‘I felt like the pandemic was being censored.’ Photographing life—and death—in COVID-19 Britain

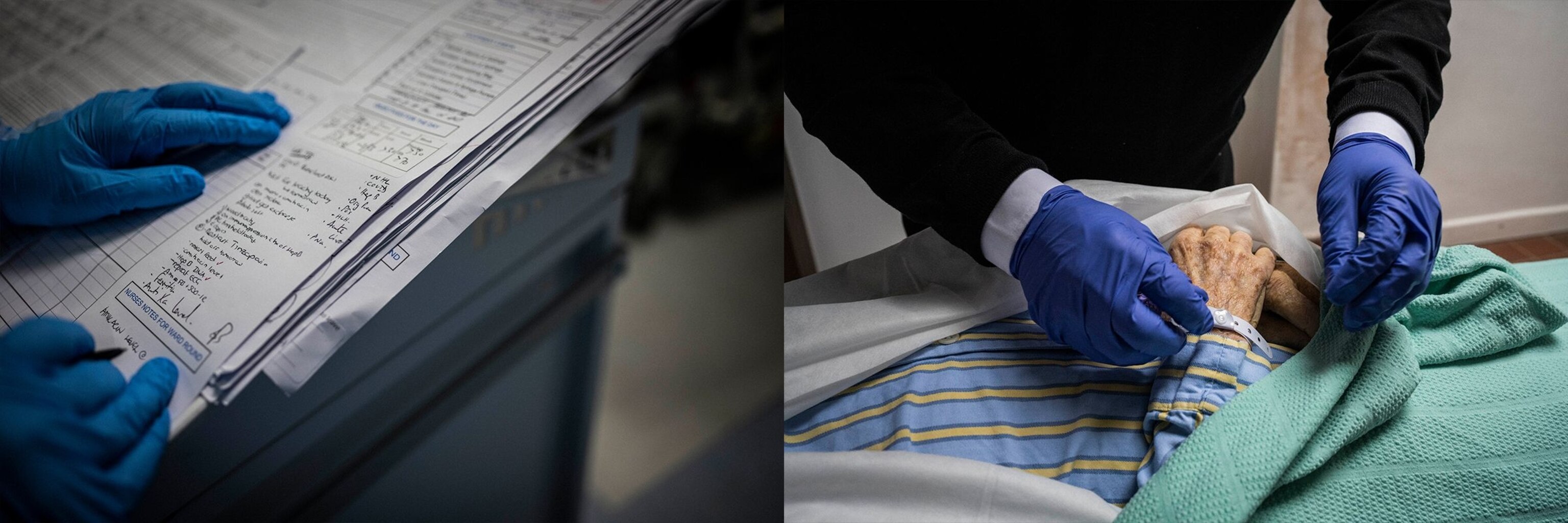

This photojournalist documented two little-seen front lines in the UK's war against coronavirus. Her images reveal intensive care of every kind—amidst a pandemic close to every home.

Lynsey Addario is a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist who has worked in over 70 countries and covered conflict and humanitarian catastrophe over a 20-year career. Born in Connecticut, she has lived in the U.K. since 2011.

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, Addario began to cover its effects from two sides of the fight: within the high-dependency wards of National Health Service (NHS) hospitals, and the funeral workers struggling to keep up with the number of dead arriving at their door. You can read her report here—and below, she describes photographing her first assignment on home soil.

I’ve never been confronted with a huge story unfolding where I live. All of my work has been overseas—and I’m usually the first on a plane to go off and cover some world event, or war. Once I was confident my family was in a good place and everyone was safe, I started thinking about how I could cover the pandemic.

It’s important for photographers, even if they’re not covering the ‘frontline’, that they are covering life right now. This is such a unique time, and we need a collection of images to look back upon. In villages, in cities, around the world - what did the pandemic look like?

On March 21, I wrote my first email to an NHS Hospital. I had been watching the many images of overwhelmed medical facilities coming out of Italy and the United States, but from the end of march to the beginning of May, I was seeing almost no still photographs of the COVID-19 wards in the United Kingdom. The statistics of high rates of infection and rising number of dead—coupled with NHS workers leaking stories of hospitals inundated across London and other major cities, and the lack of adequate PPE—spoke volumes. But, despite trying relentlessly for months to get into hospitals to cover the pandemic, I was repeatedly denied access. This was frustrating to me as a journalist. I felt like the pandemic was being censored here.

