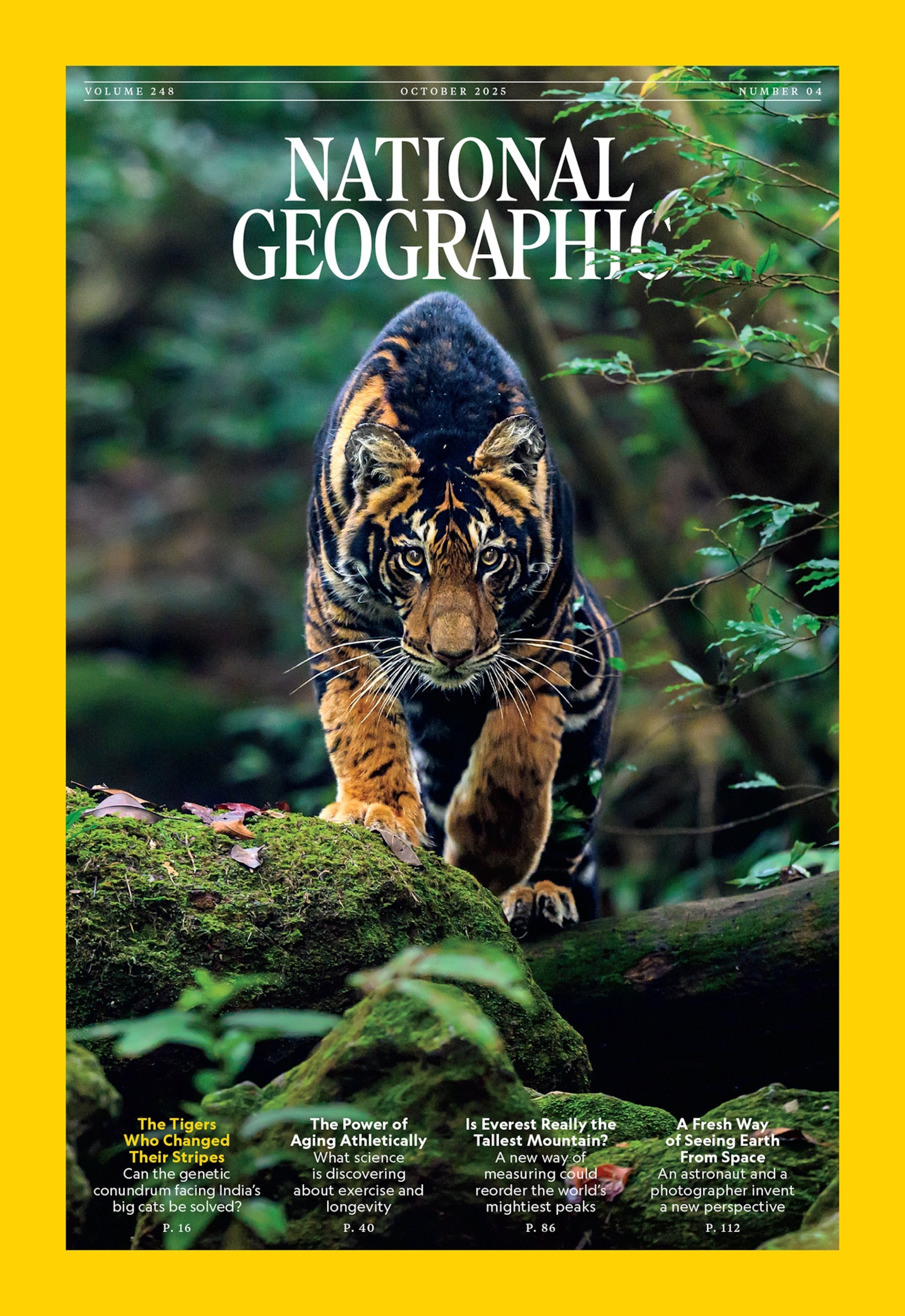

Tracking a rare tiger for 120 days to get the perfect cover shot

Prasenjeet Yadav had one goal: capture the perfect image of a pseudo-melanistic tiger for his story on India’s Similipal Tiger Reserve. Easier said than done.

