'I needed to do something': How Indigenous people are building solidarity

Meet the activists, artists, and ordinary people who are finding ways to strengthen community bonds during the pandemic.

Activist Eryn Wise is living out of a camper van in New Mexico so she can organize the distribution of protective gear to pueblos and the Navajo Nation, where there have been more than 3,500 reported cases of COVID-19.

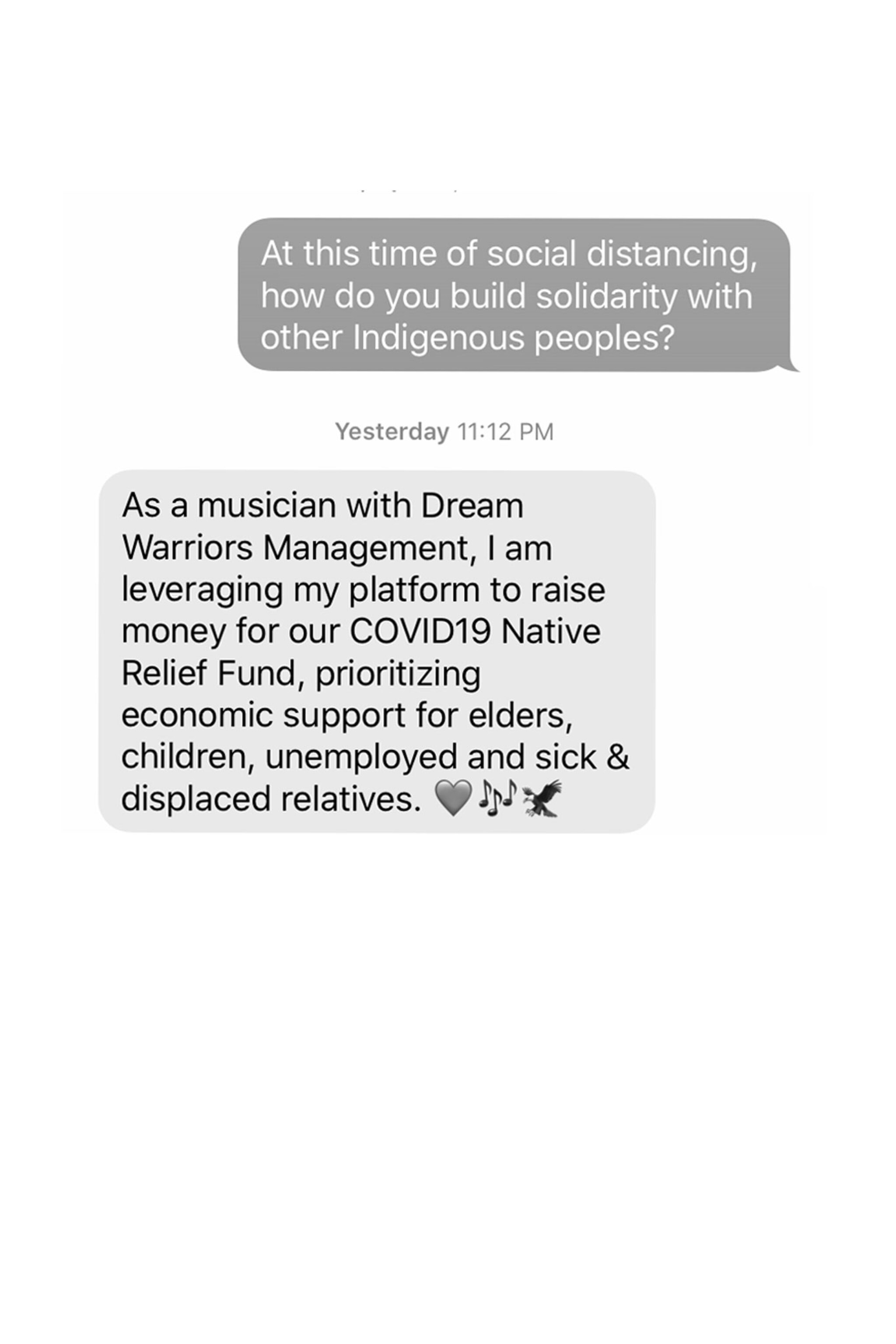

Lyla June, a performing artist and scholar, has distributed some 500 microgrants through her artists’ collective to indigenous people suffering from the coronavirus-related economic collapse.