My go-to instinct is always suspicion. If you tell me as a photographer that I’m not allowed in to six different hospitals to cover a global pandemic, then I’m going to be suspicious about what is happening inside those hospitals. But there are so many unknowns with coronavirus. Obviously people are really nervous about journalists being in these wards and the intensive care units (ICUs)—and for good reason, in terms of the spread and the risk. Family and loved ones weren't being allowed in to hospitals and care homes to visit their gravely ill and dying, so it was on some level justified to keep all non-medical staff out. But documenting a crisis first-hand, witnessing success and shortcomings, is essential to inform policy, and hold leaders accountable. This felt largely absent to me.

(Related: 'It has become our sanctuary': The calming power of nature in a pandemic.)

If you want people to respect the lockdown, if you want people to understand just how bad it can be with coronavirus, they should see the images.Lynsey Addario

I do think there was some degree of the UK being unprepared for the pandemic. Not having enough PPE for the medical staff, for instance. And I think [the government] didn’t want the population to panic by seeing so many people infected with COVID-19. Which to me is counter-intuitive, because if you want people to respect the lockdown, if you want people to understand just how bad it can be with coronavirus, then they should see the images. So I kept asking and asking, and writing to all these different hospitals.

I wasn’t allowed in until it was very quiet. Most of the wards had emptied out. And the irony was, every single hospital I went in to, from end of May, the first question the medical staff asked was ‘where were you at the height of the pandemic? Why weren’t you here mid-April?’ They wanted the press to cover what was going on and what they were going through, how inundated they were. But very few people were granted access.

So much of my work over the years has been about being on the brink of death. The aftermath, the rituals, how different cultures approach not only tragedy and trauma, but also war and humanitarian crises. I’ve covered basically every war of the past 20 years, but I have not covered a global pandemic. And I had to learn very quickly.

The toughest thing about covering coronavirus is not knowing where the frontline is. Where the danger is. There are so many people who are asymptomatic. You don’t really know where you can catch it, who might be higher risk. So I just went into full-on preparation-for-war mode in the beginning, learning from doctors who specialized in infectious diseases about PPE requirements, how to don and doff gear, and what situations were higher risk compared to others.

It's always astonished me how doctors, nurses and healthcare workers really put themselves out there. They’re exhausted, it’s emotionally and physically draining— their lives are also at risk—but they’re always thinking about the patient. It’s incredible to see that.

I saw one nurse leaning over a patient. He couldn't speak because, like many of the other critical COVID-19 patients in the ICUs he was on a ventilator, and she was leaning in close and kind of reading his lips. I quickly took a photo and I said, ‘what were you saying to him?’ and she said: ‘I noticed he was a little down today and I just wanted to make sure he was OK.’ It was so beautiful because on top of everything else—on top of making sure that they have patients' medicines in order, that they have everything they need, keeping them clean, keeping everyone alive—they're caring for their emotional state.

What we all tell ourselves is, ‘we’re not the vulnerable ones. We’re young enough. It only hits people who are over X.’ But I think the reality is, there are the outliers. There are young and healthy people who are hit very very hard. The surprising thing in a few of the ICUs that I visited was that some people were young. They were 50, 51. To see the patients who are not much older than me—I'm 46—is scary. There are people who fall out of the categories that we’ve been told.

People asked me if it was hard to shoot through a visor. I’ve worn a burkha, a flack jacket, helmets—I’ve shot fully veiled when I met with the Taliban in 2008, I’ve shot in any kind of imaginable outfit you can think of. Is it comfortable? No! But it’s necessary, and if it helps keep me alive, and keep the patients safe from whatever I might have, that’s the important thing. It’s inconvenient and it’s hot—but the doctors have to spend all day, every day wearing that.

Most funeral homes had double the amount of deceased that they were handling normally. I started working with one that had 40 COVID positive, or suspected COVID positive, bodies in a garage – where they normally kept the hearses – because they were so inundated. Many places kept suspected and COVID bodies separate; but these were just an overflow of bodies because there were so many people dying, and funerals were taking so long to take place. There was a huge backlog.

