Justyna Mielnikiewicz’s Woman With a Monkey

“In the far corner of the club I saw a woman with a monkey. She was strikingly beautiful … deep in her thoughts … holding the monkey as if it were her child. Was she a performer from a long-closed circus, a desperate mother trying to feed her family or someone displaced by war?”—Justyna Mielnikiewicz, excerpted from Woman With a Monkey

While rummaging through a flea market in California in the late 1990’s, Polish photographer Justyna Mielnikiewicz found a copy of Sebastiao Salgado’s book Other Americas, “somewhere between a mirror, a pair of old shoes, and a picture of Our Lady of Guadalupe,” she reminisced over lunch in a quiet garden in Tbilisi, Georgia earlier this summer. His book, a seven year visual exploration through Central and South America, served as inspiration for Mielnikiewicz to begin a decade-long project which has culminated in Woman with a Monkey, a collection of stories and photographs from the southern Caucasus.

Not long after finding Salgado’s book, Mielnikiewicz left her native Poland and her job at a daily newspaper, planning to pursue her own projects. Living in Tbilisi since then, she feels connected to the story she is photographing. This was especially true during Georgia’s war with Russia in the summer of 2008. It was the first time she covered conflict, and from that experience she learned about human nature and how easy it is to divide people. “The war doesn’t disappear—it reflects back on life many years after. “There is a part of society living in the past. Any country that cannot address its own civil war cannot move on,” which is why conflicts recur in the Caucasus, surmises Mielnikiewicz. “Civil war is not only what strangers do—it is also when neighbors start to fight each other. We pick up the guns. We make history with our own hands.”

“Life here for me is a voyage to extremes, where even a simple taxi ride can turn out to be a trip down Alice’s rabbit hole.”

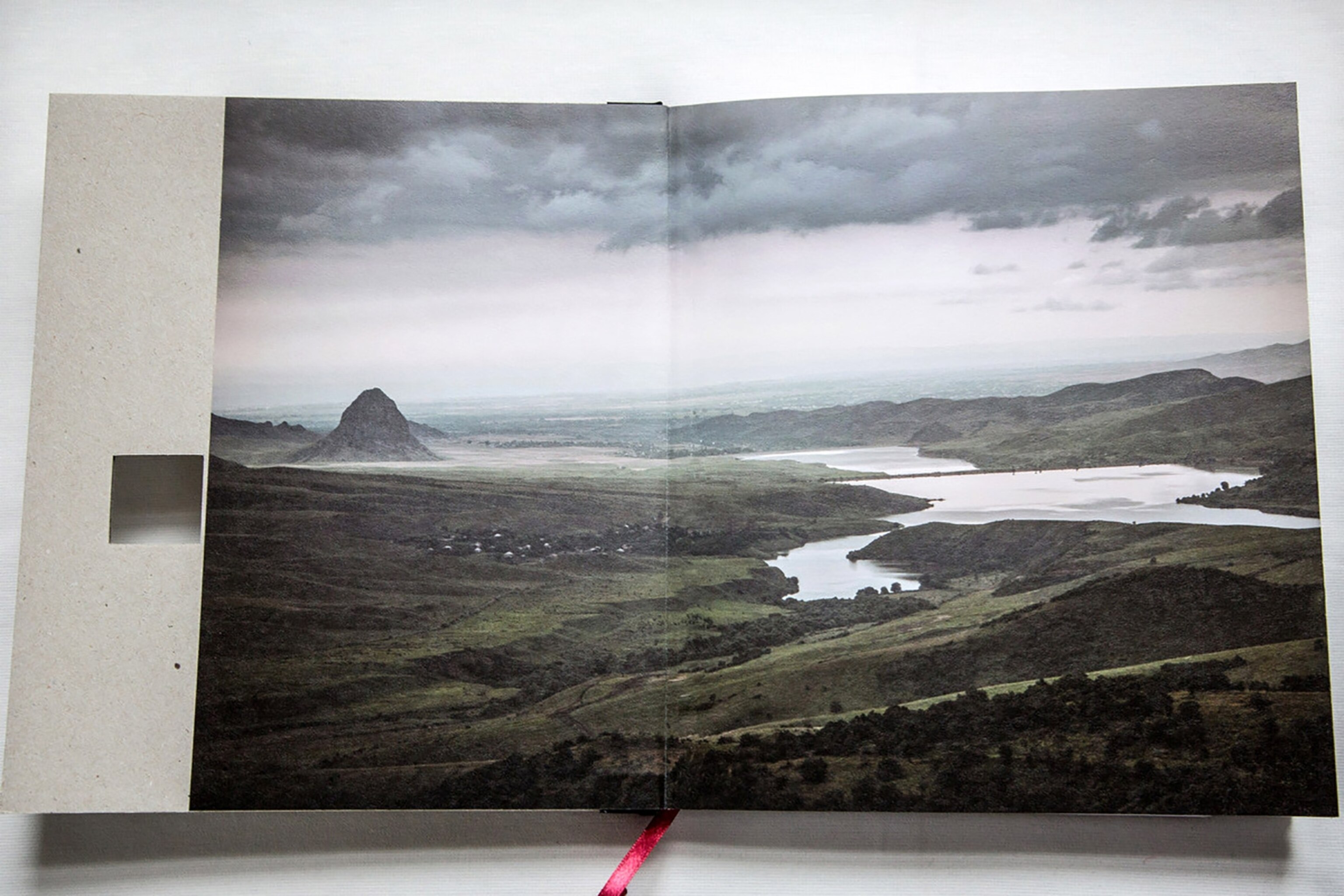

The southern Caucasus is known for its vibrant ethnic culture and dramatic history, and it is where Mielnikiewicz now lives with her American husband Paul Rimple, a writer, and their daughter Nestan. Self-taught, it was through books, like Salgados’s, that Mielnikiewicz developed a vision for how she sees and photographs the world.