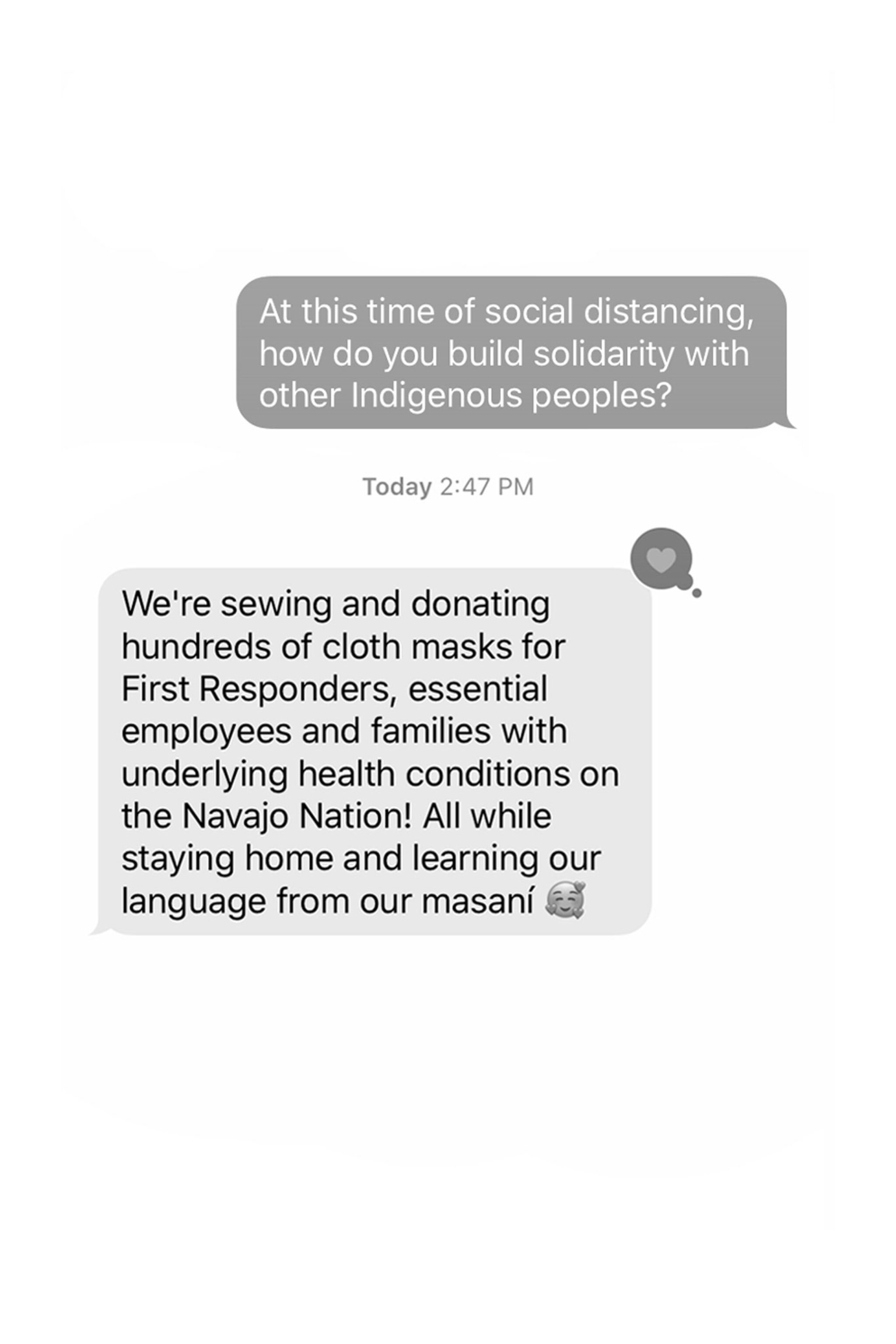

Carlesia Tully is making face masks. The stay-at-home mother made them for her sister, who is an EMT on the Navajo reservation, and her aunt, who is a nurse. Then she made masks for their co-workers. Then she went to the local store to buy diapers and realized that none of the workers had protective gear so she made masks for them. Then she made masks for the store’s customers, the post office employees, and the gas station attendants. “I lost count at like 1,700,” she says.