Every single person I worked with was putting their life on the line. Funeral workers were dressing the deceased, people who died from COVID-19, doing embalmings. And it didn’t seem that there was any mention of the fundamental work that they were doing. They were providing a service to everyone who needed it. It's very important to cover these key workers who have put their lives at risk.

I photographed a pallbearer called Jake Kill, working at a funeral services at Surrey throughout the pandemic. One of his children was vulnerable, and quite young. So he stayed away from his family. He would see them socially distanced. There was a moment when his son made a drawing for him, and he broke down. He knew that as a key worker, as someone who was handling deceased people who had died of COVID-19 or with COVID-19, he had to be careful for his family. He would get tested regularly, and then he would isolate—and if the test came back negative, he would be able to hug his kids.

Access to this story in the UK has been some of the hardest I’ve tried to get in my career. From going to the hospitals to asking to photograph a funeral is really asking to access one of the most intimate moments in someone’s life—especially for a family in mourning. It’s tough and uncomfortable to ask, but there were families who understood the value of documenting this. Of looking back at it in 20 or 30 years and knowing what this period in time looked like. It's critical to be honest, transparent, and very clear about what I’m working on and why I think it’s necessary to tell a particular story. Then people make their own decisions whether they want to be involved or not.

The U.K. is so diverse. And I think whether you’re Buddhist or Hindu or Muslim or Catholic, it’s important to show the different traditions that come along with burial and death. There was a Buddhist teacher, Rob Burbea, who passed away from pancreatic cancer. He didn't want to be in a hospital or hospice during coronavirus because of the increased risk of exposure to others, and because his loved ones wouldn't be able to visit. He made the decision to pass away gently in his own home; he was cared for by six women who tended to his every need in the months leading up to his death. They did what a hospice worker would have done, with no previous experience. After he passed away, they held an online vigil via Zoom, where around 300 people came and sat silently with his body, remotely. And then before delivering Rob to the undertakers in Devon, his caregivers meditated and chanted over him at dusk by candlelight. This sort of beautiful care only with friends probably wouldn't have happened before coronavirus. The world slowed down, and had become more intimate within peoples’ respective bubbles.

In the U.K. I’ve found people are really, really stoic in terms of their emotions. I’m used to working in countries where people are throwing themselves at the grave, throwing their hands in the air crying—being very expressly emotional. And here it was hard, because people are very contained. And it’s hard to show sadness if you don’t see it, especially with a still photo.

Zoom has played a part in so many funerals. Everyone now has a phone up, to either the casket or the body of the deceased to show relatives and loved ones who can’t make it. That is really unique, and something I’ve never seen before the pandemic. It seems like every funeral I go to now is being Zoomed.

What ties these two bodies of work together is the proximity to death—and death itself. And, I think, people’s approach to the family members, the workers, the people affected from these deaths.

This is a terrifying virus. There’s a degree of complacency amongst young and fit people because they think, well, it’s not going to hit me. But that’s proving not the case all the time. To see someone being kept alive on an ECMO (Extra Corporeal Membrane Oxygenation) machine, their body completely ravaged by COVID-19, it’s terrifying. I attended the funeral of a paramedic named Peter Hart. There were dozens if not hundreds of people on the hospital lawn when I was following the hearse. And I saw his photograph taped to the back and I just thought, ‘my god—he was so young.’

There are a lot of things that seem to have changed forever in the lockdown. I’ve seen that people have really learned to appreciate the freedom that we had that we now may never get back. Freedom in terms of socialising, in terms of how we shop, how we have funerals. Having dozens of people crammed into an office, or thousands in a high rise. These things may never go back to normal.

Tragically, what I’ve been covering for 20 years, is life and death. It’s not something I’m unfamiliar with. But like with every story I’ve done I’ve found myself crying sometimes, or really sort of entering these beautiful moments of celebration of a life that ended too soon. There were funerals where I was crying really hard for people I never knew and had no connection to. But you can’t help as a human being to feel other people’s emotions when you are that close to them, and documenting them. At least, I can’t.

This work was supported in part by the National Geographic Society's COVID-19 Emergency Fund for Journalists.

This article was adapted from the National Geographic U.K. website.