Similipal Tiger Reserve is not like the dozens of other protected big cat areas in India. Isolated from the wider reserve system, roughly half of Similipal’s tigers carry a genetic mutation known as pseudo-melanism, which widens their black stripes. Given the vastness of the reserve, it's extremely rare to see them in the wild—and even rarer to create a magazine-worthy image of them. National Geographic Explorer and photographer Prasenjeet Yadav spent 120 days studying, tracking, and eventually photographing Similipal's unique tigers—all while working with a team of genetic experts and forest officials to unravel the mystery of how the tigers changed their stripes—for National Geographic’s October cover story. In our interviews with him below, he takes us behind the scenes and shares how he got his dream cover shot.

(Read more about the curious case of the tigers who changed their stripes.)

We know you've been obsessed with tigers for years, but what's the deal with the ones in this story? They look a little different than usual.

Yadav was a molecular biologist before becoming a photographer, and was a researcher in molecular ecologist Uma Ramakrishnan’s lab in India’s National Centre for Biological Sciences when he first heard about the black tigers. He left her lab to pursue wildlife photography and filmmaking, but when he later learned that Ramakrishnan—a National Geographic Explorer—and her team had figured out what made the tigers black, he said he knew he had to tell this story: “I never saw stories as just stories … I also build them with data backed from active research.”

So when it came time to tell that story, how did you actually go about photographing these black tigers?

The challenge that Yadav is describing was unique to black tigers. He notes that, interestingly, tigers are “generally not very camera shy. They’re usually more curious than scared.” But the black tigers were staying away from his camera traps because they were more skittish and could smell human presence.

Fortunately, his previous experience photographing snow leopards for an earlier National Geographic assignment came in handy. Like the snow leopards, the tigers of Similipal were highly sensitive to changes in their environment. So Yadav strategically altered his camera-trap methods: “What I started doing is hiding those cameras and leaving one camera on the trail, but at the same time adding another camera at [an] unexpected place every time. So a tiger would move on that trail once in 15 or 18 days—and it was a long trail—and I would, every time the tiger would pass from there, I would change the locations of the cameras.”

All great National Geographic stories take teamwork to come to life. As you look back on your time working on this project, who really went above and beyond to make sure you were able to do such great work in Similipal?

“I am the one in the field taking the photos, but it's not a one-person job,” says Yadav. “I had a big team to start with … The most important was the local field team, like Raghu Purti, who is [a] man of a few words but extremely sharp about the forest. I think we both learned a lot from each other—me more from him, because he knew the forest better than anyone ... The Odisha forest department and forest officers became kind of partners beyond just giving access. They helped me with logistics, they helped me with their existing knowledge of where these tigers are found, where they move. Researchers from Wildlife Institute of India played a vital role in helping me to get this picture, sharing their existing knowledge about Similipal. And National Geographic’s photo engineer Tom [O'Brien] helped me build all these [camera-trap] systems.”

Spending long weeks in the field tracking the tigers required a lot of waiting and patience from Yadav and his team. They also had lighter moments while listening to the wildlife calls:

“We would just constantly keep playing these games of, oh, what is this sound? And one evening we actually heard the tiger call when I was setting up a camera and I remember Raghu look[ing] at me and be[ing] like, tell me what this sound is. And I'm like, dude, this is a tiger, of course! And he was just playing along with me, and then we ran to the car.”

You were in the field on and off for a year. How long did it take to get your first camera-trap photo of the tiger?

Witness the moment Yadav reviewed his camera-trap footage and finally found his camera traps had captured a good photo of a black tiger:

But this still wasn’t the first direct-sighting photo you wanted, right? When did you get that?

Yadav carried his Nikon Z 9 camera with a 400mm f2.8mm lens each day for almost 120 days, just in case he spotted one in the park. It finally paid off. Experience that moment in this video:

And that groundbreaking photo ended up becoming your first ever cover for National Geographic! How does that feel?

“I mean, this is where I don't have many words,” Yadav says. “Here was a hook in my mouth wanting to get a cover story and if I wouldn't have gotten this one, I would've spent another 10 years trying to get it.”

“From the story point of view, I'm genuinely happy … because this story deserves that kind of attention.” He adds, “at no point I ever thought that I would get [the] photo that we have. I had a photo in my mind, but the one that we got on the [second to last] day was way better than the one that I ever imagined. I know I'm not very spiritual, but that day I felt extremely spiritual. I was like, this is Similipal’s blessing to me. It has seen me work hard for [the] last 120 days and this is how it is saying goodbye to me.”