Wise, June, and Tully embody the idea of solidarity, a powerful force in indigenous communities. “It means being there for each other, taking care of one another, treating each other as kin,” says June, who is Diné (Navajo) and Tsétsêhéstâhese (Cheyenne). (Tully is Diné; Wise is Jicarilla Apache and Laguna Pueblo.) “It’s creating that sense of emotional connection and therefore a responsibility to help each other out.”

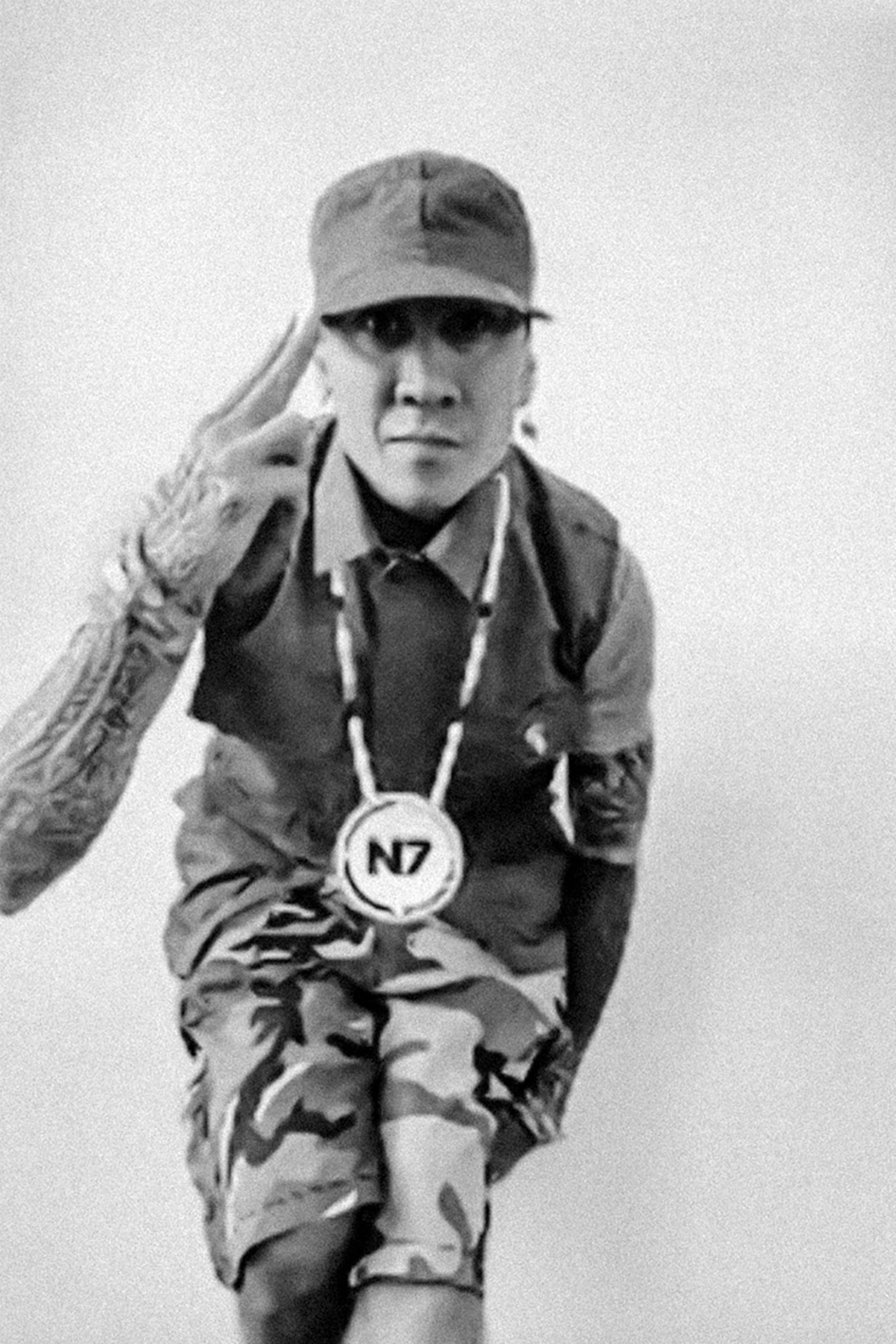

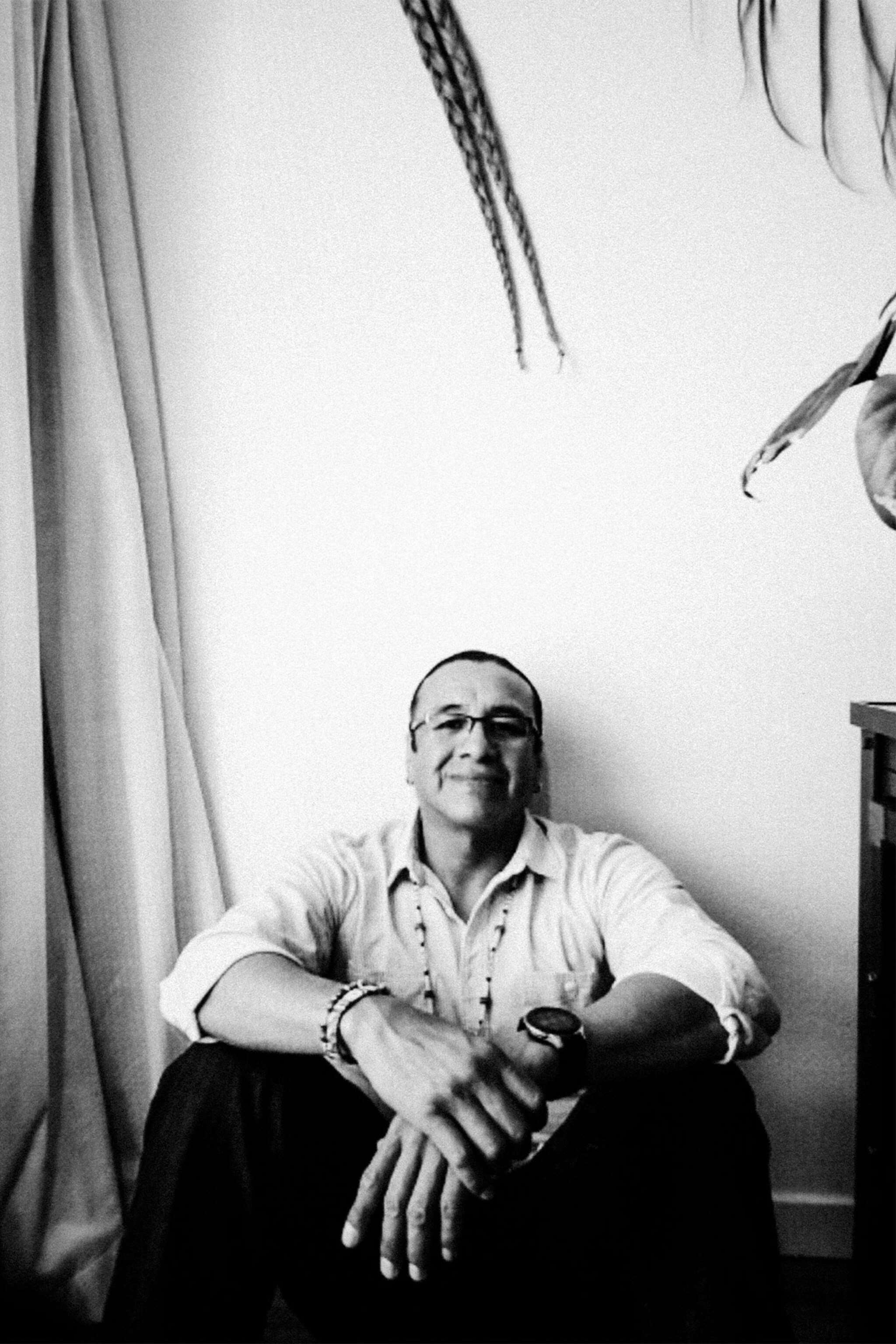

Photographer Josué Rivas made portraits of these women, among others, because he wanted to convey that sense of solidarity, especially during the pandemic.