“The Caucasus is all about history. Traveling through the region I have recognized how strongly politics are part of daily life and of how history often seems more important than the future.”

When asked why photographers are drawn to the southern Caucasus, Mielnikiewicz responds, “It’s because the people are more emotional, and life has greater intensity.” With a wry smile she adds, “It’s because of the altitude. In every country the craziest people come from the mountains, and here it is all mountains. There is a tendency to do first and think after.”

“Each party to the conflict distorts the historical narrative to justify their claims to land. … I have seen major historic events completely vanish from the chronology when they don’t fit into the current national agenda of defining the good guys from the bad guys.”

“My interest in trying to understand war and its long term effects on people has guided most of my work. I’m more curious about what motivated people to fight than in what they actually did. Civil war poisoned society completely, making lawlessness, self-destruction and brutality a part of daily life.”

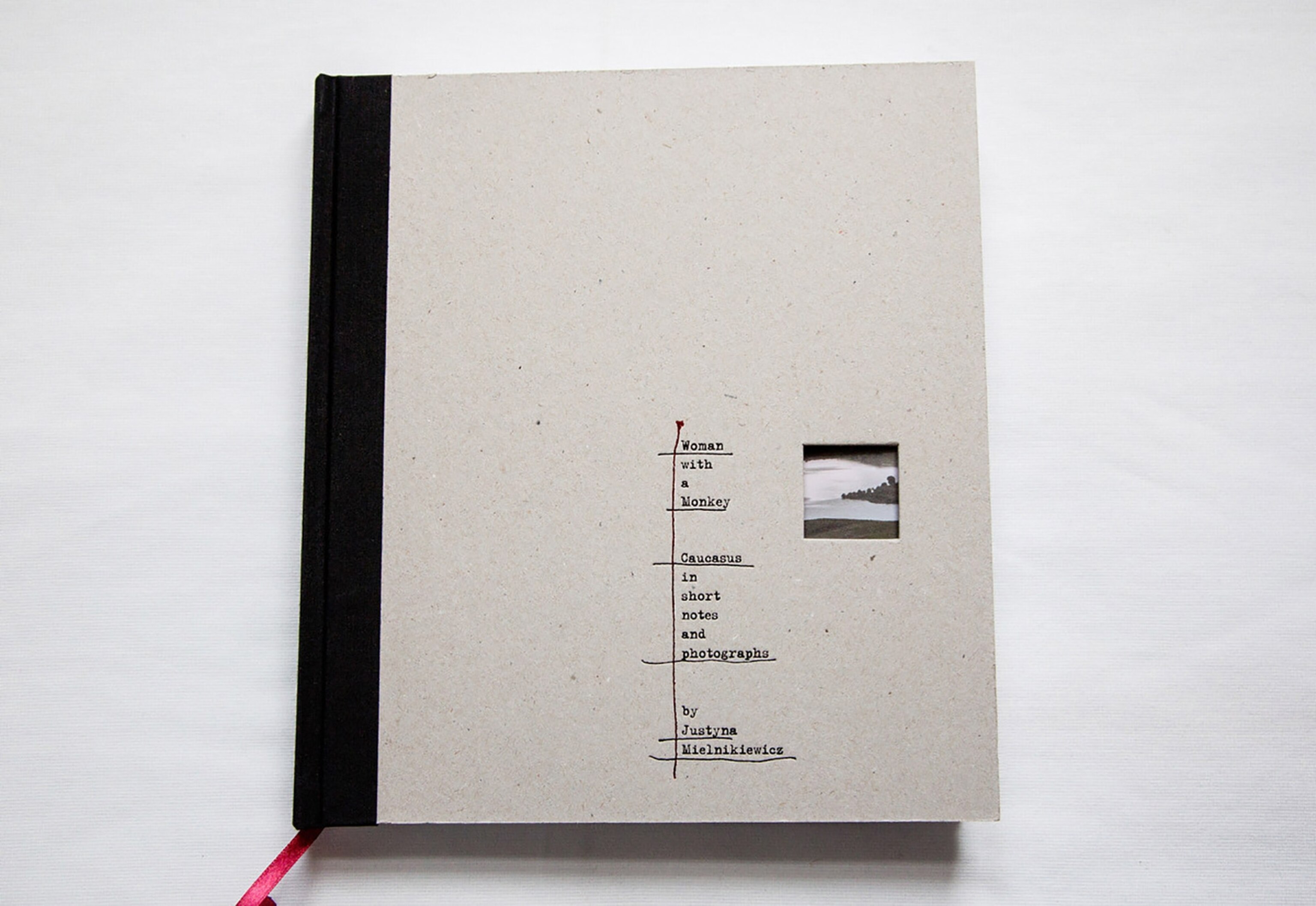

Much like the theatrical rhythm of life that Mielnikiewicz describes, the images in her beautifully crafted book follow a similar emotional pacing. Pictures of lovers and celebrations flow into scenes of loss and war, black and white moves seamlessly to color. Pages of thick paper stock unfold to reveal handwritten captions, and small texts written by Mielnikiewicz are scattered throughout. Longer stories written by her husband Paul appear as type-written entries—like a letter from an old friend.

Mielnikiewicz says she was looking for a structure and design that would make the viewer engage. She believes people spend time with it and move the parts around building their own narratives.

“Good photography is both dark and complex, but at the same time simple,” she asserts. “The first feeling is that you could jump in the hole and it could take you in.”

Mielnikiewicz is currently working on a project in the Ukraine examining how conflicting pro-Russian and pro-Western identities are shaping modern-day Ukrainian identity. See more of Mielnikiewicz’s work here.