An antique process helps this photographer capture coastlines bound by Celtic soul

Alex Boyd's atmospheric images from the wild edges of Scotland and Ireland tell a story of patience, tenacity—and complex human identity with the landscape.

In an essay closing his new book The Point of the Deliverance, photographer Alex Boyd describes the images in its pages as comprising ‘a unique visual record of the Irish and Scottish coastlines experienced through the eyes of an itinerant photographer.’

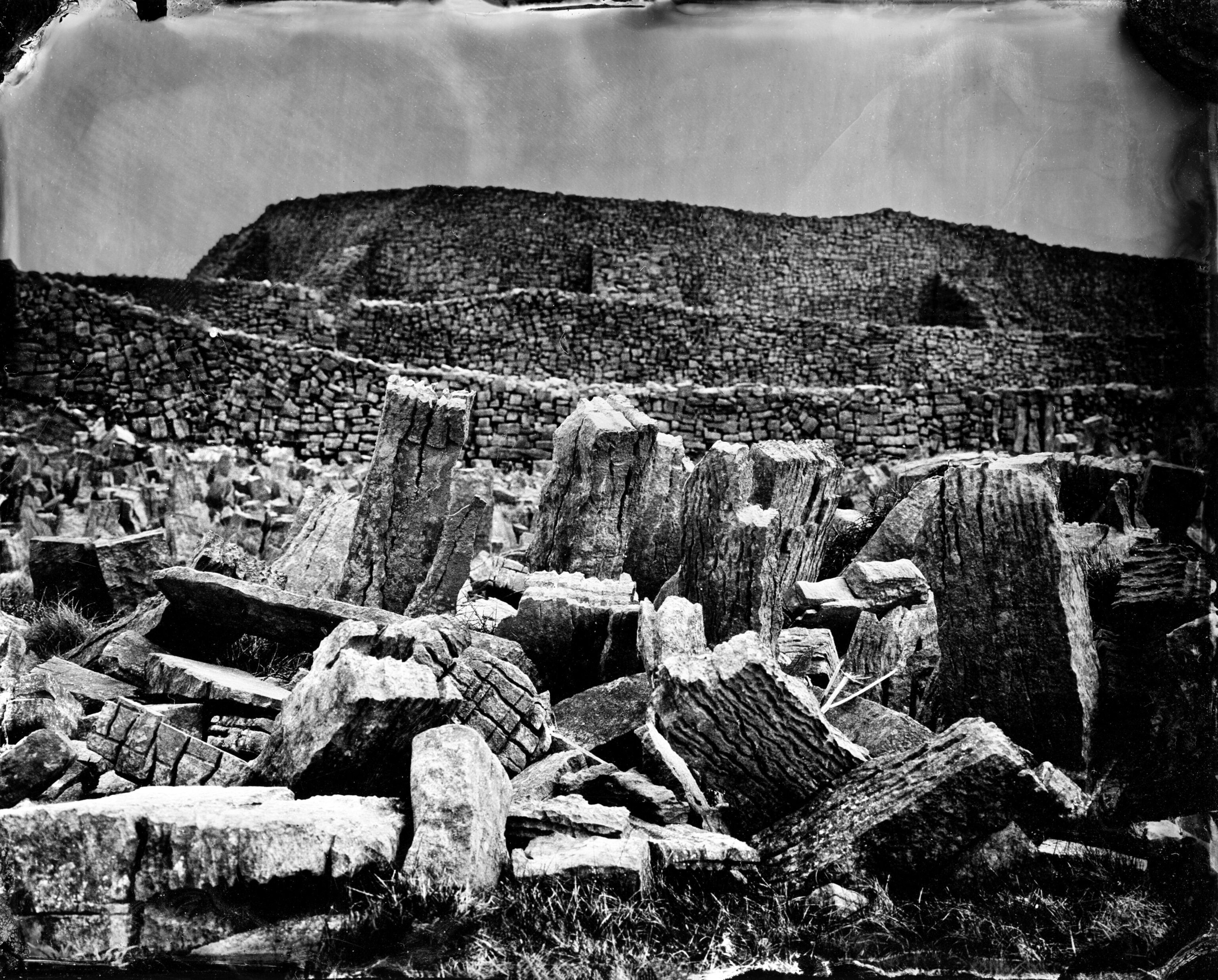

A glance through its hundred pages of black and white imagery and this statement immediately connects, certainly superficially; shadowed mountains, buildings battered by elements and neglect and rough-cut coastlines speak of hard time served on the frayed edges of Britain and Ireland. But there's something else, too: the images themselves look ravaged by the centuries, with corner-curls and fluidic textures, scratches and process darkenings giving each shot its own physicality.