Rivas had been having a difficult time at the beginning of the stay-at-home order in Portland, Oregon, where he lives. The news was dire, he didn’t know how he would do his work, and he dreaded what COVID-19 would do to the indigenous community. “I was in a bit of a panic, to be honest,” he says.

So he reached out to his elders for help. “That’s a thing that a lot of native people do,” says Rivas, who is Mexica and Otomi. “When there’s an unstable environment, you try to reach to those people that have taught you about ceremonies or traditional ways.”

One elder, his uncle, encouraged him to check in on indigenous people he knew. “That’s one of your medicines,” Rivas says his uncle told him. “You’re good at that.” Another, his friend Pualani Case, who is Hawaiian, reminded him that indigenous people practice solidarity.

That advice sparked an idea. He could make photographs during video calls with friends and people he respected.

The process “became almost like a ritual,” Rivas says. He photographed eight people—activists and artists, elders and musicians. He would talk with each person for an hour or so, and they would work together to make a portrait. Rather than photographer and subject, he says, they became collaborators.

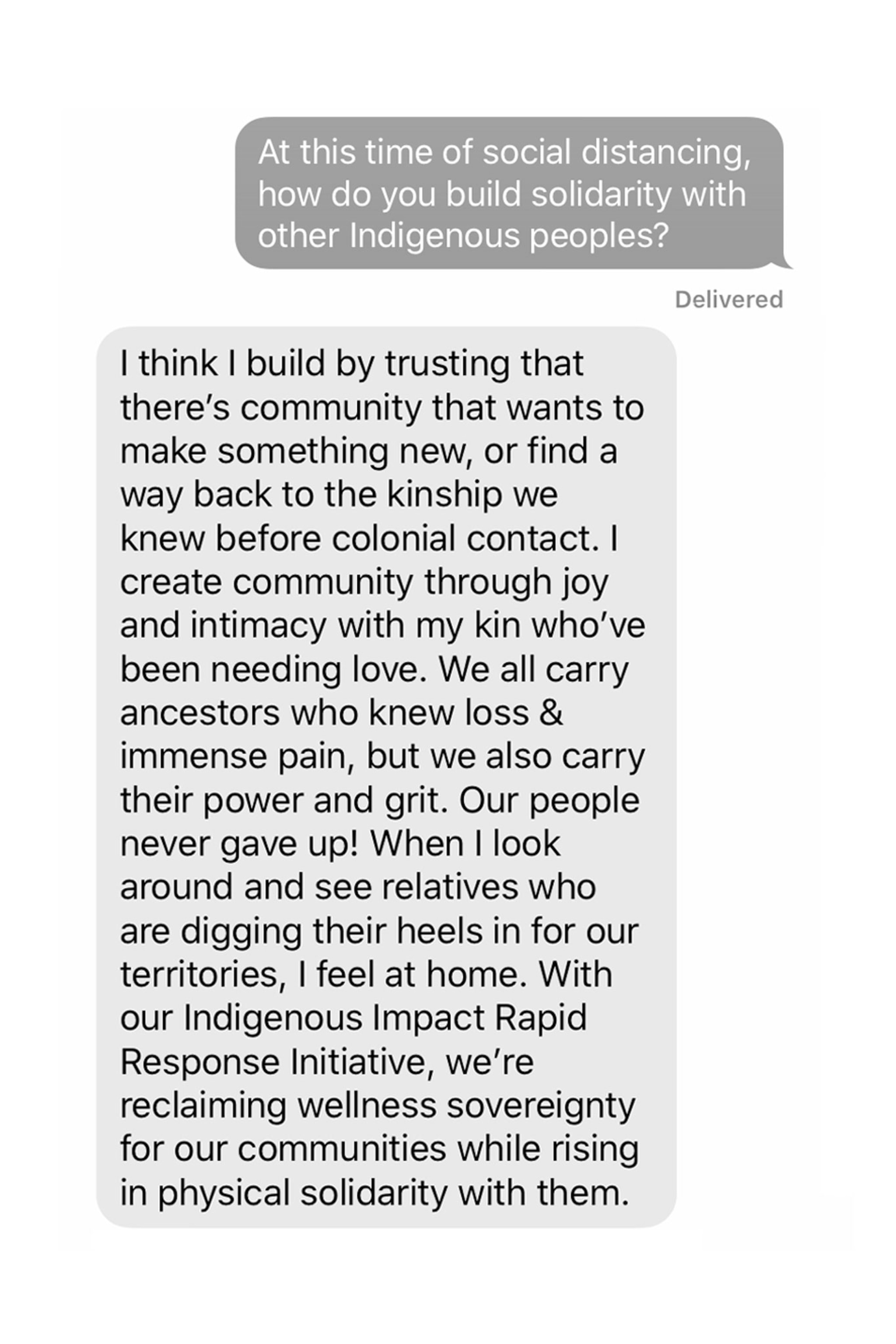

