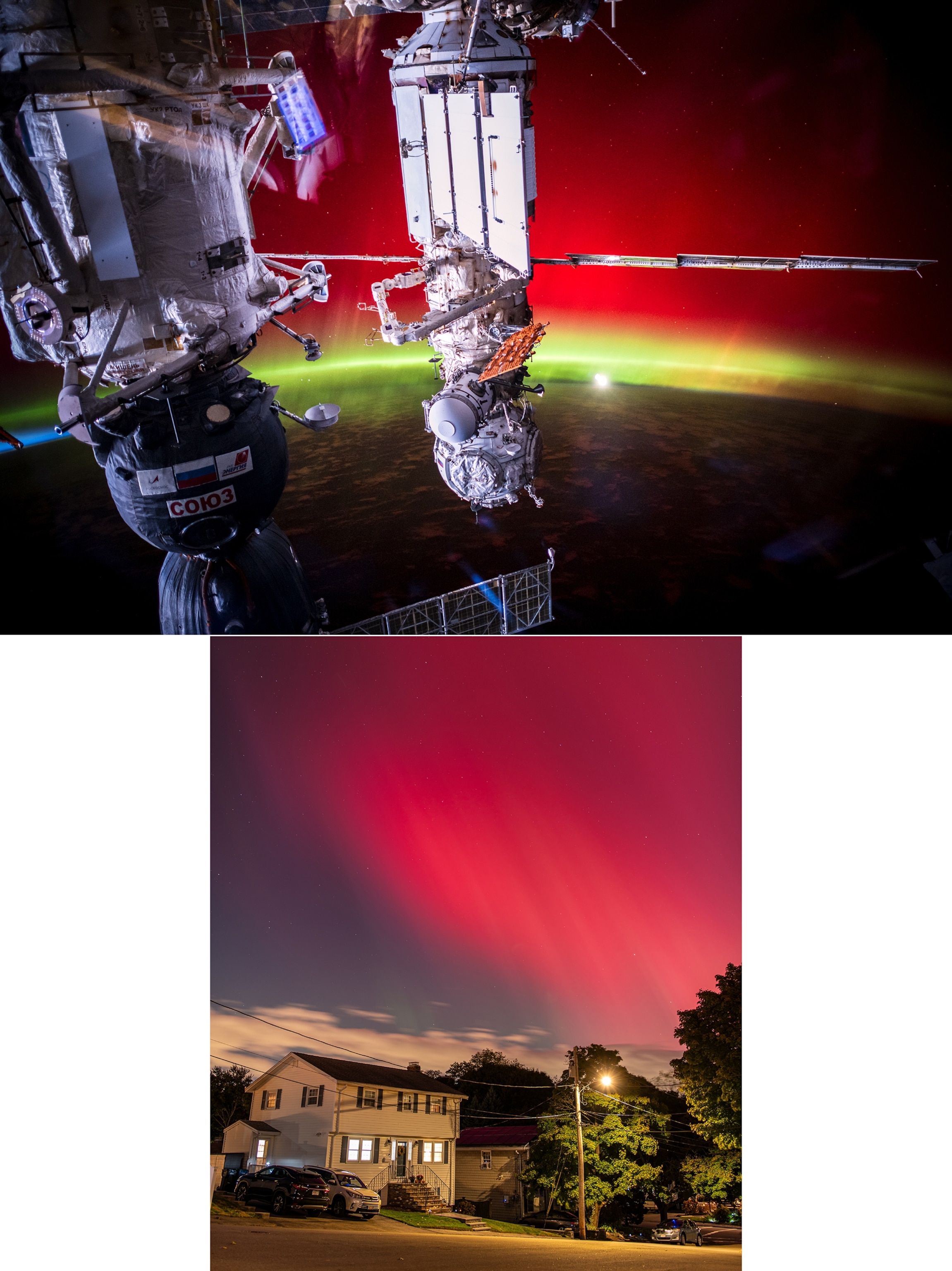

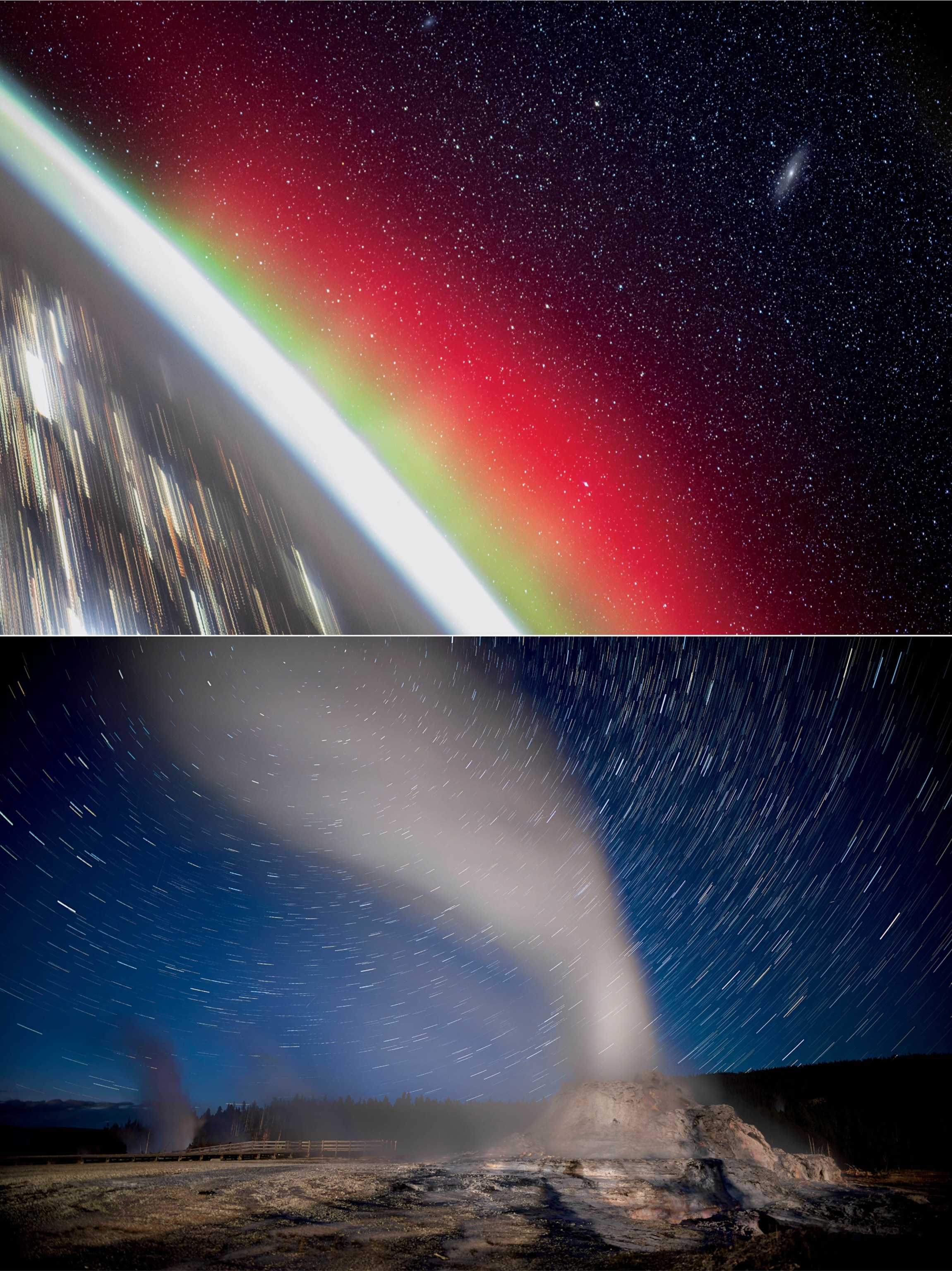

Sometimes the universe went easy on them. A comet, visiting from the edges of the solar system, showed up a week after Pettit reached orbit. Tafreshi observed the bright object in Puerto Rico, but Pettit “had the best view,” without Earth’s hazy atmosphere, with its pesky clouds, in the way. Not long after that, a major aurora storm appeared in the skies over Tafreshi’s house—how convenient!—and the photographers captured the event within hours of each other, their best timing of the entire endeavor. When it comes to the rippling, mystical green lights, two views are better than one. “If you look at the same ripple from orbit, you might find that it’s actually an oval,” Pettit said. It’s as if they had surrounded the shimmering phenomenon, revealing its true nature.

While Pettit was spared the difficulties that can ruin a photographer’s day on the ground—rainy weather, for example—his cameras would occasionally malfunction because of the constant, invisible barrage of cosmic radiation, and now and again artifacts of astronaut life sneaked into his shots. Once, Tafreshi was scanning Pettit’s images of the Maldives, in the Indian Ocean, when he noticed an intriguing patch of green in the water—an algal bloom? “I was so excited until I got the next few shots and I realized, This patch is moving very fast,” Tafreshi said. It turned out to be a weight-lifting machine, reflected in the space station’s windows. “Every crew member works out on this machine for an hour and a half a day,” Pettit said. He would occasionally ask his colleagues if they wouldn’t mind turning off the lights and working out in the dark, just for a few minutes. Not everyone obliged.

