Ice hockey is flourishing in ... Nairobi

There's only one rink in the country—and it's tiny—but the Kenya Ice Lions have their sights set on the Olympics.

Nairobi’s Panari Hotel sits alongside a highway between the city center and Jomo Kenyatta International Airport. On the second floor, across from a Chinese restaurant and next to a movie theater, is a small skating rink that serves as the home base for the Kenya Ice Lions, the only ice hockey team in equatorial Africa.

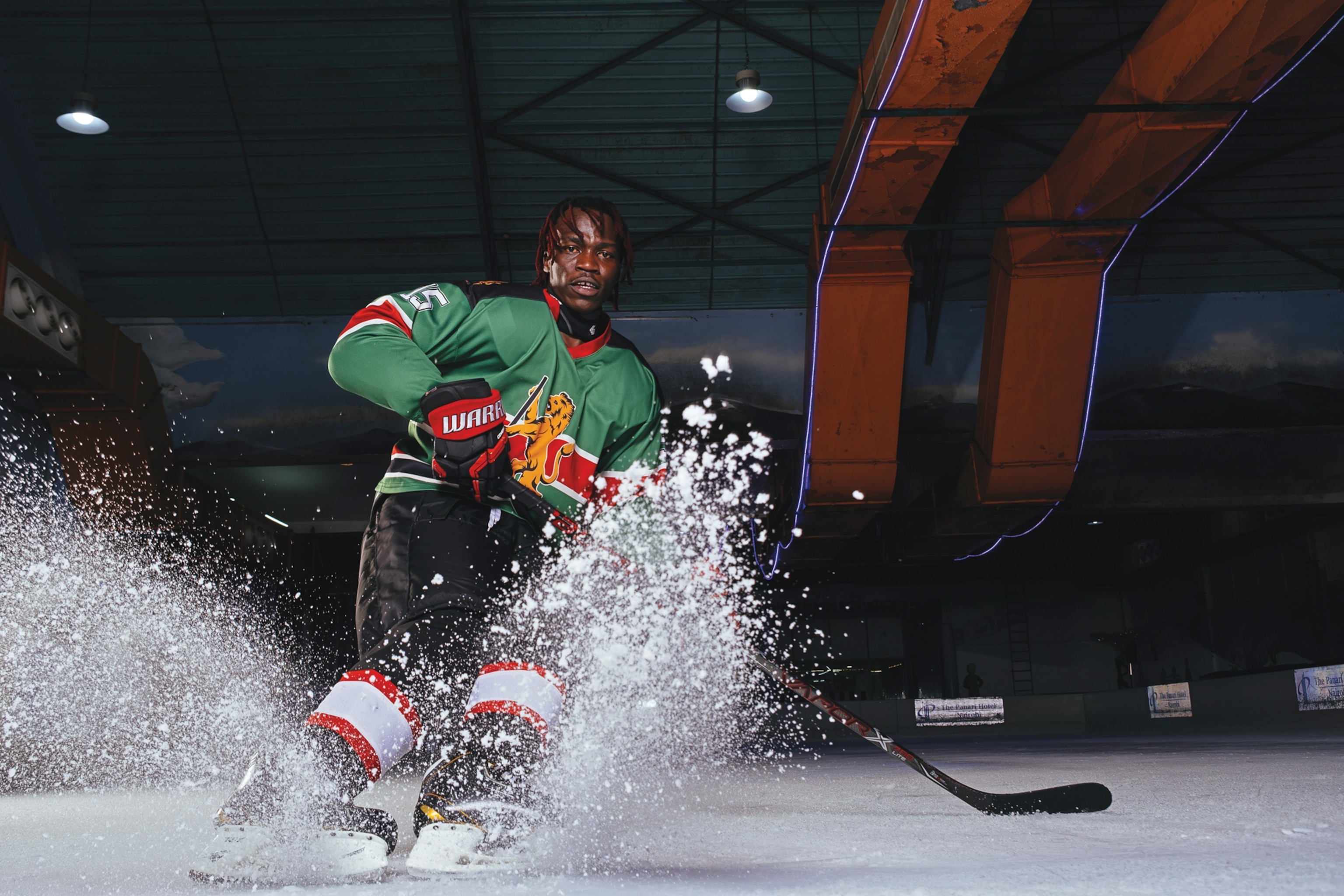

On a recent Wednesday, the arena echoed with the thud of hockey sticks and bodies colliding with the boards. From the bench, players shouted at their teammates in Swahili as they faced off in a five-a-side scrimmage on a rink just a quarter of the size of a regulation National Hockey League rink.