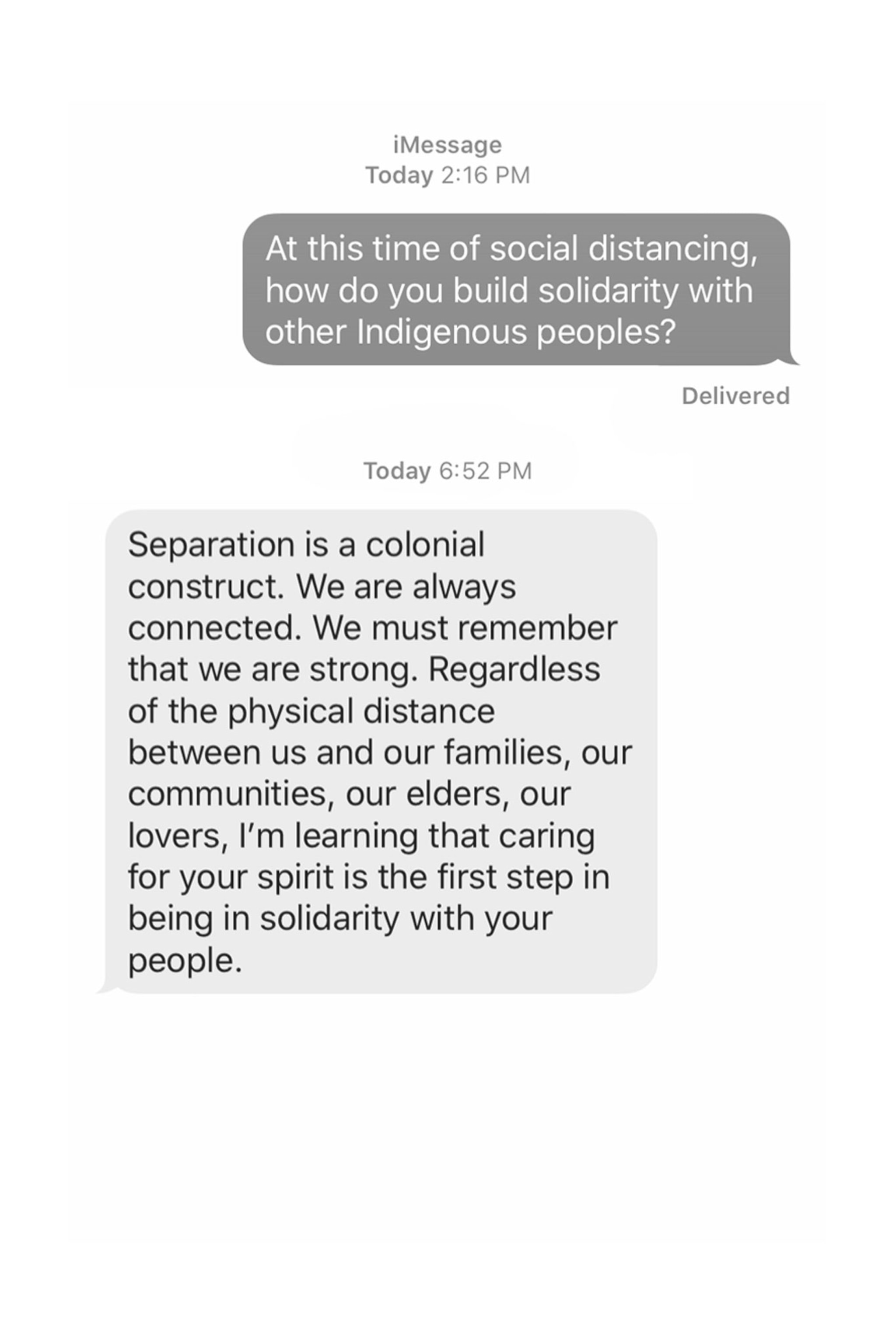

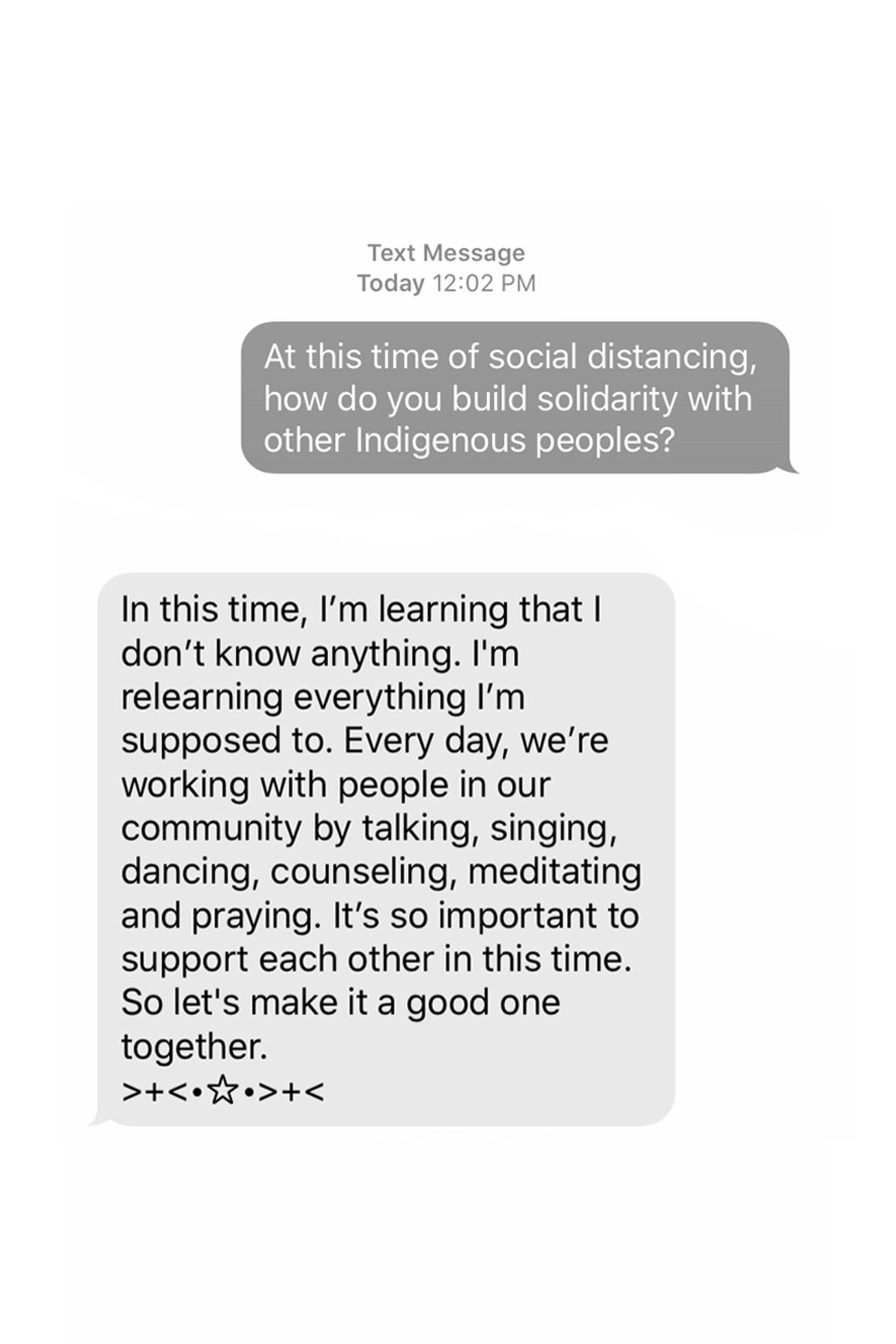

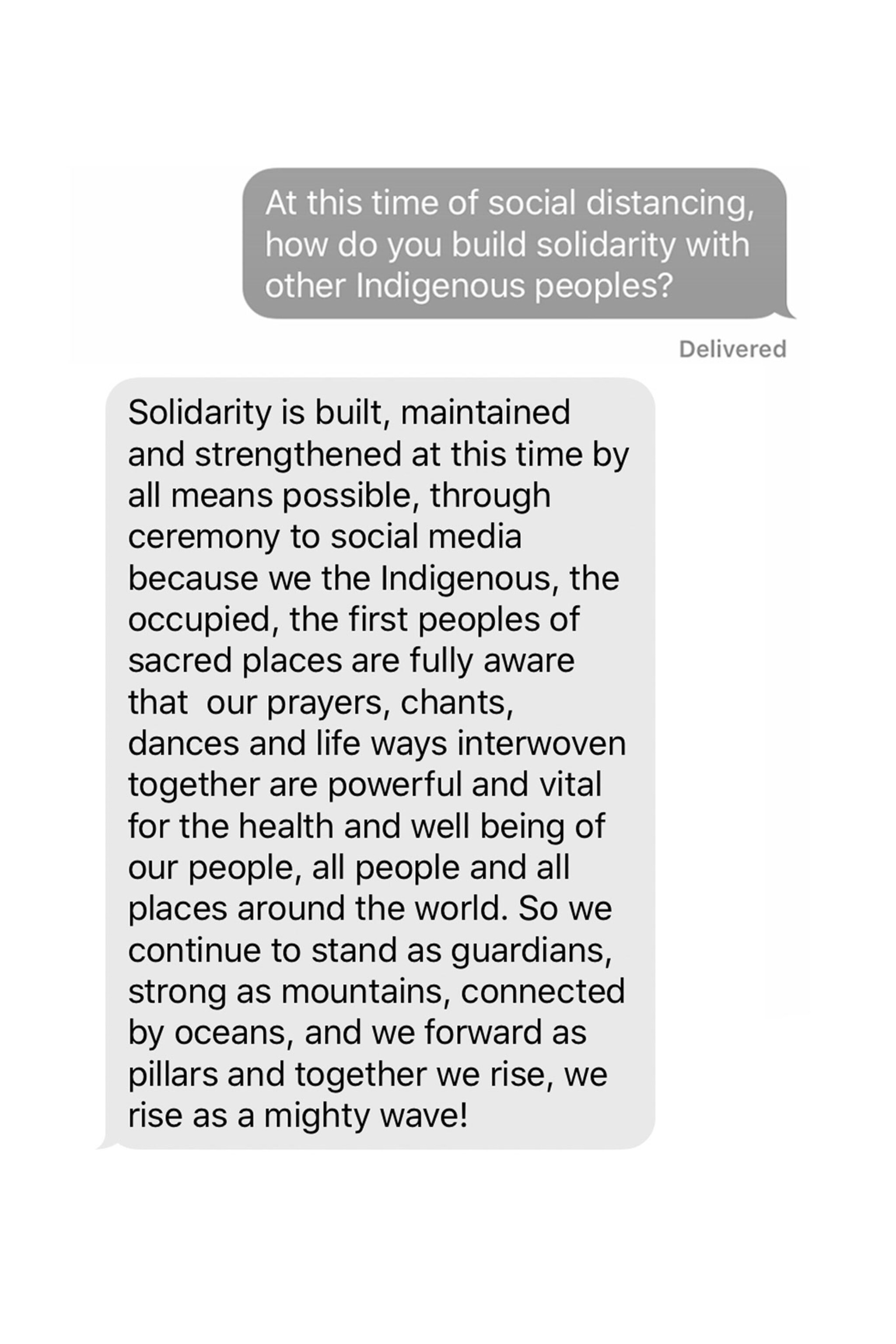

After the photo session, the conversation continued by text. “I wanted to really understand or even allow them to think of how they’re building solidarity right now,” says Rivas.

“Even for myself, I asked how am I going to show solidarity right now,” he says. His answer? “By doing what I know how to do best.”