This is no post-process filter: it's the real deal. Boyd, an acclaimed writer and photographer raised on the west coast of Scotland, has been exhibited internationally for his work with antique image processing techniques used by Victorian pioneers. Using plate cameras and in-situ processing, Boyd chose this medium with which to explore familiar territory and the deep themes it evokes—not least the history and identity between the tempestuous coasts the book unites. Here Boyd explains the thinking behind, and the genesis of, his latest work.

What do you see as the connecting lines between Ireland and Scotland as landscapes?

“When I began this project, I had several Scottish locations in mind, many of which would mirror those in Ireland, hopefully creating a visual dialogue. Some shared a geology, the most obvious being the basalt columns of the Giant’s Causeway [in Northern Ireland] with those of Staffa [an island off the coast of Scotland], the mountains of County Cork and those of Skye's Cuillin. The haunted karst landscapes of Ireland's The Burren would find their counterpart in Northern Scotland's Assynt.

“The places which continue to draw me along this coastline are not subtle. They are topographies which often contain a strong vertical dimension, a precipice, an edge. They tower above, they can oppress. They exude an ancient hostility, and appeal to something within me which inspired the imaginations of our ancestors.

“When I think of the Scottish and Irish coastlines that I grew up on, I think of the way that this environment has helped shaped me. From the bitingly cold winter days of harsh winds and battleship grey skies to the more benevolent summer calm and gentle swells. It’s reflected in our temperaments and in our culture.”

So what about that—those historical points of connection. Do these places share a soul?

“When I think of Ireland, I think of Scotland, but a Scotland experienced through the looking glass. That is not to diminish the uniqueness of the island of Ireland, but to emphasise the closeness of our shared cultures. As a child I could look from the highest peak of our local mountain Goat Fell [on Scotland's Isle of Arran] and see the Northern Irish coast of Antrim along the horizon. At its narrowest point, we are a mere 19km apart.

“For me, the soul of a culture exists in the songs and stories of the land and its people. I found this in the poetry of Seamus Heaney and Sorley Maclean, the great Irish and Scottish poets of the 20th century. Their words opened-up entire worlds, bringing the landscape to life. In trying to learn to speak Scottish Gaelic, a language which shares its roots with Irish, maps suddenly became full of new description and meaning. The great sea-lanes which surround [these] islands have seen the exchange of people and stories for millennia, something reflected in our place names and much more.”

Then there is the literal migration, both voluntary and involuntary…

“A constant movement of people between Ulster and the West Coast of Scotland would influence and change both places, a cultural and linguistic bridge across the Irish sea. My own family would be one of those which would make the crossing many times through marriage and migration.

“It is migration which may be one of the most defining ties between our countries, often in the face of hardship. Through Clearances and famine the Irish and Scots have left these islands in search of better lives elsewhere; many of the locations in this project are what remain of their homes. The old beliefs and ways continue to endure, often on the peripheries.”

Tell us about the photographic method you used for this project.

“The images are made using a technique from the early days of photography—wet plate collodion. It was invented in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer, and allowed photographers to make high quality images on glass that were therefore easy to reproduce in equally high quality. It is the process we most associate with the Wild West and of the America Civil War, and of our own early depictions of the landscape. In the 19th century it was revolutionary. Today of course it is anachronistic, and completely impractical.

“Early professional landscape photographers usually worked with a team of people who would help transport, develop and process the photographs on site. Images are made by pouring collodion, a thick syrup-like substance on a piece of glass, and then submerging it in silver in a darkened place such as a dark tent. The silver makes the collodion light sensitive: a photographic film, which can be loaded into the back of a field camera. The film is exposed, and then the image is developed in the dark tent using ferrous sulphate. In the dark of the tent, guided by only a red light, a negative image appears, and is then washed in water.

“Out again in the light of day the image is fixed using cyanide and a positive image appears in a moment which can best be described as pure theatre. It does not always work, but when it does it can feel thrilling.”

You can get a collodion phone filter these days. Why go through all of that? What does the result say about the landscape?

“It was a new challenge. Working this way would force me to spend hours in a location, using a slow and methodical way of producing images to get to know a location more intimately. In collodion the landscape is rendered differently due to the way in which the chemicals ‘see’ the landscape—reds are rendered black, blues as pale whites. This spectral sensitivity is why in many of the images there are cloudless skies, and the northern landscape seem austere, brutal.

“But to make images like the Victorians in the 21st century however was never my intent. I had learned the process, and now it was time to deconstruct it. The smears, freckles, comets and other evidence of working with the process would horrify the photographers of the 19th century, each in the pursuit of perfection. [Mine] would be a record which depicted not only the physical landscapes of Scotland and Ireland, but something else, something other.”