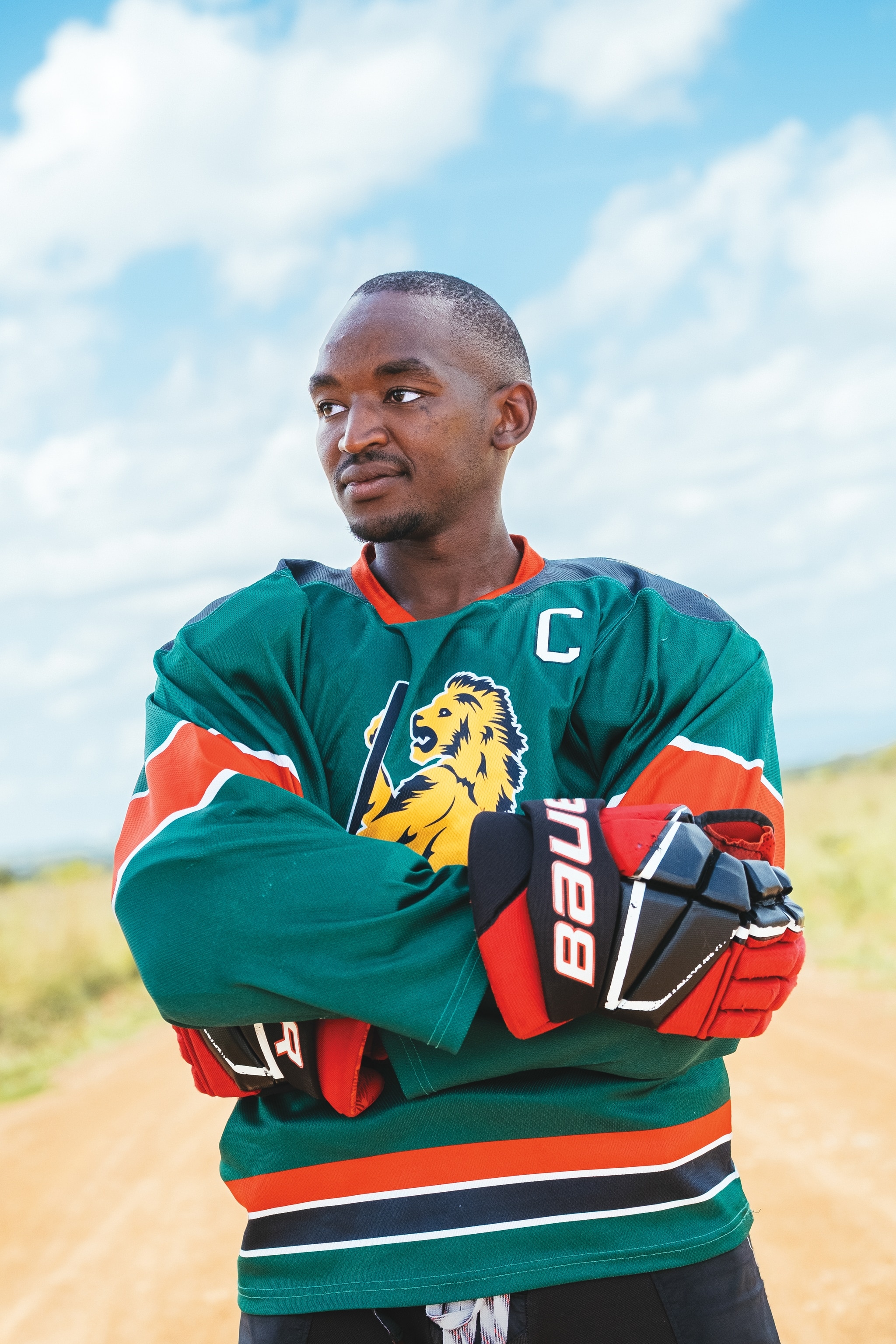

A vast divide exists in Kenya between the rich and poor, but here in Nairobi ice hockey is helping to bridge the gap. The team is made up of “people from very humble backgrounds, and people from the worldlier side of life,” says 30-year-old Ice Lions captain, Benjamin Mburu, who works as an architect and construction manager. Many of the team members are still students; some are unemployed. The sport has also been a lifeline for players like 21-year-old Chumbana Likiza Muhusini, who grew up in one of the city’s harshest slums. None of that matters on the ice. “No one cares about who came from where,” Mburu says.

Last year Kenya became the fifth African nation and just the second sub-Saharan nation to join the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF), the global professional body for the sport. It took nearly a decade for the Ice Lions to achieve that recognition.

The team began informally in 2016, when a few young Kenyans working at the rink as skating instructors grew tired of just watching Western expats play hockey and decided to give it a go themselves. Soon they were recruiting players from Nairobi’s rollerblading community, sourcing jerseys and other apparel from the city’s secondhand markets, and donning a patchwork of donated gear. “It was super cold, and I couldn’t control my skates,” Mburu says. “As an African, the closest I ever came to ice hockey was mostly Christmas movies on TV.”

It wasn’t long before the feel-good story of hockey on the Equator started to spread. In 2018, an executive at the Chinese multinational company Alibaba learned about the team through Facebook and flew some of the players to South Africa to film a television ad featuring the tagline “Ice hockey in Kenya? No dream is too big.”

The TV spot raised the team’s profile, but the Ice Lions still had no one to play against—until, later that same year, Canadian restaurant chain Tim Hortons flew the squad to Canada for training and filmed a documentary in which the players received full sets of gear and Kenyan jerseys, met hockey legends Sidney Crosby and Nathan MacKinnon, and competed against a Canadian team. For some of the Kenyans, it was their first time leaving Africa.

The players came home determined to build up Kenya’s hockey ecosystem. Today, retired Canadian pro Saroya Tinker is helping the Ice Lions launch a women’s league. And the team has begun a Saturday youth clinic to develop a pipeline of talent for future generations. Currently, as many as 70 kids show up for weekend practices.

The squad is coached by Canadian Tim Colby, who spent 10 years at the helm of minor league hockey teams in Ottawa before he moved to Kenya. Unsurprisingly, Colby says the group’s greatest hurdle comes down to the cost of ice time in Nairobi: At $100 an hour, it’s too expensive. And the rink is too small. On top of that, the Ice Lions—both players and staff—are all volunteers, and it’s tough to run a full-time, professional sports team on a volunteer basis, Colby says.

Despite these challenges, the Ice Lions hope to take part in the first ever African Nations Cup, tentatively scheduled for next June in Cape Town, South Africa. And they plan to work their way up through the many-tiered IIHF World Championship divisions, with the goal of eventually qualifying for the Olympics. “Nothing is impossible,” says Mburu.

Neha Wadekar divides her time between London and Nairobi, where she reported this story. She’s also written for the New Yorker, the New York Times, and the Economist, and her reporting on jihadi insurgency in Mozambique earned the Pulitzer Center’s Breakthrough Journalism Award.