Poetic and Surreal, Photos Show a Country in Flux

Photographer Emine Gozde Sevim turns a cinematic eye on conflict and change in her native Turkey.

The night of May 27, 2013, photographer Emine Gozde Sevim was staying with family in her hometown of Istanbul, Turkey, when she saw friends posting images on their Facebook pages from Gezi Park. A group of activists had gathered to protest a redevelopment plan that would destroy one of the city's last remaining green spaces, replacing it in part with a shopping mall.

She grabbed her camera and headed over.

Sevim was in her late twenties then, and the Turkey she had grown up in was, she says, one of authoritarian rule and subdued voices. She had sensed the energy building up over time. By the time the destruction plans for Gezi Park were being executed, much had already happened around issues of individual rights, including abortion, how many children women should have, and restrictions on alcohol consumption. "So though Gezi was the last piece of nature left in the center of the city—and this mattered—its significance was really the order of events that had preceded the protests there," she says. "One could even argue that only after the protests did some people learn the name of the park—or that that's when the park truly became a community space."

No one was expecting the populist upswell to grow, culminating several days later in a violent governmental crackdown. Though the momentum of those days didn't result in any institutional change, Sevim says, people uniting in protest against a common cause came close to a vision of what things could be like when the walls of social, economic, and ethnic prejudice are broken down.

"It was so beautiful," she says of the scene that first night. "There were so many different types of people—young people, old people, famous people, children, all types of Turks and Kurds," from different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. "That night in Gezi, people felt so creative. It was really romantic in that sense. People were very innocent."

While an outside perception may be that Turkey is an example of East and West coming together, a functioning democracy as well as a functioning Muslim country, "Turkey is not harmony," Sevim says. For one, ethnic tensions between Turks, Kurds, Arabs, and Armenians make the situation much more complex. But Gezi "opened discussion about why all of us should be here—conversation[s] about equality. To see that you can just ask questions and not get beaten up, that is a luxury."

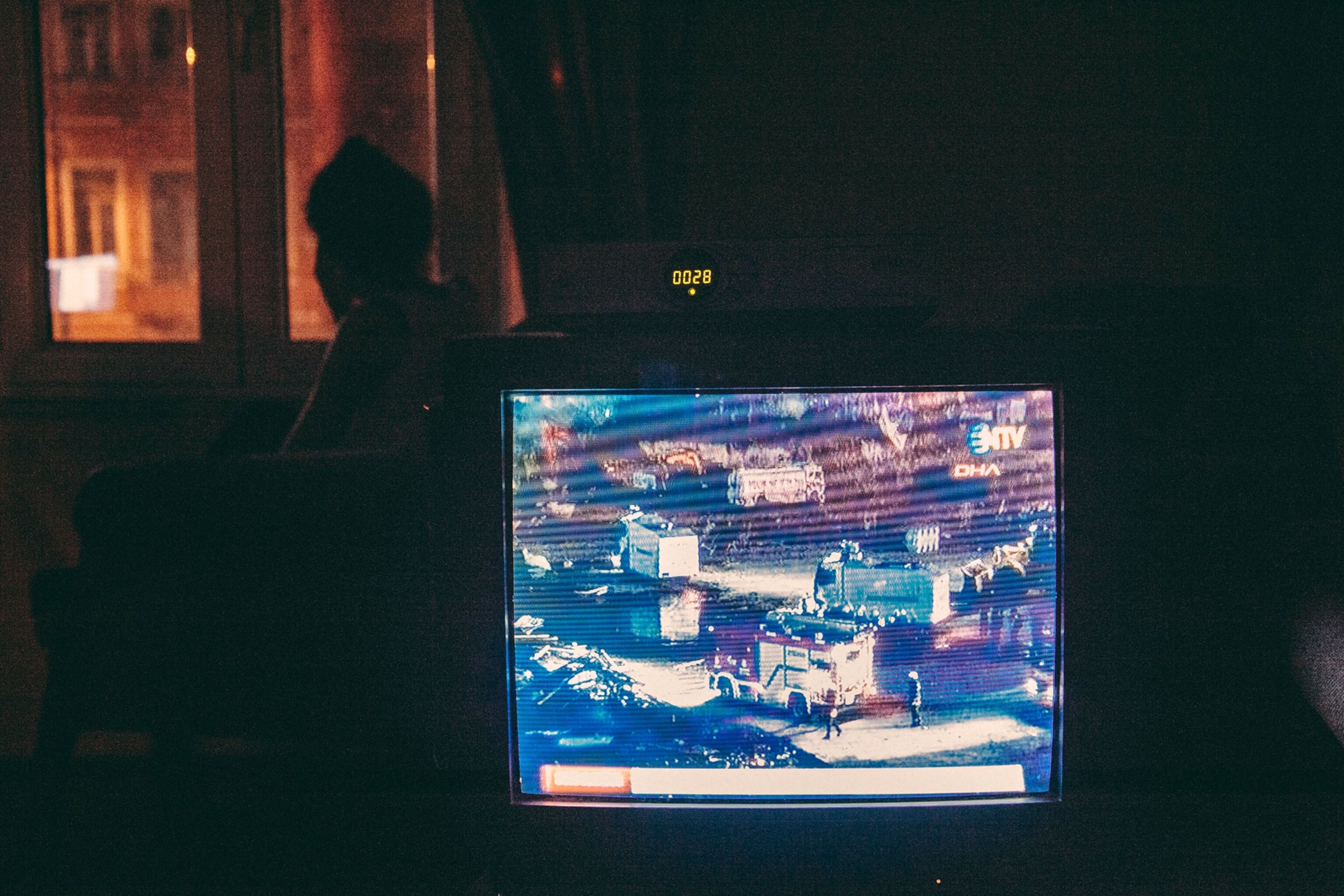

The photographs of the protest and the days leading up to, and after, it became part of a project she calls "Homeland Delirium." The images are meant to describe the mood of the time rather than be a linear narrative of events. Her personal involvement and investment in the future of her homeland lend a nuance to her images that is wholly unique. They speak of hope confronted by darkly complex realities.

"Some of us happen to be connected to history in a very personal way," she says. "Historic moments unfold, and I am trying to find my place in that unfolding. Nobody should care about that one individual person, but then there's that personal narrative that brings everything home."

Her experiential style has led to questions of whether the photographs she makes are photojournalism or art, categorizations she wholeheartedly resists. She has never had a formal assignment, she says, though her more straightforward documentary images have been published by news outlets. She photographs scenes as she finds them, though the freedom of working on her own allows her to follow her instincts. She is more influenced by cinema than by still photography, she says, as this format comes closer to the surreality of the scenes she's witnessing.

The work won her a Magnum Emergency Fund Grant in 2015, which she has used to continue exploring the socio-ethnic fabric of Turkey. She spent part of last year in the southeastern part of the country near the Syrian border. And she covered elections where a party born out of the Kurdish political movement gained entry into parliament, leading to a renewed sense of hope for Kurdish rights and a rethinking of racial and political attitudes in Turkey.

Sevim also witnessed that flash of hope be extinguished as the area became a volatile entry point for refugees and ISIS fighters crossing into Turkey from Syria, as well as an exit point for Kurds leaving to fight ISIS in Syria. She plans to continue exploring the complex threads of her country, even as she fears an outcome where the country becomes further drawn into conflict.

"At the end of the day I'm just a citizen with a camera," she says. "I am not trying to tell people what the reality is. I don't care for framing the perfect picture because I don't believe in such things. If I can make people feel ... then I am doing something right."

See more of Sevim's photographs on her website.