“In collodion the landscape is rendered differently due to the way in which the chemicals ‘see’ the landscape – reds are rendered black, blues as pale whites.”Alex Boyd

“Making glass plates on the Isle of Skye, my home for a year, proved to be the biggest challenge. Working in the strange landscapes of the Quirang and the Old Man of Storr could at times be disorientating, while making images from the peaks of Sgurr na Stri (The Peak of Strife), and the Cuillin mountain range proved to be the biggest physical challenge I had set myself. The final images reflect the exhaustion both physical and mental I felt when creating them. I’m not sure I could make those again today.”

How did you choose your landmarks?

“Like most photographers, the landscapes that I’ve documented as part of The Point of the Deliverance reflect my own interests and concerns.

“The project began in the coastal moorlands of County Mayo in the north west of Ireland, somewhere I knew only through the work of Seamus Heaney. In his poem ‘Belderrig’ he recounted the discovery of artifacts from the Céide Fields, a large featureless peat moorland which stretches from the coast far inland. Beneath the turf an extensive system of prehistoric field systems lay hidden, uncovered through the work of local farmers and archaeologists.

(Read: Soldiers stumbled upon a 2,400-year-old tomb on the battlefields of WWII.)

“The thought of an entire world beneath my feet was a tantalising one, and provided a way in which to access this landscape: through archaeology. It would be the first place I photographed, the moor a great black sea, the mountains like ships beyond.

“I would spend hours examining maps for coastal forts, ancient monuments and other places which once were home to the Iron and Bronze Age people of North Western Europe.

“But despite the Victorian camera, and an abiding interest in archaeology, I wanted to spend time in the present. I’m not a re-enactor, and I’m not interested in producing bucolic landscapes using an old process. I wanted to meaningfully engage with my surroundings, and get to know people who lived in the places I was making images.”

Tell us about the title of the book.

“In Erris, County Mayo, I met up with local writer Vincent McGrath and his wife Treasa to talk about their book ‘The Placenames and Heritage of Dún Caocháin (Kilcommon) in the Barony of Erris’. Working with the local community, they drew together a map of Gaelic placenames from fields to coastal cliffs, recording the experiences of generations of people on the land, and the sea. One of them, The Point of the Deliverance, referred to the place in the bay that currachs [a small wood-framed boat] returning from the sea would reach safe harbour.

“Vincent was also an environmental protestor. As one of the Rossport 5 he had been imprisoned for his part in protesting the Shell Oil Company building a pipeline in his area from the Corrib gas Field offshore. He pointed me in the direction of the now abandoned cottages which served as a visual focal point in the campaign against the oil company. The motto emblazoned on the roof ‘Strength in Community’ is one which recounts those events, but serves as a warning to future generations. To document what happened there felt an important part of the story of the coastline.

(Related: Scotland was once covered by a great, wild forest. Or was it?)

“In particular the remains of empty settlements served as a poignant reminder of communities now lost. Eventually other abandoned structures would find their way into my work, most memorably the wreck of the MV Plassey, a cargo vessel which now sits high on a beach on Inisheer.”

One word that’s often used when discussing these regions amongst others, is ‘Celtic’. What does that word mean to you?

“That’s such a huge question. For me it’s changed over time. When I used to think of ‘Celtic’, the word had an almost negative connotation, it was something romantic, of the past, little to do with the present. At worst I associate it with misplaced sentimentality and problematic notions of ethnicity and nationalism, very much contemporary issues. It can be a polarising term.

“My definition of being Celtic is one which is very much rooted in the present. Yes, there are the geographic and linguistic regions which we associate with the Celtic world, from Scotland and Ireland to Wales, Cornwall and Bretagne in France. There is also the diaspora spread across the world, from America to Australia. Each carries within them their own definition. I speak only for myself.

“It’s about being informed by the past and your traditions, but looking to the future with these in your heart. It’s about accepting people and respecting their experiences. It’s acknowledging the words of Patrick Geddes when he said ‘By Leaves We Live’. It’s a living breathing culture. It’s the quiet desperation of growing up with my friends in a harbour town: Cuimhnichibh air na daoine bho'n d'thainig sibh (remember the people whom you come from). It’s the singer and tradition bearer Mary Ann Kennedy, it’s Murdo Macdonald helping to tell the story of Celtic Art, its Roddy Murray the writer on Lewis, its Gerry Cambridge's poetry, it’s the work of the artist Anne Campbell walking the moors. It’s in sharing stories with my daughter, and teaching her songs in Scots and Gaelic. It’s all of this and yet it’s so much more besides.

“Do my images depict the Celtic world? Perhaps only one small aspect of it. The places I photograph are largely empty of people, or they have been emptied. Many are memorials, places where time stands still in the name of heritage and tourism. To create a true portrait of the Celtic world would be an impossible task. Instead I have journeyed around its edges, looking in.”

This story was adapted from the National Geographic U.K. website.