Pettit and Tafreshi both believe that space photography is better done by people; there are plenty of satellites that take images of Earth from orbit, but often these pictures are flat and textureless. Pettit can play around with light and shadow, creating a richer portrait. And an orbital view of Earth is more meaningful when there is real emotion behind it. Karen Nyberg, a retired NASA astronaut, told me that she liked photographing the places where she knew her loved ones were. “I would go over Houston, or go over when they were visiting upstate New York, and feel very connected to them because I was only 250 miles away, just directly above them,” Nyberg said. “And then I would actually start to feel kind of this connection with people in other places on the Earth that I don’t know.” There’s also perhaps a hint of triumph in it; human bodies were not made to be in outer space, but there astronauts go, soaking up the wonder and sharing it with the rest of us.

In more than two decades of friendship, Pettit and Tafreshi have met in person only a handful of times. They communicate mostly via text and email. They told me they don’t really talk about their personal lives or get too philosophical, despite the nature of their work; their conversations are the stuff of true shutterbug geekery, all about f-stops and imaging software. Still, they’re not just photography buddies. When Tafreshi was robbed in Sicily and lost most of his equipment, he withheld the depressing details from Pettit because he didn’t want to worry him, explaining to me that it’s best practice not to upset an astronaut far from home. Pettit gently razzed him, saying that Tafreshi should be more careful about where he keeps his passport, which had been stolen too.

The Madagascar shoot was their last session before Pettit returned to Earth. The region has little artificial light, so Pettit’s shot hinged on the very alignment of celestial bodies—the presence of a full moon—to illuminate a landscape shrouded in nighttime. Tafreshi stood in the brush, taking in the shimmer of the Milky Way in the unspoiled sky. “It was surreal,” he said. The evening quiet was punctuated by the nocturnal murmurings of unseen wildlife and of villagers passing by in carts pulled by mules. From above, Earth is a gleaming world with a wispy atmosphere in an inky void. From below, it is a tangle of flora, fauna, and humanity that, as far as we know, doesn’t exist anywhere else. The resulting diptychs present Earth as it truly is—just another planet, and our only home.

Babak Tafreshi, a Boston-based National Geographic Explorer, visited four continents for this story. He is a past winner of the Royal Photographic Society’s Award for Scientific Imaging.

A former Atlantic staff writer, Marina Koren says her beat is “all things space,” including astronomical discoveries and human spaceflight. This assignment reminded her, Koren says, “that the cosmos is a physical place we inhabit.”

Maps: Matthew W. Chwastyk, NGM Staff

Source: NASA Johnson Space Center